October 28, 2016

Air Date: October 28, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Carbon Tax Up for Vote in Wash. State

View the page for this story

Washington State’s Initiative 732 would enact America’s tax on carbon, if voters agree. Proceeds would go to reduce sales taxes and support local industry, but some environmental justice activists say it would do too little to help the poor or benefit renewable power. Vox writer David Roberts discusses what’s at stake with Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood. (09:10)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra finds a ballot initiative in Florida that affirms homeowners’ right to solar power is actually designed to discourage rooftop panels. He also discusses with host Steve Curwood fake twitter accounts that enthusiastically support the Dakota Access Pipeline, the focus of bitter protests. And in this week’s trip into history, the two mark the anniversary of a major flood in Florence that destroyed some iconic pieces of Renaissance art. (04:30)

Wildlife Trafficking on Oregon Ballot

/ Jes BurnsView the page for this story

Oregon voter will decide Measure 100, which would ban the buying and selling of various illegal animal products. As EarthFix reporter Jes Burns explains, the twelve species the measure would cover are at risk of extinction and poached internationally at high rates. But opponents of the measure say the lack of funding means it promises more than it could deliver. (05:20)

Climate and Ozone-Friendly Coolants

View the page for this story

In 1987, nations agreed to phase out stratospheric ozone-harming chemicals called CFCs under the Montreal Protocol. But the replacement compounds HFCs turned out to be powerful greenhouse gases, so now countries have agreed to phase these chemicals out under the same international agreement as well. Nobel prize recipient Dr. Mario Molina discusses with host Steve Curwood the risks HFCs pose to the climate and the international decision to stop using them. (06:55)

Svalbard Coal

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Norway’s Svalbard Archipelago is home to the northernmost coalmines on earth that have powered the tiny community and earned export cash for a century. Resident Explorer Mark Seth Lender visited Svalbard, and was struck by its many contrasts. (02:40)

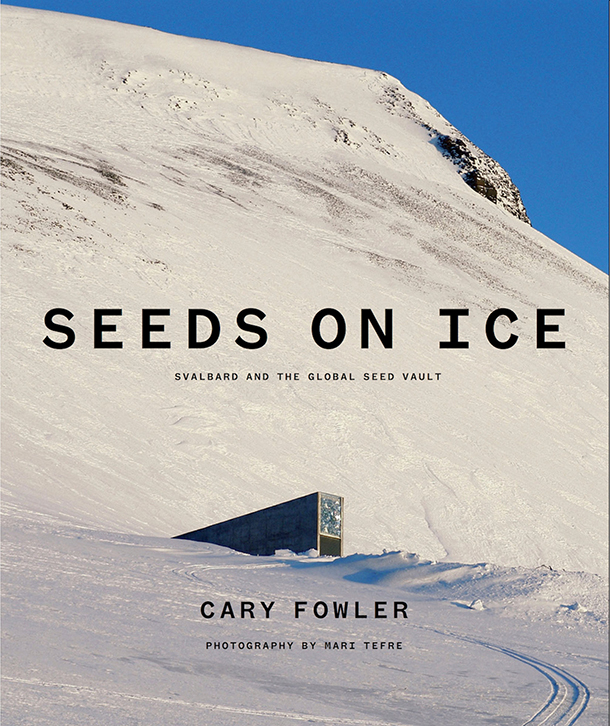

Seeds on Ice: Preserving the World’s Agricultural Heritage

View the page for this story

Deep in an icy mountain not far from the North Pole are rows upon rows of boxes filled with seeds -- nearly a million samples gathered from nations collections around the globe. Cary Fowler is a founder of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault and the author of the new book documenting its story and its treasures called Seeds on Ice. He joins Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer to explain why humanity needs a seed vault at the top of the world to ensure the genetic diversity of our agricultural heritage. (18:55)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: David Roberts, Mario Molina, Cary Fowler

REPORTERS: Jes Burns, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Washington State could pass America’s first in-the-nation tax on carbon, but some economic and environmental advocates oppose it.

ROBERTS: What these communities are trying to convey to people is the climate movement has got to become a climate justice movement if it wants to succeed. It cannot just focus on carbon, it's got to focus on justice and fairness.

CURWOOD: Also, how an Oregon ballot initiative would cut down on trading in products from endangered animals, but also destroy the value of some carved ivory.

BECKSTEAD: What is more important? Is it more important for that person to gain a nominal profit from the sale of that item, or is it more important to make sure that these wild animals are available for generations to come?

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Carbon Tax Up for Vote in Wash. State

Proponents of the CarbonWa ballot initiative say it’s the most progressive shift in the state’s tax code in 40 years. (Photo: Carbon Washington)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. There are some 160 or so ballot initiatives this year across America, with measures to raise the minimum wage, legalize marijuana, and control guns gaining much of the attention. And in Washington state, action on climate change is also on the November 8th ballot in the form of Initiative 732, which would tax carbon emissions. Many folks on the left and right in Washington agree on the need to put a price on carbon, but they can’t agree on how to do it, and they are pulling against each other when it comes to this initiative, though if it passed it would impose America’s first carbon tax. David Roberts writes for Vox online and recently wrote about the tangled political factionalism surrounding the carbon tax referendum. David, welcome to Living on Earth.

ROBERTS: Thanks for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: Give me the background. What's the story here?

ROBERTS: Well, the short version is an economist PhD by the name of Yoram Bauman founded a group called Carbon Washington, wanted to push a revenue neutral tax swap as they call it and started gathering friends and funders and signatures to get on the ballot, and as of January of this year submitted those signatures, and so the ballot measure will be on the ballot about this year.

CURWOOD: So I gather many folks will see that as a reasonable approach, but apparently not everyone does.

ROBERTS: Yeah, that's right. The other part of the backstory is that there's this other group of environmentalists who have been working to build a coalition in Washington State of various liberal groups including labor, communities of color, low-income groups. That group was intending to put a ballot measure on the ballot this year. Consequently those groups on the left are not supporting it, so what you have is the odd situation of a carbon tax on the ballot that is being opposed by the state Democratic Party, by community of color groups, low-income groups and by most environmental groups.

Washington state has a history of leading the environmental charge -- in 1975 architect Richard Haag transformed the site of a defunct gasification plant in Seattle into one of the country’s first post-industrial public spaces, known today as Gas Works Park. (Photo: Michael D Martin, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Interesting situation. Please explain for us what you mean by revenue neutral?

ROBERTS: Sure. All the revenue that is gathered by the carbon tax will be automatically returned. By far the biggest chunk is going to reduce the sales tax. So, that's what “tax swap” means. You raise one tax, lower another tax and the government doesn't get any discretionary revenue to spend. So that's why they call it revenue neutral. It doesn't raise revenue for the government.

CURWOOD: Now, you've written that the solution imposed by this plan has a heavy climate-economist bent to it. What do you mean by that?

ROBERTS: Well, economists have always maintained that a price on carbon is the most economically cost-effective way of reducing carbon emissions and so then the big question becomes what do you do with all the revenue, and economists favor reducing other taxes with that revenue. You raise one tax, lower another tax, you don't raise the net tax burden, but now you're taxing things you don't want, carbon, instead of things you do want. So, that's the idea and economists have been advocating for this for years and years and years. This is the first example that I'm aware of where sort of the clean perfect economist-friendly version of this is actually on a ballot somewhere.

CURWOOD: What are the other proposals that the Alliance has put forward?

ROBERTS: Well, the Alliance has been developing its own ballot measure the most striking thing about it is it would also be a carbon tax. They don't disagree with the tax element of this. It would also be a fee on carbon, but theirs would be revenue positive i.e. all that revenue would go to the government that it could then have discretionary power over. So what do they want to do with the revenue? First they want to spend it on social justice which means the Working Families tax credit, it means worker transition programs, worker retraining. When that's taken care of then they divide the remaining money into 70 percent goes to clean energy and 20 percent would go to clean water and two percent would go to healthy forests. But in terms of the big picture, I think the difference here is that the Alliance program would be a massive government-spending program. There's no two ways about it. It would be a massive government-spending program funded by a carbon tax. That's the whole core of the difference. Carbon Washington thinks the price on carbon will be sufficient. So they think that their solution, that this revenue neutral carbon tax does serve social justice. So the big dispute here, the big policy dispute is A: what's the best way to serve social justice and B: who decides?

Despite heated debate within environmental policy circles, Washington State voters are largely unfamiliar with the initiative. (Photo: John Russell, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So these folks on the left say there is not enough economic or social justice in this measure are opposing it. What does that mean for the prospects for Washington to become the first state to have a carbon tax?

ROBERTS: Well, the betting money, still, I think among political professionals is that it's going to lose. Its yes numbers have crept up a little bit, but it's still got a large number of undecideds and that's still a grim scenario. The big question, of course, is could they have persuaded more of those undecided voters if the big left groups had swung around behind this measure and spent a bunch of money on it and spent a bunch money to get the word out. So if you ask the Alliance, they'll say this measure was doomed from the start, nobody could've saved it. If you ask Carbon Washington, they'll say, it's a tight race and we could've won this if these left groups had supported it.

CURWOOD: David, how does this proposal, how does this referendum question compare to other carbon taxes that are out there. I'm thinking particularly of British Columbia which already has one.

ROBERTS: Sure. British Columbia is sort of the inspiration or the model, but this carbon tax as proposed is far stronger than any tax in North America and would be one of the strongest, most powerful in the world. So, for instance, British Columbia's was set to rise up to $30 and then plateau there, and then stay there. This carbon tax is set to keep going and going until it reaches $100 a ton. That will probably be mid-century sometime, but it in terms of just the sheer level of the carbon price, it would get up to one of the highest carbon prices in the world. To find a carbon price higher than $100 dollars a ton you would have to look to Sweden.

CURWOOD: How will the debate over this initiative inform other states who are thinking about carbon tax plans of their own?

ROBERTS: One of the premises of Carbon Washington is that they wanted to put forward a policy that other states could adopt and their sort of political rationale is if we do what the alliance is trying to do which is just gather all the left groups together, that might work in California, maybe in Washington, maybe in Oregon but in most states, the left just isn't strong enough to pass policy on its own, the left just can't do it on its own. So if we're going to make a model for other states, it has to be a model premised on bipartisanship. So my worry is that this carbon tax going down to defeat is going to send a strong signal that's going to accelerate what is already extreme polarization on this issue.

CURWOOD: To what extent is this dispute creating a backlash against the left enviro-groups? Those groups are often criticized as using the environment as a Trojan horse for income redistribution and other social things.

David Roberts is a writer for Vox. (Photo: David Roberts)

ROBERTS: Traditionally the environmental movement in the US has been dominated by mostly white people, but even more than that, mostly affluent well educated people, and I think people like that tend to dismiss the needs that these communities have as sort of that they're just grubbing for handouts or something, that this is all kind of a sideshow, that all that really matters is carbon, carbon molecules, reduce carbon, that's the only thing that really matters, and I think what these communities are trying to convey to people is the climate movement has got to become a climate justice movement if it wants to succeed. It cannot just focus on carbon, it's got to focus on justice and fairness. Is it just about reducing carbon molecules or is the climate movement giving these groups a place at the table? And this is of course something that is inevitably going to bedevil national climate action as well. The same fight that’s going on here is going to be replicated I think almost everywhere you see climate policy being developed.

CURWOOD: David Roberts is a writer at Vox.com. Thanks so much for taking the time with me, David.

ROBERTS: Thanks a lot.

Related links:

- David Roberts’ reporting for Vox on the proposed Washington carbon tax

- Carbon Washington website

- CarbonWa: “Carbon taxes are even better than you think, Part III: Social Justice”

- The Alliance for Clean Jobs and Energy

- The Alliance’s alternative proposals

Beyond The Headlines

The Green Tea Party, a collaborative group made up of Tea Party members and environmental activists, is working to make rooftop solar power affordable and accessible for Florida residents. (Photo: Alex Lang, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, while he’s been digging beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra of DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, EHN.org, has found that Initiative 732 isn’t the only curious ballot measure out there. Peter’s on the line now Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter, what have you found?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve, you know there’s an unusual political effort that’s made some waves here in the southeast U.S. They call themselves the Green Tea Party, and it’s just what it sounds like, green groups playing nice with some in the Tea Party, uniting on clean energy even if they may not agree on things like who the next President should be.

CURWOOD: Political cooperation. What a concept!

DYKSTRA: Yeah and the two sides have united in opposing a Florida ballot measure that would enshrine the right to go solar in the Florida constitution.

CURWOOD: Wait, they’re united against the right to go solar?

DYKSTRA: No, they’re fine with that, but the language of Amendment One on the Florida ballot would also make it pretty much impossible for homeowners to afford the rooftop solar they’ve won the rights to.

CURWOOD: OK. Deep breath Peter, what’s going on here in the sunshine state?

DYKSTRA: Well, beyond the high-and-mighty language about Solar Rights, Amendment One would also give electric utilities the right to refuse to buy back solar power generated from individual homeowner’s solar panels, and that could be enough to chase the blossoming rooftop solar industry straight out of the state. Which may be why the $21 million that’s come in to finance Amendment One, much of it from four Florida electric utilities – is ten times what opponents have spent. And a leaked audio recording from Amendment One supporters seems to suggest that the ballot question and constitutional amendment are intentionally misleading.

CURWOOD: Hmm, sounds like the moral of this story is that, whatever the issue, read the fine print.

DYKSTRA: Yup, the educated voter thing.

CURWOOD: Hey what’s next?

DYKSTRA: More possible deception, not on the ballot but on Twitter, where at least character assassination is limited to 140 characters. For the second time in a month, a fossil fuel promotion group has been caught apparently creating fake Twitter accounts to make it appear they have broad public support.

CURWOOD: So you’re saying that everything people are saying on Twitter isn’t necessarily true? I’m shocked, shocked!

DYKSTRA: Well, not really, I’m saying that everything people say on Twitter doesn’t necessarily come from actual people. The clash between coal mining and renewable energy is a huge issue in Australia, and when the lights went out due to a storm in the state of South Australia recently, a Twitterstorm raged, blaming renewable energy for being unable to stop the blackout. A sleuth for Buzzfeed’s Australia news site tracked down the Tweeters, and virtually all of them were Twitter accounts less than 24 hours old, using profile photos taken from stock image files.

CURWOOD: Aha, so those Twitter attacks came from people who were literally born yesterday.

The news site DeSmogBlog recently uncovered that a front group was creating fake Twitter accounts to support the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL). (Photo: Darren Barefoot, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Right, and this closely echoes what seems to have happened last month in North Dakota. The news site DeSmogBlog tracked down 16 newly-established Twitter accounts that were very, very enthusiastic about the controversial Dakota Access Pipeline, how safe it would be, and how many jobs it would create, and these Tweets were critical of the anti-pipeline protesters that made headlines last month and you reported on recently. When DeSmog and others started asking questions online, those Twitter accounts vanished.

CURWOOD: Hard to believe anything’s real these days. Let’s turn to the history file where something actually happened at least, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: The fiftieth anniversary this coming week for disaster in one of Europe’s iconic Renaissance cities. After a week of steady rain, Italy’s Arno River overtopped its banks and levees and water poured through the streets of Florence. Seventeen people died, and the water and mud rolled through centuries old homes, churches and museums, damaging or destroying religious icons, sculptures and Renaissance artwork.

CURWOOD: Yeah, it was a disaster that touched lives and property, but also culture and history.

DYKSTRA: And a major disaster like that is something that Florence endures about once a century, with a lot of little floods in between. On the same calendar day in the year 1333, another huge flood killed an estimated 3,000 in the city and destroyed a landmark bridge, the Ponte Vecchio. Emergency planners say Florence is better prepared than ever for the next flood, but they also worry that the loss of upstream farmland to development may make the next flood worse.

CURWOOD: And that’s a common problem in a lot of places. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks, Peter. We’ll talk to you again real soon.

The flood of the river Arno in Florence on November 4, 1966 destroyed a number of art pieces and killed at least 17 people. (Photo: Ricce, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

DYKSTRA: OK, Steve thanks, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories on our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News: Florida solar ballot measure

- BuzzFeed: “Fake Twitter Army That Trolls Renewable Energy Linked To Mining Lobby”

- Common Dreams: Dakota Access Pipeline fake Twitters

- The Independent: The 1966 flood in Florence, Italy

- See pictures of the Florence flood

[MUSIC: Complesso A Plettro Di Taormina, “The Godfather Medley,” from Mandolini di Sicilia, Giovanni “Nino” Rota, Discoteca]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

CURWOOD: Coming up ... a quiet victory over a monster threat to climate stability. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Beppa Gambetta/Rushad Eggleston, “La citta vecchia/Iride,” Fabrizio De Andre/Pasquale Taraffo, live at the Beppe Gambetta Acoustic Night 14 (Teatro della Corte, Genova, Italy)]

Wildlife Trafficking on Oregon Ballot

Engravings on scrimshaw from the Maritime Museum of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC. (Photo: A.Davey, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Oregon voters this November will decide whether to ban the buying and selling of animal products like ivory, and jaguar skins. The 12 species covered under ballot measure 100 are being poached internationally at high rates and many are threatened with extinction. Supporters say Oregonians could do their part in the fight against animal trafficking with a “yes” vote, and if the measure passes, Oregon will join its neighbors, California and Washington, in having such a state law. But there are some questions about just how effective the Oregon Measure would be. Jes Burns of Oregon Public Broadcasting and EarthFix has the story.

BURNS: Back in the 1970s, Gens Johnson got really interested in hand-made and regional art. She started to buy pieces from shops in Portland and across the Northwest.

JOHNSON: I bought two pieces that were scrimshaw, and they were done on whale ivory and walrus tusk.

BURNS: Scrimshaw is a kind of carving – typically of boats and sea life. It was popularized by whalers in the 1800s. Johnson estimates hers were made in the 1960s or 70s.

JOHNSON: I was concerned when I bought it that it wasn’t elephant ivory, and I really didn’t think there was any problem with it being a sea mammal product.

BURNS: She gave the two pieces to her parents as a gift, considering the art a long-term investment.

JOHNSON: Someday I will inherit those, and I really don’t have … pinned any great gain on selling them, but I’ve always felt that would be one of my options.

BURNS: Under Measure 100, that option would go away. Her whale scrimshaw would be subject to a ban on buying and selling because it was made less than 100 years ago. Johnson is actually okay with that. But this dilemma gets to the measure’s larger question.

BECKSTEAD: What is more important? Is it more important for that person to gain a nominal profit from the sale of that item, or is it more important to make sure that these wild animals are here for generations to come?

A young Pangolin, one of the animals protected under Measure 100 (Photo: Valerius Tygart (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

BURNS: Scott Beckstead is Oregon Director of the Human Society of the United States, the main financial backer of the campaign. He says there are exceptions, many of which follow federal law that is already in place. For example, vintage musical instruments, like ivory-keyed pianos, and older antiques with established provenance. The animal trafficking measure would also allow items to be passed down through inheritance. The goal, says Beckstead, is to take away the economic incentive.

BECKSTEAD: Once the smugglers get items into Oregon, there is no state law to prevent those items from being bought and sold.

BURNS: Right now, federal agents are the only ones looking for trade in animals like tigers, whales and rhinos here. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Special Agent Sheila O’Connor is one of only four agents assigned to the entire state. She says wildlife trafficking is alive and well in Oregon and more officers would help.

O’CONNOR: We can’t be everywhere, we can go into every store, we can’t view every online page offering things for sale here in the state of Oregon. So if a state makes trafficking illegal, then we have a lot more eyes in the marketplace.

BURNS: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service does not have an official position on Measure 100. A recent report by the wildlife trade monitoring organization TRAFFIC shows ivory availability dropping in states that have banned sales. The study examined six U.S cities and among them, Portland, Oregon was flagged as having the second highest amount of ivory on the market. If the wildlife trafficking measure passes, that stands to change. Oregon would join Washington and California in having similar bans, says Beckstead.

BECKSTEAD: If we can get Measure 100 passed, then the entire west coast of the U.S. suddenly becomes far less hospitable to the smugglers.

BURNS: But how effective that united front will be really depends. Washington’s voter-approved ban passed by a landslide, and has been in effect less than a year. Deputy Chief Mike Cenci of the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife says his officers have added the banned animals to their watch list.

CENCI: But as far as putting together an operation and starting to focus attention on a known trafficker, we’re a long ways from doing that in effective way that address species beyond our local critters.

A room filled with various confiscated wildlife products at JFK Airport (Photo: Steve Hillebrand, [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

BURNS: A big reason? Washington’s measure didn’t include additional funding to enforce the ban. Oregon’s doesn’t either. Officers would be relying on the same staffing and budgets they use to enforce the rest of the state’s wildlife laws. Given this, it’s unclear whether Gens Johnson and her whale ivory scrimshaw would ever come under scrutiny.

JOHNSON: It feels to me like overkill – no pun intended – in terms of making it a law without the ability to increase enforcement.

BURNS: There hasn’t been any formal opposition to Oregon’s wildlife trafficking measure. And even Johnson, whose family art collection stands to lose value, says she supports the intent of the measure to conserve these iconic animals. For Living on Earth, I'm Jes Burns.

CURWOOD: Jes Burns reports for EarthFix and Oregon Public Broadcasting.

Related links:

- More information on Measure 100

- Website for Yes on 100, a pro-measure advocacy group

- Dr. Mark Trexler of the Climatographers, on the complications of Measure 100

[MUSIC: Natraj, “Dobro Dosle,” from The Goat Also Gallops, Bulgarian traditional, Dorian Discovery Recordings]

Climate and Ozone-Friendly Coolants

Negotiators at the 28th Meeting of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol in Kigali, Rwanda celebrate the adoption of the Kigali Amendment, a plan to phase out the use of climate-disrupting hydrofluorocarbons. (Photo: Rwanda Environment Management Authority, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: The Montreal Protocol has been hailed as one of the most successful international treaties in history. It was forged in the late 1980s to phase out CFCs, or chlorofluorocarbons, chemicals used in refrigeration that destroy the ozone layer that shields Earth from cancer-causing ultraviolet radiation. But ozone-harming CFCs were replaced with hydrofluorocarbons, or HFCs, that don’t harm ozone, but are potent greenhouse gases, up to a thousand times stronger than carbon dioxide. So this October, negotiators agreed to replace HFCs with chemicals that are both ozone and climate-friendly. One of the first scientists to discover the dangers of CFCs for the ozone layer was Mario Molina, who shared the 1995 Nobel Prize for chemistry for his work. Mario Molina now teaches at the University of California, at San Diego, and joins me. Welcome to Living on Earth.

The stratospheric layer ozone hole over the South Pole in September 2009 (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MOLINA: Thank you, I’m glad to be in your program.

CURWOOD: So, what exactly have the world's nations agreed to do the curb HFC use?

MOLINA: What the nations have agreed to do is not to manufacture industrially this chemical, which does not occur naturally. It has been manufactured to replace the CFCs, chlorofluorocarbons that do affect the ozone layer and the Montreal Protocol -- the agreement was to ban the production of those chemicals for the sake of protecting the ozone layer. What the Kigali Agreement does it no longer deals with the ozone layer but now with climate change because the HFCs, they have this problem of affecting instead the climate.

CURWOOD: Now, there three different tracks for nations under this agreement. How does that work and how fair do you think is this differentiated burden?

MOLINA: I think it works. It's the way to get all the nations to agree to this Agreement and the reason perhaps is best explained by using India as the example because they claim they cannot replace the HFCs that they are using now very soon because they would not allow their many families or poor families to have air conditioning because the replacement is a bit more expensive and because the new compounds are not yet available. With the original Montreal Protocol, there were some funds called the multilateral funds that were already useful helping developing nations enforce the Montreal Protocol and ban CFCs, they just had a longer time to be able to do that, and they have resources from developed countries. So the same thing has happened with the Kigali agreement, again, now for climate change rather than for the ozone layer.

CURWOOD: Tell me, how much do HFCs presently warm the atmosphere and how much warming will be avoided because of this phase-out under this agreement?

MOLINA: At the moment they do not contribute very much because the main contributor is carbon dioxide and methane and other compounds. But the big worry is that as the world develops, you are talking about India versus China, and many other developing countries, as they become more wealthy, they will use more and more air conditioning, and without the Kigali Agreement, they would use HFCs, and so the expectations, looking at projections how much HFCs will be produced. You would avoid something like half of the increase in the temperature by mid-century because of this new agreement.

Developing climate-friendly cooling alternatives to HFCs is especially important as more and more people in India and elsewhere become able to afford air conditioning. (Photo: Wolf Gebhardt / Deutsche Welle, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So that's a half a degree Celsius we're talking about.

MOLINA: Yes, yes.

CURWOOD: So in round numbers that's almost a full degree Fahrenheit difference.

MOLINA: That's correct, yes.

CURWOOD: Now to what extent have businesses been involved in the HFC phase-out effort?

MOLINA: Well, the chemical industries, as was the case with the CFCs, at the very beginning they are supposed any action because they thought the science was not established, but this is just history now. The science became very well-established and the industry, then the chemical industry they agreed to collaborate, and agreed with the Montreal Protocol phasing out CFCs and they designed other compounds. So it's the same companies and a few more that are now investigating and exploring another set of compounds that you can use for air conditioning but are not global warming agents.

CURWOOD: How easy is it to replace hydrofluorocarbons with other chemicals in cooling systems?

MOLINA: Well, the HFCs can indeed be replaced in the same manner that the CFCs were replaced. The industry investigated and developed replacements, so the expectation is that industry will come up with cheaper alternatives, but even at the present time I insist there are many air conditioners that function very well with other refrigerants and you need perhaps better designed air conditioners. The air conditioners themselves consume quite a bit of energy if they have not very well manufactured. So that's another part of the story.

In 1974 chemist Frank Sherwood Rowland (left) and his post-doctoral student, Mario J. Molina, suggested that chlorofluorocarbon molecules would be broken down by ultraviolet radiation in the upper atmosphere, release chlorine atoms, and thereby cause the breakdown of ozone. (Photo: UCI UC Irvine, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: What are those other refrigerants that work at this point?

MOLINA: There's a range of chemicals that can be used as refrigerants. First of all, there are different types of HFCs and organic compounds containing carbon, halogens like Fluorine and Hydrogen. It's just that they have different formulas, but you can also use different types of refrigeration, even Carbon Dioxide itself is something that can be used for example in automobile air conditioning.

CURWOOD: By the way I want to ask you, when did scientists recognize that the hydrofluorocarbons which replaced the ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons we're damaging in their own way namely adding to the greenhouse effect?

Prof. Mario Molina teaches at the University of California, San Diego (Photo: Centro Mario Molina)

MOLINA: Well, it was actually Professor Ramanathan at the University of California, San Diego who first pointed out that the CFCs themselves are greenhouse gases. That's why the Montreal Protocol, because they banned CFCs, did more for climate change than the Kyoto Protocol or even the beginning of the Paris Agreement. So, it was not surprising that the HFCs are also climate agents. You have to not just measure how strongly they absorb infrared radiation but you also have to deal with their lifetime. How long will they remain in the atmosphere?

CURWOOD: How long do they last?

MOLINA: Well, there are several different ones, but they last of the order of 10, 15, 20 years, comparable to methane, the longer lived ones. But CO2 lasts, some of it, after it's been emitted, is absorbed by the oceans, but maybe one-third of it remains for a millennium, so carbon dioxide is very much longer lived.

CURWOOD: UC San Diego Professor Mario Molina is a recipient of the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Thank you so much, Professor Molina.

MOLINA: Thank you. I'm really glad to be on your program.

Related links:

- European Commission on Climate-friendly alternatives to HFCs and HCFCs

- About Dr. Mario Molina’s organization, Centro Mario Molina

- Scientific American: “World Leaders Agree to Phase Out Heat-Trapping Hydrofluorocarbons”

- United Nations Environment Programme report, “HFCs: A Critical Link in Protecting Climate and the Ozone Layer”

- NASA: What the ozone layer would look like if CFCs hadn’t been banned

- NASA: Even HFCs deplete stratospheric ozone

[MUSIC: Gavriel Lipkind, cello/Alexandra Lubchansky, piano, “Chonguri,” from Miniatures & Folklore, Sulkhan Tsintsadze/arr. Lipkind, Lipkind Productions]

Svalbard Coal

The Zapolyarye, a Russian coal carrier, taking on a load of Svalbard coal (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Off to the top of the world now, to a small group of islands halfway between Norway and the North Pole. The Svalbard Archipelago is home to the Global Seed Vault, twice as many polar bears as people, and the northernmost coal mines on earth. Resident Explorer Mark Seth Lender paid a visit, and was struck by its many contrasts.

A miner’s graveyard, Svalbard (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

LENDER: Above the Arctic Circle lies a valley that a glacier made. There, a river fed by the fast-melting ice rushes toward the dark fjord and into the Greenland Sea. Straddling the river is the company town of Longyearbyen. Svalbard Kirke with its unadorned Lutheran lines on the one bank; the working folk of the town and their dwellings and small commerce on the other.

High, on both sides, scarring the cliffs, are the remnant of the mines.

Fire has stained the mouth of every pit, the stones rust-colored from the flames; No one alive remembers the burning. Gone the men who dug the coal, who heard the wires sing as the coal cars rolled in the cableway down to the docks, who were there -- for the cave-ins, and the gas, and the orange roar of the flames. Who remember the long work lying on their sides in a three-foot seam, the rockdrill clamoring…

All is silence now, except for the endless ringing in the ears.

A polar bear on the Svalbard archipelago (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Two million tons of coal! Under the sun when it never sets and in the long months when the sky is dark as the anthracite wrenched from frozen ground. Year in. Year out. And in the aftermath, every glacier in retreat. From here until the land ends at 81 North Latitude the ice is scored with dark lines (the tally-marks of profit and of enterprise).

Just up the hill from the giant loading crane the Seed Vault tunnels through the permafrost and into the ancient granite shield. Just down the road the funnel of the power plant pours out black smoke across the hard-packed snow. And at the docks, where the cableway comes to an end, a Russian ship is taking on the last of the mounded coal. Pure white upon her sky-blue stacks the painted image of a polar bear.

An abandoned Svalbard coal mine (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: For some of Mark’s photos of the mines and cable cars and polar bears head on over to our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- The archaeological history of Svalbard

- The Barent Observer: Article on the future of a coal-free Svalbard

- Mark Seth Lender's website

- Additional glimpses of the abandoned mine community in Svalbard

[MUSIC: Thomas Roth, “Ingredients,” from Thomas Roth Nyckelharpa Ingredients Vol. 1, self-published YOUTUBE: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7sfBcWvVUbs]

CURWOOD: Coming up ... seed saving on a super scale. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies -- combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward.

This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Eileen Ivers & Immigrant Soul, “Zululand (Reprise),” from Eileen Ivers and Immigrant Soul, Irish traditional/arr. Ivers, Kumalo, Koch Records]

Seeds on Ice: Preserving the World’s Agricultural Heritage

Cary Fowler led the effort to create the Svalbard Global Seed Vault (Photo: Mari Tefre)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Time now to dive into a breathtaking and beautiful new book that chronicles a profound and visionary investment of hope. It’s called Seeds on Ice, and there are not many words but plenty of pictures that explain the thinking and work that created the Global Seed Vault at Svalbard. Author Cary Fowler spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

PALMER: Cary Fowler, you are the father of the Global Seed Vault. First of all, tell me what exactly this global seed vault is.

FOWLER: The Global Seed Vault -- the Svalbard Global Seed Vault -- is a backup insurance policy for all the seed banks around the world, and the idea is that we want to provide failsafe protection for the diversity of our agricultural crops, diversity that is stored in the form of seeds. You need cold temperatures, freezing temperatures, to conserve seeds long term. So we went close to the North Pole where it's very cold, and we built a facility inside of a mountain, which makes it also very secure, and there we're storing backup copies, seed samples of currently more than 850,000 different crop varieties.

PALMER: They are already national collections, as you've said, and seed vaults. Why do we need a backup?

The photographs in Seeds on Ice: Svalbard and the Global Seed Vault are by Mari Tefre. (Photo: Mari Tefre)

FOWLER: We need a backup because bad things happen to seed banks, and there's so many examples of this that are catastrophic at a local or national level. There's been a fire and a flood inside the Philippine national gene bank, the Iraqi and Afghani gene banks were destroyed or at least very much harmed by the wars there. Seed banks in a way are a little bit like libraries and every once a while something bad happens to an individual book in a library and, likewise, even in a really great seed bank something bad will happen to a particular sample just by accident or mismanagement. And every time something bad happens like that, we lose that variety. In other words, it's an extinction event. We don't talk about saving a representative sample of Rembrandts and Goyas. We would like to save them all and ditto with agricultural plant diversity. We want to save all of that diversity. They’re all treasures.

PALMER: You point out that Norway is the ideal country, both to host this and has the ideal place to put it, and indeed is accepted by the international community as an honest broker. Why is that so?

FOWLER: Norway has always played a really positive role in international discussions and debates frankly about how to conserve this material and how to exchange it between countries. It's a fairly contentious issue, believe it or not, and countries are formulating rules about how to and under what circumstances and conditions to exchange crop diversity. No country on Earth has the requisite amount of crop diversity to fuel their own plant breeding programs into the future and that includes the United States. So, every country on Earth is dependent on other countries, are interdependent with the globe, to secure the biological foundation of its own agricultural system. So Norway's played a great positive role in that and Norway provided the perfect conditions and not coincidentally, it also provided the funding for it, and we needed that.

PALMER: So tell me about Svalbard. Where is it and what is it exactly?

FOWLER: Svalbard is a group of islands, and if you look at a map, or you have a globe handy you go to the North Pole and look just a little bit southward. So if you were in Oslo, Norway, which most people think of as far north, you would need to fly about 1,300 miles north of there to get to Svalbard. The seed vault itself is located at 78 degrees North and it's the farthest North that you can fly on a regularly scheduled airplane, albeit only about once a day, and it's a remarkably beautiful exotic otherworldly place. It can snow on any day of the year. This is an area that’s twice the size of Belgium and about 60 percent covered with glaciers. Still, great infrastructure, very safe, secure. It was just the ideal location.

PALMER: It has to be said we're in an era of global warming. How safe is Svalbard for global warming? I mean, we hear about glaciers melting all over.

The seed vault contains more than a half billion seeds. (Photo: Mari Tefre)

FOWLER: Oh yes, well, Svalbard is not safe from global warming, no place on Earth is, but the idea with the seed vault with all the good seed banks around the world is that you want to freeze the seed down to about minus three or four Fahrenheit, minus 18 Celsius and there's no place on Earth where you can do that naturally without mechanical cooling. So the challenge then is simply to find a place that gives you naturally cold temperatures, as cold as you can get, and from there you have to lower it a little bit further. So that's what we have in Svalbard, and the permafrost, we've built a tunnel that goes 130 meters into the mountain. It's a bit below freezing there. It's about minus five Celsius, and so even at that temperature, if our mechanical freezing were to fail, it would take months and months and months for that facility to warm up to something still below freezing, and even at that rate we calculate the seeds would be safe for decades. So we’d have a long time to fix the problem.

PALMER: There's one kind of irony and that is that the cooling that you have in the vault is actually powered by coal, and one of problems we've got of course, is global warming, and coal is one of the dirtiest fossil fuels we’ve got. Has this ever come up as an issue?

FOWLER: Well, we have to power the facility in some way. It doesn't take much. We don't have a big electricity bill, and there is a village up there that has to be powered and electrified, of course, and coal is local, it's locally mined. So, we're not shipping oil over the ocean to power that facility, and in a place like that where you have three months of polar night every year, it would be pretty hard to run it solar.

The vault houses more than 860,000 seed samples packed in boxes placed on shelves. Each sample packet contains 500 seeds. (Photo: Jim Richardson)

PALMER: I've looked at the pictures in the book and they are stunning. I mean, it's very bleak and large and colorful and lots of northern lights, and lots of polar bears and not many people.

FOWLER: That's true. There are, I think, more polar bears than people and certainly more reindeer up there than people, and when you're up there particularly if you leave the little village you will have I think an emotional experience that few people on Earth have these days, and that's an experience that comes from being untethered to civilization, and you realize you're really out there, you get a pretty profound feeling that you're on your own and that nature is in control and that nature is a little bit bigger and more powerful than we are individually. It'll have quite an impact on you.

PALMER: So you’ve got this vault at the end of a 300 foot tunnel more or less. What exactly is it? What does it consist of?

FOWLER: At the end of the tunnel we have three vault rooms, and each vault room is, well, about 30 meters long, 10 meters wide and five meters high, and we're only storing seeds in one of those vault rooms.

Everything about the seed vault has a lot of built in redundancy, so I did some calculations about how much space we would need to store all of the agricultural seed diversity in the world, and we have about three times as much storage space as my estimates indicated we would need because, well, I could be wrong. And when you walk into this final chamber it's extremely cold and it looks a little bit like a warehouse, frankly. We have shelves and we have boxes in the shelves, and each box contains about 400, 500 seed samples.

There are three main tunnels within the Svalbard Global Seed Vault (Photo: Mari Tefre)

They're all in individual packets, about 500 seats per packet, so currently I think we have about 500 million seeds down there, quite a few tons. And the boxes, they're pretty. They come from countries all over the world, and they have their little insignias on it, and when you walk down the aisles, you have to walk down the aisles with some humility because what you're seeing is the results of agricultural evolution over the last 15,000 years. It's essentially a biological history of agriculture, but it's also everything that agriculture can be in the future is represented in that diversity.

PALMER: Has every country bought into the idea of the need to preserve this seed heritage?

FOWLER: Well, the seed vault has seeds that are sourced from just about every country in the world including some countries that no longer exist, but that doesn't mean that every institution in every country has participated yet, and I think eventually they will. One of the other aspects of the management plan that we had to work out was a question about property rights. Who owns the seeds? So the way that we set up the seed vault was it would function like a safety deposit box at the bank where Norway owns the facility itself. In other words, it owns the mountain, but the individual depositor would own their seed deposits themselves and they and only they would have access to those seeds deposit.

So we don't send the United States collection to Canada or vice versa or whatever, but some countries simply take longer than others to come around to that that idea had to work through the bureaucracy so I'm not too worried about that, but I think we have a fairly good sample of the diversity in the world. I mean, we're looking at more than 150,000 different different types of rice, and more than 150,000 different kinds of wheat and I think about 35,000 different bean varieties and on and on.

PALMER: So why do you need 150,000 varieties of wheat or rice?

FOWLER: We need that kind of diversity because we don't have a crystal ball about what the future will bring. We know that there are always surprises, that agricultural crops they're evolving as are the pests and diseases that strike them. And with global warming, we're seeing the natural range of pest and diseases change and so new assemblages of species are coming into being and we don't know how crops are going to react to that, and human beings change their tastes and the food industry changes its requirements over time and all of that means that we need different traits, and so this diversity is a little bit like an artist’s palette. We want as many colors as possible so that we can create new paintings and every time you take away a color, every time you take away diversity you limit your options and there have been cases in our lifetime where we've had to search the entire collection of a particular crop and have only been able to find one variety containing particular genes, in other words, traits, that are needed to essentially rescue the crop.

Different varieties of wheat are stored in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. (Photo: Marc Di Luzio, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

PALMER: Some people would argue that science has been able to breed new varieties. You don't think science could just be the answer here? You think we need nature?

FOWLER: Oh, I love science and I have a lot of respect for it, and this diversity is used by scientists every day both in basic biological research but also traditional plant breeding. But we're not gods and not only are the individual genes, traits, important but I think we're, in the future we're going to learn a lot and benefit a lot from understanding the combinations of traits they have been assembled by our ancestors. Our diverse...our old heirloom varieties of grains and fruits and vegetables and such are the result of countless evolutionary experiments and they are the successful results of those experiments. So we have much to learn and I don't think we're going to have a substitute for this diversity anytime soon.

PALMER: How much genetic variety have we actually lost?

FOWLER: I don't know how much variety or diversity we've lost because frankly we never had a head count on it to begin with. We do have some records, at least in reasonably modern times. If you go back to the 1800s, the US Department of Agriculture was essentially doing a census of the varieties of fruits and vegetables that were grown by American farmers and we know we've lost a great deal of those varieties. I would make a distinction that varieties and diversity aren't quite the same thing because you can have a trait that appears in more than one variety of apple, for example. So losing a variety of apple doesn't mean you've lost that trait necessarily, but in some cases of course it would.

PALMER: Are you still collecting? Are there any other seeds you would really like to get?

FOWLER: Absolutely. There's always more diversity out there. Diversity is cropping up all the time so this task will never really end. We would like to get more of the wild relatives of our domesticated crops, they're pretty tough plants and in a situation where the weather is bad or there's global warming, those kind of traits are really interesting and useful for agriculture. Some of the very minor crops, we don't have good collections of some of those so I'd like to add to those, and there are a few countries that haven't participated in the seed vault yet. It doesn't mean that we don't seeds that were collected by other institutions in those countries, but we don't have those country’s collections as well so we want to add China and India and Ethiopia, Iran, to that list of course.

The seed vault is tucked into a frozen mountainside on the Svalbard archipelago. (Photo: Mari Tefre)

PALMER: When you say minor crops, what are you talking about?

FOWLER: Some of the vegetables, for instance, there's a whole category of African leafy vegetables. There are minor crops that you probably never would've heard of, I mean, Bastard Cabbage and Mormon tea and Love Lies Bleeding and Cheesy Toes, maybe these are forage crops but these are exotic names and I don't really know much about those as well, but we could use some more diversity of things like that.

PALMER: How long will the seeds stay viable in the vault?

FOWLER: It depends on the species. At the short end, some species would be fine for maybe 7,500 years or more. Our major grain crops, if you look at rice or wheat, barley, those should be viable somewhere between one and 2,000 years from now. Sorghum we estimate would be viable more than 19,000 years from now. Having said that I would add that this is not a time capsule, so yes eventually, even if eventually is 2,000 years from now, the seed will lose its ability to germinate. But what we've tried to do with the seed vault is to establish a facility whose conservation standards are equal to or better than any of the depositing institutions. So, in other words, the seeds in the seed vault will decline in their germinability no more quickly than those in in the best seed banks around the world and those seed banks monitor their seed supplies all the time so when they see that a seed sample is declining and its liability, they will take some seats outgrow them in the real world, multiply them and when they do that they'll send more seed to the seed vault. It's a living facility and will always have seed coming in.

PALMER: So it's constantly being replaced as it were. Does it also work as a kind of lending library of seeds?

In 2015, the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) became the first seed bank to withdraw seeds from the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Conflict in Aleppo, Syria forced the organization from its facility there. (Photo: Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

FOWLER: That's a good analogy. It is a library but the lending library portion of it really is up to the depositing institutions. It's pretty impractical to go to the North Pole or Svalbard to get seeds if you need them for a research project or plant breeding, so you would go to that normal national seed bank or one of the international research centers to get the seeds directly there. This is the backup, this is the insurance policy for all of those, but mostly we built the facility not thinking about doomsday or anything like that. That word doesn't appear in any of the planning documents. We built it because doomsday really occurs on an almost daily basis and one of the hundreds of seed banks around the world where they're losing the sample here and there, and that might be the sample that not just that country but all of humanity needs for that particular crop. By the way, we have had our first withdrawal of seeds and that was both a sad and a happy occasion. It was sad that the withdrawal needed to take place. It was happy that we had the backup copy so the collection and in question wasn't lost.

PALMER: So, who needed to withdraw seeds?

FOWLER: There was a wonderful international institution located outside of Aleppo, Syria, with the acronym ICARDA, the International Center for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas. This was not a Syrian facility, this was an international facility and they specialize in conserving and breeding wheat, barley, lentils, chickpea and a wonderful crop called grasspea or Latherous, major suppliers for farmers in that region particularly working on drought tolerant varieties which are of course very important and food security in the Mideast is of global importance.

So when the war came to Syria the researchers had to abandon their research station, but fortunately we had anticipated that there might be a problem then we worked with that institute to get a spare copy of all their seed samples out of Syria and up to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault before the fighting really started, and they reestablished their center in Morocco and Lebanon and of course they don't have access to the seed bank in Syria anymore so they really needed to start to get their seed supplies back and we shipped them back in September 2015, and they will multiply those seeds and they'll start to use again in their own research project and then as you can imagine they will be rather highly motivated to send us a copy back again.

Old coal transport infrastructure contrasts with the ice and snow of the mountains near the town of Longyearbyen, Norway. Coal is plentiful in the Svalbard archipelago and powers the seed vault. (Photo: Mari Tefre)

CURWOOD: That's Cary Fowler, author of "Seeds on Ice: and the Svalbard Global Seed Vault" talking with Living on Earth's Helen Palmer. Cary Fowler insists that Svalbard is not a doomsday vault though I’m probably not the only person reassured that such a facility does exist.

Related links:

- Seeds on Ice: Svalbard and the Global Seed Vault

- More about the Svalbard Global Seed Vault

- CNN: About ICARDA’s withdrawal of seeds following its move from Aleppo, Syria

[MUSIC: Natraj, “Ava De Se,” from The Goat Also Gallops, West African traditional/transcribed David Locke, Dorian Discovery Recordings]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Aidan Connelly, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Emmett Fitzgerald, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Alex Metzger, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. Special thanks this week to One Ocean Expeditions. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page -- PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth