November 25, 2016

Air Date: November 25, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Blackfeet Tribe Regains Sacred Land

View the page for this story

The Obama Administration has cancelled oil and gas leases on 30,000 acres of Montana’s Badger-Two Medicine region near Glacier National Park, land the Blackfeet Nation considers sacred. Blackfeet Tribal Council Secretary Tyson Running Wolf discusses the significance of this decision with host Steve Curwood, as well as the next steps for ensuring the area is protected for the Blackfeet people. (07:00)

Leasing U.S. Lands for Sunshine

View the page for this story

New regulations have been issued by the Bureau of Land Management for leasing on public lands for solar and wind energy development. The new rules are intended to make it easier for developers to get financing, and restrict leasing to lands not needed for conservation. Energy Fellow Jennifer Macedonia of the Bipartisan Policy Center spoke with Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood about the appeal of the rules to both Democrats and Republicans alike. (05:15)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood discuss how the recent US elections brought unexpected outcomes for environmental groups and fossil fuel companies alike, and remember the events that inspired an iconic American folk song that became a Thanksgiving tradition. (04:30)

High Tech Rain

View the page for this story

For the millennial generation, nature is not the pristine grand wilderness it was for writers like John Muir. But they are relating to the natural world in new ways, and in this essay from Coming of Age at the End of Nature, writer Megan Kimble dissects her growing concern about the efficacy and ethics of creating “artificial rain,” through a process known as cloud seeding. (06:25)

Plants Fight Climate Change

View the page for this story

New research finds that plants are absorbing more carbon dioxide as atmospheric levels have risen, helping to counteract some of the extra CO2 humans are emitting. But as scientist Trevor Keenan tells host Steve Curwood, rising temperatures will soon hinder plants’ ability to take up excess carbon dioxide. Because many countries are banking on their ecosystems’ ability to absorb CO2, that could have serious implications for the world’s climate protection plans. (06:00)

Farming Carbon

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

Carbon farming describes the agricultural practices that bank carbon in the soil and biomass of farmed crops, and thus blunt global warming. Backyard farmer Eric Toensmeier is trying these methods in his own garden, trying to store as much carbon in his earth as gardeners more easily achieve in warmer climates. Living On Earth’s Helen Palmer took a tour of Eric’s home garden in Holyoke, Massachusetts for a crash course on growing perennial plants in temperate climates. (17:45)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Tyson Running Wolf, Jennifer Macedonia, Megan Kimble, Trevor Keenan, Eric Toensmeier

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Helen Palmer

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The Obama Administration and industry co-operate to cancel oil and gas leases in Montana’s sacred and stunning Blackfeet Indian Country.

RUNNING WOLF: I would say that it's the Swiss Alps of the North American continent. It's so dramatic where the Great Plains meet the Rocky Mountains, with beautiful blue lakes, nice green forests and a vast cultural history of Blackfeet people.

CURWOOD: Also, how extra CO2 in the atmosphere has revved up photosynthesis in plants to help slow global warming.

KEENAN: We've known for decades that ecosystems are taking up a lot of the carbon dioxide we emit into the atmosphere. What we didn't think was possible was the extent to which they could take up carbon dioxide. So, in the past decade they've taken up more carbon dioxide than ever before.

CURWOOD: But this extra carbon uptake may not last. That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

CURWOOD: That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Blackfeet Tribe Regains Sacred Land

Train crossing Two Medicine trestle over the Two Medicine river (Photo: Loco Steve, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. As the Standing Rock Sioux continue to protest the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline in a watershed they consider sacred, another Native American nation is celebrating a win for its own holy lands. The federal government has now cancelled 15 oil and gas leases on land the Blackfeet Nation reveres in the Badger-Two Medicine area, near scenic Glacier National Park in Montana. The move caps two years of intense negotiations among the Blackfeet, Secretary of Interior Sally Jewell, Montana Senator John Tester, and Devon Energy, which owned the leases, but had never drilled. Tyson Running Wolf is Secretary of the Blackfeet Tribal Council and joins us now from Browning, Montana. Tyson, welcome to Living on Earth.

RUNNING WOLF: Thank you. Glad to be on with you guys.

CURWOOD: Well, congratulations. Now tell us about the Badger-Two Medicine area and why it's important to the Blackfeet nation.

RUNNING WOLF: The Badger-Two Medicine is an area that is located just to the southwest of the Blackfeet reservation and south of Glacier National Park. It covers about 168,000 acres and includes a lot of our cultural, spiritual areas for the Blackfeet people.

CURWOOD: This is dramatic territory, right? It's pretty close to the Bob Marshall Wilderness?

RUNNING WOLF: Yes, it's just to the north of the Bob Marshall Wilderness and it is on Rocky Mountain front and butts right up to the Continental divide.

CURWOOD: So, this is territory with grizzly bears and amazing fish and all kinds of wildlife. I've been to the Bob Marshall. If it's anything like that, it's pretty wild.

RUNNING WOLF: Yes, I would say that it's the Swiss Alps of the North American continent. It's so dramatic where the Great Plains meet the Rocky Mountains with beautiful blue lakes, nice green forests and a vast cultural history of Blackfeet people. It is unique. It's tough. It's steep and has some threatened and endangered species, including the Blackfeet. [LAUGHS]

Blackfeet Indian Reservation (Photo: Murray Foubister, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] You mean your nation is endangered.

RUNNING WOLF: We always feel like it, so we always work really hard to try to preserve and protect us as Blackfeet people.

CURWOOD: Now, why would development of those oil and gas leases have been damaging to the Blackfeet nation in the area?

RUNNING WOLF: If there's oil and gas development that happened in there, and there was a malfunction or something went wrong, it would compromise the Badger and the two Medicine rivers, two major drainages that we hold very dear to us that flows down and connects into the Missouri drainage, and also the Birch creek system which always seems to get left out, as Birch Creek is also a big part of that.

CURWOOD: To what extent is this a sacred land for the Blackfeet Nation?

RUNNING WOLF: This area is a lot of our spiritual area that we go for solitude. A lot of our people go there for different ceremonial purposes, also for gathering medicines that we have back there. Also for the relationship of animate and inanimate objects that are back there that we have passed down for generations upon generations of how we use them and what kind of relationship we have with them for the betterment of Blackfeet people.

CURWOOD: As I understand it, you and your fellow Blackfeet leaders consider these oil and gas leases to have been granted illegally back in 1982. Explain that for me, please.

RUNNING WOLF: We felt the leases were illegally let to individual leaseholders on oil and gas because they didn't consult the tribe. They didn't let us know what was going to happen back there. The federal government didn't follow their own process on how to involve Blackfeet people on land that we still feel is owned by the Blackfeet themselves.

CURWOOD: Tell me, how long has the Blackfeet Nation been on this land, do you think?

RUNNING WOLF: We have documented historical data that we've been here for 10,000 years or longer.

CURWOOD: So, eventually you got to sit at the table with, what, the Secretary of the Interior, your Senator from Montana John Tester, and the company that had owned these leases, Devon Energy. What was the key to getting this deal together once you got to the table?

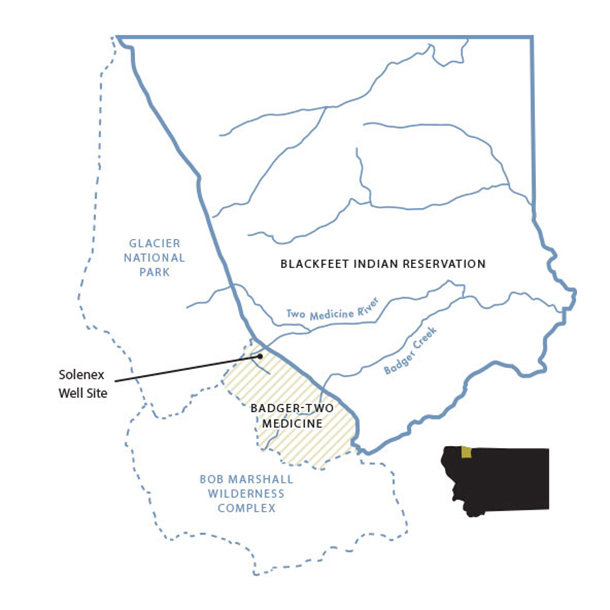

The Badger-Two Medicine area is adjacent to Glacier National Park, the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex, and the Blackfeet Indian Reservation. (Photo: Blackfeet Nation)

RUNNING WOLF: The key was relationship of understanding each other's reasons for protecting certain areas of the rich cultural importance that the Blackfeet have in the area, and also what Department of Interior and the US Forest Service, knowing that it's a very special place also with the hard work of John Tester and his connections.

CURWOOD: Tyson Running Wolf, I understand there still are a couple of oil and gas leases in the Badger-Two Medicine area. How much of a threat do those leases pose to the Blackfeet nation and this land?

RUNNING WOLF: Yah, them leases...There's 11,000 acres still out there held by two companies. It is just as important as the 32,000 acres that was just canceled. The whole 168,000 acres is still compromised with having them two leases available to lease.

CURWOOD: So, what's going on with getting those leases canceled? Who owns them and what are they saying?

RUNNING WOLF: I don't necessarily know who owns them. We have people out there researching that right now. We want to get them names and numbers of who owns them two particular, last leases, get them to the federal government, get them back to the tribal business council, and start engaging in some positive dialogue so that we could try to make something happen to where we can get these leases canceled right away.

CURWOOD: And, of course, when leases are canceled the folks get their money back and whatever extra fees they've paid.

RUNNING WOLF: Yes, they'll be compensated.

CURWOOD: What's next for the Blackfeet Nation's efforts to protect sacred lands including the Badger-Two Medicine area?

The Blackfeet people have been living on the Great Plains of Montana for at least 10,000 years (Photo: Edward S. Curtis, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

RUNNING WOLF: Co-management of the Badger-Two Medicine. That's the next thing we're shooting for. We always push on Glacier National Park which is to the north and also the Forest Service which holds in trust the Badger-Two Medicine. Now, we would like to put back to the two most important things on the landscape, and that's the buffalo and the Blackfeet. And we want to cooperatively work with both of them entities to make that happen. And any other management decisions, we want to be sitting at the table, and we also want to make sure that our people are right involved in the best interest of this tribe on what the direction of that landscape should be.

CURWOOD: Because, right now, much of the territory, especially, say, the Bob Marshalls Wilderness, no one is allowed to live there as I understand it.

RUNNING WOLF: That's correct.

CURWOOD: And, of course, this was your ancestral lands.

RUNNING WOLF: That was our ancestral lands, yup.

Buffalo graze on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation in Montana (Photo: Phil Roussin, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: And, by the way, in Blackfeet, what's the name of Badger-Two Medicine area. What you call it in your language?

RUNNING WOLF: So you’d say badger which is mees-kim, then you would say Two Medicine which is nat-tuk na-tuus. So it's "Mees-kim Nat-tuk Na-tuus".

CURWOOD: And the Blackfeet word for hope?

RUNNING WOLF: Hope? The Blackfeet word for anything of hope or survival is komo-tani.

CURWOOD: Well, I trust this adds to the komo-tani for the Blackfeet. Tyson Running Wolf is Secretary for the Blackfeet Nation. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

RUNNING WOLF: You betcha. Thank you.

Related links:

- The Blackfeet Nation’s website about protecting the Badger-Two Medicine area

- Department of Interior press release on the Badger-Two Medicine lease cancellations

- The Badger-Two Medicine area is part of the Lewis and Clark National Forest

- About the Blackfeet Nation

- Senator Jon Tester’s statement in support of the lease cancellation

Leasing U.S. Lands for Sunshine

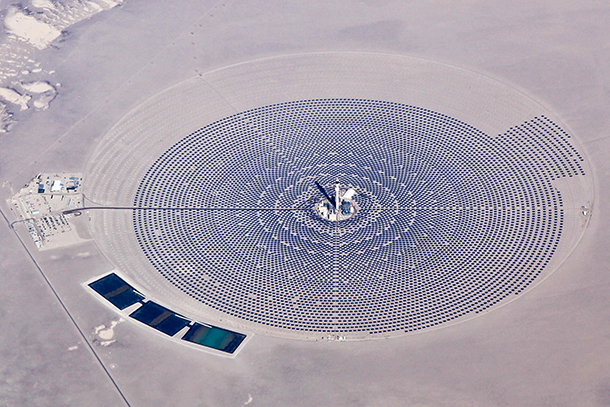

The Crescent Dunes Solar Project in Nevada is one of over 30 solar projects approved on BLM Lands since 2009. (Photo: Matt Hintsa, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Even as the Interior Department was canceling oil and gas leases in Montana, its Bureau of Land Management was setting new rules for the leasing of Federal lands for solar and wind energy. Federal land for renewable energy production will now be leased under terms more favorable for financing. The rules came in response to a review of sustainable energy production on public property that the Obama Administration began in 2012, though the incoming Trump Administration could block or change them, even though they have bipartisan support.

Some 14 Republican and Democratic members of Congress have endorsed the rules, so we called up Jennifer Macedonia, an energy fellow at the Bipartisan Policy Center to find out what is the bipartisan appeal of renting federal lands for sustainable energy.

MACEDONIA: Well, there is clearly bipartisan support for clean energy, and this rule shows that it's important and possible. This rule has been praised by environmentalists, some in industry, political leaders across the aisle. There were 14 House Republicans and Democrats hailed it as a win from both an environmental and economic standpoint in a letter to the Secretary of the Interior in June. So it has received bipartisan support. It's addressing both economic and environmental concerns that can raise revenue for the US as well as increased deployment of clean energy to help us all.

CURWOOD: Tell me exactly how these new rules reform the process of leasing public lands for renewable energy projects?

MACEDONIA: Sure. The main piece of it is that it brings in a competitive bidding process for renewable energy projects, and it's incentivizing that those projects occur on low-conflict land, which is land that has not already been set aside for wildlife or other uses, lands that are not going to have, for example, sage-grouse habitat or some conflict with an endangered species or other sensitive lands to be concerned about. So trying to incentive folks from doing leasing on these lands.

The American Wind Energy Association expressed disapproval over the new rules, claiming it offers advantages to solar that are unavailable to the wind industry. (Photo: Tom, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Tell me about the problems with leasing that occurred in the past that led to the Bureau of Land Management to have these new rules.

MACEDONIA: Well, without a competitive bidding process, someone who applies for a lease is really not...You know, whoever gets the first application in is the first one considered, essentially, for this track of land, and that's not always the best application. Secondly, because we're talking about potential conflicts with the Endangered Species Act, potentially sensitive lands, and wind and energy and solar development have complex environmental reviews associated with them to determine if there are any conflicts. So, this has tended to be a long process, it has made it more difficult to get through the process and in many cases people were more likely to look to private lands instead of public lands.

CURWOOD: Now, there's some solar and wind companies that are concerned about this rule. The American Wind Energy Association has said it will make federal land less attractive to wind developers because these rules are going to add time, uncertainty, complexity and cost to this process. How valid are those concerns do you think?

MACEDONIA: So, some in the solar and wind development industry would have liked the rule to go further in smoothing the way for renewable development on federal lands, not just in these pre-screened designated leasing areas. The rule is attempting to balance the need for time-consuming project specific reviews to protect wildlife and sensitive lands with the goal of encouraging renewable energy development. And to balance those needs, the rule settles on a dual approach where prescreened non-conflict lands get a green light, expedited process, and the rest of public lands still require jumping through more hoops.

CURWOOD: So, how likely is that the Trump Administration will see this as a useful rule and not want to roll it back?

MACEDONIA: There's a lot in this rule to like from a markets perspective. Part of the Trump energy platform is an all-of-the-above approach to energy, including wind and solar. However, Trump has said that he favors fossil fuel development on federal lands over wind, solar and geothermal, but he's not indicated that he would undo these rules.

Jennifer Macedonia is an energy expert with the Bipartisan Policy Center. (Photo: courtesy of Jennifer Macedonia)

Some of his past concern over wind energy in particular and conflicts with his Scottish golf course maybe raised some concerns particularly on the wind energy side, where they need some additional steps to be put in place to complement this rule to make it really effective for deploying wind energy, but there's a lot in here in terms of making it a competitive process, which is similar to the way oil and natural gas leasing on federal lands is done. It fits into the all-of-the-above approach to energy. It fits into using market-based approaches, so there is a lot that the Trump administration should want to keep in this rule and a lot of reasons for keeping it on the books.

CURWOOD: Well, I want to thank you for taking the time with us today. Jennifer Macedonia is an energy expert at the Bipartisan Policy Center in Washington, DC. Thank you.

MACEDONIA: Thank you so much. I have enjoyed talking with you.

Related links:

- Full draft of the new BLM Leasing Rules

- More information on Solar Energy Zones

- Statement from the American Wind Energy Association

- Bipartisan Policy Center Fellow Jennifer Macedonia

[MUSIC: Monika Jalili, “Biya Bare Safar Bandim” (“Let’s Be On Our Way”), on Elan, Mohammed Sarir/Ardalan/Sarfaraz, self-published]

CURWOOD: Coming up...welcome allies in the bid to cut atmospheric carbon. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Monika Jalili, “Prelude to Ay Rilikh,” (“Separation”), on Elan, Ali Salimi/Monica Gould, self-published.]

Beyond the Headlines

Both houses of Congress continue to be controlled by Republicans, many of whom are skeptical of environmental regulation. (Photo: Daniel Mennerich, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Time to take a trip to Conyers, Georgia now to find out about the world beyond the headlines. Peter Dykstra of DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, has been digging about there. So, Peter, what have you found?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. You know a few days ago, I took to Google to remind myself about how we’re sometimes, collectively, a lot less smart than we think.

CURWOOD: Oh, so what did you find on Google?

DYKSTRA: From months before the Presidential election, there was a unified theme, voiced by former President George W. Bush, by liberal pundits like Rachel Maddow and by conservative pundits like David Brooks. They all foretold the “Death of the Republican Party.”

CURWOOD: Seems to me that party now will now control the White House and both houses of Congress?

DYKSTRA: And likely the balance of the Supreme Court, and possibly most significant of all, the GOP is getting very close to controlling enough state legislatures to push through Constitutional Amendments. This is all happening at a time when the Republican Party is as anti-environment as it’s ever been. In the most recent Congressional scorecard from the League of Conservation Voters, of the 247 Republicans in the House of Representatives, none received a rating as high as 50 percent. Nearly a hundred Republicans had a score of zero for their environmental votes in the year 2015.

CURWOOD: Yet another sign that a lot of conservatives have apparently given up on conservation. Looks like the environmental advocates have got their work cut out for them, huh?

DYKSTRA: There’s no way to state that without it being an understatement, Steve. But let’s look at one realm where the big environmental groups and the big coal companies have something in common, post-election.

CURWOOD: I can’t imagine those two having much in common at all, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Well, both Big Coal and Big Green benefited from reactions to the election of Donald Trump. For big coal, it was on Wall Street. Peabody Energy’s share price shot up 59 percent the day after the election. Another big coal producer, Cloud Peak, rose by almost 18 percent. And those gains leveled off a bit, but still, a business that like the Republican Party was declared dead by a lot of pundits is once again showing some signs of life.

CURWOOD: Alright, well that’s Big Coal, what about Big Green?

DYKSTRA: Nonprofit environmental groups reported a surge in new members and donations and volunteers. The Sierra Club said it got as many new supporters in the week following the election as they’ve gotten in all of the rest of 2016 so far. The Environmental Defense Fund said its Election Week haul of donations doubled the total raised during those same days in 2015. This is in part due to these organizations seizing the opportunity to send out urgent funding appeals that they weren’t exactly expecting to have to send, and it’s part due to what you might call “panic” giving by individuals who were surprised and alarmed by the Trump victory. Other non-environment groups like Planned Parenthood and the ACLU report the same thing happening.

The Sierra Club, among other environmental nonprofit organizations, saw a surge in membership and donations after the recent election of Donald J. Trump as president. (Photo: Charlie Kaijo, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, Peter, these urgent appeals work both ways, right? I seem to recall the National Rifle Association getting a surge of new support after Barrack Obama was elected in 2008.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, not just support, there was a surge in new gun permits and purchases. Conversely, and this is a little off our normal topic but it’s relevant, gun sales plummeted once Hillary Clinton was no longer a threat, and stock in gun manufacturers like Smith & Wesson and Ruger shot downward, 10 to 20 percent losses in the days after the election.

CURWOOD: Hmmm, kind of sounds like that old stock tip, "buy on rumor and sell on news".

DYKSTRA: Yeah, perhaps. So Steve, how about a little history for this week?

CURWOOD: Sure, floor is yours.

DYKSTRA: Fifty-one years ago, November 26, 1965, saw the most famous act of littering in American history. A man named Richard Robbins and his accomplice, one Arlo Guthrie, dumped the remains of a Thanksgiving dinner that couldn’t be beat down a hillside in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Two days later, a local law enforcement investigation revealed an incriminating envelope beneath the pile of garbage, and Officer William J. Obanhein….

CURWOOD: Ah, the famous officer Obie...

DYKSTRA: Right, he apprehended the perpetrators, who were fined and released and ordered to pick up the garbage.

CURWOOD: And so we got the Alice’s Restaurant song, even the Alice’s Restaurant movie.

Folk singer Arlo Guthrie was arrested in 1965 for littering in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, an event that inspired his famous Thanksgiving and anti-Vietnam war story-song “Alice’s Restaurant.” (Photo: Fredercik Fenyvessy, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: And even the Alice’s Restaurant cookbook. And Officer Obie got to play himself in the movie, which along with the eighteen and a half minute song became Thanksgiving traditions and a strong political statement opposing the Vietnam War.

CURWOOD: All of this from a littering arrest. It’s a tribute to the power of music and art.

DYKSTRA: Yup.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks Peter, we’ll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: OK, Steve, thanks a lot. We’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories on our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Google results for “Death of the Republican Party”

- Coal stocks boomed after Trump was elected to the Presidency

- Donations to environmental causes rose after Trump won the election

- Why gun stocks dropped after Trump’s win

- Listen to Arlo Guthrie’s song “Alice’s Restaurant”

[MUSIC: Søren Bødker Madsen, “Alice’s Restaurant,” on Danish Guitar Performance, Arlo Guthrie, self-published and available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mjc_tk5Q9Mk]

High Tech Rain

Cumulus clouds drift over a country road (Photo: Susanne Nilsson, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: More than a century ago the powerful nature writing of John Muir and Henry David Thoreau and others inspired the protection of some of the most scenic treasures of the American landscape. But ever since Bill McKibben wrote “The End of Nature,” in 1989, there’s a new realization that no part of the landscape is untouched or unaffected by humans. Writers of the millennial generation came of age in the shadow of this mediated nature, often growing up in urban landscapes, during economic recessions, where the “end of nature” can seem all too real. And a recent anthology of essays by millennials, called Coming of Age at the End of Nature, shows them engaging in new and urgent ways with their surroundings. Today we have another of these essays.

KIMBALL: Hi, I'm Megan Kimball. I'm a writer living in Tucson, Arizona, and here is an excerpt from my essay, "The Wager For Rain".

On a Monday morning in September I am reading a layperson's guide to Arizona water, and I am stopped in my tracks by the dream of cloud seeding. I'm a layperson in both senses of the word, neither an ordained minister of a church nor a professional academic, but I suppose that the University of Arizona's water resource center does not intend to confer religious overtones to the subject of creating water in the desert.

A plane equipped with a silver iodide generator for cloud seeding (Photo: Christian Jansky, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.5)

Water officials predict a very precise 25 percent chance that water supply won't meet demand within the next 10 years, but we are reassured. "Scholars believe that when the Hohokam population grew beyond its ability to stretch its limited water supplies, the civilization failed, but these early desert dwellers lacked the technological resources of contemporary water managers, and Arizona is now developing new ways to manage and extend this scarce resource.

I scrawl in the margin, "But this won't happen to us. Technology will save us." I realize it is the resources of contemporary water managers that allow water to flow freely out of my faucets, but alone in my apartment it is too easy to criticize human hubris.

"One technology is cloud seeding. Cloudseeding injects chemicals such as silver iodide into clouds to allow water droplets or ice crystals to form more easily, increasing precipitation." I have never heard of cloudseeding, and I am scandalized or entranced by the idea. It is as if I was not the only wide-eyed seven-year-old how believed in the possibility of man-made rain.

Though cloudseeing has been appropriated by academics at the University of Arizona and elsewhere, it's hardly the first attempt to stir up rain in the desert. Cloudseeding is technological rainmaking. Starting with the first people who settled here, the Hohokam, indigenous civilizations have practiced elaborate ceremonies to entice rain from the clouds.

[MUSIC: Southwestern U.S. Native flute music.]

We may well dismiss the rainmaking as the religion of a failed civilization but the Tohono O'odham, another people who have lived off the desert land for centuries, are very much still live and flourishing and continue to perform rainmaking ceremonies every year. Music, cactus wine, and dancing are the seeds to their clouds. Maybe I am stopped in my tracks on a Monday morning because, contained within this layperson's guide, cloudseeding feels no less religious to me than a raindance.

A man operating a ground-based iodide generator (Photo: By Esteban9, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

You know, people refer to the church of cloudseeding, people refer to the believers in cloudseeding. I had one scientist say that when I said, "Do you believe in cloudseeding?" He said, "I'm an agnostic." The western United States are spending about $15 million on cloudseeding, and still there is no consensus in the scientific community about whether or not it works. Water droplets form around something called the condensation nuclei, and usually those are ice crystals or particulates in the air, and cloud seeding is artifically injecting those condensation nuclei into the atmosphere. So, seeding involve injecting particles, which is typically silver iodide, into the clouds to provide this nucleus around which rain can gather and then fall.

[SOUNDS OF CLOUD BURST AND TORRENTIAL RAIN]

Since the 1970s, scientists have been trying to measure how much rain falls when you seed clouds, um, and the problem with that is that you can throw up a bunch of silver iodide, and you can measure how much rain falls. But what you can't measure, what is significantly harder to measure, is the rain that wouldn't have fallen if you didn't see the cloud, and you also can't measure where that rain wouldn't have fallen otherwise had you not made it rain in this particular place.

Megan Kimble is a writer and editor of the magazine Edible Baja Arizona (Photo: Megan Kimble)

[MUSIC IN THE BACKGROUND]

You know, there's an adage in the west that water flows toward money, and this is an example where we have decided that rain is going to fall on money. We've created legislation to divvy up ground water in rivers, but we have no regulation over who controls the sky and who has access to rain. So, you have to have $15,000 on the smallest scale to get a silver iodide machine to cloud seed. So what does that mean in terms of people who don't have that kind of money? Farmers who, one neighbor is going to seed his clouds, and then the the farm adjacent to him isn't going have access to that rain. There are also much larger scale programs by ski resorts, for example, in the Colorado Rockies. Lots of western states have million-dollar weather modification programs.

I feel very skeptical that technology will save us. Cloudseeding is a good example of how we deploy technology, convinced that it will work, that it will produce more rain, and we haven't measured that to be true. Not heeding the examples of civilizations like the Hohokam and the O'odham -- When you run out of water and your civilization collapses -- is a great example of pride that makes me really nervous.

[MUSIC: Merrill Garbus, “Water Fountain,” on Nikki Nack, 4AD]

CURWOOD: That’s writer Megan Kimble. Her essay is part of the collection “Coming of Age at the End of Nature, A Generation Faces Living on a Changing Planet.”

[MUSIC: Merrill Garbus, “Water Fountain,” on Nikki Nack, 4AD]

Related links:

- Wyoming pushes forward with cloud seeding initiative

- Los Angeles using cloud seeding to quell the draught

- Article from Bloomberg on the growing cloud seeding industry

- About Megan Kimble

Plants Fight Climate Change

Plants absorb more carbon dioxide through photosynthesis when atmospheric levels of the greenhouse gas are higher – until warmer temperatures begin to counteract this effect. (Photo: 16:9 clue, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

In January of 2015 scientists found some 400 parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, up from the 270 parts per million when the Industrial Age began in the late 1700s. All that extra CO2 in the air is warming the planet at a dangerous rate, scientists tell us, but we may have gotten a period of grace, thanks to green plants. Using photosynthesis, green vegetation soaks up carbon dioxide, and new research suggests that over recent decades rising CO2 levels have helped plants ramp up photosynthesis and slow the rate of global warming. But don’t expect the trend to last. According to researchers at the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, it will soon be too hot for plants to keep absorbing so much added CO2. Trevor Keenan, the lead author on this research, is a Global Change Ecologist at the Lab and joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

KEENAN: Thank you very much. Great to be here.

CURWOOD: So how excited are you by these results?

KEENAN: Well, these results are very exciting. We've known for decades that ecosystems have been taking up a lot of the carbon dioxide we emit into the atmosphere. Now they are not taking up near enough to really stop climate change, but they are going slowing it down significantly.

The world’s plants have been absorbing extra carbon dioxide for the last few decades. (Photo: Neil Palmer/CIAT for Center for International Forestry Research [CIFOR], Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: What if plants weren't doing this, taking up all the CO2. Where would we be?

KEENAN: We would be about 460 parts per million already. That's something we don't expect until about 2050 or 2060.

CURWOOD: How does this work scientifically? I mean, how can these plants increase the amount of carbon dioxide they are absorbing?

KEENAN: There are two effects. One is the plants use atmospheric CO2 to grow and to support their metabolism. So, they take CO2 to from the atmosphere, using a process called photosynthesis. The other major process that's involved is respiration. So, plants and microbes respire CO2 back into the atmosphere, and this is highly dependent on temperatures. So, as CO2 is going up, plants take more CO2 from the atmosphere, but as temperatures go up they also release more CO2 into the atmosphere because of the effect of temperature on respiration.

CURWOOD: So, in other words, it sounds like more CO2 will go into plants as long as temperatures stay low. But, if temperatures start to rise, then they won't be so interested in this, huh?

KEENAN: Exactly. As temperatures rise with CO2, that has a net negative effect on the carbon balance of the land surface and on ecosystems.

CURWOOD: So, how reassuring should this news be, if at all?

KEENAN: Not very. It's a period that is quite temporary. We expect temperatures to continue to increase in the future and they already have over the past two years with the large El Nino event we've seen globally, and the net effect of this is a release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. A lot of carbon goes into soils, and these soils are respiring. And dependence on temperature, and as temperature rises, that carbon that has been stored there could be released back into the atmosphere. That's super important because in the Paris Agreement that was signed recently, two-thirds of the countries said they would use the land sink to help them in their mitigation efforts.

If plants weren’t absorbing extra carbon dioxide, atmospheric levels might have already reached 460 parts per million, a level they aren’t projected to reach until the mid twenty-first century. (Photo: Brent Moore, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Trevor, how were you and your colleagues able to determine that plants have increased their uptake of CO2 over these past few decades?

KEENAN: So, we have really good measurements of the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. This has been measured very accurately over five decades since the ‘50s. And by examining changes in the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere over time, we can infer what is happening on the land surface and the oceans because we also know how much we're emitting into the atmosphere.

CURWOOD: Yes, so that raises one question. How do you know what's going into the ocean versus what's being taking up on the land here?

KEENAN: Primarily from a modeling approach. So, ocean models tend to agree very well with each other, and there's also a lot lower variability from year-to-year in the ocean than there is on land, so it's proportionally more easier to estimate how much carbon is going into the ocean. On lands, however, models disagree quite a lot, and there’s a lot of variability from year-to-year.

CURWOOD: Trevor, are you able to differentiate which plants are doing the best in this increased CO2 regime? In other words, are they big trees that are getting even bigger because of this, or are they little plants, grasses. Where do we see this uptake?

KEENAN: So, it's really not known. It is very complex to detect changes in biomass stocks over time. For example, estimates from satellite data and atmospheric data would say that a lot of this carbon dioxide is going into the tropics, but, when you measure tropical biomass over time, reports show very conflicting results. We also see greening at higher latitudes as the Earth warms, and these temperature limited systems are beginning to green, so a lot of carbon dioxide could be taken up by this new vegetation. And also in semi-arid regions, so regions which are water limited because increased CO2 in the atmosphere, another effect that it has, is makes plants more efficient at using water, so more vegetation can survive in regions that previously couldn't.

CURWOOD: Now, to what extent make this finding be misinterpreted by climate action skeptics and cited as evidence that CO2 is actually good for the planet, as some have suggested?

Trevor Keenan is a scientist in the Climate and Ecosystem Sciences division at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. (Photo: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory)

KEENAN: Well, climate skeptics are keen to use whatever tidbits of information they can to justify their message, but ultimately it will be taken completely out of context. In any warming systems, especially a system as complex as the Earth's climate system, you expect brief periods where there is no warming apparent. Those periods ultimately end because the system is on the upper trajectory. So, although they could use results to say that CO2 is good for plants, it's really missing the whole picture. CO2 introduces warming locally, which as we know it is very detrimental, especially as we move further into the century and the kind of extreme temperatures we expect to see because of the CO2 is most definitely detrimental to plants, due to increased drought mortality, increase that fire frequencies globally. It really is quite a scary scenario we're looking at.

CURWOOD: Trevor Keenen is a Global Change Ecologist at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

KEENAN: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- Nature Communications journal: “Recent pause in the growth rate of atmospheric CO2 due to enhanced terrestrial carbon uptake”

- The AmeriFlux Network measures carbon dioxide in North, Central and South America

- About Trevor Keenan

[MUSIC: La Musgana, “La Rueda del Tiempo” (The Circle Of Time”), on Temas Profanos, Lubican Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up...harnessing farm power to fight global warming. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney, and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward.

This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Alasdair Fraser/Paul Machlis, “The Scolding Wives of Abertarff,” on Skydance, traditional Scottish melody, Culburnie Records]

Farming Carbon

Eric’s garden features a greenhouse for indoor growing. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. As the concern about rising CO2 turns to alarm in places, experts are studying possible ways we might reduce it in the atmosphere. Several countries are looking to agriculture and farms and forests as part of the answer. Now, a large and comprehensive book, "The Carbon-Farming Solution" probes and analyzes the potential of perennial crops and agro-forestry to sequester carbon from the atmosphere. Its author, Eric Toensmeier is using his own garden in Holyoke, Massachusetts, as a demonstration of what can be done, even with just a tenth of an acre of land. Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer paid Eric a visit to find out all about it.

PALMER: The first hint you get that there’s a mystery behind Eric Toensmeier’s stucco covered house when you drive up there are the large lush leaves of an eight-foot banana plant in the front yard – unusual for suburban New England. But it shows what carbon farming means, agriculture to remove excess carbon from the air and soil and store it in trees and plants. It’s a form of permaculture, mirroring natural and traditional systems that enhance and nurture the earth.

TOENSMEIER: None of these techniques were developed for the purpose of sequestering carbon.

[BACKGROUND SOUNDS OF CHILDREN PLAYING AND OTHER ACTIVITIES]

They were all designed because they do something important on the farm. So increasing organic matter in the soil is already a good idea on the farm, incorporating trees in the right way and in the right context can increase the productivity of the farm quite a bit. Studies in France have found, for example, that when you combine annual grain crops with timber trees and you have the spacing right, on 100 acres you could produce the same amount of grain and timber that would take 130 to 140 acres to produce if they were grown on their own.

A banana tree sprouts from Eric’s front yard. (Photo: Jaime Kaiser)

PALMER: Those of us who live in cold climates with a small backyard find practices like inter-planting woody trees and grain crops foreign, and, geographically speaking, they are. The most successful and efficient carbon-sequestering farms and gardens are in humid and tropical climates, such as India, parts of Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean.

TOENSMEIER: My wife’s family has one in Guatemala and it’s the most unremarkable thing there, but I could go and get a PhD walking around in there because it’s so fascinating. Their multi-strata agro-forestry system with multiple layers of trees and shrubs and vines and herbs is the very best system for sequestering carbon that we have agriculturally. In fact some studies have found certain instances where tropical home gardens actually sequester more carbon than natural forests nearby. So, they can be very powerful, and yet we don’t have a lot of commercial models yet in cold climates, and so that’s been a lot of my work the past 25 years.

PALMER: Large-scale commercial agriculture in much of the world and certainly in the U.S. features annual, often commodity crops that depend on widespread use of chemicals. Think corn and soy beans, though it can also mean apple and almond orchards. And it produces a lot of food.

Eric nurtured his garden from a bare plot of land. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

TOENSMEIER: Productivity per acre is very high and that’s great because that allows us to minimize deforestation to clear land for more agriculture. And many would argue that more fertilizer and pesticides would help us do that. My personal approach that I advocate in the book is that there are agro-ecological practices that also intensify, grow more on the same land, without increasing those less environmentally friendly aspects of agriculture as we know it today.

PALMER: One traditional practice Eric is using here is growing perennial plants. Plants that last more than one growing season, and he often uses edibles you can’t find in seed company catalogues. But in the United States, the yields of perennials can’t compete with annuals yet, so his garden is a kind of informal research project where he’s out to match the carbon-capture potential of the home gardens in the tropics.

TOENSMEIER: Mostly perennial crops are not really interesting to big seed companies, partly because perennials, once you buy the seed, you don’t have to go back and do it again so it’s not their priority, and big seed companies aren’t working on developing perennial kale, let’s just say.

PALMER: [LAUGHS] Well we should go and have a look at your plot. You are demonstrating some of these potential ways of carbon farming in your own backyard.

TOENSMEIER: Great.

PALMER: I follow Eric behind his greenhouse first, through a green tunnel of tall shrubs and fragrant flowering plants.

TOENSMEIER: This is a little patch that has some plants that attract beneficial insects. These are mountain mint, which is a native one, and there’s a large, nitrogen-fixing shrub, false indigo, which is being used as a trellis for perennial, edible beans which are not yet ready for prime-time. They need some breeding work. There’s great perennial beans in the tropics and even in warm, temperate, or Mediterranean climates, but here we still need some work to be done.

PALMER: I’d never heard of perennial beans but this one is hardly new. Eric has the scientific name.

Eric has dedicated his career to advancing carbon-capturing, agro-ecological practices in temperate food forests. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

TOENSMEIER: Phaseolus polystachios. That was actually cultivated historically by Native Americans throughout the east, and some Native folks definitely still definitely grow and use it today. The beans are pretty small. They’re maybe the size of a mung bean but people eat mung beans, and with some work it could really be developed into a very exciting new crop for this climate. And the shrub, as well, is one of the most widely used agro-forestry crops in China, even though it’s native here, and it’s used as pesticide, as fodder, and as an indigo dye, so it’s a very nice multipurpose species as well. It’s one of the best of our native species for agro-forestry.

PALMER: Well it’s interesting that you have beans because obviously beans are one of the three sisters - the corn, beans and the squashes - which the Native Americans grew, and they in fact grew the beans up their corn plants.

TOENSMEIER: And still do. We’re looking at a similar model. We’ve done some different trials here trying to replicate that particular corn, beans and squash with perennials, and we have not found the perfect match but this kind of system of a vine climbing on a nitrogen-fixing tree you see a lot throughout the tropics.

PALMER: This cohabitation is a recurring theme in Eric’s garden. It seems every crop has other plants with multiple uses growing around, above, and underneath.

TOENSMEIER: In these multi-strata systems, these food forest systems, we try and take advantage of all the space. So we ask ourselves, “What can we produce in the shade or in the partial shade beneath and between those trees?” In the tropics it’s things like coffee and cacao and vanilla or kava, tea, a lot of really wonderful crops. We don’t have anything quite that great here yet for really full shade, but we’re growing lots of perennial vegetables in the shade, culinary herbs, nitrogen-fixing plants, plants that attract beneficial insects, aggressive ground covers that serve as a living mulch.

A North American Paw Paw tree bearing fruit. (Photo Jerry Edmundson, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

PALMER: A living mulch that can stop erosion, be turned into the soil to add structure and attract soil organisms like worms, nematodes, and bacteria to break it down. I follow Eric around to a mostly shaded patch of yard space along the side of his house, where he’s growing fruit trees.

TOENSMEIER: These are paw paw trees, not the Caribbean paw paw which is papaya but the native, eastern paw paw of the U.S and, I think, a tiny bit of Southern Canada. It’s in the same family as a lot of tropical fruits like soursop or custard apple, but it really is very happy with the cold here. It’s native up into Michigan, so it can certainly handle cold. It produces a very large fruit. It’s North America’s largest native, edible fruit, I’m told, and I did see one last year that was the size of a large mango. Typically ours are more like a medium-sized potato. They’re still young right now, still small right now. And the really nice thing about paw paw is it’s very happy with partial shade, so it may be like our cacao or coffee in that it could be a shade crop for us in a commercial multi-strata system. In fact, the few commercial producers of paw paw that are working in the US now are finding that they are very vulnerable to wind damage and that inter-planting trees actually makes you ripen more paw paws because it slows down the winds.

Recording in Eric’s backyard space. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

PALMER: Beneath the paw paws is a pile of twigs and branches and suckers cut away from the trees. Instead of removing them, Eric often leaves this organic matter to decompose right there on the ground.

TOENSMEIER: As that material breaks down, it turns into organic matter, so a high residue system like this is very, very good for carbon, and we’re seeing that a lot around the world. Like in Brazil, there’s a very exciting agro-forestry movement underfoot that is largely based on heavily pruning timber trees to put carbon back into degraded soils, so we do a lot of that here, and it is unsightly to the average gardener and it was unsightly to me for many years but I’ve come to think, “Well if the ground in my garden looks like the soil of a forest, then I’m on the right track”.

PALMER: Eric leads me to the back of the garde, conveniently screened by a 12 foot bamboo grove whispering in the breeze. He uses bamboo for just about everything.

TOENSMEIER: This one we absolutely love. It’s just such a useful product for us to have in the garden for trellising, for staking things. Almost every challenge we have, we use bamboo. When our fruit branches are so heavy with fruit that they want to break, we cut some bamboo and put it on there to prop it up. So it’s listed as having about 1,500 uses. One of the challenges is that it often doesn’t fit into the climate finance system we have because it’s not properly a tree. It’s a giant grass so a lot of these fall between the cracks in national agencies because they’re maybe not really forestry and not really agriculture.

PALMER: How many different species are you growing here do you think?

TOENSMEIER: We’re growing about 300 species of useful perennials. Maybe 70 or 80 of those are woody plants, which would be trees or shrubs or bamboos. We have about 80 species with edible leaves, perennials with edible leaves, about 50 perennials with edible fruit, and then a whole diversity of other things, and then we grow a whole bunch of annuals too and different kinds of micro-livestock as well and some kinds of fungi that we cultivate. So it’s very diverse, and, although it’s a crazy level of diversity for a farm, for a very small garden, it’s fun if that’s what you’re into.

Bamboo has over 1,500 practical applications. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

PALMER: Over alongside the neighbor’s fence, Eric grows fruit bushes, some familiar, like raspberries, Asian pears, and blueberries, and some more unexpected...

TOENSEMIER: And if we turn and face the other way we have a young persimmon that’ll eventually fill in this area and then a chestnut and then a mulberry, so we’re really looking beyond the north edge of building out this very fruit and nut type forest. And we have some trees with edible leaves that we’re very excited about, and we’re starting to move those around the garden more and more as well.

Eric considers berries “the gateway drug to perennialization.” (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

PALMER: Trees with edible leaves...Now are you going to eat these?

TOENSMEIER: We eat them now! In fact the main problem is that we’re eating them so much so much that they’re not growing well enough, and we need to lay off of them for a little bit.

PALMER: Eric has calculated that his garden makes its own small but noble contribution to addressing the carbon crisis.

TOENSMEIER: We ran numbers at one point on our backyard and figured that the carbon sequestration happening here in this tenth of an acre offsets the emissions, roughly speaking, the emissions of one American adult in one year. So certainly the scale at which we’re doing this is not the scale which is necessary to fully address the problem, but it’s sort of a research and development project, and it’s certainly doing more than mowing a lawn. It’s a step in the right direction.

PALMER: Which direction should we step in now? Eric heads over to what he described as the carbon-sequestering food of the future.

TOENSMEIER: This is a bush clover that grows about nine or 10 feet high here. It’s a marvelous feed for livestock, it’s a commonly used agro forestry species in Asia, and you can make leaf protein concentrate out of it.

PALMER: Yes, Eric believes our children and grandchildren could be, and maybe should be, eating leaf-concentrate steaks. There’s a whole class of these grasses that you can extract protein from, and some yield a concentrate that’s as much as 50 percent protein on a dry-weight basis.

The practice of inter-planting crops is demonstrated by this patch in the Island of Pohnpei. (Scott Nelson, Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

TOENSMEIER: So by switching to these giant grasses you can produce protein and energy on the same land while sequestering carbon in the soil. So there are a lot of these very new, interesting things emerging, and the proposal is to feed that protein to livestock. I would argue you can also feed it to people, as someone who eats it myself. But the productivity on a per acre basis of protein with leaf protein concentrate is about 30 times more than beef. So there are a lot of interesting places we can go. I like beef! I think it’s delicious but...

PALMER: You don’t have hamburger every day.

TOENSMEIER I don’t have hamburger every day, and I don’t really think, unless maybe you live in Wyoming or Montana where grazing is the most appropriate use of the land, farming-wise in some places, I don’t think we’re all going to be eating three steaks a day, and that’s how we’re going to get climate change mitigation.

PALMER: But in spite of all the novel ways Eric’s trying to help, he admits that carbon agriculture has its problems.

TOENSMEIER: There’s a limit to how much carbon you can store in soil and biomass, and experts estimate that that’s somewhere around 200 billion tons globally. So, in other words a soil fills with organic matter to a certain point, and then it’s, they say, “saturated.” It’s more or less filled up, and a forest will rapidly sequester carbon when it’s young, but, when it starts to fill in, it’s full, and it’s not going to put it on at a very rapid rate anymore.

PALMER: That's, that’s actually a little daunting, the fact that we cannot sequester all the carbon we need to, to actually reduce the parts per million of CO2 to the 350, the famous 350.

TOENSMEIER: If we did it now and ceased all emissions today we could. So, given that all emissions are not going to stop this year, we need to look for more and more aggressive ways to sequester carbon on farms.

Digging arrowroots in a home garden in St. Martin. (Photo: Eric Toensmeier)

PALMER: How receptive are farmers in general to this kind of idea, to this kind of shift of the way they work?

TOENSMEIER: Well, in the United States a lot of our farmers are very grumpy about climate change and don’t think it’s a real thing at all, but, when you talk about the particular practices, many of them are very excited about them and want to do them. Certainly many of our farmers obviously both believe in climate change and are enthusiastic about trying to mitigate it on the farm, but not all of them are.

The barrier is that, to make a transition on your farm, even if you’re, let’s say, just changing from conventional to organic, let alone bringing in an agro-forestry system, is you’re looking at a two to five year period where you’re losing money, and most farmers are not operating in a way that they can do that. So that’s where the need for finance comes in, and we see all these people divesting from fossil fuels. We’d like to see a robust financing system, so they can invest that money in carbon farming. It goes out to farmers to make these transitions, to get over that two to five year hump, and it’s not like we need to pay farmers every year forever to do this. We just need to help them make the transition because again most of these practices increase production on the farm.

PALMER: Before I leave, I ask Eric if he has any advice for home gardeners like me who want to sequester more carbon in their patch.

TOENSMEIER: Well, the first thing is growing any of your own food at all is reducing emissions for transportation, and anything you can do to reduce tillage, to have a no-till system, a heavy mulch system, is going to be excellent. Any of your own composting you can do is going to be excellent; you’re starting to bank some of that carbon in your soil organic matter, and the more you can perennialize the better.

The Carbon Farming Solution offers all the details into this one branch of Permaculture. (Photo: Chelsea Green Publishing)

And I feel like the gateway drug to perennialization is berries. Everybody like berries. Berries are delicious. They’re really good for you. Most of them are pretty easy to grow, and in this climate we have some good options for at least partial shade and a few for full shade. And that’s where I would have people start.

PALMER: And that way they can be part of the carbon farming solution?

TOENSMEIER: Absolutely, absolutely. If all of us did this in our gardens it wouldn’t be enough to do the trick, but it would be a huge contribution.

PALMER: I’m sold, and not only because the bounty of Eric Toensmeier’s backyard is such an inspiration and a rebuke to less competent, more scattershot gardeners like me. It’s also because, if we believe the climate’s changing, and the way we live here in the more developed part of the world is making thing things worse, then working to fix the problem in whatever way we can is surely also our responsibility. And how wonderful that something as joyful and satisfying as growing your own food can be part of the answer. For Living On Earth, I’m Helen Palmer Holyoke, Massachusetts

Related links:

- The Carbon Farming Solution book

- Eric Toensmeier’s website about perennials

- Our first piece on Eric’s garden

[MUSIC: Henry “Red” Allen’s All Stars featuring Coleman Hawkins, “Let Me Miss You, Baby,” on Jazz Music For the Blues, Luis Russell/Red Allen, Madacy Entertainment Group of BMG]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Aidan Connelly Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Alex Metzger, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page, PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood.

Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth