October 7, 2016

Air Date: October 7, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Trump on Climate

View the page for this story

The comments of Republican Presidential nominee Donald Trump on global warming demonstrate inconsistency and his campaign has been unwilling to discuss with Living on Earth his stands on environment and energy issues. Host Steve Curwood compares various statements of Mr. Trump and his running mate Gov. Pence, and talks with Politico Reporter Ben Schreckinger about the campaign. (11:30)

Paris Agreement Becomes International Law

View the page for this story

The Paris Climate Agreement has reached the key threshold of ratifying parties to enter into force before the UN’s November Conference of the Parties in Marrakech, Morocco. Prof. Robert Stavins, head of the Harvard Project on Climate Agreements, puts this achievement into context with host Steve Curwood and previews the many tasks negotiators and nations face as the Paris Agreement officially becomes international law on November 4. (00:08)

Game-Changing Rules for Endangered Species

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Every three years or so, the Convention on International Trade Of Endangered Species meets to determine the best way to protect plants and animals traded across borders. Living On Earth’s Bobby Bascomb attended the 2016 conference, and host Steve Curwood caught up with her to discuss the negotiations, the disagreements, and the creatures that gained stronger legal protection against poachers such as pangolins and grey parrots. (07:45)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip Beyond the Headlines, Peter Dykstra laments with host Steve Curwood the potential loss of several iconic ecological treasure spots and provides an update on sexual harassment charges against the National Park Service and other science institutions. For the weekly history lesson, he recalls partial meltdown of the Fermi nuclear power plant in Michigan, kept secret for years. (00:03)

BirdNote: When the Amazon Floods

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Floods can be devastating and destructive, but in the Amazon, as Mary McCann notes, annual floods are vital for many exotic bird species. (00:02)

The Hidden Life of Trees

View the page for this story

Forests contain much, much more than meets the eye, writes Peter Wohlleben in his groundbreaking book The Hidden Life of Trees. Within the roots of trees are active brain-like processes, and trees are capable of communication and learning. A forester himself, Peter Wohlleben tells host Steve Curwood about the unseen and unsung connections between trees, and how humans can better care for them. (00:14)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Ben Schreckinger, Robert Stavins, Peter Wohlleben

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Presidential hopefuls and the environment. This week Mike Pence and the evolving stance of the Republican National ticket on climate.

PENCE: There's no question that the activities that take that activities that take place in this country and in countries around the world have some impact on the environment and some impact on climate.

CURWOOD: Trump, Pence, energy, the environment and more. Also, the Paris Climate Agreement becomes international law, and America has reason to celebrate.

STAVINS: What the United States has wanted was an international agreement which would not be dictating what we would have to do, and which would include the large emerging economies of China, India, Brazil, and Mexico. We've got it. The United States has actually won.

CURWOOD: The national and international politics of global warming. We’ll have that and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Trump on Climate

The Republican nominee for President, Donald J. Trump, has tweeted, "the concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive". (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. As the US national elections draw near, we’re taking a look at the environmental records and plans of the presidential candidates. Today we’re examining the beliefs and ideas of the Republican presidential nominee, Donald J Trump and his running mate, Indiana Governor Mike Pence, and they don’t always seem to agree. To get a clearer picture we requested interviews with Mr. Trump and Governor Pence, which were denied by Trump press secretary Hope Hicks. And the Trump ticket did not offer any surrogates. So we approached Myron Ebell, long a prominent denier of the human role in climate change, whom the Trump campaign has reportedly designated as the transition team point person regarding the Environmental Protection Agency. He declined to speak with us as well, referring us back to the campaign, so we decided to look at the record. On September 27th, Vice Presidential candidate Mike Pence was a guest on Chris Cuomo’s “New Day,” a CNN cable news program, where he said,

PENCE: There's no question that the activities that take place in this country and in countries around the world have some impact on the environment and some impact on climate.

CURWOOD: The internet and press commentary blew up, noting that the candidates are not on the same climate change page. This was a flip for Governor Pence. He’s called climate change “a myth” in the past, and it’s especially surprising when you consider what campaign manager KellyAnne Conway said of Mr. Trump’s beliefs right before on another CNN program.

CONWAY: He believes that global warming is naturally occurring.

REPORTER: Is what...naturally?

CONWAY: That climate change is naturally occurring.

REPORTER: He believes in climate change.

CONWAY: That there are shifts that are naturally occurring.

REPORTER: Oh, he doesn’t believe it’s manmade.

CONWAY: Correct.

CURWOOD: This is a claim Donald Trump himself has repeated on national television.

TRUMP: Well, I’m not a big believer in man-made climate change. It could be some impact, but I don’t believe it’s a devastating impact.

CURWOOD: Oh, and by the way, not only is there inconsistency between Governor Pence and Mr. Trump, Trump and Trump don’t always agree on his climate change statements either. This is from the first presidential debate on September 26th.

HILLARY: Some country is going to be the clean energy superpower of the 21st century. Donald thinks that climate change is a hoax perpetrated by the Chinese. I think it’s real.

TRUMP: I did not...I do not say that. I do not say that.

CURWOOD: In his Tweets, Mr. Trump notes, for example, “Snowing in Texas and Louisiana, record-setting freezing temperatures throughout the country and beyond. Global warming is an expensive hoax!”

As Governor of Indiana, Vice Presidential Nominee Mike Pence wrote that climate change is a “myth”, a statement he countered in a CNN interview September 27 stating that humans do have some impact on the climate. (Photo: YouTube screenshot)

CURWOOD: We could not find mention of climate issues on the Trump campaign website, but it does offer an "America First" energy platform that pledges to "make America energy independent, create millions of new jobs, protect clean air and clean water, and conserve our natural habitats, reserves and resources". But it offers no details as to how that would all be accomplished. Mr. Trump has been critical of President Obama’s decision to halt the Keystone XL pipeline and blames the President for “killing the coal industry”. Mr. Trump also wants to cancel the Paris Climate agreement and rescind Obama’s Clean Power Plan.

For more insight we turn now Ben Schreckinger of Politico, who last May told Living on Earth how Mr. Trump had cited the risk of rising sea levels due to climate change, in seeking permission to build a wall for a seaside golf course in Ireland.

Hi Ben, welcome back.

SCHRECKINGER: Hey, glad to be here, thanks for having me back.

CURWOOD: Great to have you back on the show, and of course, both of us have gotten thrown out of Trump rallies, or rather admitted. I think they didn't like your reporting and they invited me, but then when I got to the door, suddenly my name wasn't on the list.

SCHRECKINGER: The Trump campaign has gone further than any American political campaign at a high level in memory, in terms of alienating the press, targeting the press, seeking to block access of the press to its events. As a working journalist, you never want to see that, and so, you know, as someone who’s shared that experience of being kicked out by the campaign, I wouldn't take it personally.

CURWOOD: So tell me, why is the Trump campaign so apparently uncomfortable speaking their views on climate change with the media?

SCHRECKINGER: This is a pattern we've seen on a number of issues with Donald Trump. There seems to be a desire to telegraph multiple, often contradictory messages, and one, you know, let people be confused and let people hear, I think, they're hoping what they want to hear. Donald Trump in the past has been one of the most prominent and outspoken climate change deniers in United States, trumps up public climate change denial, and what he's done in private with his businesses, it’s something that I think has never been fully addressed by the campaign. That was the subject the last time I came on your program.

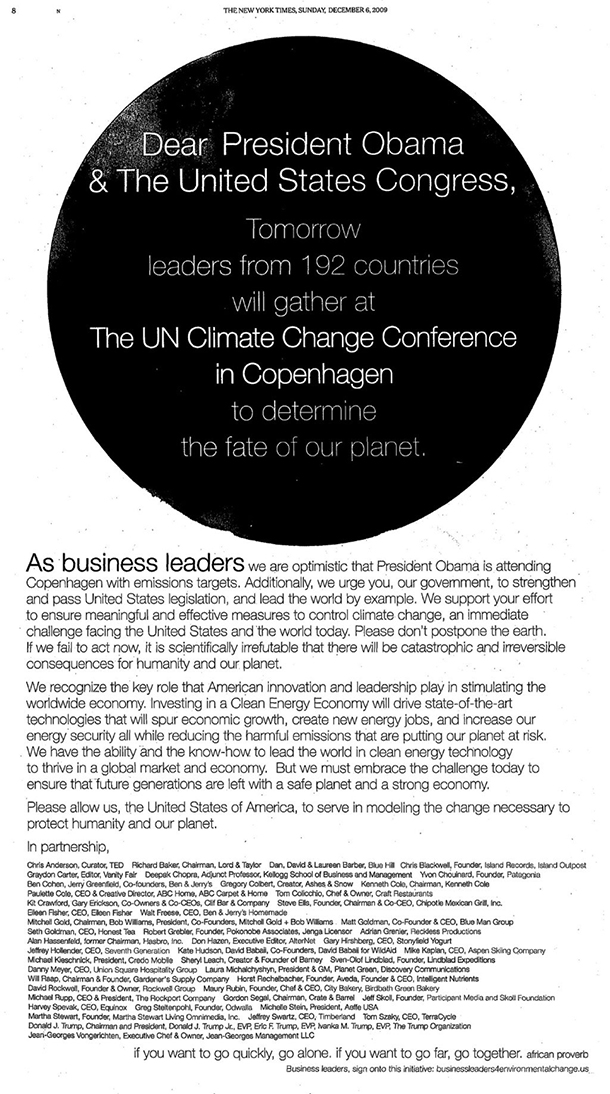

Filing to a county council in Ireland to get a seawall built, Trump identified global warming and the associated increase in stormy weather as a reason to build the seawall, as a vital threat to his resort there. Obviously, there's the hypocrisy question there. Since then, it's also come out there was a full page ad that I think of the New York Times that ran a few years ago, of business leaders calling on the government to take more action on climate change. Trump's three adult children and Trump were all signatories to that, which sort of further muddles his position. It's possible that this was something that his kids took the lead on or a PR firm took the lead on, but it was totally, completely inconsistent with both its denials of climate change then and his position and the position of the people around him that it's really not for the government to take a major role in. There's just a lot of confusion here.

Grist reporters Ben Adler and Rebecca Leber uncovered a full-page ad in a December 2009 issue of the New York Times in which Donald Trump was one of the signatories calling for climate action. (Photo: New York Times)

CURWOOD: So, tell me, why has his vice presidential running mate Mike Pence changed his views from outright climate denial to a view that offers some concessions to the human impacts of climate science?

SCHRECKINGER: That's a real head-scratcher for me. Pence was a staunch ally of the coal industry, of the Koch Brothers. He remains opposed to the EPA's Clean Power Plan. He's been a climate change skeptic. In the past, recently after Trump's campaign manager Kelly Anne Conway said that Trump was skeptical that human activity was contributing to climate change, Pence went on television, I think the next day, and said that human activity does have some impact on the climate. As far as I know, that's the first time he said it, and it's really a bizarre time to change your position when you're contradicting the campaign manager of your presidential campaign. I don't know why he said that, especially when he said it.

CURWOOD: Well there've been a lot of head-scratching moments in this campaign, and I guess when it comes the climate that’s certainly one, isn’t it.

SCHRECKINGER: It’s clear that there's more conversation to be had, more questions to be asked of this campaign in terms of where exactly they stand on climate change and what exactly they think ought to be done with it.

CURWOOD: Well, as we record this on October 5th, there has yet to be any real pressing in the presidential debates, including the vice presidential debate on the climate matter from that hosts. So far we've seen Elaine Quijano and Lester Holt. So, they're not being asked about this.

SCHRECKINGER: And we know that it's an issue that policymakers, thought leaders are very concerned about. We know that the Pentagon views it as a top strategic threat to the United States because of the expectation that the disruptions caused by climate change are going to create national security issues going forward all around the world. We know that Americans increasingly in polls are saying it's something they are concerned about. We know it's a major issue for young people, for people my age, so you’ve got to hope that it's going to get some airtime at a debate.

CURWOOD: Ben, from your perspective, why do you think Mr. Trump's opponent, principal opponent, Secretary Clinton, hasn't pressed on the matter of environment in these debates, at least so far at the time we're recording this. For example, in the vice presidential debate, Tim Kaine, Senator Kaine, just mentioned the prospect of clean jobs and Pence only referred to the climate indirectly complaining about the "war on coal". Why is this so sotto voce? Why not a more vigorous debate?

SCHRECKINGER: Well, that's a good question, and Hillary Clinton is not doing as well as she would like to be with young people, not that they're flocking to Donald Trump, but in really significant numbers millennial voters are looking at Gary Johnson and to a lesser extent Jill Stein. It's possible she could win some points by pointing to her record on that, pointing to her positions on that. I think the reason that she had hasn't is that it's just not a priority. It seems that the priority in these debates is to question Trump's character, make it about his personal fitness for office, beat him into lashing out and, in general, politicians who think that climate change is important have struggled to make it a winning campaign issue, have struggled to demonstrate that there are votes to be had there.

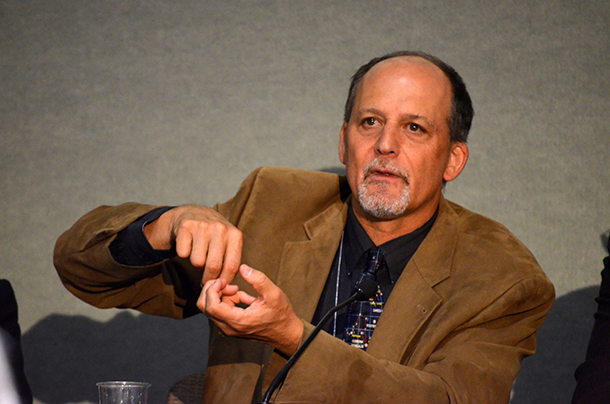

Ben Schreckinger is a reporter with POLITICO (Photo: courtesy of M. Scotty Mahaskey)

CURWOOD: So, what does it do for a democracy with such pressing issues, say around the environment as climate disruption, to not allow the press in, do you think?

SCHRECKINGER: It's never good to be the limiting the access of reporters to a very high-stakes presidential campaign. That's just not the way our system works. Our system is based on protecting the press, empowering them to get as much information as possible about public figures, people who seek to become government officials, and I think that the position of almost any working journalist is going to be, “more transparency, the better,” and taking unprecedented steps in a presidential campaign to block press access is not a good thing for our political system.

CURWOOD: But who needs the press when you've got Twitter?

SCHRECKINGER: Platforms like Twitter do change the balance of influence between the organized press and the presidential campaign. It does erode the gatekeeper function. In some ways that's probably a good thing. It means that there is more direct communication between public figures and the public, more instantaneous communication.

At the same time, novel forms of communication can be exploited. We've seen on Twitter as well, the use of political bots at an unprecedented level for an American election as this sort of thing, these fake Twitter bots that spew propaganda had become common in Latin America, Russia, Syria, and now all of a sudden they're being used in the United States like we've never seen before.

CURWOOD: Ben Schreckinger is a reporter with Politico. Ben, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

SCHRECKINGER: Yeah, thanks for having me, Steve. Any time.

Related links:

- Donald Trump’s “America First” Energy Platform

- Governor Mike Pence’s climate change comments

- Trump says global warming is not human-caused

- Campaign Manager Kellyanne Conway defends Trump

- Ben Schreckinger reports for Politico

- Schreckinger on the climate threats to a Trump golf course

[MUSIC: Lawrence Blatt, “Park Lane,” Longitudes and Latitudes, LMB Music]

CURWOOD: Coming up...it’s official, the Paris climate agreement is now international law, and the US is locked in, no matter who wins the White House. So, stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Tony Bennett/Bill Charlap, “The Last Time I Saw Paris,” The Silver Lining: The Songs Of Jerome Kern, Columbia Records a division of Sony Music Entertainment]

Paris Agreement Becomes International Law

The European Parliament’s approval of allowing member states to officially join the Paris Agreement pushed the landmark climate accord over the critical threshold to allow it to enter into force. (Photo: © European Union 2016 - European Parliament, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. The formal ratification of the European Union on October 7 brings the Paris climate agreement above both thresholds needed to come into force. More than 70 nations representing over 56 percent of total global warming emissions have now acceded, to use the formal word, and in 30 days it becomes international law. That’s just in time for the Agreement’s first meeting of the parties beginning November 7th, as part of the UN climate treaty summit in Marrakesh. Then each ratified country’s Intended Nationally Determined Contribution – or INDC – will be formally registered. It’s no accident that date was chosen, according to Robert Stavins, the Kennedy School professor who directs the Harvard Project on Climate Agreements, and Rob Stavins joins us now.

Welcome back to Living on Earth.

STAVINS: It's good to be back with you.

CURWOOD: So, why was it especially important for the Paris agreement to become international law, to enter into force at this moment?

STAVINS: Well, the reason why it's actually particularly important is because of the US presidential election. The Republican candidate, Mr. Trump, he has phrased it once that he would walk away and other times he has said he would renegotiate the Paris agreement, but it appeared that what he would do be something on the order of rescinding the INDC that was submitted, which, if the Paris Agreement had not yet come into force, the administration could do that, they could change it at any time. But, given that the Paris agreement is now coming into force, the reality is that there are rules about being removed from this international agreement.

Although President Obama -- seen here at COP21 in Paris -- will leave office this January, the U.S. role in the Paris Agreement is secured no matter which candidate is elected to the White House. (Photo: Benjamin GeCOP PARIS, Flickr public domain)

After a country announces its intention to leave the agreement, there is a delay of three years before the process starts, and then the process itself takes one year. In other words, it’s a total of four years. That mean that, if the agreement has already come into force, it would be impossible for a President Trump to remove the United States during what would be his first term; therefore, there was a tremendous amount of enthusiasm and interest around the world, to make sure that the Agreement came into force this calendar year, essentially before Inauguration Day.

CURWOOD: Now that this has come into force, it means that Marrakesh will be able to assemble the meeting of the parties, what is expected to happen at the first Meeting of the Parties of the Paris climate Agreement?

STAVINS: Well, it means that in Marrakesh, that they'll begin to get down to the difficult work of putting flesh on the bones of the Paris agreement. I mean, the way I think of these is that these international agreements -- In this case, what is it? About 13 pages long -- is not very different than the preamble of a statute that has been passed by the Congress and signed by the President. But then there're the hundreds and hundreds of pages that come after it. There are the regulations that have to be promulgated in order to have a statute have any kind of effect. That's what is going be taking place starting in Marrakesh. And the reason why it's significant, it’s actually very impressive, is that the same threshold for it to come into force applied in the case of the Kyoto Protocol, 55 countries representing a minimum of 55 percent of global emissions. It took fully five years after 1997 for that threshold to be accomplished, and this time it's happened in less than a year, so it means they are going to be able to get to work much more quickly than otherwise would have been impossible on the real meat of the agreement.

Among the 28 European Union member states, Poland is finding it particularly difficult to reduce its emissions. Approximately 85% of its energy comes from coal, burned at power plants like the massive Bełchatów Power Station (above). (Photo: VLLI, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the major rules of the Paris Agreement that negotiators are going to have to resolve.

STAVINS: So, there are a whole set of issues that are going to have to be dealt with certainly in terms of reporting and verification. What's the role of the Secretariat of the United Nations framework convention on climate change? How will they do that? This stock-taking that is supposed to happen every five years, where they add up what's been accomplished and what hasn't been accomplished, what's the procedure for that? How will they ensure, if possible, what is a promise of the Paris Agreement, and that is that each five years when the parties, the 197 countries, submit a new Intended Nationally Determined Contribution, how will they ensure that it actually is more ambitious? And then there are a set of very difficult issues around what's been controversial in the Paris agreement and that is Article 6, which is where carbon markets under the new Agreement, that's where they would fall, and a tremendous amount of work is going to have to be done to make that a reality.

CURWOOD: Now, since not every country that signed the Paris agreement has gone through the ratification process to have a seat at this meeting of the parties, how will decision makers ensure that the agreement is inclusive of all the parties, including those who haven't gone to this ratification process at home yet?

STAVINS: Well, that's a difficult one. Had it been that the European Union was not able to ratify the agreement in time, then the delegates were already clear that they were going to make sure that Europe was informally involved, and they'll do the same with other major countries.

CURWOOD: So that means “observer” status?

STAVINS: That's correct. I mean, remember that was the status of the United States and still is under Kyoto.

CURWOOD: Indeed. We don't get to deliberate, but we can watch and comment even.

Before countries could ratify, they had to sign the Paris Agreement document. Secretary of State John Kerry signed for the United States on Earth Day 2016 at the United Nations headquarters in New York. Delegates from 174 nations signed that day. (Photo: U.S. Department of State, Flickr public domain)

STAVINS: That's right, and one can have a lot of influence whether or not one actually casts a vote certainly.

CURWOOD: So, how pragmatic is the Paris Agreement, given that the Intended Nationally Determined Contributions those INDCs don't get is terribly close to keeping warming to below two-degrees Celsius?

STAVINS: Well, actually if I had to choose one word to describe the Paris agreement, it would be the one you just used, Steve. I would say it's “pragmatic”. It's not the type of aspirational agreement that the Kyoto protocol was. It is pragmatic. It is based upon what's politically feasible in each of the countries. That's the whole nature of this hybrid architecture of combining top-down elements for monitoring, reporting, verification, and coordination with bottom-up elements of each country saying not what it hopes to do and then going back home and trying to get it through the Parliament or the Congress, but starting with what it believes it can do and then submitting that as their INDC. Where these things really bind is domestically, at least in a representative democracy.

Robert Stavins is the Albert Pratt Professor of Business and Government at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. (Photo: Harvard University)

What's binding are the set of individual policy elements which is what the Obama administration and a Clinton administration would use in order to achieve the numbers that are in the INDC, the 26- to 28-percent below 2005 level of emissions.

CURWOOD: So this is all about what a country can do on its own, as opposed to being required internationally.

STAVINS: That's right. I mean, there is not a requirement to accomplish particular targets. There are requirements essentially to participate and to submit the numerical targets.

CURWOOD: Now, some people are concerned that the US is really giving up a fair amount of sovereignty, this is moving us towards world government. Your response?

STAVINS: Oh, my response to that is that the United States has won. If anything, other countries might complain that exactly what the United States has wanted for, I’d say, the last 10 years or more. You can go back into the George W. Bush administration. What the United States has wanted was an international agreement which would not be dictating to us what we would have to do numerically, and which would include on an equal footing, not just the United States or the Europeans and the other industrialized countries, but the large, emerging economies of China, India, Brazil, Korea, South Africa and Mexico. We've got it. The United States has actually won.

CURWOOD: Robert Stavins leads the Harvard Project on Climate Agreements and is a professor at the Kennedy School of Government. Thanks so much, Rob, for taking the time with us.

STAVINS: It's always a pleasure to be with you.

Related links:

- Paris Agreement Status of Ratification

- The significance of “CMA1”, the first meeting under the Paris Agreement

- Read Robert Stavins’ blog, “An Economic View of the Environment”

- About Robert Stavins

[MUSIC: Tony Bennett/Bill Charlap, “The Last Time I Saw Paris,” The Silver Lining: The Songs Of Jerome Kern, Columbia Records a division of Sony Music Entertainment]

Game-Changing Rules for Endangered Species

Ivory seized from poachers in Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo. (Photo: ENOUGH Project, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Experts estimate traffickers in illegal wildlife take in some 19–odd billion dollars each year. The illegal wildlife racket is so lucrative that many endangered species face extinction, unless it’s stamped out – and that’s the aim of CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. The Convention meets every two or three years, and delegates from 182 countries have just wound up a meeting in Johannesburg, South Africa. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb was there as well and she joins me now to give us the highlights.

Hi there, Bobby.

BASCOMB: Hi, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, what happened at CITES this year?

BASCOMB: Well, close to 500 different species of flora and fauna were on the agenda, including some really fun species such as the psychedelic rock gecko, the tomato frog, the false tomato frog, several species of sharks and rays. And then there’s the African gray parrot and the Chinese crocodile lizard, which both got moved from the less restrictive CITES Appendix 2 to the more restrictive Appendix 1, which means international trade for those species is now completely prohibited. And trade is also now prohibited for the world’s most heavily trafficked mammal, an animal most people have probably never heard of.

CITES is a triennial conference that assesses how best to protect endangered species caught in the international trade circuit. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: Wait, I think I actually know this. It’s the pangolin, right?

BASCOMB: That’s right, yah. There are eight species of pangolins but they all look pretty similar…. kind of like an anteater covered in scales. They roll into a tight ball when they’re threatened, which makes them easy pickings for poachers.

CURWOOD: The most heavily trafficked mammal in the world… so, why are they such a commodity?

BASCOMB: Well in Asia pangolin meat is considered a delicacy, and Asian consumers believe its scales have special medicinal qualities, which is a widely debunked claim.

CURWOOD: But now pangolins will have a higher level of protection?

BASCOMB: That’s right. In a nearly unanimous decision, CITES delegates voted to completely stop all international trade.

CURWOOD: Now, what about the big African animals everyone loves – you know the elephants, the rhinos, the lions?

BASCOMB: Well, all of those animals have a similar story. They’re caught in a conflict between the “haves” and the “have-nots”. Take elephants for example. South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe all have large, healthy populations currently on the less tough CITES list, so they can be traded but with restrictions. There’s currently a ban on the international ivory trade but Zimbabwe and Namibia introduced a proposal that would make it easier for them to sell their ivory. Edna Molewa, South Africa’s Minister of the Environment supports their proposal.

Pangolin trade persisted before the recent ban because their scales are believed to contain medicinal qualities, and some Asian countries consider their meat a delicacy. (Photo: Mark Simpson, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

MOLEWA: The issue here is about managing these populations of ours in a manner that will actually bring sustainability to vegetation but also getting the needed funding for paying for the conservation functions.

BASCOMB: So, Steve, basically she’s saying that CITES needs to consider carrying capacity. How many elephants can any given piece of land sustainably support? But then you have to remember the elephant ‘have not’ countries. A new elephant census released at CITES shows a 30-percent decline in elephant populations across Africa from 2007 to 2014. In some countries like Cameroon, poaching is such a problem that elephants may go locally extinct there in the near future.

CURWOOD: Wow.

BASCOMB: Yeah, so a coalition of 13 countries with dwindling elephant populations put forward a counter proposal to list all savannah elephants under the toughest controls.

CURWOOD: So, what happened?

BASCOMB: Well, both proposals failed to get a two-thirds majority, so neither passed. Part of the reason the tougher listing proposal failed is that Namibia said that, if their elephants were listed like that, they would invoke what’s called a reservation. Sabri Zain of Traffic, a wildlife trade monitoring group, explains what that means.

ZAIN: This means that legally as far as they are concerned this listing does not apply to them. ‘Cause that will allow these countries to sell their ivory to whoever wants it without any controls or without any measures as that are in place right now under the Appendix 2 listing.

CURWOOD: So, that could be pretty bad for elephants in those countries.

BASCOMB: Oh for sure. And, you know, this clash we’re talking about between the “have” and the “have-not” nations extends to other species here in Africa as well. Take lions, for example. Today lions exist in less than 10-percent of their historical range, so countries with struggling populations like Chad, Ivory Coast, Mali, they proposed to transfer all lions to the toughest list, but countries with healthy populations like Zimbabwe and South Africa oppose that. South Africa actually exports lion bones to China for traditional medicine.

CURWOOD: Yeah, lion hunting is big business for both those countries, isn’t it?

BASCOMB: It is. Usually they use captive, bred lions in what’s called a “canned hunt”. Hunters can pay upwards of $35,000 to kill a lion, money which is supposed to go back into conservation and support local communities. But some CITES countries oppose these canned hunts and want them banned, or at least a ban on the export of lion heads, the trophies from hunting.

So, that debate was contentious but the Secretary General of CITES, John Scanlon, he told me that he thinks there’s room for compromise.

SCANLON: There’s a recognition amongst countries that perhaps don’t like trophy hunting that there are circumstances where that’s very important for local economies and for countries that perhaps rely upon that for their conservation revenue. We’re probably looking more here at how we better regulate it.

Poaching African elephants for their ivory contributed to a 30% population decline over a period of seven years, between 2007 and 2014. (Photo: Brittany H. Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: And that’s exactly what happened. Countries voted to prohibit the export of wild lion parts but allow export of bones and trophies from captive, bred lions.

CURWOOD: Now, what happened at the CITES meeting with rhinos? I know they are critically endangered.

BASCOMB: Yeah, they are. There’s only about 25,000 African rhinos left in the world, and last year alone more than 1,300 were killed. Their horns are sold in Asia for their supposed medicinal properties, which, like the pangolin scales, are scientifically unfounded. South Africa, the CITES host country, is home to roughly 80-percent of the world’s rhinos, and there’s been an ongoing internal debate here about whether or not to legalize the domestic sale of rhino horn. Rhino farmers within South Africa…

CURWOOD: Wait, “rhino farmer”? That’s a thing?

Rhino Farmers like Pelham Jones (pictured below) advocate for a legal, international rhino horn trade because they believe that rhino horns can be a renewable, ethical resource. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Oh, yeah. Some 6,000 rhinos are owned by private citizens, more than in the rest of Africa combined. They keep their rhinos on private farms and humanely remove the horn every few years. It’s made of the same material as fingernails or hair and can grow back in the same way. Rhino ranchers say it’s a renewable resource, and they’re sitting on a stock pile of horns worth millions. They want to sell that stock pile, but a ban has been in place for nearly 40 years. Pelham Jones, the chairman of the Private Rhino Owners Association says prohibition doesn’t work and it’s expensive to keep rhinos.

JONES: The cost for us to protect those animals from 2009 to 2016 is about $115 million. We desperately need funding to help conserve the species. We get zero government incentives or assistance in our conservation endeavors.

BASCOMB: So the small Kingdom of Swaziland requested to be able to sell their horn stockpile, worth about $10 million. The proposal was turned down, though, because of fears that any legal rhino horn trade would only fuel more poaching.

CURWOOD: So, Bobby, proposals to move endangered species from one list to another sound good, but will it make a difference? I mean, poachers don’t care what list these species are on.

BASCOMB: That’s certainly true but there’s also a lot of discussion of other solutions to these issues, so anti-corruption measures, reducing demand, satellite surveillance, DNA forensics to track these products, and I’ll be reporting on that for you soon, Steve.

CURWOOD: Looking forward to it, Bobby. Thanks.

BASCOMB: Thank you, Steve. Nice talking with you.

CURWOOD: That’s Bobby Bascomb, reporting from Johannesburg, South Africa.

Related links:

- CITES conference proposals

- Traffic, the wildlife trade monitoring network

- The Private Rhino Association

- More information on pangolins

- Recent hits to the African Elephant population

- Living on Earth recap of CITES 2013

[MUSIC: Vusi Mahlasela, “Say Africa,” Say Africa, Dave Goldblum, ATO Records]

Beyond The Headlines

The Amazon rainforest is one of the planet’s many ecological treasures that are at risk of being lost to climate disruption. (Photo: CIFOR, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let’s join Peter Dykstra of Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org now to see what he’s found beyond the headlines. He’s in Conyers, Georgia, and on the line.

Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. There was an intriguing little photo essay in Conde Nast Traveler last week about climate change.

CURWOOD: Conde Nast Traveler? That’s not exactly a go-to place for climate change news.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, except if it’s a list of places that you won’t be able to go to as a result of climate change. They ran a sort of a Bucket List of iconic spots on earth that you absolutely must see before rising temperatures and sea levels change them forever. Dive spots like Key West, and the Great Barrier Reef and the Maldives; the Alps; Alaska, the Napa Valley and an ecological treasure like the Amazon, among others.

The superintendent of Yosemite National Park recently stepped down after a congressional hearing addressed allegations of sexual harassment. (Photo: sota, Flickr CC-BY-SA 2.0).

CURWOOD: Hmm, well I think they should have put “home” on the list because for a whole lot of people they’re not going to be able to go home again as climate disruption proceeds.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, you’re absolutely right about that. But here’s one thing that bothered me the most, and that’s that of all the places on the Conde Nast list – I haven’t been to any of them. So maybe it’s time to empty out the nearly empty bank account and leave my carbon footprint in all of these beautiful spots.

CURWOOD: Yeah, there’s that. But if you follow the magazine’s advice and burn up the miles to get to all of these places, you’re not exactly helping, are you?

DYKSTRA: Nope.

CURWOOD: Well, OK. What’s next?

DYKSTRA: Steve, a little update on a story you did back in April. We’re often tempted to think of workplace sexual harassment as something that might happen in a typical office, not in a National Park or a laboratory.

CURWOOD: Yeah, that’s right, we spoke with women who said they were victims of harassment in the National Park system.

DYKSTRA: This week, after a stormy Congressional hearing dealing with allegations of sexual harassment and intimidation, the Superintendent of Yosemite National Park stepped down. Don Neubacher is a 33-year veteran of the Park Service. It’s important to note that he is not facing any criminal charges, but a Park Service investigation cited a work environment at Yosemite that they described as “toxic, hostile, repressive, and harassing.”

CURWOOD: Hmmmm, not exactly what you’d expect to hear from a place that’s called a “cathedral of Nature”.

Prominent UC Berkeley astronomer Geoff Marcy (above) resigned last year after he was accused of sexual harassment. Three female astronomers who were harassed by Marcy are featured in a CNN report this week. (Photo: Raphael Perrino, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Yeah, and here’s one more: a CNN report last week featured three female astronomers who all say they were harassed on the job – in the observatory – by a superior. A prominent Cal Berkeley astronomer, Geoff Marcy, has often been called the most prolific planet-finder in astronomy. But he resigned last year after a sexual harassment investigation and allegations that he engaged in inappropriate behavior, including kissing and groping. The story was originally broken on the website BuzzFeed and, by the way, Marcy wrote a public apology, saying he didn’t intend to harm anyone.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Hey, what’s on the history calendar this week?

DYKSTRA: I’ve got a dubious 50th anniversary for you. On October 5, 1966, the Fermi nuclear power plant, located about 30 miles outside Detroit, suffered a partial meltdown. A piece of metal floating around in Fermi’s containment vessel set off a series of events that led to a near disaster. Officials say there was no radiation release, and the reactor’s liquid sodium coolant didn’t explode. That’s what it does if it comes into contact with air or water.

CURWOOD: But if it had, it would have triggered a catastrophe, I believe.

The first Enrico Fermi Atomic Power plant circa 1964 at Lagoona Beach, Michigan. The plant suffered a partial meltdown in 1966 because a piece of metal was floating in a containment vessel. (Photo: U.S. DOE, public domain)

DYKSTRA: Probably. And the Fermi incident is a milestone in the crisis of confidence that’s plagued the nuclear industry for half a century, and that’s in part because nobody ever found out about Fermi until years later. They were silent about it. The nuclear industry has years of steady operation. Then they get a Three Mile Island, then Chernobyl then Fukushima. Supporters, including quite a few environmentalists, tout nuclear as a partial fix to carbon emissions and climate change. But the public, and perhaps more importantly Wall Street, remain wary to this day.

CURWOOD: They do.

Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health news, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks Peter we’ll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories on our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Conde Nast Traveler

- Living on Earth’s story on sexual harassment in parks

- Yosemite National Park Superintendent Resigns

- CNN’s story on sexual harassment among astronomers

- Original BuzzFeed story on Marcy’s harassment

- Geoff Marcy’s resignation

- Fermi anniversary

[MUSIC: David Grisman/Denny Zeitlin, “Fourteen Miles To Barstow,” New River, David Grisman, Acoustic Disc]

CURWOOD: Coming up...why some scientists are saying trees have societies and can feel pain. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Time For Three, “Hallelujah,” Fervent Travelers, Leonard Cohen/arr.Time For Three, Time For Three and E1 Music]

BirdNote: When the Amazon Floods

A Scarlet Macaw. (Photo: Tom Conger)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC - BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: Hurricane Matthew has left massive floods and destruction in its wake. But, as Mary McCann explains in today's BirdNote®, for the vast Amazon rain-forest and its creatures, flooding is a different experience.

BIRDNOTE®/ WHEN THE AMAZON FLOODS

[Russet-backed Oropendola song http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/60723, 0.13-.18]

MCCANN: To us humans, flooding can often seem like an unmitigated catastrophe. In the right circumstances, though, when it’s predictable and wildlife is well adapted, flooding can create a biological bonanza.

In the Amazon River Basin, annual heavy rains can raise water levels 30 to 40 feet in just days. The basin is almost flat, sloping just one inch per mile over its eastward flow to the Atlantic, a journey of some 2,000 miles. So, when the rain arrives, forests flood, and a massive push of sediment erects new islands almost overnight.

It’s a lush world that scientists and nature travelers explore by boat, where some of the world’s most iconic birds find fruit in the trees or perch at the water’s edge.

[Chestnut-fronted Macaw call, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/68380, 0.06-.08]

Toucans and macaws, tiny pygmy kingfishers, tiger-herons, and massive ringed kingfishers.

A Russet-backed Oropendola. (Photo: Tom Grey)

[Ringed Kingfisher call, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/211555, 0.10-.12]

Oropendolas sing a startling refrain.

[Russet-backed Oropendola song http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/60723, 0.13-.18]

These birds are part of the richest array of life on earth, an extraordinary mosaic of habitats, all intricately linked. And all dependent on the river system that holds one-fifth of all the world’s fresh water.

I’m Mary McCann.

[Russet-backed Oropendola song http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/60723, 0.13-.18]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. 60723 and 68380 recorded by Paul A Schwartz. 211555 recorded by Gregory F Budney.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

© 2016 Tune In to Nature.org October 2016 Narrator: Mary McCann

http://birdnote.org/show/seasonal-flooding-amazon

CURWOOD: Swoop onover to our website, loe dot org, for some pictures.

Related links:

- Russet-backed Oropendola’s song

- Chestnut-fronted Macaw call

- Ringed Kingfisher call

[MUSIC: Time For Three, “Ecuador,” Fervent Travelers, Ranaan Meyer/arr.Time For Three, Time For Three and E1 Music]

The Hidden Life of Trees

A 4,000-year-old beech forest in Peter Wohlleben’s forest district in Hümmel. (Photo: Peter Wohlleben)

CURWOOD: According to Greek mythology, the trees in a certain grove could talk, with the gift of prophecy, and there are many other stories of talking trees, from the Disney film from Pocohontas to the Lord of the Rings. Well now a German forester says trees can talk, at least to each other. Peter Wohlleben also believes forests are social networks where individual trees not only communicate with each other and warn each other of impending dangers, they also care for their sick and elderly and live shorter lives if they can’t connect with each other. Peter Wohlleben’s book is called The Hidden Life of Trees, and he joins me now from Germany.

Welcome to Living on Earth Peter!

WOHLLEBEN: Hi. Hello.

CURWOOD: Now, where is your forest there in Germany?

WOHLLEBEN: My forest is in the western parts of Germany just a little distance to the Belgian border in the Eifel Mountains. We have beautiful forests there.

The old moss-covered stump, which Peter Wohlleben first thought was a stone (Photo: Peter Wohlleben)

CURWOOD: So, I want to warn our listeners to strap on their seat belts because we're going to go to some heights of thinking about trees that people usually don't go. We'll talk about trees maybe having brains, having societies, having some sort of a memory. Peter, you began your book with the chapter called “Friendships” that describes how you stumbled upon a rather remarkable set of mossy green, might I say, stones? What did those stones turn out to be?

WOHLLEBEN: They turned out to be a century-old stump. The tree I think was felled 500 or 400 years ago, and when I stumbled upon it and researched it, I found out that it was still living without any green leaf, and that seemed to be impossible because a tree is a living being which burns sugar in its cells, like we do. And after 400 years every molecule of sugar should have been gone, and the only explanation was that this old stump was supported by its neighbors.

CURWOOD: Supported by its neighbors? Why do some trees feed a nearby stump?

WOHLLEBEN: Yeah, that sounds incredible because we all learned in school that within evolution each being is struggling against each other so that just the fittest survive, but in the forest we have a social society which fights for each other so the whole forest will survive. Every tree is interested to keep its neighbors because together they create a special climate which is cool, which is humid, where every tree feels comfortable.

CURWOOD: By the way, what kind of tree was this stump?

Tree roots are believed to contain a great deal of a tree’s accumulated ‘knowledge’ (Photo: Tim Green, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

WOHLLEBEN: The stump is an old Beech tree. Beeches were common to all Germany, to all Central Europe into the eastern part of the United States and to some parts of Canada. Nowadays we have most of those areas changed into plantations of Spruce and Pine and so on.

CURWOOD: So, if this stump was some 400 years old, how old were the trees that were taking care of it?

WOHLLEBEN: We don't know because these trees weren't planted, so just can guess how they are. I think they are about 200 years old. We don't have any very old trees in Germany because each tree, when it gets a certain age, will be felled. So, the timber industry, that's a very sad chapter, and without very old forests we can't detect what's going on.

By necessity, the roots must be cut when the tree is planted; but this practice, among other factors, shortens the life of urban trees. (Photo: DeepRoot, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: In your book you imply that there must be some relationship between that stump and the trees that are feeding it. Maybe family?

WOHLLEBEN: Yeah, that's really possible. Susan Simard from the University of British Columbia found out that, for example, mother trees are able to detect their childs from other young trees, and that they are also have favorite childs which they feed more than other childs, which sounds incredible and perhaps even not so nice, but that's something which even trees have.

CURWOOD: What do you think the odds are that the trees around it were daughters or sons of this mother or father, that they were taking care of their parent?

WOHLLEBEN: That's possible because trees, they have in their root tips, brain-like structures. The University of Bonn found that brain-like processes are going on so that the trees can manage to find out, is it a neighbor, is it a different species, are that are my own roots or is a beloved child or grandfather or whatsoever?

CURWOOD: OK, wait a second. You're talking about brains in trees. How could a tree have a brain?

WOHLLEBEN: Yeah, that's really something special because it's not a brain like we have, and that makes it a little bit complicated to understand because we really don't know exactly where the brain of the tree is. We know that the root tips have brain-like structures, but that doesn't mean that the brain is there. We don't know where a tree stores its memories, for example. Some memories are stored in the branches. We know that, for example, in spring trees can count the days above 20-degrees Celsius because when it's getting warm in March that doesn't mean that the spring is really there.

A branch from a little beech tree. Each knot on the bark represents one year of growth and shows how slowly the young tree is growing. (Photo: Peter Wohlleben)

There may be some days after, for example, in April where deep frosts can destroy the new leaves, so the trees have to wait until the spring is really there, and therefore they count the days, the warm days and just when a certain amount is counted, then the new leaves appear, and that means that a tree do not just count but also has a memory. Trees can also remember, for example, heavy droughts. In the year 2003, we had in Germany a very heavy drought during the summertime, and trees which were not used to dry summers, they suffered very hard. The wood cracked, and that hurt them, and afterwards those trees changed their strategy of water consumption. They know that they don't have to use too much water in spring because they had to save some water for the next maybe dry summer. So, a tree can remember what has been going on in the past and after that change its strategies to a new way of water consumption, and that was something very surprising.

CURWOOD: So you're saying that trees are capable of learning, and you wrote that in your book. What do you mean?

Beech seedlings (Photo: Mark Robinson, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

WOHLLEBEN: Yeah, trees are also able to learn from other trees, for example, this case of this heavy drought. It concerns at first trees which are standing on dry earth. They are the first ones to suffer from a drought, and, when they recognize that the water is running out, then they give information to other trees through their roots and through a family network and those other trees learn that there is something going on with a drought or with an insect attack, and then they can prepare and reduce their water consumption, or, when an insect attack is going on, they may bring poison into their bark and they store this memory, and the next situation like this they may react much faster.

CURWOOD: How do trees communicate? How fast does that communication go?

WOHLLEBEN: Trees are very slow. For example, electrical signals in their tissue needs perhaps one or two second per inch. Therefore, they may react within minutes or hours or even days. Because this electrical signal will use maybe several minutes from the upper tree down to the roots, there's a second way to communicate with chemical signals which are sent out from the leaves, and the trees around may smell it, and therefore smell, “Ah, this is a special beetle which is attacking the neighbor tree.” And they may prepare much faster than being informed through the roots.

CURWOOD: So electrical impulses travel through the trees very slowly, but rather the way nerves transmit things, and they can warn each other of danger. Peter, why is it useful for forest managers to understand trees as social beings?

WOHLLEBEN: Because healthier forests will also produce more timber. But for me the main thing is foresters should be treekeepers, and the first aim should be to keep a healthy forest for the next generations. The forest is much more than timber, for example, this old Beech forest which I'm responsible for contains more than 10,000 animal species, and when you clear-cut it and replace it, for example, with a Douglas Fir or a Spruce, then most of those species will be run out and replaced by species which are not common to our region.

Even selective logging (as opposed to clear cutting) harms forests, according to Wohlleben. (Photo: barnimages.com, Flickr public domain)

CURWOOD: Peter, what is lost when old growth is cut? How does that change the behavior in the social network of trees?

WOHLLEBEN: Even when you make a thinning and just cutting one of the other trees and leave, for example, 50-percent of the trees untouched, this social network is destroyed. When you do it like this, you makes a tree changing from a social being to single. Those trees suffer. They don't get very old. For example, a Beech may grow as old as 400 years and when you make a thinning in such a forest, this Beech will die at around 200 years, nearly half the age which is natural.

CURWOOD: Peter, how are urban trees very different from the trees that have grown up in a forest?

WOHLLEBEN: Urban trees are a special thing. Urban trees are like street kids without parents. They can grow as they want to grow, and in a metro forest, in a primeval forest, those old mother trees didn’t rely down to like 3-percent, so the little ones may produce just as much sugar that they don't die, but not more. They are not allowed to grow in the first 200 or 300 years. In the street, they get from the first day on light as much as they want.

They can grow, they can produce sugar as much as they want and they grow in a very unhealthy way, very, very fast. That's what we want to have in our streets. We want to have in a short time big trees because they look so nice, but those trees can’t become very old. They will die earlier. There is another problem. When you let the street light burn the whole night, then trees can't sleep, and they will die earlier that trees which may sleep at night without any light.

CURWOOD: So, in Boston where we have our studios, up and down the streets there are not a lot of very old trees even through the streets are very old. What would've happened to those trees to prevent them from getting to be old? After all, they're protected in the city. No one is likely to cut them down, unless there's a storm or something.

A 200-year-old mother beech tree with its 150-year-old child (Photo: Peter Wohlleben)

WOHLLEBEN: Yeah, but they are without their social network. Those trees are all singles. They are all on their own like Robinson Crusoe on an island. We think we have, for example, in the street a row of trees which should be connected but in reality the distances are too far. The roots are destroyed. The root tips, they have been cut, because otherwise the roots were too big to plant. And with those cutted roots, the trees are not able to connect anymore.

CURWOOD: When did you realize that individual trees can communicate with each other, care for their sick, warn each other of impending dangers?

WOHLLEBEN: I think, the first time, I knew about trees as much as a butcher about animal feelings. But afterwards, to rescue the old Beech forest, we made part of them into a burial ground. People may buy an old Beech tree instead of a gravestone and be buried in form of an urn, and together with those people I learned to look new at trees. As a forester, you see a tree and every tree planks or you see paper or whatsoever. Then, when I began to look more and more, I discovered more which makes it nowadays a little heavy to cut any trees which I have to do.

CURWOOD: I imagine. Peter, how are people reacting to your research?

WOHLLEBEN: Most people are reacting friendly because I just write things which they always thought might be true, but really, bad critics are coming from foresters, and think, I believe it's because I disturb their jobs, their profits, because when people register the trees have feelings then we can't treat them like we do nowadays, with cheap methods, for example, by harvesting those trees with big machines, destroying with those heavy machines the storage possibilities of the soil by compressing the soil and so that no water may be stored from the winter. So it's true that most bad critics are coming from colleagues from me, and applause is coming from, let's say, normal people which always thought there has to be more than just timber from trees.

CURWOOD: Overall, how well are we doing managing the forests on our planet here on Earth?

Peter Wohlleben is the author of Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate – Discoveries from a Secret World (Photo: Tobias Wohlleben)

WOHLLEBEN: I think we are treating them very bad in the moment. For example, those clear-cuts are not just destroying those social systems, but also the factories for wood. When you cut a forest complete down, you have nothing to produce timber. We have changed here in this little village where I'm living, the forest methods, and afterwards we have created more jobs, we have earned much more money, and the forest is healthier. So, we have ways to use timber without disturbing the forest too much. Trees which can get very old store carbon at the same time, that's clear. But in the moment, all I see is the fast profits. There's no thoughts about the future and the next generations.

CURWOOD: Peter Wohlleben is a forester and author who cares for an environmentally friendly woodland for the village of Hummel in Germany. His new book is called "The Hidden Life of Trees". Thank you so much.

WOHLLEBEN: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- Peter Wohlleben’s website

- About Peter Wohlleben’s work as a forester in Hümmel, Germany

- The Hidden Life of Trees book

- The Ancient Beech Forests of Germany comprise a UNESCO World Natural Heritage site

[MUSIC: David Grisman/Denny Zeitlin, “Brazilian Street Dance,” New River, David Grisman, Acoustic Disc]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Aidan Connelly Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Emmett Fitzgerald, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Alex Metzger, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt.

Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood.

Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth