July 22, 2016

Air Date: July 22, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

America’s Deadly Power Plants

View the page for this story

Pollution from power plants in Ohio and Pennsylvania in 2015 caused up to 4,400 premature deaths across the country, according to a new study. And the health damages of these 77 plants cost an estimated 38 billion dollars, mostly in already disadvantaged communities. Elena Krieger of PSE Healthy Energy and host Steve Curwood discuss the disturbing death toll of fossil fuel power plants. (07:05)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

The Republican National Convention mostly ignored global warming and the environment. Meanwhile the GOP platform proposes dismantling the EPA, and calls coal an “abundant, clean, affordable reliable” energy source. Peter Dykstra of EHN.org and host Steve Curwood reflect on the convention and the Republican priorities the platform lays out. (05:25)

High Tech Hunt for Methane Leaks

/ Reid FrazierView the page for this story

As federal and state governments attempt to reduce methane leaks from oil and gas operations, scientists are still trying to figure out just how much of it does escape from pipes, valves, tanks, and gas wells. The Allegheny Front’s Reid Frazier takes a road trip with researchers trying to pin down leaks in one of Pennsylvania's biggest drilling areas, and reports on the high tech detection methods scientists and companies are employing. (07:00)

Emerging Science Note: Walking Fish

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

You might imagine that amphibious fish, like mudskippers, which spend time in water and on land, would be a rare phenomenon. But Australian researchers now say that the evolution of amphibious fish is more common than we thought. In fact 130 species of fish from 33 families have evolved amphibious behavior, as Living on Earth’s Don Lyman reports. (01:45)

The Value of National Parks

View the page for this story

Research from Harvard and Colorado State finds that Americans value maintaining the National Parks system through their taxes at over 30 times its annual appropriations. Host Steve Curwood sat down with Harvard professor Linda Bilmes to discuss why Americans care so deeply for these iconic places and how to put their future and protection on a sustainable financial footing. (08:15)

The Hour of Land

View the page for this story

Author Terry Tempest Williams calls the US national parks “breathing spaces” for the American public. Her new book The Hour of Land creates a series of lyrical portraits of national parks that hold personal significance. Host Steve Curwood and Terry Tempest Williams discuss the national parks as places of refuge vital for the enjoyment of the public, and the author’s choice to protect some Utah land from oil and gas development. (17:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Elena Krieger, Linda Bilmes, Terry Tempest Williams

REPORTERS: Reid Frazier, Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Pollution from dirty power-plants causes thousands of excess deaths and runs up billions in costs for communities already under stress.

KRIEGER: These are places that have high levels of low-income populations, minority populations, populations with low access to health insurance, high levels of background health burdens and disease.

CURWOOD: The numbers and a possible remedy. Also, large amounts of methane escape from the US gas production system. It’s costly and has dangerous climate impacts.

ZIMMERMAN: If you're not burning the natural gas, and you're releasing sort of pure methane into the atmosphere, the methane has a much higher global warming potential than carbon dioxide on sort of a 25 year time scale.

CURWOOD: America’s air at risk and much more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

America’s Deadly Power Plants

Avon Lake, a coal-fired power plant near Cleveland, has been out of compliance with the Clean Air Act for at least three years. Its particulate pollution is responsible for hundreds of premature deaths, according to PSE Healthy Energy and Nextgen Climate America. (Photo: Ben Stephenson, Wikimedia Commons CC-BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Pollution from power plants in Pennsylvania and Ohio during 2015 led to the early deaths of more than 4,400 people in America, according to a study by the think tank PSE Healthy Energy and NextGen Climate. Residents closest to the plants near Pittsburgh and Cleveland had the highest premature death rates, but particulates and other pollutants from those power plants increased mortality and morbidity as far away as Maryland, New Jersey and Massachusetts. Poor and disadvantaged communities shouldered most of the burden of this environmental risk, and up to $38 billion in health costs and impacts. Joining us now is the lead author of the study, Elena Krieger. She’s the Renewable Energy Program Director at PSE Healthy Energy. Welcome to Living on Earth, Elena.

KRIEGER: Thank you very much for having me.

CURWOOD: So, what exactly did the study find?

The impact of dirty power plants extends far beyond their local environments. Particulate emissions from Pennsylvania plants contribute to health problems and premature deaths as far away as Massachusetts, Virginia, and Michigan. (Photo: Nextgen Climate America)

KRIEGER: So, there are three different components to our study. We looked at demographic and socioeconomic and existing environmental and health burden information on communities living near power plants in Ohio and Pennsylvania. Ohio and Pennsylvania have some of the highest carbon emissions from the power sector in the United States. So, that's part of the reason we looked at the states. We also looked at existing environmental hazards that those plants. So these are things like on-site releases of toxic chemicals, coal ash pits where they get rid of all of the leftover ash after coal combustion, and in the third part we looked at the emissions that come out of these plants, out of the power plant stacks, and particulate matters associated with those emissions which can have health impacts far across the state and well into neighboring states and far beyond.

CURWOOD: So how far can these emissions go?

KRIEGER: We found that the highest impacts are perhaps in the states of Ohio and Pennsylvania, but in the 10 counties that had the highest health impacts from Ohio and Pennsylvania plants combined included counties in Maryland, New York, New Jersey and then you're getting things in Maine and North Carolina.

CURWOOD: So, sounds like Jersey gets a bad rap for bad air is actually...

KRIEGER: [LAUGHS] It's not Jersey's fault. Jersey has actually shut down the vast majority of its coal plants. A lot of pollution is coming in from Pennsylvania and Ohio.

CURWOOD: So, what are the methods of the study? In other words, how do you know that these power plants are causing health effects that result in premature death?

KRIEGER: So, we used an EPA model called COBRA, the Co-Benefits Risk Assessment Model. We took existing historic emissions of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides which are measured at every power plant every hour, and modeled where those pollutants go. There's an underlying atmospheric model that then looks at how those pollutants react in the atmosphere to form particulate matter, and where those pollutants go in relation to population centers. So we see how many people are living in each county and estimate how much particulate matter folks living in those spaces inhale.

Many coal and gas-fired power plants are located in or near low-income and minority communities, which often have high rates of disease and disability and little access to health insurance. Natural gas plants like Brunot Island in Pittsburgh are especially likely to border these areas. (Photo: Jon Dawson, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, I take it that you didn't actually go to each of these counties and look at mortality and morbidity but based this on earlier studies.

KRIEGER: Yes, so the health impact side is based on modeling work, and so we cannot say,“This person specifically had a heart attack because of pollutant emissions at this plant.” What we can say is that we know that high concentrations of particulate matter are associated with a whole range of health impacts leading up to premature death, particularly for vulnerable populations like the elderly and those with underlying diseases. What we didn't calculate actually is we did not look at other pollutants from the plants like ozone, for example. It also forms from nitrogen oxide emissions, and these can also contribute to additional health impacts, so we likely have an underestimate of the impacts of these plants.

CURWOOD: So, there are a number power plants here. Any of them particularly responsible for these deadly emissions?

KRIEGER: Two of the power plants, one in Ohio and one in Pennsylvania, are two of the highest emitters of sulfur dioxide in the country. One of these is Homer City in Indiana County in Pennsylvania which is outside of Pittsburgh. The other one is Avon Lake which is near Cleveland in Ohio. Avon Lake is also situated in a county where concentrations of particulate matter and ozone exceed federal standards and some of the highest asthma rates in the state as well.

CURWOOD: Now, these emissions can travel quite a distance, but I'm thinking that folks living closer to these power plants had more trouble. How correct is that assessment?

KRIEGER: So, if you look at the per capita health impacts, they tend to fall heaviest on the counties containing the plants and downwind from those plants. The majority of the power plants are located in low-income communities. Half of the power plants in Pennsylvania are located within or near communities that are designated as environmental justice areas by the state of Pennsylvania. These are places that have high levels of low income populations, minority populations, populations with low access to health insurance, high levels of background health burdens, and disease. These are particularly vulnerable communities that are most susceptible to some of the burdens of pollution in the first place.

Elena Krieger is Renewable Energy Program Director at Physicians, Scientists, and Engineers Healthy Energy. She holds a PhD in Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering from Princeton University. (Photo: Elena Krieger)

CURWOOD: Now, how specifically would the Clean Power plan that is being advanced by the Obama administration, how might that reduce the health damages that you found?

KRIEGER: The Clean Power plan sets targets for carbon emission reductions for the power sector in United States, which is the highest source of carbon pollution in the country. Each state has its own individual target for carbon emission reductions based on an existing list of gas plants, of coal plants, of whatever is generating electricity in that state. Depending on where you cut carbon, you also have a chance to cut pollution from plants that have high health impacts at the same time or are located near low-income and vulnerable communities at the same time. You're going to get a much higher benefit if you try to reduce carbon emissions at some of these plants have really high rates of, let's say, sulfur dioxide emissions near Cleveland near Pittsburgh rather than at a plant that has much lower emissions of co-pollutants and so what we hope is that this information can be a tool for people to push for regulation, special policies that will actually led to a cleaner, healthier power sector in their state.

CURWOOD: Elena Krieger is Renewable Energy Program Director at Physicians, Scientists, Engineers for Healthy Energy. Thank you so much for taking the time, Elena.

KRIEGER: Thank you so much for having me.

Related links:

- The reports and summaries from PSE Healthy Energy and NextGen Climate America

- The EPA’s page on particulate matter pollution

Beyond the Headlines

Republican Presidential nominee Donald J. Trump vowed to keep American coal miners at work in his nomination acceptance speech Thursday, July 21, 2016. (Photo: Michael Vadon, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Time now to check in with Peter Dykstra, who watched the Republican National Convention in Cleveland from his perch in Conyers, Georgia. Peter is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Hi, Peter, what’s beyond the headlines regarding the nomination of Mr. Trump, and the Republican Party platform?

DYKSTRA: Well hi, Steve, you know, there were if any voices speaking out for the environment at the convention, and some Republicans who still might be inclined to do so stayed away from Cleveland entirely. Of the three Senators who sided with Democrats on the Clean Power Plan, only Susan Collins of Maine was there. Of the 13 GOP Congressmen & women who voted for a resolution last year acknowledging that climate change was real, only five made plans to go to Cleveland, and their absence means that even a moderate voice on these issues had left the building, and if you want some evidence for that, let’s page through the Republican National Committee platform adopted this week in Cleveland.

CURWOOD: The distinguished gentleman from Georgia has the floor.

DYKSTRA: Thank you Mister Host. Let’s start with one thing that defies the partisan divide: The GOP calls for modernizing the electric grid, something that people from all political sides say is a good idea.

CURWOOD: Yeah, but I don’t see anyone rushing to pay for it.

DYKSTRA: Yeah you’re probably right. The GOP platform is opposed to labeling food products containing GMOs. It calls for full steam ahead on exports of oil and natural gas, and it wants the management of most public lands handed over from the Feds to the states. And the platform stops barely short of diving into the climate denial language we’ve heard from Mr. Trump and from his running mate Mike Pence and virtually every one of the other GOP candidates who competed with Trump for the nomination.

CURWOOD: So just what exactly did they say?

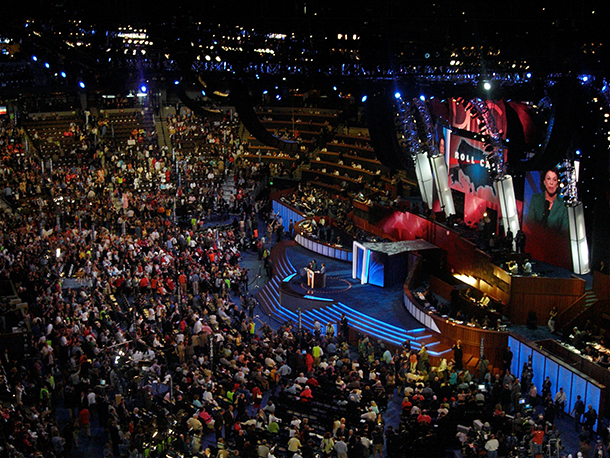

Convention season in this Presidential election year is bringing thousands of delegates to Cleveland, Ohio for the Republican National Convention, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania for the Democratic National Convention. (Photo: Qqqqqq, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, the platform took a slap at the assessment that climate change will be a major global security issue, something that President Obama and the Pentagon have said. But they go as far as many GOP Senators, Congress people, and Presidential candidates who’ve said that climate change is a hoax. The platform also denounces the Kyoto Accord from the 1990’s, last year’s Paris climate agreement, and efforts by the UN to assess the science and pay for climate action. And the GOP pointed out how drought, extreme weather, and wildfires have been wreaking havoc lately, but they made no mention at all that climate change might have something to do with it all.

CURWOOD: Peter, how much attention did climate, environment, and energy get at the Convention itself beyond the platform?

DYKSTRA: Well here’s one. Shelley Moore Capito the West Virginia Senator pretty much blamed President Obama and Hillary Clinton for the 30 year decline of the coal industry. And I was thinking about how hard it would have been to go after job killing regulations after the roll call vote that officially nominated Donald Trump. Y’know, the traditional thing where each state delegation boss brags about their college football team, or how they’re America’s leading producer of bauxite or pecans or hubcaps.

CURWOOD: Yeah, a lot of the states bragged on about how well their economy is going, so it was a little hard to turn around and crucify the “job-killers” on the other side. What were some of the other enviro highlights from the floor speeches?

DYKSTRA: Donald Trump’s family acquitted themselves really well, particularly Donald Junior, who got in a few jabs at EPA and regulation. And of course, potential First Lady Melania Trump delivered an exemplary take on re-use and recycling.

But back to the platform for a minute, since we’re talking about something less than a love-fest for EPA. Donald Trump says he’d like to seriously shrink EPA; the GOP platform plays it a little differently, calling for EPA to be shrunken to a non-partisan Commission like the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and give most of EPA’s enforcement and inspection duties back to state governments.

A Penn State scoreboard touts 'clean coal', a concept that has yet to find a cost effective technology. RNC politicians spoke in favor 'clean coal' at the convention. (Photo: America’s Power, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Uh, how’s that supposed to work?

DYKSTRA: Well, first let’s look at NRC as a role model. Its members are appointed by the President and approved by the Senate. Two of the five Commissioners were appointed by Obama, and one is a holdover from the Bush Administration.

CURWOOD: I got a math problem here. There are supposed to be five. You only named three. How about the other two?

DYKSTRA: What other two? One of the five commission seats has been vacant for eighteen months, because President Obama and the Senate are soooo non-partisan with each other, the fifth seat opened up last month. So I’m not sure that NRC is such a great example of a functioning, non-partisan agency. And in terms of ceding EPA’s duties to state governments, that’s already been done in many places, and it’s not going very well, with factories, sewage plants, and waste dumps going un-inspected for long periods of time. But let’s move on to my bar-none, most favorite environmental thing from this convention and its platform.

CURWOOD: Does we need to offer a listener advisory?

DYKSTRA: Probably not, but listeners please keep safe with the eye-rolls and face palms. A proposed plank in the GOP platform said that coal was “an abundant, reliable, affordable energy source.” But not so fast. Some objected. So Texas delegate David Barton poured coal ash on troubled waters by offering an amendment, which passed by acclamation. The Republican National Committee now endorses coal as an “abundant, clean, affordable, reliable energy source.”

CURWOOD: Hmmm…Hasn’t the Federal government already poured a few billion into “Clean Coal” research with little to show for it?

DYKSTRA: Right.

CURWOOD: So – well, next week, can we talk about the Democrats and their convention, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Absolutely, there’ll be plenty of fodder there as well.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that's EHN dot org, and DailyClimate dot org. Thanks Peter, we’ll talk to you next week.

DYKSTRA: Thanks a lot Steve, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- GOP platform on energy and environment

- Mother Jones: “The GOP Convention Is Way Too Hot for Republicans who Want to Solve Climate Change”

- The 2016 full Republican Party platform

[MUSIC: Harry Allen: “America the Beautiful” from Tenors Anyone (Slider Music 1997)]

CURWOOD: Just ahead...news about the evolution of walking fish. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Harry Allen: “America the Beautiful” from Tenors Anyone (Slider Music 1997)]

High Tech Hunt for Methane Leaks

The shale oil boom has precipitated a growing network of natural gas pipelines in the U.S. – but along with that network comes more leaks. (Photo: Tim Evanson, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. There are thousands of gas wells in the Marcellus Shale of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia, and a growing number of pipelines moving that gas around the Northeast. But the infrastructure leaks the potent greenhouse gas methane at all stages of production and delivery. The Allegheny Front’s Reid Frazier tagged along with a team of scientists trying to figure out just how much.

ZIMMERMAN: There’s actually a blue line with the green line, but you can’t even see it anymore.

FRAZIER: Naomi Zimmerman is checking a computer screen inside a white van that looks like it came straight from an episode of Stormchasers. Zimmerman is leading a team of researchers from Carnegie Mellon University looking for methane here in the rolling hills of northeastern Pennsylvania. Computer monitors and expensive sensors are mounted inside the team’s van, wind and weather probes on the outside. All told, there’s a half million dollars of equipment on the rig. To start her day, Zimmerman must first make sure the team’s monitors are calibrated correctly. On a screen mounted to the dashboard. Zimmerman reads off her levels.

ZIMMERMAN: We’re seeing readings of 0, 0.16, -0.1, .1, 1.4. That’s approximately zero. Good enough for our standards.

Mobile labs help scientists detect methane leaks coming from Pennsylvania’s natural gas pipelines. (Photo: Reid Frazier)

FRAZIER: With their rig checked out, the team is ready to roll. A few years ago, northeastern Pennsylvania was one of the hottest drilling spots in the country. Now, most of the rigs are gone. But there are thousands of wells already drilled. And the hills and dairy farms around the region are criss-crossed with pipelines, compressor stations and other infrastructure siphoning gas away from those wells. The team’s first stop is about half an hour away, next to a pipeline tucked onto the back edges of a local farm. They park their van, and turn on the equipment. A minute later, scientists Aja Ellis and Mark Omara see a spike on the levels in their computer screen.

ELLIS: I think we have a pipeline leak...I think there’s a pipeline that runs across. You can see how the concentration’s going up, ethane and methane. We know that it’s holy...wow....that is super big...that is super exciting.

FRAZIER: The team is picking up about 1.2 parts per million of methane, or about 12 times the amount they would normally see coming off of a well pad. Then, they see the levels go even higher.

ELLIS: Whoa.

ZIMMERMAN: It just went up to 9 per million. Wow. Wow.

ELLIS: So, this is a leaky pipeline right here…

Carnegie Mellon researcher Aja Ellis monitors air emissions near a Marcellus Shale gas well in Wyoming County, Pennsylvania. (Photo: Reid Frazier)

FRAZIER: These readings could help Zimmerman and other researchers answer what’s become an important question. How much natural gas is leaking into the atmosphere? One of the benefits of natural gas is that it when it burns it produces far less carbon dioxide than coal, a fuel that gas is rapidly replacing as a source for electricity. So if you’re burning gas instead of coal, that’s good from a climate change perspective. But, there’s a rub. Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas. So...

ZIMMERMAN: If you're not burning the natural gas, and you're releasing sort of pure methane into the atmosphere...the methane has a much higher global warming potential than carbon dioxide... on sort of a 25 year time scale.

FRAZIER: Zimmerman’s colleagues at Carnegie Mellon have found the EPA has been underestimating methane leak rates for years. But they’re still not sure exactly how much of it is escaping the country’s oil and gas system. Why can’t they figure this out? One reason is the sheer number of places where gas can escape. Mark Boling is a vice president for Southwestern Energy, one of Pennsylvania’s largest natural gas producers.

Hydraulic fracturing for natural gas has sparked concerns about water contamination. Since gas travels upwards through shattered rock, gas can sometimes rise through natural springs to the surface. (Photo: J.B. Pribanic / Public Herald, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BOLING: Unlike other areas of power plant emissions, CO2 from power plants. We're not talking about one big facility that you have one stack and say,“there's your source it's coming out there.”

FRAZIER: Instead each step of the natural gas network contains hundreds of places where gas could escape. Boling’s company cooperated with the Environmental Defense Fund on several studies to better understand methane pollution. He says spending money on equipment that can prevent methane leaks is good business for his company.

BOLING: That methane we can save from going up into the air and going into a pipeline, whatever we get for that will help defray the cost.

FRAZIER: The EPA and several states, including Colorado and Pennsylvania, have begun implementing methane regulations on the oil and gas industry. Boling resists these types of regulations because they prescribe equipment for companies to use that may not be necessary or effective.

BOLING: You're basically telling them,“I have 100 different sources, 20 are the problem, but I want you to replace all 100.”

FRAZIER: He says it’s better to let companies decide how to reduce their own emissions. And there’s evidence that companies are starting to take methane pollution seriously.

COUNTDOWN: ...Five, four, three, two…

The Hunt for Methane Leaks Goes High-Tech from The Allegheny Front on Vimeo.

FRAZIER: That’s audio from a satellite launch in India this June. Aboard the rocket was a satellite called ‘Clair’, equipped with high resolution methane sensors. Stephane Germain is CEO of GHG SAT, the Montreal-based company that launched the satellite. His clients include ExxonMobil and Shell. Germain says these companies can make money with this data, because in Canada they’re already subject to a carbon pricing system.

GERMAIN: Industrial operators would be financially motivated to better understand their emissions. So that they can control them and ultimately reduce them. Because really what they’re doing at that point is reducing their own financial risk.

FRAZIER: Using satellites to measure greenhouse gases is a technique NASA has used for years, but with improving sensors, they may become more important in the search for methane leaks. Daniel Jacob is a Harvard climate scientist who uses satellites to measure methane in the atmosphere above the United States. Jacob says satellites could be an early warning system to help on-the-ground teams find and fix leaks.

JACOB: Satellites can provide you with detection. They can tell you - Aha - you got a hot spot here. And then once you figured out from space you have a hotspot then you can dispatch ground-based instruments or maybe low flying aircraft to figure out where this methane is coming from.

FRAZIER: Jacob’s last paper used satellite data with a resolution of 10 square kilometers. His current project is using Clair, which has a resolution of just 50 meters. Clair is scheduled to start sending methane readings back to Earth this fall. I'm Reid Frazier.

CURWOOD: Reid reports for the Pennsylvania public radio program, the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Read the story on The Allegheny Front

- Watch a short video about methane leak detection from The Allegheny Front

- Read Bill McKibben’s article: “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Chemistry”

[MUSIC: Glen Campbell: “Classical Gas (Live)” from The Legacy (Capitol Nashville 2006]

Emerging Science Note: Walking Fish

A mudskipper half-submerged (Photo: missresincup, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: In a minute, plumbing the depth of support for America’s national parks, but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

LYMAN: The mudskipper is a funny looking fish with bulging eyes, and foot-like fins that it uses to hop and crawl around on the slippery flats of the mangrove swamps. It’s at home both on land and in water, and if you’ve ever seen one, you can easily imagine the day in prehistory when it first developed this adaptation and crawled out of the sea.

Now Australian researchers say that the evolution of amphibious fish – fish that spend time in and out of water – is more common than we thought. The challenges of breathing air and moving about on land might seem daunting for fish, but biologists from the University of New South Wales report that 130 species and 33 fish families have managed to do it. And species from four families of fish, including gobies, blennies, and eels can spend hours or even days out of water.

Amphibious fish exist in all climate regions, and in both fresh and sea water, though they are far more common in saltwater habitats, particularly in the intertidal zone. Intertidal areas vary widely in conditions such as water temperature and the amount of dissolved oxygen, and daily tide cycles expose marine organisms there, including fish, to both sea and land conditions.

The researchers say that water temperatures in the intertidal zone often increase as the tide recedes, particularly in pools at low tide. Since increased temperatures reduce the amount of oxygen dissolved in water, they believe that could serve as a stimulus for fish to leave the water – and head for more hospitable habitat on the land. That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Related links:

- Read the study: “Repeated evolution of amphibious behavior in fish and its implications for the colonization of novel environments”

- About the mudskipper

- Watch the mudskipper episode from BBC’s “Life” series

The Value of National Parks

The view from Glacier Point in Yosemite National Park. As of June 30th of this year, attendance was up by 3 million from that time last year. (Photo: Taylor Davis, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: How much would taxpayers like to spend to support America’s National Parks? To answer that question Linda Bilmes of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, along with colleagues from Colorado State University carefully surveyed taxpayers in a recent study. And according to their research, the public would pay more than $90 billion a year to preserve and protect iconic places from Acadia to Zion. Yet the US National Park system currently receives less than $3 billion a year from Congress and suffers from a multi-billion dollar backlog of corroded or broken infrastructure. Professor Linda Bilmes is also a former US Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Administration and Budget, and we joined her in her office at Harvard. Welcome to the Living on Earth.

BILMES: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: What prompted you to do this study?

BILMES: I was lucky enough to serve on the Second Century Commission. It was a group of prominent Americans including Sandra Day O'Connor. Sylvia Earle, Rita Colwell, James McPherson of Princeton, and a number of senators and congressmen, and we were thinking about how to protect the National Parks over the next 100 years. And one of the conclusions that we reached was that the financial picture was not sustainable given the way the National Parks are funded at the moment. So in order to begin thinking about creating a more sustainable financial structure for the national parks, we needed to establish a baseline for what the parks were actually worth, and actually no one had done this before. So this led me to begin thinking about how one could estimate the total economic value of the National Park Service and to do it in time for the centennial.

An assessment of the economic value of the National parks that was published this month puts the worth of America’s national parks at $92 billion per year. (Photo: Lorne Sykora, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now some would say that our National Parks are priceless, you can't put a price on something like the Grand Canyon or the Grand Teton. So what you're talking about, I gather, is the capital value of this, as an asset that America should look at. It's not really for sale.

BILMES: No, it's not for sale, but you raise a very important point, which is how do we actually value a priceless asset? And economist do this by asking what one would pay not to lose that asset, so in the conservation field we are particularly at a disadvantage because there's a very robust, well-established accounting procedure for figuring out what the value is of constructing a building, for example, but there's no agreed-on methodology for how one accounts for not constructing a building, for protecting the land.

CURWOOD: So how do you solve this dilemma?

BILMES: Well, we used a methodology similar to that used by civilian US agencies, such as the Food and Drug Administration and OSHA, and we conducted an economic survey. So I want to stress that this was not a poll, but an economic survey in which we went out and asked households what they would pay to not lose the National Park Service units and programs. Surveys were sent out to households across the country, and with different amounts of money on them, and so we could figure out that at the higher levels of payment fewer people would be willing to pay, even if they love the parks, and at the lower levels, for example, $10, $15, practically everyone is willing to pay that much in higher taxes. And we're not advocating higher taxes for parks, but this was a way of getting at what the value was that the public attributes to protecting the parks and park programs.

CURWOOD: So, some 90, 95 percent in your study said that these parks are important. I mean, what else are we unanimous about as Americans these days?

Linda Bilmes is a Senior Lecturer in public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. (Photo: Diana Bowen/NPS)

BILMES: Well, I think that there are very few entities and public assets that command this kind of respect, and really love, that we heard in this survey. But I think beyond that what we felt we were trying to do was to understand how people who didn't necessarily visit the parks felt about the parks and the programs because we'll already knew that those visit the parks typically love them and many surveys show that a lot of people like the parks very much. They think they are wonderful, but the question was, could we quantify the fact that I might place a value on protecting Gettysburg or protecting Ellis Island or protecting the Grand Canyon, even if I don't visit, that that still means something to me, and that's where we were amazed to find that the value was $92 billion which is more than 30 times what the annual appropriation for the parks is.

CURWOOD: So what is being spent on the park service now and what does it need?

BILMES: Well, the Park Service currently gets an annual appropriation of about $2.5 billion a year and the Park Service budget has actually been declining over the past 20 years. In fact it's 15 percent below, in today's dollars, what it was in 2001. In addition, the park service has a maintenance backlog of about $12 billion, and that is a backlog of infrastructure projects, for example, campgrounds and trails and bridges and roads and things like that. So not only is the annual appropriation insufficient to cover its needs, but it has been completely unable to finance its long-term infrastructural, maintenance needs. So, in other words, the National Parks as they're currently funded are decaying because of the fact that we're not keeping them up.

CURWOOD: Yet the public is willing to spend much, much more, almost 30 times more then what the annual appropriation is. So why are we in this state?

BILMES: Well, I would say that there are two major points around the National Park funding. The first of all, this is the centennial of the National Parks, and our study shows that the public places a very high value on the parks and so we are urging Congress to give a birthday present of some amount of money to begin tackling the maintenance backlog for the parks. But when you think about the broader issue which is that the public is conservatively valuing the parks at 92 billion, and the amount we spend on the parks, even including fees and so forth is below $3 billion, there's no way that the government is going to be able to make up that huge gap.

So this is where private philanthropy comes in, and there is a National Park Foundation, which has operated for a number years. The private philanthropy has played a role in shoring up many individual parks. However, we don't have an overall philanthropic, long-term perpetuity funding structure for the Parks. So I've been urging for some time that we set up an endowment for the Parks which is a funding mechanism that Harvard University has, for example, and many museums and hospitals and others that have a kind of forever mission because the mission of the parks is to protect these special places, unimpaired forever and the only way that they can do that is if they have an endowment which they can tap into to try and make the investments and keep up with the long-term maintenance, repair, and stewardship which is their mission.

CURWOOD: Your favorite park or parks?

BILMES: You know, I have to say that I grew up in San Mateo, California. and the Golden Gate National Recreation Area is probably my favorite because I know it best. It stretches along the coast of San Francisco, is a fantastic place, and it also does an enormous amount of educational efforts. I'm also very, very partial to Yosemite and to Yellowstone in the winter. Yellowstone Park, when it's empty in February and it's cold, is like no place on the planet.

CURWOOD: Linda Bilmes is the Daniel Patrick Moynihan Senior Lecturer in Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. Thanks so much for taking the time.

BILMES: Thank you so much for having me.

Related links:

- Read the paper: “Total Economic Valuation of the National Park Service Lands and Programs”

- Also by Linda Bilmes, et. al: “Carbon Sequestration in the U.S. National Parks: A Value Beyond Visitation”

- Linda Bilmes Faculty Profile

- National Park Service Centennial

- Annual Park Budget Justifications

[MUSIC: Charanga Cakewalk: “Gloria” from Chicano Zen (Triloka Records 2006)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...soaring wild places can inspire soaring prose. One of America’s favorite nature writers is just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Rob Curto, “Biruta,” Piano De Fole, Jacob do Bandolim, released by Rob Curto (not on a major label)]

The Hour of Land

A pair of twin buttes gives the Bears Ears area its name. (Photo: brewbooks, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Terry Tempest Williams is one of the most celebrated of current writers about the American West, and she has a new book that has come out during the 100th year of the US National Park System. The volume is called "The Hour of Land", but it is as much, if not more, about people who visit the National Parks as the iconic landscapes themselves. Terry is on the line now from her Wyoming home near Grand Teton National Park. Terry, welcome to Living on Earth.

WILLIAMS: Thank you so much, Steve. It's a joy and a pleasure.

CURWOOD: Why did you set out to write this book?

WILLIAMS: I love the National Parks, and growing up in Utah, we're surrounded by National Parks and Monuments. Zion, Bryce, Canyon Lands, Arches, and Capitol Reef.,so, for a child growing up it was our backyard and it remains so now. And the book is called "The Hour of Land" and yet it's about people.

Smoke filled the valleys of Montana’s Glacier National Park in 2003. The Tempest family nearly perished in the fire when it roared around the lodge where they took shelter. (Photo: Jan Tik, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

I'll never forget my grandfather, Jack Tempest. I was in college and he called me and said “I’d like to talk to you,” and that was very rare. He was a very stoic, private man, and I immediately went over. We sat down and he said, "I want you to tell me three experiences that you’ve had in widerness. And I'm listening." And I said, "OK, the time when our family was walking down the Zion Narrows."

“OK, one. And tell me about the Zion Narrows."

"Well, Dad was leading. Mother was behind him, and Steve and I and all the boys, we were following. It was dawn, just first light and I've never felt so connected."

He said, "OK, give me the next time."

"It was in the Tetons. We were on the Teton Crest Trail. Again, with my father and cousins."

And it went on like that, and then he said, "Stop, do you recognize that every single experience you've told me had people, and people that you love?"

And that was a teaching moment for me, Steve, and I realized we're not separate. Whenever we're in the land, we are part of the land.

CURWOOD: You’re speaking to us right at the edge of the Grand Teton National Park. Tell me the story of your family’s experiences with Grand Teton near Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell visited ancient cliff dwellings in McCloyd Canyon near Blanding, Utah during her July 2016 trip to the proposed Bears Ears National Monument area. (Photo: Scott G Winerton, Deseret News / U.S. Department of the Interior, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

WILLIAMS: I call it “My Mother Park.” My first memories here, of drinking water with cupped hands at Hidden Falls and Cascade Canyon; across from Jenny Lake my mother on one side, my grandmother on the other, and hearing them say, “Drink deeply, Terry. This is the source.” I’ve never forgotten that. Five generations standing on the side of the road listening to the elk bugle under a full moon; one of them being my great aunt who was losing her hearing and she said.“When you hear the elk – I can’t hear it -- but just raise your hands, because I remember it.” The history is long and deep and generational. It’s a memory palace. Relatives’ashes are scattered here, and my father is here now, as am I, so it’s a migratory path for our family, and I think many families have these familial memories with particular National Parks.

CURWOOD: Those places that are so familiar to you, you know, there's a spiritual aspect to some of those places. I remember going to Capitol Reef with a group of tough environmental journalists going out for a hike, and as we were coming up through part of the park where there is this big overhang, almost looked like an amphitheater of some kind, everybody in the group spread out so that we were all by ourselves out of the earshot of the footfalls, and it was if we went into some sort of meditation getting out of the newsroom and all of that. How common do you think it is for people to feel that there's something spiritual in a wild place, National Park or not?

WILLIAMS: I think any time that we enter a National Park, we meet the miraculous. I do think it's a spiritual experience, especially now. You know, everyone now is so tied into technology and their mobile devices, and I think to go into a National Park and feel that quiet, that space, that overwhelming sense of “other,” it drops me to my knees. You know, whether it's the vastness of the Grand Canyon, shimmering waters in the sawgrass of the Everglades or that rocky edge of Maine in Acadia National Park, for me it is a deeply spiritual experience.

A distinctive geologic formation called Comb Ridge would be included in the proposed Bears Ears National Monument. The ridge is 21 miles long and composed of Navajo Sandstone rock. (Photo: Doc Searls, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, these National Parks according to this book are been dangerous for you. Tell me the story of how you and your family almost perished in Glacier National Park?

WILLIAMS: Maybe it's our family name, Tempest, I don't know, (Curwood laughs.) but it was my father's 70th birthday. He wanted to repeat a trip that we had taken 10, 15 years before, hiking to the Granite Park chalet. We did that. I think there were 16 of us, three generations, and it was beautiful, but then suddenly we realized that this was the season of fire. There was a perfect storm brewing, literally, and what looked like fires from afar suddenly became perilously close. My eyelashes were singed. The flames were so close, the heat was so intense. We had to all gather inside the Granite Park chalet in a circle on the floor with the children in the center and we were told by the fire ranger who was helicoptered in that the fire was going to roar over us that we would bear down, hold our breath. It was going to be uncomfortable. The windows were going to blow out, but hopefully the fire would roar past us. Miraculously, the fire split around the stone building and raced up a swift current pass, and we survived.

CURWOOD: And what did you take away from that experience?

WILLIAMS: Awe. Fear. Gratitude. Family. You know, when we hiked out in single file the next morning with the ranger in front and a ranger in back, the grizzly bears were walking right below us. There's always risks, but I think it reminds us that we're vulnerable. We're not the only species that lives and breathes and dreams on this planet.

CURWOOD: Terry, why did you call your book "The Hour of Land"?

WILLIAMS: Would you believe me if I told you, it came to me in a dream?

CURWOOD: Of course. Why not?

WILLIAMS: I do a lot of my ... I call it “night work,” the work that means most to me as a writer and it's a question that I set to my night mind, and when I wake up it's usually there. And "The Hour of Land" came that way.

Some national parks, including Gettysburg National Military Park in Pennsylvania, are primarily dedicated to educating visitors about historical events. (Photo: Jen Goellnitz, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

I believe that this is the hour of land, especially now when we on so many levels have forgotten the source, that we are tied to the land, to the earth, and never has that mattered more than now, whether it's the violence that we're seeing on our streets, be it in Dallas or Baton Rouge or Minnesota, or whether it's climate and rising seas. This book is about listening, whether we're listening to our genealogy, whether we're listening to Sandhill Cranes, whether we're listening to one another. I think this is what is getting lost. We have become a people of opinions, and we barely speak to those who have different opinions. And our National Parks open us to those different kinds of conversations.

CURWOOD: And how important is it to listen to the land?

WILLIAMS: For me, personally it's essential. In June, I was able to go to Yosemite National Park and listen to President Obama speak, and I was undone by his joy, and particularly there was a sense of relief. You know, he arrived with his family in the aftermath of the mass murders at Orlando and Yosemite Falls was in the background, and he turned and looked over his shoulder and he just said, "This, this is what reminds us that we belong to something bigger than ourselves." He broke from the script that had been prepared for him, and he talked about how when he was 11 years old, his mother took him to the mainland for the first time, and they went to Yosemite. And he spoke passionately about seeing a moose for the first time standing in a pond, of turning, and there was a meadow of deer and turning again and seeing a female grizzly with cubs. And he turned to the audience and he said, "It changes you. It changes me, and that's why I want to see more National Parks and Monuments and why I'm so determined to see that people of color, people that live very close to Yosemite who have never been here, have that opportunity."

CURWOOD: Terry, you know, in this country, wilderness is often associated with privilege. What do you say to folks that say that National Parks are just preserving wild spaces for the rich and the privileged?

WILLIAMS: I understand their point of view, but I don't agree with it. You know, I talk about how our National Parks in this country are not, perhaps, our best idea as well, as Wallace Stegner said, whom I love, but an evolving idea, and that I believe. And nowhere is that more prevalent than in Utah right now. Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell is coming to Utah in Bluff, and she's meeting with the tribal leaders of the Ute, the Navajo, the Hopi, the Zuni, over 25 tribes in the Colorado Plateau to talk about their desire and their proposal to create the Bears Ears National Monument. Now that is not for the rich and privileged. That is to secure and to protect their cultural ways of life. Their ancestors' bones are buried there. Their ceremonies are performed there. Their medicines are found there. And I'm hoping that in this evolutionary spirit, Secretary of Interior Jewell and President Obama, certainly, will see the importance of this and create a National Monument in Utah adjacent to Canyonlands in Bears Ears as a bow to the tribes, as a moment of peace in very turbulent times, especially with race in this country.

Terry Tempest Williams wrote about the desolation of Big Bend National Park in The Hour of Land. The Texas national park remains one of the least visited in the U.S. (Photo: Dave Hensley, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: We're recording this on the 11th of July. The US House of Representatives is expected to vote sometime in the near future on a proposal that would exempt some 48 counties, primarily in the west, from that Monument creation law and the counties will be exempted from the Antiquities Act which can be used to create, essentially, the equivalent of a National Park - would hit the territory of Bears Ears. So what do you make of this move in Congress by the Republican side to block efforts to create the Bears Ears? It also would throw a roadblock in front of the creation of a national monument in Maine and elsewhere.

WILLIAMS: You know, this is an old story. When they created Grand Teton National Park and Monument, they did block any more use of the 1906 Antiquities Act in the state of Wyoming. When Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument was made in 1996 in Utah, there was outcry among a certain part of the state. Now, it's a huge engine for economic growth. People say that public lands, our national parks are elitist, but in reality, they are our commons. They belong to all of us.

CURWOOD: Terry, not so long ago, you and your husband, Brooke, went on a spending spree. You bought yourself an oil and gas lease on federal lands there in Utah. But obviously, you have no plans to develop these particular resources, although, as I do understand it, in the past the Tempest family has been in the pipeline business. Why did you buy this lease, and what do you plan to do with it?

WILLIAMS: You know, it's a complicated story, Steve. It's true. Our family business, four generations, lays pipe, whether it's natural gas, water lines, or sewage. My family, my brothers, my father, my uncle, my great grandfather, have dug those trenches. So they're not in the oil business per se, but they create the pipe that services the communities. So you can understand that when Brooke and I chose to purchase two oil and gas leases, my father was not thrilled because we benefited from that business. But I think it's wrong, what's happening on our public lands with oil and gas development. If you come out to Utah or anywhere in the interior west, from an aerial point of view, from a raven's point of view, it looks like an exposed nervous system. There's so many roads, drill rigs, and fracking going on, it breaks your heart, and if the American people knew that our public commons were being leased for a dollar $1.50 an acre, I think they would be as outraged as we are, and I think now with climate change, climate justice, we have to change our ways, and this was an act that Brooke and I felt would contribute to a different kind of conversation.

CURWOOD: And Brooke is your husband, of course. What will you do with it now?

Terry Tempest Williams is the author of The Hour of Land, Refuge, and ten other books. (Photo: Louis Gakumba, courtesy of Terry Tempest Williams)

WILLIAMS: Well, the Bureau of Land Management has not given us our leases yet that we paid for, and it's now going on six months. The oil and gas companies that also bought leases, they were given their leases immediately, and, truth be told, they have no intention of drilling on those lands either, maybe for different reasons. They're not going to drill on those lands until the price of oil goes up. We've been very public saying, “We don't want to drill on these lands until science can so us that the fossil fuels are more above land than below given the costs of climate.” We were just out on the lands, and they are just absolutely stunning, I have to tell you. We remain hopeful. We are in compliance with the law even as we are pushing the law.

You know, these kinds of actions are not without their costs, but what is the cost if we choose to do nothing? I think each of us, in our own way, in the places we call home, can think about what actions can we participate in that might make a difference in terms of our own sense of community, especially given climate change, especially given public lands and the threats that they're under, especially given the kind of violence that we're seen all over this country. I think we're hurting and we've got to find ways to heal ourselves and our communities.

CURWOOD: Looking ahead, Terry, what's next in these times, and what's next for you?

WILLIAMS: I don't know and that's an honest answer. I resigned from my job at the University of Utah, from the very program that I helped create, the Environmental Humanities Graduate program. I'm sure that the purchasing of the oil and gas leases had something to do with that though I will never know.

CURWOOD: Wait. You said you resigned, but sounds like you got fired.

WILLIAMS: You know, I was politely told that I would longer be teaching there anymore, without going into all the details, and I fought it until I recognized a straight jacket when I see it. So I actually don't know what's next. I'm hoping that the BLM will give us our leases, and I would love to see what we might do there, in learning more about the fossil fuel industry and what our options are if we're concerned not with profit but planetary health and energy, a different kind of energy, an energy that could fuel a different kind of consciousness. I hope I can continue to teach, and I hope I can continue to write this. But at this point I'm really more concerned about, how do we behave as citizens in this country, in a country that feels so at odds with itself? And it goes back to our public lands, our National Parks. I believe they’re breeding spaces in a country where we are increasingly holding our breath.

CURWOOD: Terry, before you go would you would you mind reading one of your favorite passages out of your book?

WILLIAMS: Of course.

“We the people have made mistakes. We've made mistakes in our relationships with those who came before us and the land that holds their histories. We've made mistakes in how we have managed and misunderstood the wild, but after spending a lifetime immersed in our National Parks, I believe we are slowly learning what it means to offer our reverence and respect to the closest thing we as American citizens have to sacred lands.”

CURWOOD: Terry Tempest Williams' book is called "The Hour of Land". Thank you so much for taking this time with us today, Terry.

WILLIAMS: Thank you so much, Steve. I so appreciate the depth and rigor of your questions.

Related links:

- Terry Tempest Williams’ author website

- High Country News: “Emotions run high over monument designation in Utah”

- The Public Lands Initiative, a bill introduced as a counter to the Bears Ears National Monument

- Bears Ears Coalition

- Author Andrea Wulf reviews ‘The Hour of Land’ for the New York Times

[MUSIC: Madredeus: “Concertino – Allegro” from O Espirito Da Paz (Metro Blue 1995)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is holding a special symposium on our oceans and our future, and you are invited. Join me, Blue Planet champion Carl Safina and UMass Boston ocean law and management expert John Duff Friday afternoon on August 12th on Nantucket Island. Details are on our website at LOE.org, or call 617-287-4122 for more information.

[MUSIC: Madredeus: “Concertino – Allegro” from O Espirito Da Paz (Metro Blue 1995)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Anica Green, Jay Feinstein, Emmett Fitzgerald, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Charlotte Rutty, Adelaide Chen, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on Facebook - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered, by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth