September 2, 2016

Air Date: September 2, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Climate Disruption Fuels Stronger Storms

View the page for this story

Climate change is already loading the atmosphere with more moisture, increasing the severity of hurricanes and other storms. With simultaneous tropical depressions in the Gulf and the Atlantic, and two hurricanes near Hawaii, meteorologist Jeff Masters tells host Steve Curwood that the familiar weather patterns are gone, and the U.S. may face more extremes in the coming decades. (08:30)

Gulf Oil Leases Spark Outcry But Little Revenue

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

Following unprecedented flooding in Louisiana, citizen activists tried to stop the government’s recent auction of 4,400 oil and gas leases in the Gulf of Mexico, but the auction went ahead despite protests. However, the low price of oil meant that just a fraction of the parcels up for auction were sold. Anne Rolfes of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade tells Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer why some people living along the Gulf are wary of new drilling in its waters. (05:00)

Linking Fracking and Radon

/ Julie GrantView the page for this story

Pennsylvania homes have high levels of radon, a substantial risk factor for lung cancer. A recent research project from Johns Hopkins University surprised state experts when it found a correlation between the natural gas fracking boom and an increase in radon levels. But as the Allegheny Front’s Julie Grant reports, that may not be the whole story. (07:10)

Science Note: A Parasite Setback

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

The Guinea worm, an unpleasant parasite that once infected millions of people in Africa, was nearly eradicated. But the worm, which grows up to three feet long inside the body, and causes pain and suffering as it emerges through its host’s skin, is hanging on by infecting dogs, as Living on Earth’s Don Lyman reports in this note on emerging science. (02:15)

Beyond The Headlines

View the page for this story

In this week's round-up, Peter Dykstra speaks with host Steve Curwood about new research into drug-resistant fungus, and the threat to one of America’s favorite fruits. Also, he presents a roundup of changes warmer ocean waters are bringing to sea creatures off the Atlantic coast, and remembers the failure of a big solar leader and a win for blue whales. (04:25)

BirdNote: The Zone-tailed Hawk

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Turkey vultures soar over the landscape, searching for dead animals. But the Zone-Tailed Hawk, an American raptor that’s a vulture look-alike, soars with them, its sharp eyes searching for mice and birds that ignore the carrion-seeking birds. Michael Stein has today’s BirdNote. (01:50)

Your Brain On Parasites

View the page for this story

Parasites have been on Earth for millions of years, and exist in every type of animal and ecosystem. Writer Kathleen McAuliffe’s recent book, “This Is Your Brain On Parasites”, describes some of the many ways these creatures manipulate their hosts’ behavior to ensure their survival and succesful reproduction. As she explains in conversation with host Steve Curwood, some may even affect human behavior and increase the chance of mental illness and car accidents. ()

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jeff Masters, Anne Rolfes, Kathleen McAuliffe

REPORTERS: Julie Grant, Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman, Michael Stein

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Record breaking floods, mounting drought and wildfire, four active tropical depressions. For a leading weatherman, things no longer seem normal.

MASTERS: I don't recognize the climate anymore. I mean I look at the weather maps in the morning sometimes afraid of what I'm going to see. It's just gotten so insane. The climate of the 20th century is gone.We're in an entirely new climate regime, and it is extremely intense.

CURWOOD: Also, levels of radon are rising in Pennsylvania, and some scientists think the rise in fracking could be responsible.

CASEY: We saw at the same time that fracking was going on, increased levels of indoor radon in the places that had the most fracking. And we found that buildings that were closer to more drilled wells had significantly higher indoor radon concentrations than buildings located farther away.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada, “Zoetrope,” A Beautiful Place Out In The Country (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies. innovating to make the world a better more sustainable place to live.

Climate Disruption Fuels Stronger Storms

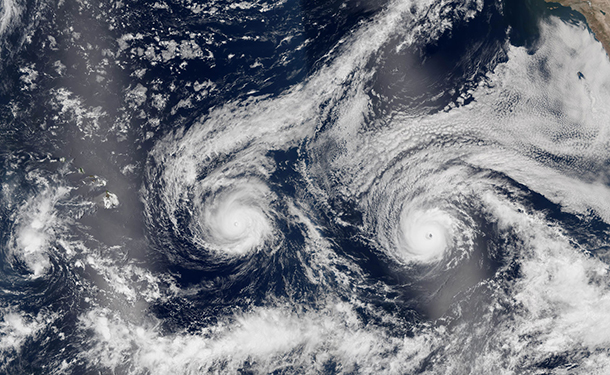

NASA Earth Observatory image of hurricanes Lester and Madeline taken August 29, 2016, when both storms were hovering between Category 3 and 4. (Photo: Jesse Allen / NASA Earth Observatory, using VIIRS data from the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership, CC government work)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. All of a sudden it seems here in North America we are getting a series of unnamed storms seemingly without warning which dumped historic amounts of rain and washed out whole communities. Louisiana is still recovering from the record flooding that displaced thousands from their homes, and as we record this broadcast, Florida, the southeast, and even Hawaii are getting deluged. But even as some regions are getting drenched, others are going dry, leading to yet another intense wildfire season that is incinerated forests from Alaska to Southern California. All this chaotic weather is no mystery for Jeff Masters, the Director of Meteorology for Weather Underground. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Jeff.

MASTERS: Hey, thanks, Steve.

CURWOOD: So what I'm noticing recently are all these massive yet unnamed storms like the one that was just so devastating around Baton Rouge, Louisiana. What's going on?

MASTERS: Yeah, the Gulf of Mexico water temperatures are near record levels this summer. We've had water temperatures near 90 degrees Fahrenheit, and when you get that kind of supercharged water in the Gulf of Mexico it makes for supercharged storms. You get a lot of evaporation off the ocean, that means there's a lot of water vapor in the atmosphere that makes for intense downpours.

CURWOOD: So what's leading to all this hot water in the Gulf of Mexico do you think?

MASTERS: The Earth just experienced its warmest year on record. Actually it's been two consecutive warmest years on record and we're going on three. And so you got a background state that's very warm and then on top of that there are some national weather patterns that have resulted in light winds of the Gulf of Mexico so less stirring up of the waters than usual and that allows for them to heat up.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about how the hurricane season is looking for Gulf of Mexico as well as the Atlantic coast. How intense of a hurricane season do you expect in this region this year?

Tropical Storm Hermine, as pictured on August 31st by NOAA's GOES-East satellite on Aug. 31 at 3:30 p.m. EDT. (Photo: NASA/NOAA GOES Project, CC government work)

MASTERS: It should be the most intense hurricane season since 2012, the year of Hurricane Sandy, but that's not saying a whole lot since the last three years have been exceptionally quiet, although there have been some storms out there they've been guided by steering patterns in the atmospheric winds that have been shutting them away from the coast. This year looks a little different. We're seeing the steering patterns shift so that the US is more in play now, and we're seeing a lot less in the way of unfavorable sorts of upper level winds that tear these storms apart before they even get started. We expect an above average season, not greatly above-average like 2005, but still it's going to seem like a lot since we haven't seen for many storms last three, four years.

CURWOOD: So, we're talking on the Tuesday, the 30th of August. What do you think will happen with the tropical depression that's currently in the Gulf of Mexico?

MASTERS: But the time you're airing this it could be very well sitting off the coast of the mid-Atlantic or New England generating some high surf along the beaches all the way along North Carolina to Massachusetts. The other possibility is to just go out to sea. I don't think it's going be a hurricane. The system is battling too much in the way of dry air right now. And there's another storm coming across from Africa right now that looks like by this weekend it could get its act together and be the next named storm. We'll see. And we got another system right off the coast of North Carolina right now that's a tropical depression. I'm not expecting much out of that one, although it eventually could get named as well.

CURWOOD: And what's the risk of the Gulf folks getting innundated again?

MASTERS: Louisiana looks like it's going to be off the hook on this one, however, Florida's going to get nailed pretty hard. We're expecting 10 or 15 inches of rain over the next week from this tropical depression that's in the Gulf of Mexico with some isolated amounts up to 15 inches. There's going to be a lot of street flooding. I'm a little concerned about Lake Okeechobee. They'll probably have to start dumping Lake Okeechobee as fast as they can after the storm departs to keep the pressure down on its dikes which are risk of failure when they get too much water behind them.

CURWOOD: And by the way what's the risk of storm surge for Florida? I mean, much of South Florida's only in the scale of a few feet above sea level.

MASTERS: The particular storm surge danger is along the Gulf Coast of Florida where you got a very long area of shallow water extending 90 miles offshore, and just a 50 or 60 mile-per-hour tropical storm can generate a four-foot storm surge. Category one hurricane, we're talking about a 9 to 10 foot storm surge. Category three hurricane, you are looking at a 20 foot storm surge. So, a lot of potential for storm surge along Florida's Gulf Coast. Not as much along the Atlantic Coast because the water is deep in there and you can't pile up as much water near shore.

CURWOOD: I also understand that there's a couple of hurricanes approaching Hawaii as we are talking on the 30th of August. And, Jeff, you've written about how climate disruption may be increasing the number of Hawaiian hurricanes. What's the record in the past and why do you think this could happen now?

Heavy downpours caused record flooding in Baton Rouge, Louisiana in August 2016. Extreme rainfall events are expected to become more frequent as the climate warms, since a warmer atmosphere is capable of holding more moisture. (Photo: Petty Officer 1st Class Melissa Leake / Coast Guard, Flickr CC BY 2.0))

MASTERS: It's really crazy to see two major hurricanes approaching the Hawaiian Islands. They've only ever had five direct hits by either tropical storms or hurricanes since 1949, and two of those hits were in the last three years. And there's two storms that are out there right now, a category three and four. There's never been a case where two major hurricanes have threatened Hawaii, and the reason for the activity over the past few years is just because we crossed a critical threshold. It used to be the waters were not warm enough to the east of the Hawaiian islands to support a hurricane. And just in the past two years those waters are warm enough. Now that's due to a combination of natural patterns which we call El Niño and the PDO or Pacific Decadal Oscillation, but that's combined with the overall ramp-up of global temperatures causing warming of the oceans all over the world. So, now you can get hurricanes that affect Hawaii before you couldn't.

CURWOOD: OK, what is the link between hurricanes and climate change?

MASTERS: Hurricanes are heat engines which means they extract heat energy from the ocean to convert it to the power of wind, and the warmer the ocean is, the stronger a hurricane can get if all other conditions that it needs to exist are present. So, can scientists are confident that as we continue to heat up the oceans, we're going to see more of these high-end perfect storms. The strongest storms are going to get stronger, and we're going to see a few storms with 200 plus miles per hour sustained winds like we saw you last year off the coast of Mexico with Hurricane Patricia. It had sustained winds of 215 mph. That was a world record for the strongest winds ever observed in a hurricane. So we're talking about tornado scale winds on a hurricane scale which means a diameter 20, maybe 30 miles across would get those kinds of destructive levels of damage that we usually only see in a tornado.

Expected rainfall totals across the continental United States from September 1-8, 2016 (posted August 31st), show that parts of Florida and the Eastern Seaboard could get up to 10 inches of rain. (Photo: National Weather Service, CC government work)

CURWOOD: Sounds very scary. Now, you've been in the meteorology business for what 20, 25 years now?

MASTERS: Yeah, 30 years.

CURWOOD: To what extent did you think that you would see the kind of events you're seeing right now when you began your career?

MASTERS: Not at all. I remember in the 80s when I was first a training as meteorologist, it was very cut and dried. I mean, I knew going into winner that we were going to have a couple solid months there in Michigan of below freezing temperatures. Yeah, maybe we would get a little thaw in January where it would get about 40 for a few days, but very very consistent. And that has been totally turned on its head now. I don't recognize the climate anymore. I mean I look at the weather maps in the morning sometimes afraid of what I'm going to see. It's just gotten so insane. The climate of the 20the century is gone. The climate I knew is not here anymore. We're in an entirely new climate regime, and it is extremely intense.

Jeff Masters is the Director of Meteorology at Weather Underground. (Photo: Weather Underground)

CURWOOD: So you’re saying you don't recognize weather patterns anymore, and to what extent do you think that is just going to continue to be this way?

MASTERS: It probably will accelerate for the next couple of decades and then it is my guess that it will level off some. The pace of change right now is at a maximum. The amount of carbon dioxide we're putting into the air is still increasing each year and that's going to keep the acceleration rate of the change in the weather systems going. But at the same time, in a few decades, the ocean temperatures are going to be well beyond what they are now, and we're going to see some really extreme storm behavior I think. Even once it does start to level off, it'll level off at this extreme level that is going to be difficult for society to adjust to.

CURWOOD: Jeff Masters is Director of Meteorology with Weather Underground. Thanks so much, Jeff, for taking time today.

MASTERS: OK, Steve.

Related links:

- Jeff Masters’ blog on Weather Underground

- FiveThirtyEight: “One Hurricane Is Rare In Hawaii, And The State Might See Two This Week”

- NOAA analysis on the link between climate change and Atlantic hurricanes

- Track storms on the National Hurricane Center website from NOAA

- About Jeff Masters

Gulf Oil Leases Spark Outcry But Little Revenue

Blake Kopcho, right, and John Clark, left, were arrested along with two other protestors at the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) office in New Orleans, Louisiana. (Photo: Louisiana Bucket Brigade)

CURWOOD: With many linking the unprecendent floods in Louisiana to climate disruption stimulated by rising levels of CO2, a band of protesters in New Orleans recently tried to block the government auction of 4,400 oil leases in the Gulf of Mexico. The Louisiana Bucket Brigade held a sit-in at the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, and although the auction went ahead online, the group's director Anne Rolfes told Living on Earth's Helen Palmer that they got their message across.

ROLFES: We carried the truth to the feet of the oil industry which was that they are in large part responsible for the floods that devastated south Louisiana. We brought mounds of flood debris and made the point that continued oil drilling in our Gulf of Mexico and all over the globe causes floods like these.

PALMER: And you feel that basically you're part of the world, the New Orleans area, Louisiana, is particularly vulnerable to flooding and to storms.

ROLFES: What's interesting about this last flood is that parts of our state that had never flooded before were overwhelmed with water. So, for example, my childhood home in a town called, Lafayette, Louisiana, had water in it. That had never happened. According to the National Weather Service, the air has so much more moisture in it because we have warmed the planet through the burning of fossil fuels, and so that's the thought process behind this idea that drilling is causing the terrible floods that we recently experienced.

PALMER: Now, you wanted to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management to cancel the sale of leases. That didn't happen. But as I understand it, the lease sale wasn't very successful. What exactly happened?

ROLFES: There were not as many bids as there had been in the past on these huge tracts of the Gulf of Mexico that the federal government is offering, and in the recent past this is exactly what's been happening. The oil industry is in what they considered to be a slump. The good news is that means that bids like these are down.

Active BOEM leases in the Gulf of Mexico (Photo: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management)

PALMER: Yeah, there were only 24 out at 4,400 leases actually taken up, and it was a record low amount of revenue offered, that was $18 million. I mean, part of this is because, of course, oil prices are low, but do you think there's anything else going on?

ROLFES: Well, there's no question that the oil industry has some real economic problems facing it. They've got infrastructure out in the gulf that is absolutely falling apart. They are deciding not to repair that infrastructure. They have left, for example, 26,000 wells abandoned in the Gulf of Mexico. So they certainly do have stranded assets, but the only thing that drives this industry is profit. They're not going to do anything because for any other reason there was a rebuttal to our action written by the Louisiana oil and gas industry, and in that rebuttal, they tried to explain how they're helping flood victims and they call us to take for using the flood to attack them, when in fact, when they burn carbon, they melt our planet.

Protestors at the BOEM office sent a message to President Obama asking him to cancel new oil and gas drilling leases on public lands. (Photo: Louisiana Bucket Brigade)

PALMER: Now, your organization, the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, is one of the many organizations that really are supporting the Keep It In The Ground movement. Do you think that that movement is being successful and what you see ahead?

ROLFES: One of the great things about this movement is that we are seeing success on a consistent basis. Several months ago in March we sent 300 people into the auction and delivered a very clear message which was that our Gulf was not for sale. In response to that action in March they've banned the public from these auctions of our Gulf of Mexico. And I think what it shows is that they're quite afraid of public opinion. When we went to their office last week, who was there? Two armed guards. I mean, something is really wrong when you have to start to arm people in order to pull natural resources out of the ground. I mean, we certainly see this in countries around the world in places like Nigeria where I worked for several years, but now it's come to Louisiana. And it's a new day. I think what's ahead is more of the same, that we will continue to defend our natural resources and our homes from an industry that really is a predator.

Anne Rolfes is the Founding Director of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade. (Photo: courtesy of Anne Rolfes)

PALMER: Of course, not everyone in Louisiana is against the oil industry. After all, they do provide jobs. What's your argument for that?

ROLFES: Well, if you compare the tourism sector and the seafood sector of our economy, both of those sectors provide more jobs than the oil industry. That's important because the oil industry damages those sectors. I mean, just think about the BP disaster. What did that do to our oyster industry and to our shrimp industry? It damaged it. The very idea that they want to claim jobs with a serious face when they have decimated our part of the world is really quite insulting.

Related links:

- The No New Leases website

- Press release on the protest from the Louisiana Bucket Brigade

- AP: “4 arrested in protest against federal oil lease sales”

- The Guardian: “Obama’s offshore drilling puts whales and dolphins in peril, group warns”

- About Anne Rolfes

CURWOOD: That's Anne Rolfes, Director of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, speaking with Living on Earth's Helen Palmer.

[MUSIC: Kanye West/Pusha T, “Runaway,” My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, Roc-A-Fella Records/Universal Music Group International.]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Per-Olov Kindgren, “Air On a G-string, Suite For Orchestra No.3 in D Major, BWV1068,” AIR, Johann Sebastian Bach/Kindgren, Villa Luisa Records]

Linking Fracking and Radon

Research has linked fracking for natural gas to an uptick in radon in Pennsylvania homes, some of which exceed the actionable EPA limit 250 times over. (Photo: Steven Depolo, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, and I’m Steve Curwood. You can't see it or smell it, but radon is the second biggest cause of lung cancer in the U.S. after smoking. This radioactive element is a gas at room temperature and can be locked in rock formations, and when wells are drilled for water or oil or natural gas, the drilling can release radon, which can then migrate into buildings. Today, some of the highest radon levels can be found indoors in Pennsylvania and those levels are ticking up. As the Allegheny Front’s Julie Grant reports, some researchers are giving the gas a second look.

GRANT: Radon starts out as uranium, it’s naturally in soil and rocks. As the uranium decays, it becomes radon gas, and can seep into people’s basements. That’s common in Pennsylvania. So it’s no surprise there’s also radon in the Marcellus Shale, the rock formation that sits under much of the state.

CASMAN: The Marcellus is considered to be a fairly radioactive rock.

GRANT: Elizabeth Casman is a researcher in environmental engineering at Carnegie Mellon University. She’s seen the numbers: the Environmental Protection Agency estimates that indoor radon causes or contributes to 21,000 lung cancer deaths each year. So, after fracking in the Marcellus took off in Pennsylvania, its radioactivity kind of freaked Casman out…

CASMAN: The more I was reading about the formation, and the potential for radon in the natural gas, the more nervous I got.

GRANT: Concerned about lung cancer, she bought an electric kettle, and stopped cooking on the gas stove. More and more Marcellus gas is coming into our homes. And it’s bringing up a topic that many experts thought was settled. People like Dave Allard, who have known about radon in homes for a long time.

ALLARD: I’ve been around the block.(laughs.)

GRANT: He’s currently director of the Bureau of Radiation Protection at the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. Allard says the state already knows why Pennsylvania has high radon levels - it’s known since the mid 1980s.

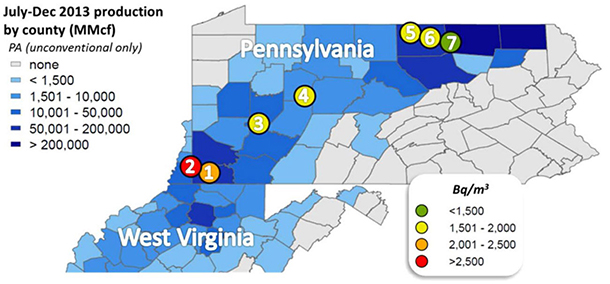

A map of the locations where Carnegie Mellon University scientists collected radon samples. They color-coded each location to describe the calculated concentration of radon. (Photo: courtesy of Carnegie Mellon University)

ALLARD: We have some of the most unique geology, soils and rocks, creating probably some of the highest of radon levels naturally probably in the country, maybe the world…

GRANT: And he says radon in Pennsylvania is trending upward. They’ve seen some homes with levels 250-times the amount that’s actionable by EPA.

ALLARD: And quite honestly some of our residential levels in Pennsylvania, are higher than you would allow in an occupational setting, or a uranium mine.

GRANT: So the DEP looked into it. Bob Lewis is the state’s chief radon officer. He tested at more than 30 wellheads in different regions of the state. At each site, he connected stainless steel cells into the gas well systems.

LEWIS: And then flow the natural gas through the cells for five to ten minutes, and then we do the analysis. And from that, we can then calculate the concentration of the radon in that natural gas at that particular well head.

GRANT: They did similar sampling at natural gas power plants, compressor stations and gas storage facilities.

LEWIS: We collected those samples to make some estimates of the end user.

GRANT: The end user, that’s us, cooking and heating our homes with natural gas. The DEP released his findings in early 2015.

LEWIS: And basically our conclusions, they show that they were receiving small, very small, radiation doses from the radon in natural gas.

GRANT: So, for the DEP, the issue was taken care of. Pennsylvanians are already advised to test for radon in their homes. And Marcellus Shale gas wasn’t adding to the problem. And then, the state’s radon experts got kind of blindsided.

LEWIS: Let me just… I’ve got their, the Hopkins press release right in front of me…

GRANT: Using DEP’s own data, researchers at Johns Hopkins University published a study in Environmental Health Perspectives. The title? “Increased Levels of Radon in Pennsylvania Homes Correspond to Onset of Fracking”. Joan Casey was the lead author. She says her team noticed the upswing in radon happened around the same time as the fracking boom.

CASEY: And we wanted to see if this new industrial development potentially was contributing to increased levels of radon in homes.

GRANT: They broke up the state into different regions - places with no fracking, some fracking, and high levels of fracking.

When people test their homes for radon, the results are filed with the DEP. Casey’s team analysed 860,000 test results in the different regions.

CASEY: We saw at the same time that fracking was going on, increased levels of indoor radon in places that had the most fracking.

GRANT: They also looked more closely at a home or building’s proximity to fracking activity.

CASEY: And we found that buildings that were closer to more drilled wells had significantly higher indoor radon concentrations than buildings located farther away.

GRANT: So needless to say, the DEP’s Dave Allard was pretty ticked by the media attention on this study. He thought Casey’s findings could unnecessarily scare people. One problem, Allard says, is that radon is trending up in every region of the state, no matter how close or far it is from fracking activity.

Elizabeth Casman took steps to minimize her potential exposure to radon when she learned about the radioactivity of the Marcellus Shale. (Photo: courtesy of Julie Grant))

ALLARD: Yea, there’s an uptick. But all of it is upticking through time.

GRANT: So he says there’s got to be a different cause. He’s convinced it’s related to increased soil moisture, and says that’s backed up by a study from Finland, published last year. Casey says her analysis takes rainfall into account. When she looks at her results, and those of the DEP study that found a small increase in indoor radon--she says there’s reason for concern.

CASEY: There’s no safe level of radon exposure, in terms of lung cancer risk. And any increase in radon levels translates into an increased risk of lung cancer. That’s definitely true.

GRANT: Casey doesn’t really know why radon levels are increasing. She says maybe it could be entering homes through well water, ambient air, or the use of natural gas on the stove.Which brings us back to Elizabeth Casman. Remember her? She’s the CMU professor who stopped cooking because she was worried that radon in the gas would increase her risk for lung cancer. Like any researcher, she started gathering data. First, she and her team, wanted to test right the kitchen burner. But that wasn’t easy.

CASMAN: It’s tricky.

GRANT: So, instead, with agreement from energy companies, they took gas samples from pipelines. And Casman says she was relieved by the findings.

CASMAN: We took all the worst cases, and still it came out to a non-scary risk level. And that’s when I calmed down about cooking. I’m cooking again.

GRANT: Casman says unless someone used their unvented stove to heat their home, and they didn’t leave the house for 70 years, they wouldn’t really have an elevated risk of lung cancer from Marcellus Shale gas.

CASMAN: The increment from cooking from the Marcellus only is probably not going to be killing a lot of people.

GRANT: Still, Casman and others want more data. But for now, if you’re concerned about radon from your gas stove, she says, just open a window. I’m Julie Grant.

CURWOOD: Julie reports for the Pennsylvania radio program, The Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Johns Hopkins study linking increased radon levels to fracking

- EPA Radon Information

- Pennsylvania’s Radon Division

- The full Carnegie Mellon study

- Reporter Julie Grant’s Allegheny Front Bio

[MUSIC: King Sunny Ade, “Kita Kita Ko M’ola,” Afropop Stars Salute Africare, Afropop Worldwide/World Music Productions]

Science Note: A Parasite Setback

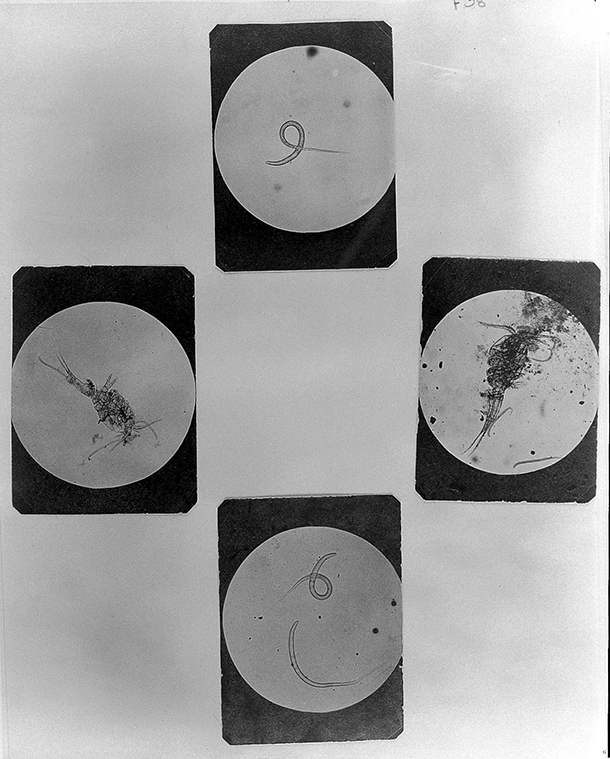

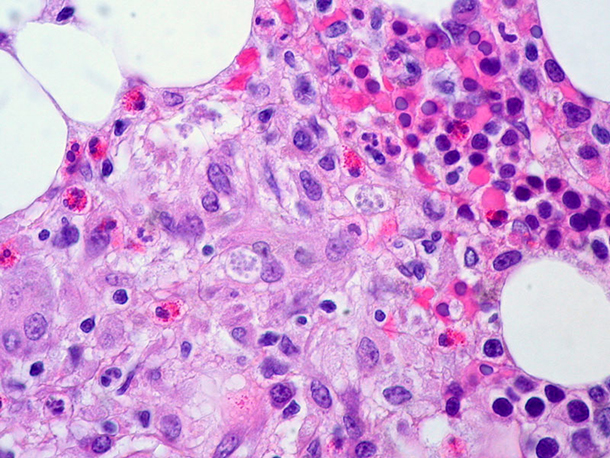

Microphotographs showing development of the guinea worm. (Photo: Wellcome Images, Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Just ahead...new concerns about drug resistant diseases, but first, this note on Emerging Science from Don Lyman.

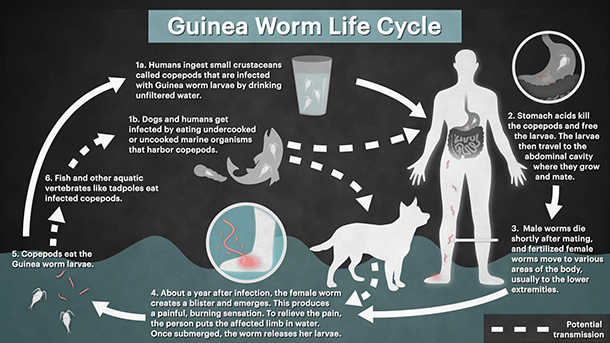

LYMAN: The Guinea worm is a particularly unpleasant parasite. People pick up the larvae by drinking unfiltered water, or by eating undercooked or raw fish. The larvae grow into adults and mate in the abdomen. The worms can grow up to three feet long and emerge through a painful blister in the skin.

The parasite was on the verge of eradication, reduced from about 3.5 million cases in 21 countries in 1986, to just 11 cases so far this year. But now the Guinea worm appears to be on the rebound. The reason? Dogs.

Guinea worm life cycle (Photo: Boston Globe, Hyacinth Empinado/STAT).

In the northern African country of Chad, 498 infected dogs were found from January to May of 2016, a 150 percent increase from the same period last year. And health experts expect infected dog numbers to exceed 600 by the end of this year.

Since dogs roam freely, they can potentially spread Guinea worm larvae to water sources used by humans. The pain when the worm emerges causes the infected host to seek relief in water, where the female worm exits the victim’s body, releases her larvae, and the worms’ life cycle begins again.

So health workers are paying people $20 to keep dogs infected with Guinea worms tied on a leash until the parasite emerges. The Carter Center, which originally helped launch the Guinea worm eradication effort, reported that 81 percent of the 498 infected dogs) earlier this year had been isolated and contained. But that still left 95 dogs which possibly infected water sources.

Scientists and health workers say it’s a big task ahead of them trying to eradicate Guinea worms from dogs, but they believe it can be done within a few years. Then the Guinea worm could join smallpox as the second human disease ever to no longer afflict people.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

Related links:

- STAT News: “Guinea worm, on the brink of eradication, puts up a surprisingly stubborn fight”

- The Carter Center’s Guinea Worm Eradication Program

- WHO: About guinea-worm disease

- CDC: Guinea worm disease

Beyond The Headlines

Fungal infections take about a million lives worldwide every year. (Photo: Ed Uthman, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Time now to join Peter Dykstra to check out what's happening beyond the headlines. Peter's with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org and joins us from Conyers, Georgia. Hi, Peter. Hey, it's nearly fall, but I guess it's still pretty hot there, huh?

DYKSTRA: Still in the 90s and hi, Steve, we haven’t talked in a few weeks, so let’s start off with some fungus.

CURWOOD: Fungus? Why?

DYKSTRA: Well, we hear a lot about antibiotic resistance, and how some dangerous forms of bacteria are becoming virtually immune from the drugs we deploy to kill them off. But there are new concerns about potentially lethal threats from drug-resistant fungus.

CURWOOD: Now usually when we think of fungus, it’s something minor, like athlete’s foot or something.

DYKSTRA: Yeah but not always. We’ve been increasing the use of fungicides on crops, and researchers have identified that as a factor in the potential rise of drug resistance. Athlete’s foot fungus can make your toes itch, but an aspergillus infection could go straight for your nervous or immune systems. Some estimates tell us that fungal infections may already claim a million lives per year worldwide, and they also threaten an iconic food source.

CURWOOD: Oh, which one?

DYKSTRA: Well, a fungus called Black Sigatoka is taking aim at the Cavendish banana – the banana that’s found in just about every market and kitchen in the U.S. To date, the only way to battle Black Sigatoka is of course, increased fungicide spraying. I saw one estimate that fungicides represent about 35% of the cost of growing a banana.

CURWOOD: Ouch, hey, what else do you have?

DYKSTRA: A little medley of ocean oddities from the northeast U.S. coast. A little bait fish called the peanut bunker made itself very obvious in a few New Jersey harbors in late August. Huge schools of them were chased into shallow water by predators, possibly bluefish. There tends to be less oxygen in shallow, warmer ocean water, and with all those fish yearning to breathe free, they suffocated, leaving a mess that had to be cleaned up with front-end loaders and dump trucks, not to mention a horrible smell. Next stop, the Connecticut coastline.

CURWOOD: That’s closer to home for Living on Earth, what’s happening there?

DYKSTRA: Well it’s what isn’t happening nearly as much - lobstering. Warmer waters are the key factor in driving lobster populations as much as 200 miles farther up the coastline. The haul for Connecticut lobstermen peaked at about 3.7 million pounds in the late 1990s, it’s now less than five percent of that, and the news for popular sport fish like flounder and black sea bass isn’t much better.

CURWOOD: But there’s also been one recent arrival, a manatee that’s been hanging around off Cape Cod. How unusual is that to have a tropical animal like that that far north?

Mussel populations have reached critically low levels in the last four decades. (Photo: Drgillybean, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: It’s a little weird, but not completely unprecedented. Some manatees range as far north normally as Delaware Bay in the summer. The last spotting off Cape Cod was in 2009. The big question is whether this one will head back south for warmer waters before winter. Care for a final bit of east coast saltwater gloom?

CURWOOD: Well, if you must.

DYKSTRA: Scientists report a 60 percent decline in mussel populations in the Gulf of Maine in the last 40 years. Blue mussels are a popular seafood on the plate, and in the ocean these filter-feeders help keep the water clean.

CURWOOD: So what kind of link might there be to warming ocean temperatures?

DYKSTRA: That’s less certain. Could be warm water, overharvesting, and possibly ocean acidification could be at play.

CURWOOD: It’s been a weird year here along the East Coast indeed. Hey what do you have from the history vault this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, let’s take a quick look at a couple of big anniversaries from the past few weeks. Five years ago, solar company Solyndra failed, taking a half billion dollars of Federal funding with it. The aroma of scandal around its fate became a blunt instrument for clean energy foes to try and beat down new sources of energy.

CURWOOD: I’d say it was more of a sharp spear than a blunt instrument. What else?

DYKSTRA: Fifty years ago the International Whaling Commission, long regarded as a rubber-stamp for the whaling industry, banned the hunting of blue whales, the biggest animals we’ve got, while we’ve got them. A half century later, they’re still gravely endangered, spread so far apart across our oceans that some scientists say blue whales have trouble even finding each other to reproduce.

Blue whale numbers have dwindled since the first half of the 20th century due to excessive hunting. (Photo: David Slater, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Yes, blue whales usually travel alone but a pair were recently sighted together off the New Hamphire coast last week, and I believe that’s very rare.

DYKSTRA: One more anomaly in the Atlantic, and hopefully huge news for a huge species.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks Peter, we'll talk to you soon.

DYKSTRA: OK, Steve. Thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- The Guardian: “Millions at risk as deadly fungal infections acquire drug resistance”

- Sequencing the DNA of banana fungus

- Dead peanut bunker wash up on New Jersey shore

- Connecticut lobsters are moving north with climate change

- Cape Cod manatee sighting

- Decline in New England mussel populations

- Blue Whales spotted off coast of New Hampshire

BirdNote: The Zone-tailed Hawk

The Zone-tailed Hawk (right) and Turkey Vulture (Photo: Eric Bruhnke)

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

CURWOOD: Vultures may not be everybody's favorite birds, as they are seen picking at dead things. But as Michael Stein explains in today's BirdNote®, for one American hawk, vultures can provide useful cover.

[Zone-tailed Hawk cry, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/140253, 0.15-.18]

STEIN: The Zone-tailed Hawk of the American Southwest looks a lot like a Turkey Vulture. It’s dark all over, has a long tail, and soars on long, upward angled wings while tilting from side to side. And – this is where it gets intriguing – Zone-tailed Hawks often soar among groups of Turkey Vultures.

But there’s a crucial distinction between the two, especially if you happen to be a dove or lizard exposed on the terrain below. While the vultures are searching for carrion, the Zone-tailed Hawk in their midst is hunting live prey.

[Zone-tailed Hawk cry, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/140253, 0.15-.18]

Zone-tailed Hawk (Photo: Tim Lenz, CC BY 2.0)

By consorting with vultures, a Zone-tailed Hawk gains a distinct advantage as a predator. Because while doves and lizards would quickly flee the flight silhouette of a Red-tailed Hawk, they seem to ignore the shadow of a vulture overhead, a bird that poses no threat. So floating among the vultures, a Zone-tailed Hawk is a sort of wolf in sheep’s clothing – and can sneak up on its prey undetected.

Just how Zone-tailed Hawks developed this relationship with Turkey Vultures isn’t clear. But we do know that Zone-tails occur only within the geographic range of vultures. And they don’t just soar with them – they also nest and roost near their scavenging accomplices.

[Zone-tailed Hawk cry, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/140253, 0.15-.18]

I'm Michael Stein.

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. 140253 Recorded by Gerrit Vyn.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

© 2016 Tune In to Nature.org September 2016 Narrator: Michael Stein

http://birdnote.org/show/zone-tailed-hawks-mimic-vultures

Related links:

- Listen to the original story on the BirdNote® website

- More on Zone-tailed Hawks from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

[MUSIC: Paul Winter Consort, “Grand Canyon Sunset,” Canyon, Living Music]

Your Brain On Parasites

A hairworm parasite exits a cricket (Photo: courtesy of Kathleen McAuliffe)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Parasites. They range from microscopic bacteria and viruses to 50 foot long tapeworms. They've been living on us and in us and their other host organisms for millions of years. In her new book, "This is Your Brain on Parasites", author Kathleen McAuliffe describes the numerous links between animals and parasites, how they've co-evolved, and how parasites may actually affect the behavior of humans and other animals. Kathleen McAuliffe joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MCAULIFFE: Pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: Your book is really fascinating, and, well, really requires a whole different way of thinking to absorb it. So we're going to go at this sort of one piece at a time. First, talk to me about trematodes and their relationship with ants and why this shows that these parasites can affect the way that animals behave.

MCAULIFFE: Trematode are basically a parasitic worm, but they have three hosts often, or two hosts, different species, and there's a very interesting case of a trematode that when it gets into an ant's brain it instructs the ant to leave its colony at night and climb to the top of a blade of grass, lock on to it, and just hang there overnight. If nothing happens, it goes back down to the colony the next day and he returns the next evening and he will do that again and again until a sheep comes by and happens to eat that blade of grass with the ant attached, and when that happens the parasite gets into the sheep, specifically into its bile duct, which is exactly where it wants to be because that's the only place it can reproduce.

CURWOOD: So, OK, a couple of questions here. Why is the parasite doing this and if it does do this, why isn't it sending the ant away during the daytime? You would think that the sheep eat during the day as well as night.

Toxocara canis (canine roundworm) from a puppy. (Photo: Joel Mills, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

MCAULIFFE: Because if the ant remains attached to the blade of grass during the daytime, it will fry to death in the noonday sun. So that's why it will go back down to the colony and act like a normal ant during the day, but then it returns it night to reattach to that leaf until it gets eaten basically.

CURWOOD: Amazing. So, in another words, the trematode has taken over the life of this ant.

MCAULIFFE: It's hijacked its behavior.

CURWOOD: Now most people are kind of freaked out about parasites, Kathleen, so what made you want to write a whole book about them?

MCAULIFFE: The genesis of the book was an item I came across one day on the web, a brief article about a parasite that gets into the brains of rats, and it actually can turn the animals innate fear of cats into an attraction, and when I say attraction it actually makes the rodent sexually attracted to the scent of cat odor and so needless to say the rodent soon is back in the belly of the cat which is the only place that this parasite can sexually reproduce. And this so blew me away that I thought, can there possibly be more examples of this? It just seemed so wild. And I started asking around and I found out that there's just scores of manipulations every bit as impressive, and they entail ants, they entail fish, they entail crabs, even mammals, so it's a very broad phenomenon.

CURWOOD: Now, there's a fascinating part in your book where you talk about toxoplasmosis, something that people can get from cats and the evidence that quite possibly this exposure to this parasite can change human behavior. Talk to me about this.

MCAULIFFE: Yes, this cat parasite is the one I mentioned a little bit earlier. I mentioned that there is a parasite that can get into rodents and make them sexually attracted to cats. That is toxoplasma and what happens is after it gets into that cat gut, the cat begins shedding the parasite's eggs in its feces. So we can accidentally be exposed to that when we're change a cat litter box or even sometimes it can happen while you're gardening or if you don't do a really thorough job cleaning vegetables, if you don't get off all the dirt particles, you can be exposed to the parasite that way, and 20 percent of Americans have the parasite in their brain, and a lot of research suggests that in a small percentage of people, we don't know how many, but it can contribute to mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, there's evidence that it increases recklessness and so several studies, independent studies, have shown that people who have the parasite are more likely to be in car crashes. I don't want to terrify people because, remember 20 percent of people are infected and, for example, in the case of schizophrenia 1 percent of the population schizophrenia and the parasite is probably only involved in some percentage of those cases. Some people think as high as 40 percent, others think it is as low as 10 percent or even a few percent, but your risk of being diagnosed with schizophrenia is not dramatically elevated simply because you have this parasite in your head.

Sacculina carcini, a parasitical barnacle on a female swimming crab from Belgian coastal waters. (Photo: courtesy of Kathleen McAuliffe)

CURWOOD: Car crashes? So being exposed to cat feces could raise the incidence of car crashes?

MCAULIFFE: There are a few studies. I know that one of the best studies which was done in Czechoslovakia involved many thousands of participants, and it was a very good study because it was longitudinal. So they first identified people who tested positive for the parasite, and then they followed them over I believe a five or 10 year period, and they showed that yes indeed, the people who had the parasite we're more likely to go on to be involved in car crashes, especially when they were the party at fault.

CURWOOD: And what kind of numbers did they get regarding these traffic accidents?

MCAULIFFE: The people who tested positive for the parasite were 2.7 times more likely to be in a car crash especially crashes where they were at fault.

CURWOOD: Well, that's almost three times as likely. I guess a defense in front of the judge...the cat made me do it.

Kathleen McAuliffe is a science and health writer and has also published articles for The New York Times, Smithsonian, and Atlantic Monthly. (Photo: courtesy of Kathleen McAuliffe)

MCAULIFFE: Nobody's yet used that defense but interestingly enough Stanford Law School actually held a conference to discuss the question of whether toxoplasma could constitute a defense for criminal behavior. The lawyers ultimately decided that the science is not far enough advanced to be used for that purpose, however, they said in capital punishment cases they might actually try to use the infection during sentencing time as a mitigating factor, because apparently in capital punishment cases because basically you know you may pay for a heinous crime with your life, they are not quite as stringent about the kind of evidence that they'll allow to be introduced into consideration.

CURWOOD: Kathleen, how surprised have you been to learn that parasites seemed to have an effect on human behavior in certain cases?

MCAULIFFE: Initially, when I first heard about it, I was very surprised. However, when you understand how some of these parasites work, it isn't so surprising. So, take for example, the parasite toxoplasma. When it gets inside our brains, the neurons it invades, it will crank up their production of dopamine, which is one of our own neurotransmitters. The protozoan itself has genes that allow it to do that, but it does do some things are just so wild and I have no idea how it pulls it off. For example, the same parasite goes into the testicles. It cranks up testosterone production. It causes the rodents to become overly confident, super cocky. That makes them also at greater risk of being caught by a cat. The same parasite can also cause female rats to produce excess progesterone and it has the same effect on them. They become very much emboldened, and nobody knows how they do that. So there's certainly many routes by which this parasite can change behavior. It also just kind of randomly lands often in the brain and if the parasite becomes clustered in certain locations, you can understand why it might, for example, affect your judgement of risk or why it might affect your risk of getting a disease like schizophrenia. If the parasite is sort of randomly scattered, randomly dispersed across the brain, probably you're not going to get many adverse effects, but if it clusters in specific regions, it is easy to comprehend how it might be causing trouble.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about how the parasite that causes malaria causes humans to perpetuate its nefarious mission.

MCAULIFFE: One of the things it does when it infects a person is it introduces an anticoagulant, it's sort of like a blood thinner. So when other insects then feed on that person they can suck more infected blood out of them, and then these little flying syringes can go and infect many more people. Another thing that the parasite does is it, when it gets into a person, it changes their odor; it may actually amplify our scent, and that means that more insects and uninfected insects will then be attracted to the body of an infected person and they will feed on them and then just go spread the parasite to more and more people.

CURWOOD: Kathleen, what kind of stories of been done that demonstrate that the malaria parasite can change human odor?

Toxoplasma gondii, a parasite that infects cats and other mammals, including people. (Photo: AJ Cann, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

MCAULIFFE: There was a very interesting study done in Kenya where they actually put children in tents, separate tents, and they have children who had malaria at a transmissible stage of infection in one tent, and they would have children who were infected but the parasite was not yet at a transmissible stage, and then they had children who were completely uninfected. I wanted to say that all these children were actually protected from being bitten, but they basically released insects into these tents to see if they favored one child over another, and what they discovered is that these insects and they're all uninfected mosquitoes, had a strong preference for the kids that had malaria at a transmissible stage.

CURWOOD: What's your favorite parasite and why?

MCAULIFFE: I think my favorite parasite has to be a parasitic barnacle. Suspend any notions you have about how barnacles look or behave. This barnacle basically injects a clump of its cells into a crab and it just overtakes its whole body. The closest real-life entity to the nightmarish image of a bodysnatcher. This barnacle just all its tissues spread to the inside of the crab and it even sterilizes the crab and then from that moment on, the crab lives and exists solely to nourish the parasite and it will even, when the parasites babies are ready to be born, it will go into deeper water, it will bob up and down and release them send them on their way. So basically, it's a robo-crab.

CURWOOD: Wow, a zombie huh?

The normal spiderweb on the left contrasts with one spun by a spider infected with a parasitic wasp that changes its behavior. (Photo: courtesy of Kathleen McAuliffe)

MCAULIFFE: A zombie crab. The other thing that's important to know about this is lots of these parasitic manipulators are extremely common in nature and they have big ecological implications. So, for example, this parasitic barnacle, they make up 20 percent of all barnacles, and in many parts of the world, these barnacles have colonized huge proportions of crabs. So, for example, in Danish fjords one quarter of the crabs have been colonized by the barnacle. In Hawaii, 50 percent. In many parts of the Mediterranean, 100 percent of the crabs that you see are really a barnacle masquerading as a crab. I call them robo-crabs.

CURWOOD: So those crabs. Are those crabs we eat?

MCAULIFFE: I asked that question to one of the experts because it horrified me to think that one of those crabs might end up on my dinner plate. The parasitic barnacles as I say invades the soft tissues of the crab like a metastatic cancer but then it sterilizes the crab and where the crab would normally grow a brood pouch on its underside, the parasite grows a brood pouch of its own and it’s visible, it’s he only visible portion of the parasite. It's kind of a yellow bladder shaped organ and fisherman look for it, and when they see it, they do not sell those crabs, they just throw them back in the water.

CURWOOD: Yeah, parasites I mean OK, why do we need them? The thought would be that we might just be better off without them if they didn't exist?

A hairworm crawls out of a frog (Photo: courtesy of Kathleen McAuliffe)

MCAULIFFE: A lot of food chains actually would collapse if it weren't for parasites because parasites are basically taking a lot of animals out of one habitat and plunking them down in another. Just give you an example there's not a parasite that gets into fish brains and it makes the fish go to the surface and rollover, it lowers the anxiety of the fish so that they then get eaten. Well, the vast majority of these fish become parasitized by adulthood and these fish are amongst the most common denizens of California estuaries and actually estuaries in many different parts the world. As are the shorebirds that then swoop down to eat them. So, parasites have a profound impact on food chains. And it's a question that a lot of biologists is, “would the world be the same if it weren't for those parasites?” Because they're incredibly common. The cat parasite I mentioned, toxoplasma, it has infiltrated basically every warm blooded animal on Earth. It's in birds and all mammals, it has even invaded the marine ecosystem, so it's in dolphins, it's in whales, it's in walruses on ice sheets. So these parasites have a profound impact on ecology and the world wouldn't be the same without them, and yes, they cause horrible diseases, but nature would not work the same without them. In fact, a parasitic existence is the most common on the planet.

CURWOOD: Well, we could go into politics on that one, but we won't.

MCAULIFFE: [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: So given that parasites are so widespread and affect both animals and humans, what's the message here to the medical community?

MCAULIFFE: It depends of course on the specific parasitic manipulation we're talking about. In many instances, there should be I think, one of the applications is that doctors should be paying more attention to how to prevent the spread of these diseases. So, for example, toxoplasma, the cat parasite, it is often transmitted to children through sandboxes because sandboxes are a favorite place for cats to bury their feces. So simply covering sandboxes when they're not in use is a very good way to protect against the spread of the parasite. I think there also has to be greater awareness of the risk of getting the parasite from rare meat. Cattle can pick up the parasite from the ground and it actually gets into their flesh, the meat that we eat. So if you like rare meat, it does increase your risk of becoming infected like 50 percent of French people have a parasite because they love their meat so rare and “saignant” is literally “bleeding”. If you are one of those people who likes rare meat, then it's wise to freeze it first and then cook it because when you freeze it you kill the parasite.

Kathleen McAuliffe has received awards and fellowships in recognition of her excellence in science writing. (Photo: courtesy of Kathleen McAuliffe)

So I think really the emphasis has to be on protection, but also a lot of money is being invested in developing vaccines possibly for cats to stop the spread of this disease and a group of researchers are also looking at developing drugs that can route the parasite out of the head and they're looking specifically at drugs used to treat malaria because as it turns out toxoplasma is a close relative of the parasite that causes malaria so they're hoping that some of the drugs are effective against malaria may also be useful in treating toxoplasma.

CURWOOD: Kathleen McAuliffe is author the book "This is Your Brain on Parasites". Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Kathleen.

MCAULIFFE: It was a pleasure.

Related links:

- The Atlantic: “How Your Cat Is Making You Crazy”

- CDC: About the parasite toxoplasmosis

- CDC: About the parasite toxocariasis

- About the parasite barnacle Sacculina

- About Kathleen McAuliffe

[MUSIC: Nick Brignola and Sal Salvador, “Walk On the Water,” A Tribute To Gerry Mulligan, Gerry Mulligan, Stash Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Emmett Fitzgerald, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. We wish a fond farewell to our hardworking interns Jake Feinstein, Anica Green and Charlotte Rutty. Thanks for all your creativity this summer. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on Facebook - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth