July 8, 2016

Air Date: July 8, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

CA Nukes To Shut Down; NY Nukes Troubled

View the page for this story

PG&E has decided to take the aging Diablo Canyon nuclear plant near an earthquake fault in California offline by 2025 and replace its electric power with wind and solar. But the even older Indian Point reactors near New York City continue in service despite defects and opposition. The President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research, Arjun Makhijani, joins host Steve Curwood to discuss nuclear energy and its future. (08:00)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood and Peter Dykstra celebrate the healing of the ozone hole, discuss the short-term extension of the herbicide glyphosate’s license in Europe, and look back on the arrival of the devastating chestnut blight in the US. (04:30)

Squash Bee: The Pollinator That Follows Farmers

View the page for this story

Thousands of species pollinate our plants and guarantee our food, but one particular bee specializes in the squash family. As ancestral farmers spread the cultivation of squashes through the Americas, the squash bee followed. North Carolina State biologist Margarita Lopez-Uribe explains the history to host Steve Curwood. (08:05)

Gardeners Create a Bountiful Backyard and Find Love

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

With nurturing, even a degraded backyard can yield a delicious bounty of produce -- and maybe even true love. In their book, Paradise Lot, gardeners Eric Toensmeier and Jonathan Bates tell their personal stories of finding romance and growing a food forest of perennial plants. We revisit a story by Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb who visited the gardeners in Holyoke, MA to sample their harvest. (12:30)

Finding New Tyrannosaurs

View the page for this story

Sixty-five million years ago, T. Rex was the biggest carnivore on Earth, and to this day it looms large in our imaginations. But science now knows this iconic tyrant lizard was but one of more than two dozen species of tyrannosaur, a diverse family that lasted 100 million years and came in many shapes and sizes. David Hone, author of The Tyrannosaur Chronicles, tells host Steve Curwood what we know about these extraordinary creatures and why he thinks even more species will be unearthed. (14:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Arjun Makhijani, Margarita Lopez-Uribe, David Hone

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Birds, bees and butterflies aren’t just pretty. They pollinate many of the plants that feed us.

LOPEZ-URIBE: Squash, pumpkin, zucchini are actually all pollinated by this squash bee. And this bee expanded its range dramatically thanks to the cultivation of crops outside of the native range of the plants that are not domesticated.

CURWOOD: How Native American farmers helped spread the squash bee. Also, how permaculture can transform an ordinary suburban backyard into a cornucopia of delicious food.

TONSMEIER: We have blueberries and serviceberries, and raspberries, and hazelnuts, and grapes, and rhubarb, and strawberries, so in just this tiny corner, we have all those different plants fruiting and producing excellent food for us.

CURWOOD: That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

CA Nukes To Shut Down; NY Nukes Troubled

Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant in San Luis Obispo County, California, is situated near a fault line (Photo: marya, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The Diablo canyon nuclear power station in California that was built in an earthquake zone thirty years ago is now scheduled to shut down by 2025 with the power replaced by wind and solar. But the operators of a troubled reactor at the even older Indian Point plant just outside New York City are resisting calls to shut that one down. A major accident at Indian Point would endanger millions of people and could become a trillion dollar disaster. Arjun Makhijani from the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research joins us to discuss the developments. Arjun, welcome back to Living on Earth.

MAKHIJANI: Thank you, Steve, I’m glad to be back.

CURWOOD: So, why is PG&E, Pacific Gas & Electric, shutting the Diablo Canyon reactors down by 2025. How safe were they?

Diablo Canyon under construction (Photo: U.S. Department of Energy, public domain)

MAKHIJANI: Well, the Diablo Canyon reactors are in a way fairly typical of other pressurized water reactors with one very big exception, they are on the coast in California in a seismic zone and where new things about the seismology and the activity are still being discovered. There are questions as to whether these reactors could withstand the worst-case earthquake with what is known today. There's a fault much closer to these reactors just offshore than was talked previously for example and renewables and efficiency are cheaper so they are seeing the handwriting on the wall. And I have to congratulate them. I think this is a very, very historic achievement.

CURWOOD: So, this won't be decommissioned as you say in the nuclear business until 2025, so essentially they're rolling the dice that there won't be a major earthquake before then I gather.

MAKHIJANI: Right, it doesn't guarantee safety, and even after the reactor is shut, there are still risks because you have this highly radioactive fuel. It's hot. In 2024 and 2025 the fuel will be moved to a spent fuel pool, a big swimming pool type of structures where it has to be kept cool and if there's a loss of coolant, you could have a catastrophic accident.

CURWOOD: So the shutting down of the Diablo Canyon reactors comes in the wake of other reactors being shut down, nuclear power reactors. I'm thinking of Vermont Yankee. What's going on? What's the trend here?

A view of Indian Point from across the Hudson taken in 2007 (Photo: Daniel Case, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

MAKHIJANI: The trend is these reactors are getting old, and when you get old, you need replacement parts, and so the cost of operating these reactors is going up, and the cost of efficiency is coming down, especially solar energy has dramatically declined in cost. So the competitiveness of existing reactors is declining. In the case of California, there's an additional factor because California has a requirement of 50 percent renewables, mainly solar and wind by 2030. So, as you move to solar and wind, you need flexible resources to complement them, and nuclear power is about the worst there is, and I think PG&E has acknowledged this in their statement.

CURWOOD: So, I gather there is no worry that California is going to be able to replace the power that comes from the Diablo Canyon nuclear complex with renewables.

MAKHIJANI: If you plan to shut down the way the Diablo Canyon shutdown is planned, then you can build up your efficiency, there are explicit targets in the agreement, you can build up the jobs that go with that, you can build up renewables. So, now, what PG&E has done is it has committed to renewables more than is legally required by the state of California, recognizing that if you're getting rid of nuclear, shutting them down, you will need to replace that by zero carbon resources. So planning a shut down I think is the best way forward for really what is a 20th century technology.

CURWOOD: You say the nuclear fleet of power reactors is aging. What's the situation with Indian Point, that complex that is just outside of New York City where there's been a fight, I guess there’s litigation with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission by some NGOs trying to get one of those reactors kept offline?

MAKHIJANI: Well, Indian Point is older than Diablo Canyon. Diablo Canyon is about 30 years into operation. Indian Point's license has already expired. They're allowed to continue to operate by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission because they've applied for a license extension in a timely way, and if they have, that's all that's required. It doesn't say that it's safe, and as you know, Indian Point is only 30 odd miles away from midtown Manhattan. It is the most precariously located reactor from a demographic point of view in case there's an accident. And Indian Point has had plenty of problems. It has had a history of tritium leaks, it has had a history of transformer fires. Certainly for a reactor situated like Indian Point, I think it's pretty egregious that Indian Point has had so many problems and is still operating.

A designer’s mockup of Indian Point done in 1968, prior to the facility’s 1972 opening. (Photo: U.S. Department of Energy, public domain)

CURWOOD: Qualify for me the risks to New York City if something were to truly go wrong at Indian Point.

MAKHIJANI: New York City and the heavily populated areas in the environs - Connecticut, maybe other states, New Jersey, depending on the winds and the type of accident, possibly Pennsylvania, - I think if a severe accident occurred at Indian Point much of that area would become uninhabitable.

CURWOOD: So what are the major safety problems with Indian Point? In your view how risky is that set of reactors?

MAKHIJANI: So the major safety problem that caused Friends of the Earth to file a petition with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission was that there's a certain set of quite sensitive bolts inside the reactor. Now there are hundreds of these bolts in Indian Point 2 there are 800 odd bolts, and in a recent inspection, more than 200 of them were found to be corroded or potentially corroded and two of them were actually missing. So you could have a pretty catastrophic situation that would escalate very rapidly. This is recognized by the NRC as far back as 1998 but they didn't require the reactor operators to do anything. The fact that the NRC has not required routine inspections and the potential damage has built up to 227 bolts, this I think indicates a laxness on the part of NRC that is especially intolerable with respect to a reactor like Indian Point.

CURWOOD: So, what's the future for nuclear energy in the United States and globally?

MAKHIJANI: I think the future for nuclear energy is passed. So we have a certain number of power plants. They will be phased out in one way or another. They're going to become more and more expensive to operate. Renewables and efficiency and now storage are becoming so cheap in combination. So in such a circumstance I think it will go away. The question is how fast, and whether we can do it in an orderly way, and then we come back to Diablo Canyon. I think the Diablo Canyon agreement is very historic because it is showing an orderly way to go from an old centralized inflexible model to a new model, more democratized, renewable, more dispersed and more resilient.

CURWOOD: Arjun Makhijani is President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MAKHIJANI: Thank you so much, Steve. Really good to be back.

Related links:

- Coverage of the Indian Point situation

- LA Times column on the shutdown

- Diablo Canyon website

- Indian Point website

- Indian Point Safe Energy Coalition

- The Institute for Energy and Environmental Research

Beyond the Headlines

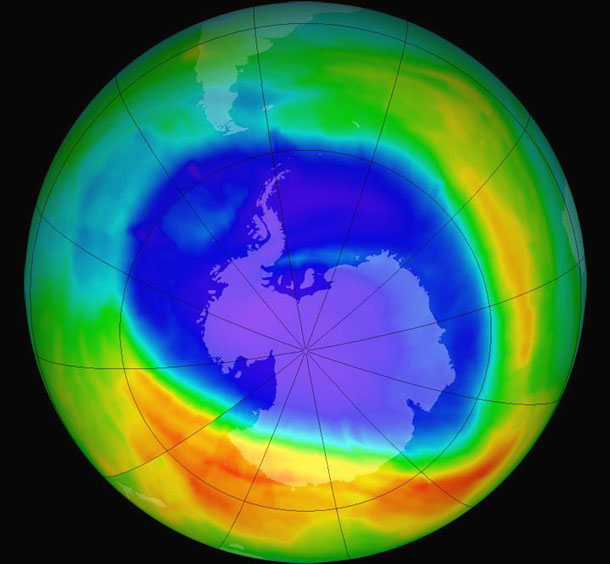

The stratospheric ozone hole shows signs of recovery, according to a recent Journal Science study. (Photo: Stuart Rankin, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Off beyond the headlines now, to catch up with Peter Dykstra. Peter’s with DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and is on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hello, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve, you know, since it’s not always easy to find good news on this beat, let’s bring some major good news front-and-center: In a paper in the Journal Science comes confirmation that the huge ozone hole over the Antarctic has begun to heal itself.

CURWOOD: Scientists have been predicting this would happen, but this is some actual hard evidence?

DYKSTRA: Correct. And research back in the 1980s showed manmade chemicals like chlorofluorocarbons found in refrigeration and spray cans and other things was destroying ozone up in the stratosphere that helped block harmful, ultraviolet radiation from the sun. An ozone “hole” showed up over the South Pole, and a somewhat smaller one in the Arctic, raising concerns that the continued loss of protective ozone would cause skin cancer rates to skyrocket.

CURWOOD: But as I recall, the world’s nations actually got together and they agreed to outlaw the worst ozone destroyers.

DYKSTRA: They did. The Montreal Protocol of 1987 is an environmental treaty that worked, in part because industry got on-board, along with some very unlikely tree-huggers like Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. This new study is confirmation that the ozone holes look like they’re on a path toward extinction.

CURWOOD: And that’s the kind of extinction we can handle, Peter. Many people think we’ll need some equally unlikely tree-huggers to see good news someday on global warming. Hey, what else do you have for us?

DYKSTRA: Well let’s go from the good news to a hotly disputed issue where neither side is happy with the news they’ve gotten. The European Union, long a leader in environmental health issues, turned back calls to block re-approval the herbicide glyphosate – then they also refused industry lobbying to reauthorize glyphosate use for up to fifteen years. And instead the EU set a temporary approval until the end of 2017.

The European Union has temporarily approved the use of the Herbicide Glyphosate until the end of next year. (Photo: Chafer Machinery, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: The World Health Organization has declared glyphosate to be “probably carcinogenic in humans” and there’s also a concern that the chemical can act as an endocrine disruptor.

DYKSTRA: And other studies from the German government and from the EU’s food safety branch have argued in the other direction – that glyphosate is not a likely carcinogen and its health impacts aren’t proven. But that’s where the mess begins.

CURWOOD: Do tell.

DYKSTRA: Environmentalists and many scientists are upset that glyphosate was given even a short reprieve. The chemical industry is frustrated by the uncertainty of not knowing if they’ll be shot down in eighteen months, especially with a proposed merger of two ag. chemical giants, Bayer and Monsanto, being discussed right now. Glyphosate, which is the active ingredient in Monsanto’s herbicide Roundup, is one of the most lucrative chemical products in the world today.

CURWOOD: And the dueling scientific studies are a familiar scenario.

DYKSTRA: They are. And with the dueling scientists come accusations of manipulating that science, with some of the strongest charges being that some EU scientists have financial ties to glyphosate manufacturers. There’s no telling where this one’s going to end, but I’ve got a little possible good news in our history file this week.

CURWOOD: Possible good news is good news enough. Fire away!

DYKSTRA: We’ve had quite a colorful and unfortunate history of killing off trees not with fire nor axes nor chainsaws, but with bugs and disease: Dutch elm trees, butternuts, dogwoods in some areas, and currently insects going after pine trees in the west and ash trees in the east. But 110 years ago this month, the New York Zoological Society published a paper warning against the granddaddy of them all, if in fact a fungus can be a granddaddy. But the chestnut blight nearly wiped out all of the American chestnut trees in the first half of the twentieth century. Chestnut trees used to dominate some American forests. We used them for food, firewood, railroad ties, furniture and we also used them for literature because Thoreau and Longfellow and Robert Frost, among others, all wrote about chestnut trees.

An image catalogued in the Library Of Congress features a forest of blighted American chestnut trees in Page County, Virginia. (Photo: Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: But we almost lost them. So I presume the “possible good news” is the recovery of the American chestnut, huh?

DYKSTRA: Yes. There’s a lot being done, and we may not know the results for nearly a century. But currently, thousands of trees are being bred to resist the chestnut blight, some are cross-bred with stronger Chinese chestnuts and there are two areas where chestnut recovery efforts are intensively focused: National Forests, that’s not much of a surprise – but also reclaimed coal mining land throughout the Appalachians. It’ll be a long time before we know if those majestic spreading chestnut trees will make a grand comeback in forests and maybe even in literature.

CURWOOD: To give renewed shade to the village smithy, huh?

DYKSTRA: Right.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News – that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks, Peter, we’ll talk again soon.

DYKSTRA: Thank you Steve, we’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Read the paper: “Emergence of healing in the Antarctic ozone layer”

- The EU’s Temporary Glyphosate Extension

- About the American Chestnut

- Chestnut Blight

- 1907 Annual Report of the New York Zoological Study

- LOE’s recent story on glyphosate

[MUSIC: Project Trio, Hungarian Dance No.5, Instrumental, Johannes Brahms, Harmonyville Records]

CURWOOD: Just ahead...some of the joys of eating what you grow. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Eddie Pennington, “Walking the Strings,” Eddie Pennington Walks the Strings, Merle Travis, Smithsonian Folkways]

Squash Bee: The Pollinator That Follows Farmers

Peponapis pruinosa bees gather pollen from a squash flower (Photo: USDA Agricultural Research Service, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, and I’m Steve Curwood. The US Fish and Wildlife service has announced it will issue an endangerment ruling on North American Monarch butterflies within the next three years. The iconic butterfly is just one of many pollinators in trouble, thanks to human activities; the honeybee is another. But science has also found a pollinator that follows human activity. The squash bee moved beyond its native range in the Americas as people spread the cultivation of indigenous squashes. Margarita Lopez-Uribe studies evolutionary biology at North Carolina State University and co-authored the paper laying out this connection. She joins us from her lab. Margarita, welcome to Living on Earth.

Zucchini and many other squashes are pollinated by squash bees (Photo: Sea Coast Local, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

LOPEZ-URIBE: Hi. Thank you.

CURWOOD: What are we really talking about when we say the squash bee? How different are these bees from the familiar honeybee?

LOPEZ-URIBE: Well, they are very different. There are about 20,000 species of bees in the world and the honeybee is only one of them. So when you're talking about the squash bees, actually there are about 20 species that specialize in squash pollination, and the one that I focus on is only one of those 20, and it's called Peponapis pruinosa.

CURWOOD: And what does it look like?

LOPEZ-URIBE: The bee is about the size of a honeybee, but it looks a little bit different to someone that has a trained eye. And one of the big differences morphologically is that the honeybee collects the pollen in a structure in the hind legs. It's called a cubicula It's basically a basket. So the honeybees visit the flowers they collect the pollen, they put a little bit of nectar in the pollen and then they make these wet balls of pollen that they store in those baskets in the hind legs. The squash bee does not have that basket. It has an incredibly long and very conspicuous hairs in the hind legs, and so the pollen gets actually stuck in those hairs, and one of the features of the squash pollen is it has very large grains of pollen, so it easily gets attached to those hairs in the hind legs.

Squash bees are solitary and make their nests beneath squash plants (Photo: Silar, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: Now, tell me the crops that they pollinate for humans. When you say squash, what are we talking about here?

LOPEZ-URIBE: Well, they specialize in pollenization of one plant genus, the genus Cucurbita and that plant genus happens to actually be the genus of a lot of different crops. So we are talking about squash, pumpkin and zucchini. All of those crops are actually part of the genus, the plant genus Cucurbita and they're all pollinated by these squash bees.

CURWOOD: What's neat about your paper is that you figured out the bees spread their range thanks to the cultivation of squash. What prompted you to look at this?

LOPEZ-URIBE: Well, so if you look at the distribution of the bee today, for a big chunk of their distribution they are only co-distributed with plants that are domesticated by humans, and so we already predicted that the bee had expanded its range outside of the ancestral range of the plants that were not domesticated by humans. What I did was I look for genetic markers to actually see if there were signatures of the genetic level that could corroborate this hypothesis that we had, and that's what we found, that indeed this bee expanded dramatically thanks to the cultivation of these crops outside of the native range of the plants that are not domesticated.

CURWOOD: What surprised you most about your findings?

Squash bees’ long hairs allow the pollen of plants in the Cucurbita genus to stick to their legs. (Photo: The Packer Lab, Creative Commons)

LOPEZ-URIBE: Well, there were a couple of things that were very interesting. One thing was the route of the movements of the bees. So, these bees are very very abundant in northeastern North America. One possible way they got there was actually kind of you know like along the east coast of North America, but actually what I found is that the bees moved through the midwest and then colonized the northeast of North America. So they kind of like took the longer route to get there. The other interesting finding was even though this was a rapid expansion, we did find some signatures of severe bottlenecks. What happens is that even though these bees have been in eastern North America for quite a while – we’re talking about thousands of generations - they still show very low genetic variability. This is interesting and it's something that I'm really curious to keep investigating because what I hypothesize is that the fact that these bees are so tightly associated with crop management and agricultural systems that means it probably there is something that we're doing with the crops of these bees are relying on that is keeping the genetic variability of these populations extremely extremely low. And that would make them really vulnerable to changes in the environment.

CURWOOD: You term these bees as being solitary, but, of course, how do they reproduce then?

Instead of long hairs, honeybees use ‘baskets’ on their legs to carry bundles of pollen in. (Photo: Aphaia, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

LOPEZ-URIBE: Well, the lifecycle is very different. So what happens is that I told you these bees nest underground and they have a yearly lifecycle. Usually by midsummer, the females and males emerge from the ground, they mate, all females are fertile, and then the females who have mated, they start looking for areas where they can make their own nest. Once they find a good spot, they make the nest, they start collecting pollen and nectar, they lay eggs, they close those nests and they never see the babies. They die that summer, and then the next year those eggs of course go through the whole development and adults emerge and the cycle starts again.

CURWOOD: I imagine that if they build their nests in the ground, it's close to the plants. What happens when the plows come through?

Common agricultural practices like tilling can harm the squash bee by destroying their ground nests (Photo: CC BY-SA 2.0)

LOPEZ-URIBE: Yeah, so that's one of the things that I'm worried about, and that I think it's probably driving some of these low genetic diversity populations is the fact that agricultural systems of squashes and pumpkins actually include what we call crop rotation and soil tillage, and so I think a large number of these individuals just dies every year as a result of these agricultural practices.

CURWOOD: So, if I understand this, honeybees can also pollinate squash, so what's the difference here?

Margarita López-Uribe with a honey comb. Social honey bees store food, but the solitary squash bee does not. (Photo: courtesy of Margarita López-Uribe)

LOPEZ-URIBE: Well, there are major differences. One of them is the time of the day that these bees forage. So Peponapis pruinosa is a very early morning bee. When I was doing fieldwork for the study, I would have to get up really really early because most of the foraging happens the first one or two hours of the day. Honeybees and other pollinators of these crops like bumblebees, they usually pollinate later in the day and for much longer. The other difference, and this is something we don't really know much about, is it seems to be the pollen of these crops has some chemical properties that make the pollen highly unattractive to most bees. Peponapis pruinosa pollinates squashes and pumpkins because the female bees are collecting the pollen. So in the movement between the flowers they are transferring pollen grains between flowers. The honeybee goes to the flowers only for nectar, and so it's a much less specialized behavior in terms of the foraging. We know a lot about the honeybee but very little to almost nothing about the other thousands of the species of bees in this planet.

CURWOOD: Margarita Lopez-Uribe is a postdoc researcher at North Carolina State University. Thanks for taking the time today.

LOPEZ-URIBE: Thank you so much. It was a pleasure.

Related links:

- About the paper, “Crop domestication facilitated rapid geographical expansion of a specialist pollinator, the squash bee Peponapis pruinosa”

- More about squash bees

- About Margarita López-Uribe

- Watch “Journey of the Squash Bees”, a short video featuring Dr. López-Uribe

Gardeners Create a Bountiful Backyard and Find Love

Asian pears growing in Holyoke, MA (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

CURWOOD: For many gardeners in the northeast US, the squashes are starting to flower and set fruit, kicking off the anxious watch for the squash vine borers. Of course, some gardeners are more expert than others – and in spring a while back, Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb went to visit a pair with some honed skills. They’re permaculture gardeners Eric Toensmeier and Jonathan Bates, whose book "Paradise Lot" chronicled how they created a perennial food forest in a degraded backyard in Holyoke, Massachusetts. Here’s her account of nibbling her way through their garden.

BASCOMB: From the street, this gray duplex doesn’t look like much. But around the back is an urban oasis. The yard is just 1/10th of an acre but produces almost all of the fruits, vegetables, and eggs two families need. Eric Toesnmeir took me on a tour of his garden.

The view from above the gardens. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

TOENSMEIER: This is the season of perennial vegetables, vegetables that come back every year and make food. So, down here is Turkish rocket, which looks a bit like a dandelion this time of year but soon it will make these wonderful broccoli rabes, like an 8 or 10 inch mustardy tasting broccoli that are absolutely delicious.

BASCOMB: Eric says, what he and his gardening partner Jonathan Bates have created is a permaculture food forest.

TOENSMEIER: So, we’re trying to in this area imitate the structure of a forest with trees and shrubs and herbaceous species and vines and fungi but have them be both edible for us and working together as an ecosystem.

BASCOMB: At the lowest level there’s the broccoli- and ramps, ginger and violets. Above them grows a gumi bush, one of their many Asian species. It fixes nitrogen and produces berries that taste a bit like rhubarb. Shading over them all is an American persimmon tree.

A goumi bush fixes nitrogen and provides small red fruits. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

TOENSMEIER: Permaculture is meeting human needs while improving ecosystem health.

BASCOMB: Eric says when they bought the house, the yard needed help. All it would grow was crab grass.

TOENSMEIER: We had 3 different kinds of terrible soil. There was sand and gravel fill and there was a compacted clay with chunks of concrete and rebar in it. And the last piece where we are now was a sandy acid soil with low levels of lead.

BASCOMB: Eric and Jonathan took one look at this barren plot of bad soil and felt inspired.

TOENSMEIER: We actually thought it was perfect. We wanted to be somewhere where the scale at which we were operating was really relevant to lots of people. So, we were looking to be in the city. We wanted to find some sweet hearts and we felt like we’d have better luck in the city than in the country where we were more likely to run into a bear than a woman. And we wanted a place that was as beat up as you can imagine because we wanted to set the bar high and say, “If we can do it you can totally do it.“

BASCOMB: So what should we look at next?

TOENSMEIER: Oh, let’s visit at the chickens.

Chickens are an integral component to the health of Paradise Lot. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

BASCOMB: Yeah!

[SFX WALKING SOUNDS CROSS FADE TO CHICKEN SOUNDS] 2:21

TOENSMEIER: So, these are our girls. We have three chickens and they’re a really important part of our backyard ecosystem. We feed them lots and lots of leaves from the garden. Excess vegetation both from our own crops and weeds and they just love it.

BASCOMB: Eric picks a handful of weeds and feeds them to the chickens through the fence.

[SFX SOUND OF CHICKENS EATING UNDER PREVIOUS GRAPH AND NEXT IN THE CLEAR BETWEEN]

BASCOMB: And he says the bulk of the chickens’ food comes from garden weeds and bugs.

TOENSMEIER: I feel like we wouldn’t really be able to do our garden well without them. It’s so important for them to take the excess biomass that’s produced in the garden and convert it into stuff we can eat directly like eggs and eventually meat and all this fantastic material that we are standing in right now. The bedding plus manure plus weeds accumulates into a great big deep layer by the end of the year and that is beautiful compost material and they’ve sped up our fertility cycling very dramatically.

BASCOMB: Do you name your chickens?

TOENSMEIER: We don’t.

BASCOMB: Probably a good practice.

TOENSMEIER: Any animal you are going to eat, you don’t want to name. Unless you name it Christmas or Thanksgiving for the meal at which you are going to eat it.

BASCOMB: How many eggs do you get a day?

TOENSMEIER: In the summer each one lays one egg. In the winter none of them do. In the spring and fall somewhere in between. They average 220 eggs a piece per year. So, that’s quite a lot. It makes a big difference in our diet.

BASCOMB: Though the chickens are vital there is a problem.

TOENSMEIER: It’s completely illegal to have chickens in Holyoke. We didn’t have any trouble with them initially and then at one point our previous next door neighbors over here were raided for selling drugs. While the police were here for that they called in our chickens, which is about an equivalent crime of course…. 3 chickens and selling cocaine. So, we took them away to the country for a couple weeks until the heat cooled down. And then we brought them back. What we were told if there’s another complaint we would get a $25 fine and we thought we could live with that alright.

BASCOMB: I would think too you could probably buy off the neighbors with a couple of eggs.

TOENSMEIER: And strawberries. Strawberries are the best bribe we have.

Eric says fresh, organic strawberries are the best bribe they have for neighbors. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

BASCOMB: What else should we see now?

TOENSMEIER: Let’s go visit the bamboo grove and the best fruit production area we have in the back corner.

BASCOMB: Sounds good.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: We walk down the wood mulch path to a corner where tall thin bamboo reeds rustle in the wind. It’s a dense grove that creates a private space in the garden. Next to is the fruit orchard.

The yard was a blank slate when they bought the house. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

TOENSMEIER: This is our Asian pear, it’s just flowering fully for the first time today. We don’t have a lot of room so it’s on a dwarfing root stock that keeps it really small. And it has 3 different varieties grafted on to it. An early season fruit, a mid season fruit and a late season fruit all on the same tree.

BASCOMB: They get about 150 pears a year, not too shabby for a tree just 12 feet high.

TOENSMEIER: In the same area we have blueberries and service berries, and raspberries, and hazelnuts, and grapes, and rhubarb, and perennial leaks, and elephant garlic, and strawberries so in just this tiny corner which is about 20 by 25 we have all those different plants fruiting and producing excellent food for us.

BASCOMB: Such diversity is impressive and I can’t help but compare it to my backyard garden. The only things I have growing are some pea plants and weeds. But Eric says anyone can create this kind of garden. Just start with something simple.

TOENSMEIER: I think if people are going to start with one thing it would be berries. They don’t take up a lot of space. A lot of them can handle some shade. They’re beautiful, they taste good and they’re mostly very easy to take care of. And every year you can add another bed. We didn’t do all this in one year either.

Old logs do double duty as mushroom habitat and borders for garden beds. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

BASCOMB: The garden beds are bordered with old logs. They inoculated the logs with spores to grow edible mushrooms but Eric says they also form a critical habitat.

TOENSMEIER: When you roll one over all kinds of creepy crawly things come out which are part of our decomposer ecosystem and they’re part of our pest control system as well. A lot of predacious ground beetles for example live under the logs and then go out and eat pests and even eat weed seeds.

BASCOMB: And the system works. In 7 years they’ve never had to use pesticides of any kind in the garden. Instead they provide habitat for garden helpers like ladybugs and praying mantises. But, Eric says, it’s wasn’t just beneficial insects that he and Jonathan hoped their garden would attract.

TOENSMEIER: One of our goals for the garden was to attract mates. We felt like the birds that put shiny things in their nest to attract a mate. We planted fruit trees. It’s not like we literally thought that would be all someone was attracted to obviously but it doesn’t hurt to distinguish you in the market place of other potential mates if there’s something unique and interesting and delicious about you and your backyard.

Eric and Marikler were married in the bamboo grove of Paradise Lot. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

BASCOMB: And that worked too. Next to the bamboo grove beneath a flowering mimosa tree Eric married Monteclair and Jonathan married Meg .

[SOUND OF WIND IN THE BAMBOO]

BASCOMB: As if on cue, Jonathan joins us between the bamboo and the greenhouse.

BATES: My name is Jonathan Bates and I’m a co-gardener here with Eric and landscape. He’s been a mentor for over 10 years now.

Jonathan and Meg tied the knot at Paradise Lot. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

BASCOMB: And they’re constantly experimenting. Jonathan designed and built the greenhouse where they grow some annual vegetables and tropical plants.

BATES: We were able to overwinter a hardy avocado and it’s already grown 6 inches since Spring started in there.

BASCOMB: You’re growing avocado in Massachusetts?

BATES: Yeah.

BASCOMB: I’ve got to see that.

BATES: We can go check it out.

BASCOMB: Great.

[SFX WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Inside the greenhouse it’s humid and much warmer. Jonathan says walking in here is like going on vacation.

BATES: Instead of spending a couple thousand dollars going to Florida with a family for a week we invested that money in building this greenhouse and now we’re living in northern Florida. So we have things like citrus, Chilean guava, fig, hardy avocado, these are called tree collards. They get to be 11 feet tall and they are perennial they grow them all year round.

BASCOMB: Recycled granite curbstones define a raised bed inside the greenhouse. There’s also three large tanks containing an aquaponics system with catfish and 800 gallons of water. Jonathan says the granite and the water collect heat during the day and radiate it back at night to make the greenhouse up to 10 degrees warmer.

[SFX SOUND OF RUNNING WATER, PUMPS] 8:31

BASCOMB: They plan to expand the system and grow more fish for food in the future. But right now there are plenty of things ready to eat and they’re eager for me to try them. Jonathan tears out a handful of watercress.

[SFX TEARING PLANTS]

BATES: It’s a little spicier now because it’s about to go to go to flower but we had a good three month run for the watercress.

BASCOMB: Mmm… it’s pretty bitter.

TOENSMEIER: There’s tree collards in here to eat right now but if we come outside we have garlic chives.

BATES: We can get some violet flowers for you.

[SFX… SOUND OF PICKING FLOWER, FAINT CHEWING SOUND]

BASCOMB: Mmm… they’re sweet.

BATES: Here’s some miner’s lettuce. We don’t have a lot of it but they’re good to eat.

BASCOMB: Oh my gosh, a carrot!

TOENSMEIER: These are real nice. These are last year’s carrots. This is Nantes, which is like a sweet dessert carrot.

(Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

BASCOMB: A dessert carrot. You talk about it like it’s wine.

TOENSMEIER: We’ve sort of started to become connoisseur of different vegetables here, which is really fun.

BATES: Do you like sorrel?

BASCOMB: I don’t know.

BATES: Let’s try it.

[CHEWING SOUND]

BATES: So, it’s lemony tart.

BASCOMB: Mmm! It’s tart! [laughing]

BATES: You can tell that we don’t eat a lot of it.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I can see why. (laughing)

BATES: Do you like black licorice?

BASCOMB: Sure.

BATES: This is sweet Cicily.

BASCOMB: Thank you.

BATES: Mostly we grow it for the flowers that bring beneficial insects but this is a traditional sugar substitute in Europe. And then one last thing I can show you is the water celery. It has kind of a parsley celery flavor.

BASCOMB: Thank you

[CHEWING SOUND]

BATES: This is a very popular tropical herb in Asia, Southeast Asia. Grown in the water. Here it can grow terrestrially in partial shade.

Sea kale is a perrenial plant that tastes like brocoli but more tender. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

BASCOMB: That’s a pretty impressive plant.

BATES: Yeah. Did Eric show you the sea kale over here?

[SFX WALKING SOUNDS]

BATES: So, you gotta try a floret.

[SFX FLORET CRACKING]

BATES: So, it’s a perennial kale that I think is as good as broccoli, annual broccoli.

[CHEWING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Where do you guys get these? I’ve never seen sea kale in my local nursery.

BATES: Originally sea kale was a seed we bought from a seed company way back 10 years ago. So some of these plants are 10 years old. But now if you want to get a sea kale plant you can get them from foodforestfar.com.

BASCOMB: Is that your company?

(Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

BATES: That’s my nursery, yeah. [LAUGHS]

BASCOMB: So, the garden has turned into a business for Jonathan. When they started this project they had simple goals… to walk out in the yard and get a handful of fruit each day of the summer, greens every day of the year, and find the loves of their lives. Mission accomplished on all accounts. Jonathan says he knew the garden was a success after 5 or 6 years when the plants really took root and started to produce in abundance.

BATES: There’s an explosion of life really and at that point this idea of mimicking a forest ecosystem really hit home. It’s like, we really did it.

BASCOMB: For Eric, success was being able to share the fruits of his labor and inspire others.

TOENSMEIER: Over a thousand people have come and visited the garden and a lot of them have gone home and done this. They buy plants from Jonathan or we send them home with seeds. Being in the city has been really good for building a movement.

BASCOMB: Eric and Jonathan say they might one day move out of their paradise lot to larger piece of land in the country but for now they are happy to be here, building a grass roots movement growing anything but grass.

For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in Holyoke, Massachusetts.

Related links:

- Eric’s Blog

- Food Forest Farm

- Paradise Lot Website

[MUSIC: Taj Mahal and Toumani Diabate, “Queen Bee,” Kulanjan, published by Prankee Music/One Foot Music (ASCAP)/Rykomusic, Inc.(ASCAP), Hannibal]

CURWOOD: Coming up...talking tyrannosaurs. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward.

This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: New Black Eagle Jazz Band, “Sweet Fields,” Higher Ground, traditional blues, Black Eagle]

Finding New Tyrannosaurs

David Hone excavates a tyrannosaur fossil in Xinjiang, China. Opaque as they may seem, bones provide an incredible amount of information for those who know how to decipher them. (Photo: courtesy of David Hone)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. The name means Tyrant Lizard King and in 1905, the New York Times called Tyrannosaurus Rex the absolute warlord of the earth. T Rex fossils were first discovered in 1874, and now the group includes some 29 different species, with a new one identified just about every year. Tyrannosaurs were extremely successful during their 100 million years on Earth. They were active on four of the present continents, and have been found in Britain, where David Hone now studies them at Queen Mary University of London. His new book, The Tyrannosaur Chronicles, details the anatomy, evolution, and ecology of these fearsome carnivores. We called him up, but before we talked Tyrannosaurs we challenged David Hone to name as many of the family as he could in 15 seconds...go!

HONE: Oh boy. Guanlong, Dilong, Yutyrannus, Lythronax, Alioramus, Tyrannosaurus, Tarbosaurus, Daspletosaurus, Albertosaurus, Gorgosaurus, Bistahieversor, Qianzhousaurus. [BELL RINGS] Damn it. I know there‚ a couple more and I’m struggling now.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] So, David, this was a widespread family with lots of variety?

HONE: They were really quite diverse. So the first few species that we have around 165 million years ago where about the size of something like a Labrador and actually some of the early species of Tyrannosaur also had these big elaborate bony crests on their heads so actually had a fairly different profile, and they didn't have the giant heads and they didn't have the little arms or things like Tyrannosaurus and the very last of the Tyrannosaurs.

CURWOOD: In your book, you say, "As I'm writing this, there are likely to be more species identified and my book will be out of date even before it hits the bookstore."

HONE: That's already happened. So, in February – so the book was already at the publishers, a new Tyrannosaur was named from Asia. And actually as I was writing the book, three new species were added. I wrote that line of "this book is going to be out of date by the time this book is published" and then I kept having to edit that line because it was already getting outdated faster than I could update the book. [LAUGHS]

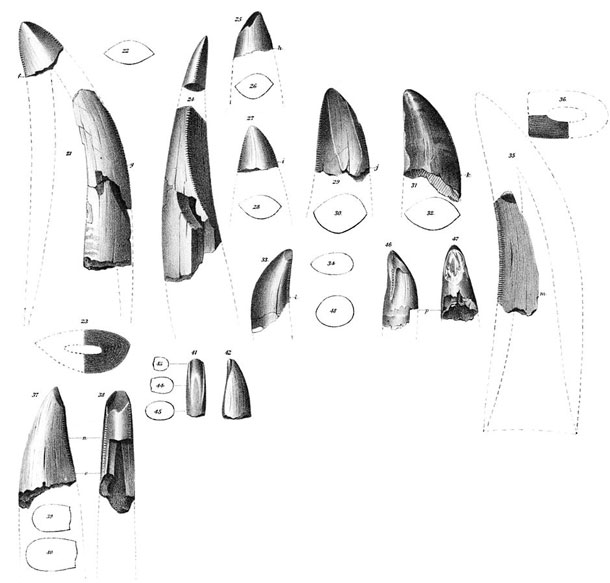

CURWOOD: Now, you're a scientist so this is a totally unfair question, but what's the simple explanation of what makes a Tyrannosaur a Tyrannosaur?

David Hone’s new book, The Tyrannosaur Chronicles, details the anatomy, evolution, and ecology of the world’s most iconic dinosaurs. (Photo: courtesy of David Hone)

HONE: Happily, these one of the rare groups where there’s a fairly simple explanation for this. The very front teeth in the jaw have this very odd profile they have a flat back pointed into the mouth and a very round front pushing out of the front, and this is actually a feeding adaptation. And the other thing they have are the bones called the nasals. There's two bones you have one on the left and one on the right. Basically all animals have this. But in the Tyrannosaurs they're fused together into one big block.

CURWOOD: Ah, the teeth are the better to eat you with, I gather huh?

HONE: Well, specifically for feeding they have these giant kind of robust bone-crunching, killing teeth down the sides of the jaw, but at the front they have yeah these kind of flat, blunt little basically scraping teeth. The best analogy I can give is take a cookie like an Oreo, peel off one biscuit and how do you get the cream off. Everyone puts it in their mouth and pulls it forward and scrapes the cream off on their teeth. And this is how the Tyrannosaurs were feeding, and we know this actually because we have the bones that they were feeding on and they leave exactly these marks. We see a whole bunch of very blunt, but deep grooves in the bone pulled a straight line together. They’re basically scraping the muscle off the bone with these odd little teeth.

CURWOOD: So what did these animals look like and how do we know this?

HONE: Well, the big ones were big. They walked on their back legs. I mean the fact they've got tiny arms is a pretty big giveaway but we've also got footprints for these animals. We conceded that definitely walking around on their back legs. We also don't see any tail traces – so we know the tail is up off the ground, and Tyrannosaurs probably had feathers. There's an early thing from China called Dilong which has some patches of feathers preserved alongside it, and then there is a much larger Tyrannosaur – seven or eight meters long from China – called Yutyrannus, and Yutyrannus basically is preserved with feathers from the tip of its nose to the tip of its tail. This thing was covered, and therefore the obvious inference is that the other Tyrannosaurs were too, we just simply haven't found the feathers yet. And that's not a big surprise, feathers do not preserve very often.

CURWOOD: So in your book you discuss trying to figure out the color of these things. How would you do that?

The slow process of unearthing a tyrannosaur skull, shown clockwise from top left. This one belongs to a Gorgosaurus, a genus that lived in western North America between 76.6 and 75.1 million years ago. (Photo: courtesy of David Hone)

HONE: The short version is, at least part of what makes up the color in feathers - and indeed it does actually in hair and some other things as well – are these tiny little packages called melanosomes and they basically contain these color pigments. Imagine if you went to a DIY store or something like a hardware store and all the paint was sold in different shaped tins and the tins actually correspond to the colors that are in them. So black always comes in a long, thin tin, blue always comes in square tin and yellow ones comes in a triangular tin or something like that. As it happens, the way the melanosomes are laid down, different pigments correspond to different shapes of package. So actually you don't need to see the actual color to know what color was in there as long as you've got the shape. There are some huge limitations to this. So, for example, we can only do general shades. So, red basically means anything from kind of, bright orange all the way down to dark brown. Then, there are some complications because you can actually then change the colors often quite dramatically by how you orientate the tins relative to each other and that actually information is probably lost during the decay. So we never see blue, for example, because blue is a color which is basically built on structure and not on melanosomes.

CURWOOD: So with all these feathers, I'm wondering – what does science have in the way of DNA from Tyrannosaurus?

HONE: Nothing at the moment unfortunately. Maybe maybe maybe one day we'll find something like that but even if we do you'd be talking about tiny fragments of bits. You know you'd be lucky to go, yes this is probably a reptile, let alone this has something unique about it which is Tyrannosaurus. So don't get your hopes up for Jurassic Park sequel any time soon.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about the life of the Tyrannosaurus. How close were they to the top of the food chain?

HONE: The basic life of them as indeed for most animals was short because as with animals in the modern world most things don't survive past their first year. In terms of what they're doing ecologically, of course, it varies enormously. The first few Tyrannosaurus were two to three meters long, forty, fifty kilos, these were pretty small carnivores in their ecosystem – the equivalent of something like a fox or jackal or badger now. So they were making their way in the world as it were, but there's lots of big threats out there to them. When you get through to the later giants, things like Tyrannosaurus and in Asia things like Tarbosaurus, they are the biggest carnivores out there, in fact, they are the biggest carnivores on Earth at this point, somewhere in the range of five to seven metric tons. These are seriously big animals and the next biggest carnivore is like twenty kilos compared to a five, seven-ton monster. This is an enormously big gap in size. You would expect to have anything from about three to six or even seven big carnivores and frankly I have no idea why ... I have yet to come across anyone who has any idea why. The obvious conclusion is that it's the younger animals that are kind of filling in those ecological niches. A half-grown Tyrannosaurus is seven, eight meters long and weighs a couple tons. Okay, that's filled that midsize carnivore niche. That's an explanation, but it doesn't explain why we don't see that for some of the earlier ecosystems, so it's very very odd.

CURWOOD: Well, and science has to have more mysteries to solve doesn't it, huh? So how fearsome were they, really? I mean, what did they have in the way of cute and cuddly ones as well?

Relative to its head, this T. rex’s eye sockets may seem small. In fact, they are the largest of any known terrestrial animal of all time. That means that T. rex, like its tyrannosaur relatives, had excellent eyesight – possibly better than any other land animal ever. (Photo: Scott Robert Anselmo, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 3.0)

HONE: Well, the small ones would've been fairly cute and cuddly though they probably would have taken your arm off if you were standing in front of them. And of course the juveniles, a hatchling was actually was really pretty small. I mean a hatchling Tyrannosaurus might be less than a meter long. So this is an animal that has to get from under a meter to over twelve meters to become up a full-sized adult. So, that's a colossal amount of growth, and so actually, yeah, for a normal population there would have been lots of baby and young Tyrannosaurs knocking around. And bare in mind, a young Tyrannosaurus can be an animal seven meters long and weighs a ton, but it's still barely an adolescent by human standards.

CURWOOD: How do they find their food? The big ones, I mean, obviously everybody knows they're coming.

HONE: They may not need to worry about whether things can see them coming because what the big Tyrannosaurs were built for was actually long-distance running. They were pretty quick. They couldn't run in one sense – you know the actual biomechanical definition of running, they were probably not getting both legs off the ground at once. What they had was actually – what’s effectively a very quick walk, but when you're that big with legs that long you still cover a lot of ground very quickly, so actually they may well be doing is effectively coming over the horizon approach, right? You don't care if the prey see you coming, you just run at the herd or the group or the individual that you selected and try and close the gap faster than they can outpace you. They might be faster in the short time but as long as you can keep them in view you will go for longer. The second solution which I actually posit in the book and don't think has been suggested before – this is one of the really great things about writing a popular science book rather than a piece of science literature – you can speculate a bit more freely. There is an obvious solution to this, which is be nocturnal. These animals four, five meters high to the top of the head. There probably is no cover they can hide in, but these are animals that we know that had exceptional eyesight. And one of the big correlates of being nocturnal is having exceptional eyesight. This would actually probably offset part of the problem of not being able to hide when you're that big. I freely admit this is complete speculation, but I think it fits if you have the limited things that we know about.

CURWOOD: So how do you know that they had such great eyesight?

HONE: Actually the very short version is that they have enormous eye-sockets. One thing we do know from very careful studies of mammals and birds in particular, owls actually serves directly relevant. Basically the bigger the eyeball you can physically fit in the skull, the better it is at taking in light and details. And people have said the Tyrannosauruses have got little eyes, and compared to the size of its skull, it does. They look small but it's not relative size that's important, it's absolute size, and they are absolutely enormous. In fact, the eyes of Tyrannosaurus when measured, or at least the eye-socket are the largest of any terrestrial animals of all time. So, in fact, this animal in some way, shape or form the best eyesight of any animal on land that we know of all time.

Tyrannosaurs’ unique scraping teeth – round at the front and flat at the back – are one characteristic that tells paleontologists they’ve dug up a tyrannosaur. (Photo: Joseph Leidy, Wikimedia Commons CC)

CURWOOD: David, I have to ask you this. On the big Tyrannosaurus, T-Rex, how do they reproduce? I mean you’d think sex would be kind of risky with all those teeth?

HONE: [LAUGHS] Carefully is the obvious answer. In terms of actual physical congress, let's say, actually is quite awkward because they are these big bipeds, they are big heavy animals falling over is actually quite big deal for them and yet you need to get relevant parts together, and that's quite difficult since it under the base of this big and actually very muscular tail. The obvious conclusion is that the male had something – and I'm not being purant in this term – an intermittent organ in other words something that poked out or could be poked out. This is not unique to mammals, actually lots of birds, in particular ducks. You may not want to Google this from your office but I can highly recommend looking up some of the biology of duck reproduction and that's actually probably the best way that you could get a male and female, seven ton carnivores with little arms that might fall over, together, but I have to add to that because we don't actually know for sure.

CURWOOD: There's a fascinating part of your book where you talk about Tyrannosauruses functioning as part of a larger ecosystem. Describe for me what these ancient ecosystems might have looked like, and the role that the Tyrannosaurus played.

HONE: A Tyrannosaurus would actually have lived in an environment, which would look a lot alike it did today. We had grasses by this time, we had big conifer forests, we had big open plains. So actually some of the big forests in North America, you know, it would recognize a lot of those plants. More interesting one is Tarbosaurus – so this is kind of the Asian equivalent if you'd like which lived in Mongolia in Northern China. And at that time, actually much of the Gobi Desert is a desert now. That's what the environment looked like sixty-five, seventy million years ago. So this is a very, very different environment for a very similar animal.

CURWOOD: So what do you wish people knew about dinosaurs and is their dinosaur myth you can bust for us?

David Hone, Lecturer in Zoology at Queen Mary University of London, regularly blogs about dinosaurs in addition to his own research. (Photo: courtesy of David Hone)

HONE: One thing that comes back again and again is you can't know that, you clearly made that up. I've done stuff online and written articles and I do Q&As on websites and stuff. And what they see is I go actually we do know what color they were, sort of, and we know that they can run at the speed, and we know that they were bad at turning or we know they fed with their front teeth. How can you possibly know that? Well, they have this unique tooth shape that suggests that they are doing something with it. We have bite marks on bones that match tooth shape. And then they go, oh! And it's like, right.

Dig into it. See what it is that we know and how that we know this because research is doing some phenomenally clever and impressive stuff, and there are some incredible specimens which give us these details. In terms of busting a dinosaur myth, it's the one which is almost at a tipping point because I increasingly come across people who go, ‘I knew that,’ and they're not that impressed, but remember that the dinosaurs aren't extinct. Birds are dinosaurs. Birds are the direct descendants of dinosaurs. Evolutionarily and taxonomically, they are dinosaurs.

CURWOOD: What's left in terms of the Tyrannosaurus? Are they all extinct?

HONE: Yes, so Tyrannosaurus did go extinct in the great extinction 65 million years ago. Tyrannosaurus is actually one of the last non-avian dinosaurs that we know of. You know, that's the guy who would stand on a hilltop and seen the meteor coming. So the birds branched off from a group of dinosaurs actually very close to the Velociraptus. There was a little type of branching event and one group went on to produce stuff like Velociraptor and another group went on to produce the birds. So birds go back to about 150 million years ago.

CURWOOD: David Hone is a lecturer in zoology at Queen Mary University of London. His new book is called "The Tyrannosaur Chronicles.” Thanks so much for taking time with us today, David.

HONE: Thank you for having me on.

Related links:

- David Hone’s website

- “Lost Worlds,” David’s dinosaur blog hosted by the Guardian

- David’s personal dinosaur blog, “Archosaur Musings”

- A new tyrannosaur species, discovered as the Tyrannosaur Chronicles went to print

- The Tyrannosaur Chronicles

[MUSIC: Mark Isham, “Mr. Moto’s Penguin (Who’d Be an Eskimo’s Wife?),” Vapor Drawings,

Windham Hill]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Anica Green, Jay Feinstein, Emmett Fitzgerald, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Charlotte Rutty, Adelaide Chen, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page – it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world‚ most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth