August 26, 2016

Air Date: August 26, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Losing Frozen Earth Could Cook the Planet

View the page for this story

As temperatures increase globally, thawing permafrost starts to release large amounts of carbon dioxide and methane, which, in turn, raise global temperatures. Woods Hole Research Center researcher Susan Natali tells host Steve Curwood about new measurements of the possible carbon loss, and how this positive feedback loop could have very negative consequences. (06:45)

U.S. Methane Emissions Drastically Underestimated

View the page for this story

Measuring methane emissions is tough, as the gas escapes from wetlands and landfills as well as from oil and gas drilling and pipelines. Now, a team of scientists using both satellite data and ground observations has found a better way to calculate the release of this powerful global warming gas. Daniel Jacob, Harvard professor of Atmospheric Chemistry and Environmental Engineering, tells host Steve Curwood their study suggests much more methane is escaping than previously estimated, and the US could be responsible for up to 60 percent of the extra. (06:50)

Turning up the Heat on Frigid Offices

/ Lou BlouinView the page for this story

To combat summer’s hot and sultry weather, many US office buildings crank up the air-conditioning. But this sparks conflicts, as men feel comfortable but women shiver and don fleeces. Lou Blouin of the Allegheny Front reports on how these arctic offices became ubiquitous, and Jennifer Amann of the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy tells host Steve Curwood how much could be saved if they turned the thermostat up a few degrees. (09:30)

Better Office Air Makes For Better Thinking

View the page for this story

Architects have long focused on ways to seal buildings up and make them more energy efficient, but new research demonstrates that good ventilation can be important for our cognitive abilities. Steve Curwood speaks with Harvard School of Public Health professor Joe Allen about the new study that documents the details. (09:20)

Pawpaw: America's Forgotten Fruit

View the page for this story

The largest edible fruit native to the U.S. is unknown to most, yet the pawpaw has earned a loyal following among those who are familiar with it. A new book peers into the pawpaw’s storied past, how its popularity has grown today, and why it’s not a staple in the produce aisle. Writer Andrew Moore tells host Steve Curwood about his mission to find the human story in this forgotten fruit. (13:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Sue Natali, Daniel Jacob, Jennifer Amman, Joe Allen, Andrew Moore

Reporters: Lou Blouin

CURWOOD: From PRI – it’s an encore edition of Living on Earth.

(THEME)

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The thawing of the tundra could cook the planet:

NATALI: Our current estimate is that there's about fifteen hundred billion tons of carbon in permafrost. If all of the carbon in permafrost was released into the atmosphere, at that point, this is not going to be a habitable planet for humans.

CURWOOD: We might need a new ice age to save us. Also the battle of the sexes in the summertime office. Women often say the place is freezing and they need a sweater; men tend to say it’s comfortable.

HEDGES: One of the ironies is that when you look at the sales of personal heaters, the peak months are July and August—which is crazy. It means the company is paying money to over-cool the air, and then you’ve people who are actually trying to warm the environment up.

CURWOOD: The air-conditioning wars – and their cost – that and more this week, on Living on Earth - Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In a Beautiful Place Out in the Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Losing Frozen Earth Could Cook the Planet

As much as 70% of the surface permafrost in the northern hemisphere may be gone by the end of this century. (Photo: Awing88, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts in Boston and PRI, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The thawing of the permafrost in the far north is part of ‘growing irreversible feedbacks from the poles to Mount Everest,’ and we are ‘reaching thresholds where only a new ice age reverses impacts.’ That’s the message scientists have been giving to climate negotiators -- that we are at risk of slipping into runaway global warming. Sue Natali of the Woods Hole Research Center in Massachusetts, was part of the team whose alarming projections suggest a ‘permafrost carbon feedback.’ She joins us on the line now – welcome to Living on Earth!

NATALI: Thank you very much. It’s great to be here.

CURWOOD: So, first of all, what's permafrost?

NATALI: Permafrost is perennially frozen ground. It's ground that remains frozen for two or more consecutive years. In some areas, permafrost has been frozen for up to 40,000 years. Permafrost can comprise any material that's in the ground that's below zero degrees Celsius, so it can contain rocks, frozen soil, organic material, so that you can find whole plant parts or trees or tree roots; you can find frozen bones.

Melting permafrost can create thaw ponds like those above, near Hudson Bay. (Photo: Steve Jurvetson, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: What happens when permafrost starts to thaw?

NATALI: So one of the things that happens when permafrost thaws is you can get ground collapse, or ground subsidence, and the reason for that is because permafrost contains ice. When the ice melts, the ground can collapse. The other thing that can happen is if permafrost completely thaws, so that you get a breach, total breach in the permafrost layer, you can get drainage of groundwater and this can lead to drying. One of the things that we're seeing in boreal and Arctic regions is an increase in fire. If the soil dries, this may further amplify this increased fire frequency.

CURWOOD: So how does permafrost affect the global climate?

NATALI: Permafrost thaw affects global climate because there's currently a vast storage of carbon that's frozen in permafrost. 1:29 So our current estimate is that there's about 1,500 billion tons of carbon in permafrost. That carbon is frozen. It's in the form of organic matter, so when the permafrost thaws, microbes decompose or eat that organic matter, and just as we respire carbon dioxide, so do microbes. So microbes release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and they also release methane. And methane is important because it's a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

Permafrost currently comprises about 25% of the Northern Hemisphere land surface. (Map created by Greg Fiske. Data from Brown, et al. 2001 NSIDC)

CURWOOD: So why is it thawing?

NATALI: Permafrost is thawing as a result of climate change. In the Arctic, the air temperatures are warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet, and this is projected to continue into the coming decades and centuries.

CURWOOD: How much permafrost is there?

NATALI: Permafrost regions comprise about 25% of the northern hemisphere land area.

CURWOOD: And how much of it do we expect to lose?

NATALI: Our current projections are that we can expect to see a 30 to 70% decline in near surface permafrost, and that range in large part is driven by our different emission scenarios. So under low emissions we can expect about a 30% decline in permafrost. But under our current emissions scenario, it’s up to 70%.

Above, Natali carries a carbon dioxide flux chamber, used for measuring CO2 uptake by plants and release from plants and soils. (Photo: Christy Lynch Designs)

CURWOOD: What are we talking about in terms of carbon winding up in the atmosphere here? How might this affect the whole planet?

NATALI: Right. So if 70% of our permafrost thaws, our current estimate is that by the end of this century, we can expect to lose 130 to 160 billion tons of carbon from permafrost as a result of thaw. So to put that in perspective, in 2013 the United States emitted 1.4 billion tons of carbon from fossil fuel combustion and cement production. Greenhouse gas released from permafrost regions is on par with emissions from the United States.

CURWOOD: So how does the carbon in the permafrost compare to other sources, other places, where carbon is on the planet?

NATALI: The amount of carbon in permafrost is almost twice as much carbon as is currently contained in the atmosphere. There's three times more carbon stored in permafrost than is contained in the world's forest biomass on a global scale, and the amount of carbon in permafrost is on par with our current estimates of fossil fuel reserves. And the thing that I think is important about these numbers is that when we think about the world's forests and deforestation, in theory, we can control deforestation and land use change. We can control our fossil fuel emissions, but once permafrost starts to thaw, we cannot control how much carbon dioxide and methane is released by microbes into the atmosphere from thawing permafrost.

CURWOOD: How much is the release of carbon from permafrost factored into the current climate negotiations?

NATALI: Permafrost carbon emissions were not included in the last IPCC report, but scientists are working to incorporate permafrost carbon release into Earth system models, so that our next climate projections can include this additional carbon loss as a result of permafrost thaw.

CURWOOD: So you're not a climate modeler, Dr. Natali, but if you factor in permafrost thaw to climate projections, how does that change things do you think?

Dr. Susan Natali researches the effects of climate change on terrestrial ecosystems at Woods Hole Research Center in Falmouth, MA. (Photo: Christy Lynch Designs)

NATALI: Well, international negotiators had set two degrees Celsius as an upper limit, an acceptable level of climate change. To remain below the two degrees Celsius target, our total emissions are limited to 790 gigatons, or billion tons, of carbon. We've already released about 500, so that leaves us a little under 300 billion tons. We can expect 150 of that to be taken up as a result of permafrost thaw. So this makes it very challenging for us to stay below this two degrees Celsius. Even under our lowest emissions scenario, we're pretty close to 2.2 degrees Celsius. We're about a quarter of a degree away from that. Factoring in permafrost emissions is extremely urgent, and what this means is this puts greater urgency on reducing our fossil fuel emissions.

CURWOOD: So, alright, I'm sitting down, you can tell me, if we get all the carbon in the permafrost into the atmosphere, how warm is our planet, do we know?

NATALI: Not all of the carbon that's in permafrost will be released. Our current expectations is about 10 to 15% of that carbon will be released into the atmosphere. That said, if all of the carbon of permafrost was released, at that point, this is not going to be a habitable planet for humans.

CURWOOD: Sue Natali is a Permafrost Expert with the Woods Hole Research Center and co-author of a paper recently published in “Nature.” Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Sue.

NATALI: Thank you so much for having me.

Related links:

- Woods Hole Research Center press release on permafrost

- About Susan Natali

- About permafrost from NOAA

- Methane and Frozen Ground

- “Climate change and the permafrost carbon feedback” (coauthored by Susan Natali)

- Scientists raise permafrost alarm at UN climate talks

- UNEP Report: “Policy Implications of Warming Permafrost”

CURWOOD: There’s more information about threats related to the thawing permafrost on our website LOE.org, including a link to this paper in the journal “Nature.”

U.S. Methane Emissions Drastically Underestimated

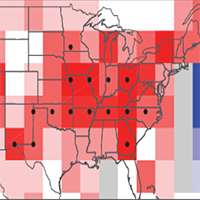

Rising methane emissions across midwestern US (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Jacob)

When the global warming gas methane is first emitted it’s roughly 90 times as powerful as carbon dioxide, and there’s more than twice as much of it in the atmosphere now than there was before the start of the industrial revolution. There are many sources – wetlands, agricuture, landfills, and of course oil and gas production and a massive natural gas leak near Los Angeles drew attention to the environmental impact of methane.

A study from Harvard University published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences documents a spike in global methane emissions to levels far higher than previous federal estimates. The study claims the United States may be to blame for up to 60% of the global growth in human-caused methane emissions. For an explanation we turn to lead author Daniel Jacob, professor of atmospheric chemistry and environmental engineering at Harvard University.

JACOB: So, we tried to look from the satellite data at fingerprints of where methane could be increasing, and we found the large increase over the past decade of emissions of methane in the US, of about 30 percent — which, if you consider what it would contribute to the global increase of methane, would amount to 30 to 60 percent of the global rise in methane.

CURWOOD: You say "fingerprint of methane". What are you talking about?

JACOB: We’re trying to figure out where methane is being emitted, and where the increase in methane is coming from. And so the way you figure this out is by looking at the areas around the Earth where methane is increasing faster than average. And this is what led us to the US.

CURWOOD: So, methane molecules don't have any particular identity. They're all carbon atoms surrounded by four hydrogens. There's not a particular kind of methane that you're able to identify with a fingerprint methane.

JACOB: You're absolutely right. Methane is methane. Now, if you look at methane isotopes you could try to figure out where methane is coming from, but we cannot observe those from satellite.

CURWOOD: Now, some people listening to us would say: ‘But professor, the spike you've identified seems to have started from the time of shale oil and natural gas, the boom beginning in the US. Come on, there's got to be a connection to this.’ How do you respond?

JACOB: I respond that there might be, but our data doesn't provide a smoking gun for figuring out where the methane is coming from. It's just showing that there's been a large increase in methane emissions in the United States. The tempting hypothesis is indeed that it's due to oil and gas, but more work is needed to figure out where that source might be and also what processes are involved. I mean, oil and gas is a very complicated source. You have emissions associated with exploration, with production, with processing, transmission, compression, distribution. And at all these steps in the supply chain you could have emissions, so it's going be difficult to tease out if it is coming from oil and gas, which we really cannot tell.

CURWOOD: Now, how does this compare to other measurements that have been made?

JACOB: We examine a bunch of studies that have been done over the past decade of looking at methane in the atmosphere over the United States, and comparing to emission inventories. And what these studies repeatedly show is that our current national emission inventory for methane that’s produced by the Environmental Protection Agency is too low.

CURWOOD: And of course, one major source of this discrepancy might well be that as things warm, wetlands are releasing more and more methane and the government doesn't go out and ask a wetland how much methane it’s releasing.

JACOB: No, so the government is not looking at emissions from wetlands right now, except manmade wetlands such as rice patties. But we can use satellite observations, again, to see how much methane is coming out of wetlands and the trends associated with that. I think you bring up a good point that the atmosphere doesn't lie. When we see methane in the atmosphere, we know it came out of something. Whereas the emission inventory from EPA doesn't really know about methane in the atmosphere, it just knows about the different activities that are emitting methane. So there really needs to be a partnership between EPA and the atmospheric scientists to resolve the difference that we're presently seeing.

CURWOOD: Tell me, what's the difference between your data and the current federal data?

Daniel Jacob is the Vasco McCoy Family Professor of Atmospheric Chemistry and Environmental Engineering at Harvard University (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Jacob)

JACOB: The EPA gathers information on all of the sources that it thinks are emitting methane, and it's really pretty good at this. So, it knows where all the landfills are, where all the major livestock operations are, the different components of oil and gas supply system, the leakage from coal mines and so on. The inventory that comes out of this is what we call a bottom-up inventory, in that it looks at the individual processes that are emitting methane and tries to estimate how much methane is associated with these different processes with the individual sources. What we can do from the atmosphere side is what we call top-down constraints, in that the atmosphere tells us how much methane there is. And it gives us a rough idea of where it's coming from, but it cannot as easily pinpoint the methane to individual sources.

CURWOOD: And to what extent could satellite monitoring be a way to look at what other countries around the world are doing in terms of methane?

JACOB: I think it's a silver bullet. We've been hampered until now because the satellite observations that we have are fairly sparse. In other words, from satellite we can see globally where methane is coming from, but the picture is a little blurry. But later this year in October, the Dutch are going to be launching a new satellite instrument. And that's going to provide us with a much finer picture of methane emissions, and so we'll be able to observe methane every day around the world with a resolution of about five miles. So this is going to revolutionize our ability to observe methane from space.

CURWOOD: So according to your research we've been underestimating methane emissions for long time. How much might we been underestimating global warming gases from the US in general, do you think?

JACOB: Yeah, this appears to be an issue for the past decade or so that the emissions are being underestimated, and that doesn't come just from us. There are numerous studies that are showing this, so the view is that the methane emissions of the United States are underestimated by 30 to 50 percent. And I would say that's pretty much a consensus view from atmospheric scientists that have been looking at methane emissions from the US.

CURWOOD: Daniel Jacob is a Professor of Atmospheric Chemistry and Environmental Engineering at Harvard University. Professor, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

JACOB: It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Study: A large increase in US methane emissions over the past decade inferred from satellite data and surface observations

- About Daniel Jacob and Harvard’s Atmospheric Chemistry Modeling Group

- Draft U.S. Greenhouse Gas Inventory Report: 1990-2014

- Reconciling divergent estimates of oil and gas methane emissions

[MUSIC: Nina Simone, “See Line Woman,” traditional American /George Bass/Nina Simone, Broadway-Blues-Ballads, Philips]

CURWOOD: Just ahead – Why cleaner air in your office helps you work better - Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joshua Messick, “Cello Suite No 1 in G, Prelude,” Woodland Dance, J.S. Bach, self-published by Joshua Messick]

Turning up the Heat on Frigid Offices

Air-conditioning was invented in 1902 by Willis Carrier. By the 1950s, sales of window air-conditioners were booming, bringing affordable climate control to the home. (Photo: Jason Eppink, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s an encore edition of Living on Earth, and I’m Steve Curwood. Well, the Northern hemisphere summer is winding down, and the days are growing shorter. But throughout these hot months, there’s been a continuing gender divide inside office buildings, with the dog days of summer demanding sweaters and scarves – at least for some folks.

MAN: "My little cubicle is just about right. I wear long pants -- they're wool -- and I have a long-sleeved shirt; I wear a bowtie every day."

SECOND MAN: "I personally feel fine with the air conditioning on, but I do notice that some people in the office get cold very easily. Uh, more women. Definitely more women."

WOMAN: "These offices are like sitting at the bottom of an ice cube tray: they're separated by walls but not all the way up. These are the ice cube trays in terms of how darn cold they are!"

SECOND WOMAN: "I keep a blanket at my desk for when I need it, or a shawl."

THIRD WOMAN: "It's cold. Very cold."

WESA reporter Margaret Krauss bundles up at the Community Broadcast Center in Pittsburgh, August 6, 2015. (Photo: Lou Blouin)

CURWOOD: That’s an unscientific sampling of opinion in Boston – but the same drama is playing out all over – including inside radio station WESA of Pittsburgh, as Lou Blouin of the Allegheny Front reports.

BLOUIN: Forget the tense staff meetings. Forget the latest workplace romance. By far the hottest drama in an office building in the summertime is the war over the thermostat.

PAGE-JACOBS: I wouldn’t call it a war. I would call it a dispute. And I think I would also call it an uneasy peace.

BLOUIN: That’s WESA afternoon host Larkin Page-Jacobs. And in our office here at the radio station, she's one half of an ongoing head-to-head over the temperature in the on-air studio.

PAGE-JACOBS: Josh comes in and turns it all the way to cold for his morning shift…

BLOUIN: She’s talking about Josh Raulerson, WESA’s Morning Edition host.

PAGE-JACOBS: But then when I come to do my shift, it is freezing. I didn’t really know how to address it. You know, sometimes I was a little vindictive, I would push it all the way to hot. And so when he would come in the morning, ou know, he’d feel like he was boiling.

RAULERSON: I’d get in here at 4 in the morning, and I come into that studio and it is stifling…

BLOUIN: That’s Josh Raulerson…

RAULERSON: So I always have to put the thermostat on full cold. And it became quickly apparent to us that we, like, couldn’t agree on where it should be set.

BLOUIN: And that, as you probably know if you work in an office, is not all that uncommon. There are even studies to back that up…

HEDGE: Well, if you look at studies of office workers, and the kinds of things that they complain about, thermal issues are number one.

WESA radio hosts Josh Raulerson and Larkin Page-Jacobs have an ongoing feud over the temperature in the on-air studio. She likes it warmer; he likes it cooler—which is not an uncommon disagreement among men and women in shared work spaces. (Photo: Lou Blouin)

BLOUIN: Cornell’s Alan Hedge has been studying this issue for more than 40 years. In fact, he published the first research on a topic that’s getting a lot of attention today: the differences in thermal comfort between men and women in the workplace.

HEDGE: And what that research showed, of course, was that women were experiencing more issues at the temperatures that were then being set in the environment, which are the temperatures that still tend to be used today.

BLOUIN: In fact, a study just published in the journal "Nature Climate Change" found that the standards of comfort that have endured since the Depression era are likely based on the metabolic rate of a 40-year-old, 155 pound man. And the problem with that, Hedge says, is that women, for a variety of biological and cultural reasons, tend to be colder than men in offices. But Hedge has also found evidence that the average office temp. of 70 degrees in the summer, isn’t really doing anybody much good when it comes to productivity. He says it’s always been assumed that if people are a little bit cool, they’ll do more work.

A hoodie is de rigeur in this woman’s office, despite the outdoor temperature of 85-degrees. (Photo: Naomi Arenberg)

HEDGE: In reality we find the opposite in office workplaces. We find that when people are in an environment that they find to be too cold, typically a temperature like 68 to 70, they do up to a third less work on their computers than if they’re in an environment that is more comfortable.

BLOUIN: That would be something around 76 degrees, which Hedge says, is the temperature where workers are the most productive. Which means, bottom line, we are over air-conditioning our workplaces in the U.S. In fact, geography plays a huge role in what your perception of comfort is. He’s found that people from tropical countries prefer the thermostat in the 80s. And in Japan, they’ve had success cranking the thermostat up to 82, while relaxing the clothing policy at work. Meanwhile, in the U.S. we continue to throw away a ton of money and energy by loading up on weapons to win our own office AC wars.

HEDGE: One of the ironies is that when you look at the sales of personal heaters, the peak months are July and August—which is crazy. It means the company is paying money to over-cool the air. And then you’ve people who are actually trying to warm the environment up.

BLOUIN: Where we’re heading Hedge says is into an era of more and more customization. Right now Cornell is helping to develop a technology that sort of does the inverse of what we do now. It would leave temperatures a little higher in the office overall, and then provide high-tech cooling at the desk-level for people who get too warm. He says it could be on the market by 2019. But we don't need to wait that long to turn up our thermostats, let people wear shorts to work, give workers desk fans, and in doing so, make everyone around the office a little bit more comfortable. I’m Lou Blouin.

A woman keeps a shawl along with a jacket at her desk, anticipating the effects of air-conditioning. (Photo: Naomi Arenberg)

CURWOOD: Lou Blouin reports for the Allegheny Front. Well, since these arctic offices seem so ubiquitous, and the complaints are such an old story, why is it still going on? That’s a question for Jennifer Amman, the Buildings Program Director for the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. I asked her if this all isn’t kinda nuts.

AMANN: It is crazy, and I have heard it all before. This is a long-standing issue with many causes and in fact we suffer from it ourselves. Even at ACEEE, we have folks walking around in fleeces in mid-summer to stay warm in our office, and I know from our personal experience even in our own office space it can be a real issue for morale. It's very hard to keep employees happy when they're uncomfortable physically in their environment.

CURWOOD: So people are uncomfortable, unhappy, too cold, and it must cost a fortune to keep it too cold.

AMANN: That's right. Cooling is one of the largest energy users in commercial buildings, particularly offices, and so this is a real opportunity to change that, and I think we're seeing a number of changes in the types of technologies that are available, the increasing number of controls and sensors, new types of systems that are better able to operate at different loads, and even new systems that can allow users to have some input and even individual control over heating and cooling of their own spaces.

CURWOOD: Imagine that. Somebody sitting at a desk able to control the temperature where he or she is sitting? I mean, I don't think I have ever been in a large office where that's even possible.

For every degree the thermostat is increased during the summer, offices gain energy savings of two to three percent. This means that a difference of 72 to 77°F can save as much as 15%. (Photo: AJ Batac, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

AMANN: Right. Well, as buildings are increasingly retrofit and with new construction it becomes more possible to do these things but it might take awhile to get the technology changed out and get the new systems installed, but in the meantime there are lots of other things that can be done. Just installing more thermostats and working harder to make sure that the conditions throughout the space actually reflect the temperature settings on the thermostat, making sure sensors are in the right place, you know at the level where people are sitting. And then there are a number of interesting apps coming online that allow users and occupants within the space to record their comfort at various times of the day. There are activities that can be done to come in and more regularly check out the systems within buildings and now we're able to do that much more in an automated fashion. These things can all restore the system, find out where the deficiencies are, correct them without requiring an upgrade to the whole heating and cooling system.

CURWOOD: Jennifer, what are some of the behavioral changes that can help save energy in the summertime?

AMANN: So, one of the biggest changes would be to have everyone dress for the season, and that would allow building operators to set the temperature at a more appropriate level. Over time I think this has become more of an issue because a lot of the ideas about how cool it should be an office space came when the air-conditioning was new, you know it was very much a sign of prestige and luxury to have a cool space and you had men wearing suits all summer and you had even women wearing stockings and you know much more layers of insulation. But now we find folks are wearing much more casual clothing.

CURWOOD: The typical office today seems to be set for 70 degrees, maybe 72. What if we set it to 77 given the concerns we have about energy use in relationship to climate change and overall efficiency?

Jennifer Amann is the Buildings Program Director at ACEEE. (Photo: courtesy of ACEEE)

AMANN: The general rule of thumb is that you could save 2 to 3 percent for each degree that you raise the temperature. So going from 70 to 75, or 72 to 77, you would looking at 10 to 15 percent energy savings just from that one simple measure, and just because we have women complaining because they are freezing and men saying “I'm OK, I'm comfortable at the lower temperature”, doesn't mean that the men wouldn't also be more comfortable at a higher set point. So really being able to move forward to that type of an interior temperature could reduce environmental impact, cut energy bills substantially, and help us all be a little bit more comfortable and more productive and happier in our workspaces.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Amann is the Buildings Program Director for the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy in Washington. Thank you so much, Jennifer.

AMANN: Thanks, Steve. My pleasure.

Related links:

- Allegheny Front’s “Why Frigid Offices are Bad for Everybody”

- When it comes to studies of office complaints, thermal issues poll highest.

- A study found why offices are set to colder temperatures and why women aren’t metabolically equipped to handle it.

- Differences in thermal office comfort exist between countries. Some can take the heat.

- “Chilly at Work? Office Formula Was Devised for Men”

- About retrocommissioning to improve energy efficiency

- Temperature standards developed by ASHRAE

- About the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy

- About Jennifer Amann

[MUSIC: Kevin Tolly, “Baby It’s Cold Outside,” Frank Loesser, Youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P4QuBgwJi2Q]

CURWOOD: You can hear our program anytime on our website, or get an audio download.

The address is LOE dot org. There you’ll also find pictures and more information about our stories. And we’d like to hear from you:You can reach us at comments @ l-o-e dot org. Once again, comments @ l-o-e dot O-R-G.Our postal address is PO Box 990007, Boston, Massachusetts, 02199. And you can call our listener line, at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-99-88.

[MUSIC: Kevin Tolly, “Baby It’s Cold Outside,” Frank Loesser, Youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P4QuBgwJi2Q]

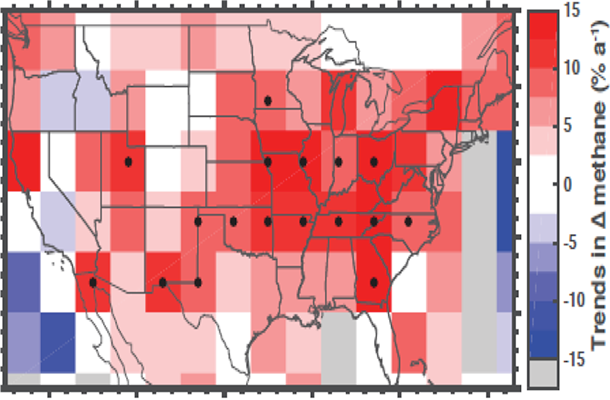

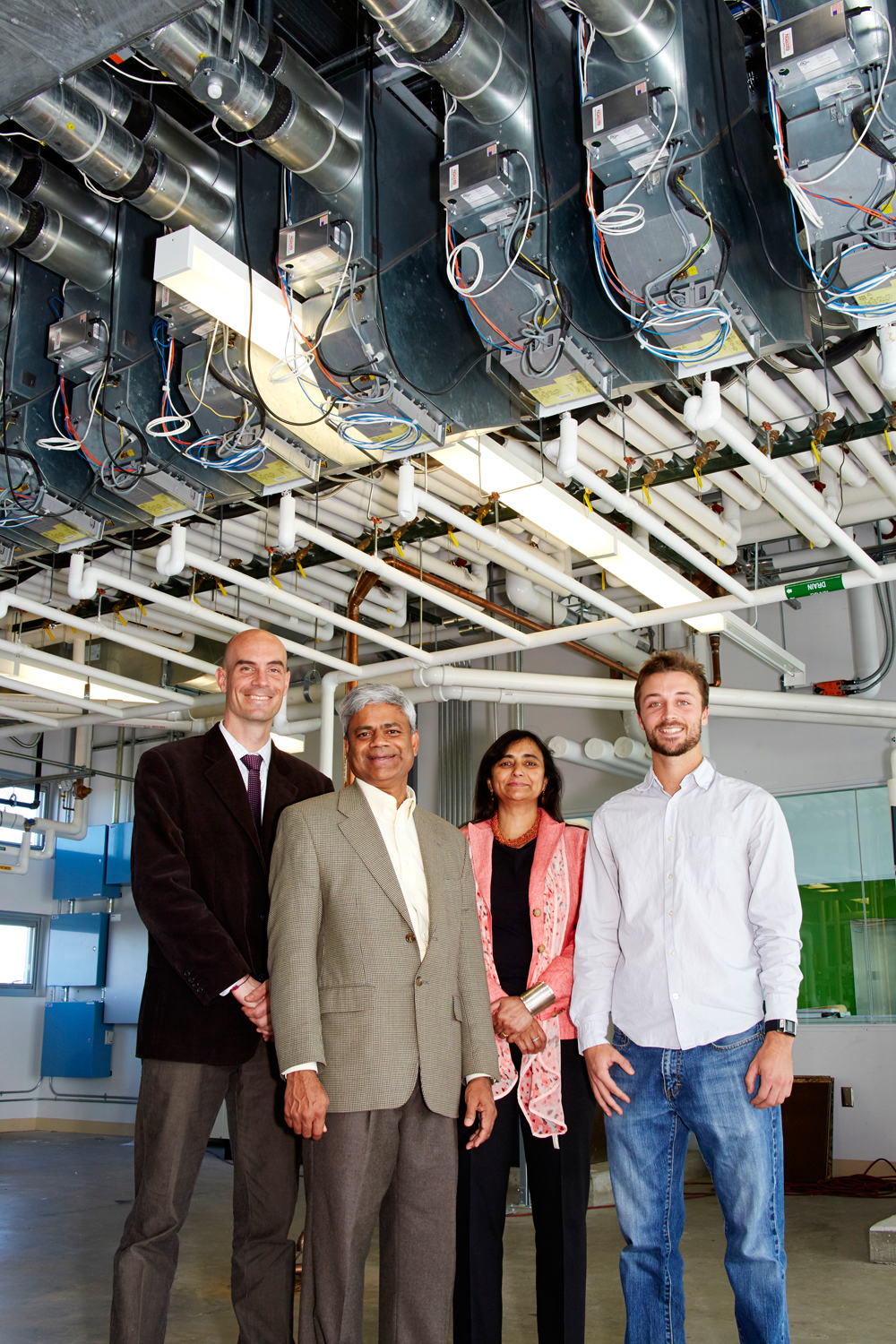

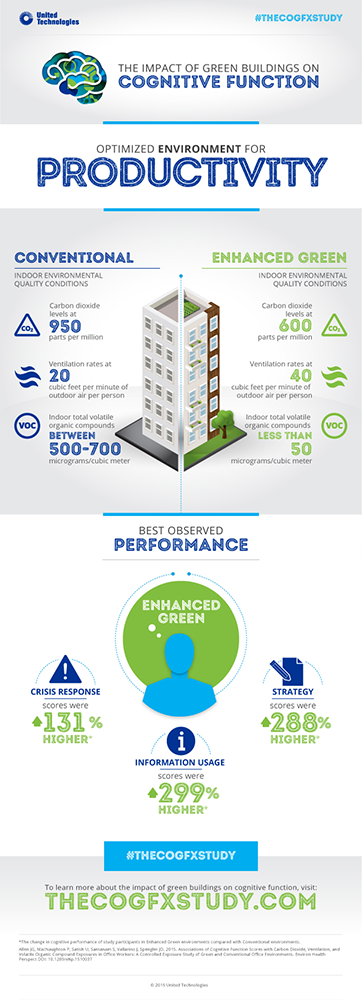

Better Office Air Makes For Better Thinking

Twenty-four professionals participated in the six-day COGfx Study. Each conducted their normal work activities within a laboratory-setting that simulated conditions found in conventional and green buildings, as well as green buildings with enhanced ventilation. (Photo: United Technologies)

CURWOOD: Think air quality and you’re likely to consider outdoor air, full of diesel fumes and smoke and dust. But most of us spend 90 percent of our time inside. Now ground-breaking research by a team from Harvard, Syracuse University and SUNY Upstate finds that dramatically improving indoor air quality can more than double the reasoning scores of workers. Chemicals found in paints, furniture and flooring -- so-called volatile organic compounds, or VOC’s, are the main problems. And common office concentrations of carbon dioxide also modestly reduce cognitive functioning. The lead author of the study, published in Environmental Health Perspectives is Joe Allen of Harvard’s Center for Global Health and the Environment. Welcome to Living on Earth, Professor Allen!

ALLEN: It's a pleasure to be here. Thanks.

CURWOOD: Your study looks at the impact of indoor air quality on cognitive functioning, so tell me about the study. How did you do this?

ALLEN: We set up in the Syracuse Center of Excellence. They have a simulated office environment, and we enrolled what we called knowledge workers, people who work in office environments. We enrolled them to come to the Syracuse Center of Excellence and do their normal work routine in this office. From the floor below, we were able to manipulate the indoor environmental conditions in their workspace unbeknownst to them. At the end of each day, we administered a cognitive performance test, and the analysts are also blinded to the conditions that were testing that day, so that way it's a double-blinded study, it's a controlled environment, and we were able to manipulate one variable at a time to tease out the effect of that variable on the cognitive performance scores of people in that space.

CURWOOD: Now, how did you measure the cognitive impacts?

ALLEN: So we measured cognitive performance with a great tool called the simulated management strategy tool, and it's a neat tool because it tests real world decision-making performance. I think it's best if I give you an example. So, in one of the scenarios, the participants are asked to play a game, and they are essentially the mayor of a city, and in that role they are prompted with things that happen throughout the day and they have to respond to these prompts throughout the day, and they have a wide axis to a wide range of information, and we watch how they plan, strategize and what decisions they ultimately make in response to the information coming at them.

The research team responsible for the study (From left) Principal Investigator Joseph G. Allen, DSc, MPH, Assistant Professor of Exposure Assessment Science, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; Co-investigator Suresh Santanam, ScD, PE and Associate Professor of Biomedical and Chemical Engineering, Syracuse University; Co-investigator Usha Satish, PhD, Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, SUNY Upstate Medical University; and Project Manager Piers MacNaughton, MS, doctoral candidate, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (Photo: United Technologies)

It's really similar to how we all operate every day. You're sitting at your desk, you have access to unlimited information with the Internet, your phone rings, you have text messages coming in, you're answering e-mails, the boss comes in, a crisis happens, and we want to simulate this with this tool to test how people respond under this real-world scenario of dealing with information, figuring out how to use information, are they optimized, how they do in a crisis and importantly, how do you recover after a crisis, are you done for the day or do you go back to your nice strategic planning in taking actions based on the prompts that are coming in.

CURWOOD: So what did you find? How did people perform these cognitive tests based on their exposure to changes in air quality?

ALLEN: Yeah, we found some quite striking results. We found a doubling of cognitive performance scores for people who spent time in the optimized green building environment compared to those same people when they were in the conventional office building, an indoor environment designed to simulate the conventional office building. And three domains, three cognitive functioning domains in particular had the strongest scores. These were crisis response, strategy, and information usage. And these three cognitive function domains are most closely tied to productivity.

CURWOOD: Those numbers are huge. That's a big disparity. How surprised were you by those findings?

ALLEN: To be quite honest, we were shocked. We think this is a big deal, that the findings are strong, the magnitude of the effect is quite large and the really nice thing about the studies is that we weren't testing anything exotic. We didn't introduce chemicals into the environment that you don't typically encounter. We didn't introduce ventilation rates that are impossible to obtain. The idea was to simulate office environments that can easily be obtained. So these are chemicals that we are commonly exposed to, these are outdoor ventilation rates we can obtain in most buildings. So this is what's shocking is that you see this big effect - the magnitude is big, and the effort it takes to reach that wasn't that much.

CURWOOD: Joe, how does all this indoor air pollution affect us physiologically? How do you get from the chemical to cognitive impairment?

ALLEN: Well, this is a great question and it's currently unknown, so there's no answer right now, but we hope and we know - there are people working on this and we're starting to work on it too - is the next question is why is this happening, or how is it happening...so physiologically, mechanistically what's happening that's causing this decrement or in some cases improvement in cognitive performance functioning. So we think that the next six to 12 months we'll start seeing a lot of researchers attacking that question.

CURWOOD: So let's be specific about these chemicals. What's the impact of the Volatile Organic Compounds, the VOCs?

The study was designed to determine the independent and combined effect of volatile organic compounds, ventilation and CO2 on workers’ cognitive function. These factors were controlled by a machine room located directly below the workspace. (Photo: United Technologies)

ALLEN: So VOCs...I mean, we're exposed to VOCs every day in just about every environment we're in, and we know they cause things like eye irritation or upper respiratory irritation, some of them are carcinogens, so we know these compounds can be irritants, and now we're learning that they can also impact cognitive function.

CURWOOD: Now, what about carbon dioxide?

ALLEN: Yeah this is very interesting. So, the second part of our study we looked at the impact of carbon dioxide on cognitive function, independent of ventilation - outdoor carbon dioxide concentrations are typically around 400 parts per million right now. Indoors, we routinely see carbon dioxide between 800 and 1,200 parts per million, but it's not uncommon to see carbon dioxide as high as 1,500 parts per million or even up to 3,000 parts per million. So we found in our study is that when people were in an environment with low-carbon dioxide concentrations and they were moved to a level of about 950 parts per million, a level we find in most indoor spaces, we see a 15 percent decrease in cognitive performance scores for the people in that space, and when they move to an environment with 1,400 parts per million, we saw 50 percent lower cognitive performance scores when they were in that environment.

CURWOOD: So, a huge impact.

ALLEN: Yeah, very big. I mean this is new for our field. Carbon dioxide, we measure it all the time when we're doing studies of buildings and health because it's a good indicator of how well the space is ventilated. But now we’re starting to see that maybe carbon dioxide isn't just this useful tool as a proxy for ventilation and other things that are building up in our environment. It might actually be a direct pollutant, a primary pollutant.

Infographic of the results (Photo: United Technologies)

CURWOOD: So you say that there's this decrease in cognitive functioning when you have poor air quality or even conventional office air quality compared to greener air quality. How do you translate that into dollars and cents, let's say, for a company looking at its workers?

ALLEN: Yeah, I'll tell you about our next paper that we publish that should be out in the next month or two because we thought this was a really important question to ask is how can we take the data we have now on cognitive performance and turn it into dollars because we know that research informs practice, and what a lot of these practitioners want to hear is how is it going to impact my bottom line. So we looked at the energy penalty, or the energy cost for increasing outer air ventilation to the levels we did in the study where we found a benefit to cognitive performance and we find that it's on the order of $30 per person per year to double your outdoor air ventilation rate. Then we used the same information from our study and looked at the cognitive performance improvements normalized to what we find in the general population and we estimate that the benefits to productivity are on the order of $6,000 per person per year.

CURWOOD: So what do you hope comes out of this study?

ALLEN: We designed this study specifically to look at what building factors could be improved that would lead to benefits to cognitive performance of people in that space, and there's a positive story here is that there are things we can do right now in most spaces that will reduce the chemical concentration that we're exposed to and increase the amount of air coming in, and we think this will lead to better cognitive performance based on the results of the study.

CURWOOD: You know, when you do a home energy audit, they come and they do this pressure test to see how much leakage you have, and the less leakage you have the more efficient the home is. To what extent is this a zero sum game if you improve indoor air quality, you have less energy efficiency?

ALLEN: Yeah, Steve, I think it's a false choice we've been given over the past 30 years where there has been a trade-off traditionally between energy efficiency and human health, and that can't be the way we move forward. And we know that you can make decisions now in how buildings are designed and how your ventilation system is performing and the choices in the products you make can be used to optimize indoor environmental quality while optimizing energy performance and cost.

CURWOOD: Joe Allen is an Assistant Professor of Exposure Assessment Science at the Harvard T.H. Chan school of Public Health. Thank you so much.

ALLEN: My pleasure. Thank you.

Related links:

- Study: The Impact of Green Buildings on Cognitive Function

- More about the study and its implications from United Technologies

[MUSIC: John Williams/Paul Clarvis,/Richard Harvey/Chris Laurence, “Mitopa,” The Magic Box, Paul-Bert Rahasimanana, Sony Classical]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Tasting America’s most unusual native fruit -- That’s just ahead on Living on Earth, stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Beppe Gambetta and Filippo Gambetta, “Ninna Nonna,” Rendez-vous, Gadfly Records]

Pawpaw: America's Forgotten Fruit

Pawpaws grow in clusters of one to six green fruit, which darken to a yellowish-black as they ripen. (Photo: Anna Hesser, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's an encore edition of Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. The largest edible fruit native to the United States was once a treat and a source of sustenance for Native Americans, presidents, and enslaved African Americans. Today it can still be freely foraged in the forests of twenty-six states. Chances are though, you’ve never tasted and only ever sung about the pawpaw. Andrew Moore explores the economic, biological and cultural reasons for our naiveté about this singular fruit in his book, Pawpaw: In Search of America’s Forgotten Fruit. He joins us now. Andrew, welcome to Living on Earth!

MOORE: Steve, thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: You've brought in your book, "Pawpaw: In Search of America’s Forgotten Fruit" and you've brought in a pawpaw.

MOORE: Yes, a pawpaw itself, and this is maybe one of the last pawpaws that I'll be lucky enough to get this year.

CURWOOD: Describe it for us would you please.

The taste of the pawpaw is usually described as a cross between a banana and a mango, but Moore says that subtler flavors like vanilla, caramel, and melon can also be discerned in the fruit, and its flesh varies in color from pale yellow to orange. (Photo: Mr.TinDC, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MOORE: It kind of looks to me like a small mango. It's very green. Some other people describe it, it kind of looks like a russet potato.

CURWOOD: It is really fragrant.

MOORE: Really fragrant. The studio is really filled with the aroma now.

CURWOOD: I describe it as almost a mango aroma as well, so I've got to ask what it tastes like?

MOORE: Sure, so you mentioned mango already and a lot of people do describe it commonly it as a cross between a banana and a mango and what that's really getting at is that it has an unusual tropical flavor for an otherwise temperate fruit, and then the banana aspect gets at this creamy texture that the pawpaw has.

CURWOOD: Well, can I find out?

MOORE: Sure, yeah, do you want to cut into it?

CURWOOD: Yeah, OK, you go ahead. You're the expert cutter here.

[SOUNDS OF KNIFE ON PLATE AND CUTTING]

MOORE: The way I like to do it is to cut it in half, kind of like you might an avocado and twist it apart like a double stuffed Oreo and then when you do that you reveal essentially two cups of custard. The pulp as you can see is is this vibrant yellow, near orange in some places, and then you've also revealed a few rows of seeds down the center of the pawpaw and these are large black lima bean sized seeds that you can pick around or pull apart.

The Ohio Pawpaw Festival, which always takes place at the height of Ohio’s pawpaw season in September, drew a crowd of over 10,000 this year. (Photo: Andrew Moore)

CURWOOD: Now, I think it's been 20 or 30 years since I’ve tasted a pawpaw, so here it goes. Yum, that's really good.

MOORE: Does it taste like you remember?

CURWOOD: Yeah it tastes like it's got this slight little tangy edge to the banana, but it's mango, but no wait it's banana, no, wait it's mango and it's delicious. You know there are a lot of things one can do in life, Andy, why have you spent so much time researching, traveling around, paying attention to pawpaw? What drew you to the pawpaw?

MOORE: When I learned about it, first of all what happened was I was captivated. I was at the Ohio pawpaw festival and out in the woods, outside of the festival fairgrounds is a patch of wild pawpaws, and the experience of picking pawpaws from the trees, of picking them up from the ground, this wild bounty, this tropical tasting fruit that I had never heard of, that none of my family or most of my friends have never really heard of this thing, I was fascinated that something this good, this large, it's the largest edible fruit in the Native American woods, that it could be so unknown. And so I just wanted to learn more, so I just kept researching and looking online and I met the people who are working with pawpaws and I was certain that I wanted to write a story because I realize it had a really compelling human story as well.

CURWOOD: So you started on a pawpaw quest. What's it like to go pawpaw hunting?

MOORE: It's a lot of fun, and that was another reason why I set out writing the book. It was just --it was really fun to go to these places, whether it was wild patches on the banks of the Mississippi or whether it was Monticello in Mount Vernon or an experimental orchard where people were growing pawpaws and doing selective breeding. It was just a lot of fun to go to these places and meet these people.

CURWOOD: By the way, describe the pawpaw tree for me. What's it look like?

MOORE: Sure. Yeah, the pawpaw tree, and again it's confusing to me as to why it would be so unknown because the tree is beautiful as well. It has this lovely pyramidal shape when grown in full sun and it has these long tropical looking leaves. There are among the broadest and longest leaves you'll find in eastern forests and in fall they turn a striking yellow.

CURWOOD: And where can you find pawpaws?

MOORE: I often say that the pawpaw is a river fruit. It's native to 26 states in the eastern US and many of these rivers in these states are, in fact, lined with pawpaws in the deep alluvial rich soil and so that's a good place to start looking for them.

CURWOOD: So how come most of us have never heard of the pawpaw?

Pawpaw gelato is one of the more popular creations made from the fruit. (Photo: Andrew Moore)

MOORE: Right, well, I call it the forgotten fruit - that's in the subtitle - certainly some people have maintained memories of pawpaws, but for the most part we stopped knowing pawpaws when we stopped going to the woods for food. In the middle of the last century with the rise of supermarkets and global food and industrialized foods, our diets became a lot more homogenized and industrial and something that you would have to go to the woods to gather was left by the wayside. And pawpaw is not the only food certainly that we stopped eating and that we had neglected. There were so many heirloom fruits and vegetables - we had thousands of apples and old tomatoes. And so pawpaw is among those fruits that were lost, but that thankfully we're seeing a revival of.

CURWOOD: So, since it's free and available on the wild and such, what's your favorite survival story of somebody who needed the pawpaw to get over whatever challenge they were meeting?

MOORE: Well, among the early stories are Lewis and Clark subsisting on pawpaws at the end of their expedition along the Missouri River. They had completely run out of food and all they had was the wild bounty of pawpaws. Some people when they talk about it they'll say that the pawpaw saved them from hunger or they were near starvation, but in reality there were just so many pawpaws it was never a concern. They were all content and happy and just eating pawpaws for three days.

Marc Boone harvests pawpaws on his property in Michigan, at the northernmost extent of the pawpaw’s range. (Photo: Andrew Moore)

CURWOOD: So, historically, how did Native Americans use the pawpaw?

MOORE: Unfortunately there's not a lot of citations for Native American foodways before Europeans. There are some citations that survive that that we pawpaw people are thankful for. The Iroquois, for one, are cited as having dried pawpaws and cooked them into corncakes, which I found fascinating because corn is low in niacin and pawpaw is high in this nutrient. It's high in antioxidants and some of the same antioxidants that are found in red wine and chocolate. We also know that is high in various vitamins, vitamins A, C, potassium. These old folkways, they develop for a reason and there's a lot of wisdom in them.

CURWOOD: What's the relationship between the pawpaw and people of color?

MOORE: Enslaved African-Americans, they were looking to supplement diets if they had the liberty to pick things from the wild, pawpaw would've been one of those things that they could've gathered each year, as well on the Underground Railroad. Slaves seeking freedom in the north, pawpaw would have kept people alive as they were going north.

A pawpaw grown by Jerry Lehman weighs in at a whopping pound-and-a-half. (Photo: Andrew Moore)

CURWOOD: So, as you went on your odyssey around America looking for pawpaw, how many festivals did you get to?

MOORE: There were two prominent festivals that I went to when I was researching: the Ohio which is a large gathering now in its 17th year, around 8,000 people come out every year for that, and then in North Carolina which was newer at the time which is also growing. But now there's festivals in Rhode Island and Maryland, in New York, Pennsylvania...they're just popping up everywhere and so it's a really fun time for pawpaw people.

CURWOOD: And how do people who hunted and ate pawpaws a long time ago, say as kids, how do they react now when they taste their first pawpaw in decades?

MOORE: It's a really fun thing to share pawpaws with people who haven't had them in decades. They remember and they say, “oh, I used to love eating these as kids. We'd go on the river and pick them.” Or if they were coming home from school this was candy for them, they didn't have access to all these sweet foods like we do today, it was such a cherished treat, and it really seems like a personal fruit, everyone has these personal memories of gathering pawpaws, and that I think some of that has to do with the fact that as children, they did wander and gather these, but they were also shown this by loved ones, grandparents, or parents. It was like a family tradition to go and gather these things.

CURWOOD: The pawpaw place?

MOORE: Yes, the pawpaw place. The picking place.

CURWOOD: What are the various ways that people eat and I guess can even drink pawpaws these days, huh?

MOORE: Yeah, these days the skies the limit with what you can do with pawpaw and it's an interesting time. There's some great recipes out there but I think the best things that you can do with the pawpaw are products yet to be seen as people start experimenting with it. I make a pretty good pawpaw ice cream, pawpaw gelatos, sorbets, these are all very wonderful. Crème brûlée even and recently at the Ohio Festival, I tasted pawpawcello, so like a limoncello, a hard pawpaw lemonade and there were 11 pawpaw beers on hand. I didn't get a chance to drink all of them.

CURWOOD: That's right, I mean, good sweet fruit can lead to booze.

MOORE: Booze, absolutely and that's a tradition that goes as far back as the 17, 1800s. People in and around Pittsburgh and in the Ohio Valley down through Ohio were making pawpaw brandy and liquor and beer, and it's been known to be a strong alcohol even from those days on through today.

CURWOOD: Pawpaw kapow.

MOORE: [LAUGHS] Yeah, that's right.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] What are some of the challenges of cultivating and marketing pawpaws?

MOORE: Often it's said that the pawpaw's short shelf life and its fragility is why it has not been cultivated. That's a good starting place for talking about problems in domesticating the pawpaw. It is soft, and it does have a short shelf life, so it's not necessarily a fruit that lends itself well to sitting on the back of a truck and then going to distribution centers and then sitting on a supermarket shelf for several weeks. So it's just going to have a different niche. It's maybe not going to be something that is found in every Wal-Mart across the country, but it's more likely something that will be found at farmer's markets and local food co-ops.

CURWOOD: And perhaps on a menu of perhaps a local restaurant.

MOORE: Absolutely. We're seeing that more and more from New York to Missouri, chefs are adding it into their menus and doing wonderful things to it.

Author Andrew Moore found numerous pawpaw trees in easternmost Kentucky. (Photo: Andrew Moore)

CURWOOD: Now, at one point in your book you write about Neil Peterson working to improve pawpaw traits. Tell me his story.

MOORE: Sure, he's often described as a Johnny Pawpawseed kind of character. He was a graduate student at WVU and he tasted his first pawpaw along the banks of the Monongahela, and like myself and so many others, he was excited and eager to learn more, and as a plant scientist and a horticulturalist, Neal had the skills to try to do something with it, and so he set about doing a breeding experiment, and he started crossing the country himself seeking out old plantings and old cultivars from 50, 60 years ago when people had a greater interest in pawpaw and had started selecting pawpaws and naming them. So he planted two orchards with well over a thousand trees and after several decades selected the best pawpaws and released them to the public. Neal named his pawpaws after American rivers with Indian names in tribute to the original horticulturalists of the fruit - so Susquehanna, Shenandoah, Potomac - those are Neal's pawpaws and they're considered by many to be among the best that are available.

CURWOOD: Andy, could you please read from your book?

MOORE: I'd be happy to.

CURWOOD: Just describe for me with what's going on here when the search for the Ketter fruit.

MOORE: Yeah, in Ironton, Ohio I had been looking for the lost Ketter fruit. It was the prize-winning fruit from the 1916 contest for the best pawpaws in America, and I spent about three days searching for it.

[READING] In the morning, after a biscuit and fried apple breakfast, I decided to look for the trees planted by the uncle of my waitress at Jim's. Since the Ketter fruit has thus far eluded me it would be a boost in my sleuthing esteem to at least track down something. I find them, a massive pair, each 30 or 40 feet tall reaching above the power lines, and more or less right where she said they would be. Their leaves are deep green fading to yellow at the top of each pyramidal shape they've managed to make a Bradford pear or a black walnut look small in comparison. I stand in the grass taking photos when a neighbor calls out to me from her porch across the road. "Some people want to cut those trees down," she says. I ask why and who. "Just some neighbors on the block," she says. "They just want them gone. Don't want them anymore." I told her I don't see any sense in that. That they're good trees. "Tell me about it," she says. "I'm confused by all of it." But at least it offers some explanation as to why some things disappear - whims of the obstinate.

Andrew Moore is a writer and gardener who lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. (Photo: courtesy of Andrew Moore)

CURWOOD: How many of these do have in your backyard now?

MOORE: I have three trees in my backyard. It is a small backyard otherwise I might have more.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] And are they big enough to produce fruit yet?

MOORE: I'm hoping to get my first fruit next year actually. The flower buds have formed and I'll see them next spring and hopefully we get some fruit.

CURWOOD: So where oh where is little Andy?

MOORE: Way down yonder.

CURWOOD: In his pawpaw patch, huh? Andrew Moore is a writer and gardener living in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, just within the range of the pawpaw. "Pawpaw" is his first book. Andy, thanks so much for taking the time.

MOORE: Steve, thanks so much for talking to me.

Related links:

- Pawpaw: In Search of America’s Forgotten Fruit

- About the pawpaw fruit

- The Ohio Pawpaw Festival

- The Kentucky State University Pawpaw Program

- Facts about pawpaws

[MUSIC: The Even Dozen Jug Band, “Mandolin King Rag,” The Even Dozen Jug Band, Larry Hensley, Elektra]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week with sounds of the Earth…

[SOUNDS OF BURPS AND WARBLES]

CURWOOD: These are Earth sounds as you’ve probably never heard them – sped up 10,000 times and transposed up about 13 octaves…

[STRANGE REVERBERANT SOUNDS CONTINUE]

CURWOOD: The sounds come from seismic recording stations in North America and Central Asia

[CHIRPS AND BURPS CONTINUE]

CURWOOD: The frog-like burbs you can hear are earthquakes, large ones followed by the chirps of aftershocks.

[MORE STRANGE SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: John Bullitt created this unusual soundscape of our solid, restless planet for the CD Earth Sound.

[MUSIC: Joshua Messick, “Ancient Roots,” Woodland Dance, self-published by Joshua Messick]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Anica Green, Jay Feinstein, Emmett Fitzgerald, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Charlotte Rutty, Adelaide Chen, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. Jake Rego engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe, Tom Tiger and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at l-o-e dot org - and like us, please, on our facebook page - it’s PRI’s living on earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes fom the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth