June 9, 2017

Air Date: June 9, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Trump Moves to Drill in ANWR

View the page for this story

President Trump has moved to open up America’s biggest and wildest protected area, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge or ANWR, for oil drilling. Mr. Trump is also reviewing 27 National Monuments which are managed as national parks, to see if changes in size or status are necessary. Wilderness Society President, Jamie Williams, speaks with host Steve Curwood. (12:20)

BirdNote: The Arctic Coastal Plain

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

As Mary McCann explains in today’s BirdNote, each spring the Arctic Coastal Plain welcomes a vast abundance of birds from around the globe to mate and start a family. Nature photographer Gerrit Vyn describes the displays of male shorebirds, particularly the Pectoral Sandpiper, during mating season in the Arctic. (02:00)

Narco Deforestation

View the page for this story

Narcotics smuggling through Central America has led to the loss of as much as 1 million acres of forest over the past decade, as illegal cash from cocaine trafficking is sometimes laundered by clearing forests for cattle ranching and other legitimate ventures. Steve Sesnie, lead author of a new study that draws this connection, told host Steve Curwood how the drug economy is threatening some of the most remote, biodiverse forest in Central America and the people who have lived there for thousands of years. (09:35)

Primeval Forest Under Attack

View the page for this story

The Białowieża Forest in Poland and Belarus contains some of the last remaining old growth forest in Europe. Protections are strong in Belarus, but some areas in Poland are managed as commercial forest and the Polish government has now authorized a three-fold increase in logging. Living on Earth host Steve Curwood spoke with University of Warsaw Professor Bogdan Jaroszewicz - the director of a research station in the forest - about the ecology of Białowieża and what logging could mean for conservation efforts. (07:40)

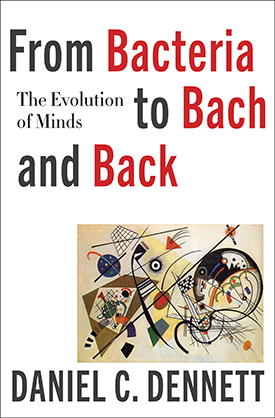

Minds, Machines and Evolution

View the page for this story

How machines learn is a growing branch of consciousness studies and one of the subjects addressed by analytic philosopher Daniel Dennett in his new book, “From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds.” Host Steve Curwood met Daniel Dennett at his Tufts University office where they discussed the origin of life, the evolution of language and why we should worry about our increasing dependence on the machines that have made modern life so convenient and simple. (15:50)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jamie Williams, Steve Sesnie, Bogdan Jaroszewicz, Daniel Dennett

REPORTER: Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. With Republicans in control, President Trump wants to drill in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

WILLIAMS: What you see is political opportunism by politicians who see this as a symbolic victory to turn our public lands over to the oil and gas industry. And the Arctic Refuge is the wildest, biggest place in the country. And if they can open this up to oil and gas drilling, then what park in America is safe?

CURWOOD: Also, how drug money drives deforestation in Central America...

SESNIE: There's a tremendous amount of profit to be made, especially as you move cocaine northward. So that leaves a lot of money in these spaces. So clearing forest for cattle, and those cattle can be sold, that allows that money to be legitimized or transferred into the legal economy.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Trump Moves to Drill in ANWR

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), shown above, represents the largest and wildest public in the United States. Proposals to allow oil leasing in the region have failed multiple times in the last several decades. (Photo: Alaska Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Republican-led Washington is looking to open up more of America’s public lands for development and fossil fuel extraction. President Trump has ordered a review of some 27 National Monuments protected over the last 30 years, including Grand Staircase Escalante in Utah, set aside by President Clinton and nearby Bear’s Ears, which was protected during the final weeks of the Obama Administration. June 10th is the deadline for Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke to send his recommendations to Mr. Trump. Also through his proposed budget, President Trump has signaled he wants to open up the iconic Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, in the far North Slope of Alaska, to oil and gas drilling, reigniting a controversy that has enflamed passions since 1977.

We’re joined now by Jamie Williams, the President of the Wilderness Society, to discuss the refuge and the potential threats to other protected natural areas. Welcome to Living on Earth, Jamie.

The National Petroleum Reserve is another federally-owned area with similar ecology near the ANWR. State and federal lawmakers have shown less interest in the region’s oil stores than in its more contested neighbor. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

WILLIAMS: Thank you. It’s great to be here.

CURWOOD: So, let's start off by having you describe the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Many people call it by its initials ANWR. Why is it important?

WILLIAMS: Well, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is the largest wildest place in all America. It's in northeastern Alaska, from the Brooks Range and descends down through the coastal plain to the Arctic Ocean, and it's truly America's Serengeti. The coastal plain is the biological heart of this amazing place where every June it explodes with life, where more than 180,000 caribou migrate every year to rear their young, where hundreds of birds species come, as well, to rear their young, and then migrate to every state in America and all over the world, and also where polar bears and many other wildlife depend on for their survival. So, it is a really important wild place for America and it's also really important to local native Alaskans who depend on caribou in particular for their food and for their culture, and so it's no accident that they call the coastal plain the sacred place where life begins.

CURWOOD: So, the president has put this in his budget. The budget is unlikely to go very far, given the present politics in Washington, but he sent the signal that he would like to open up the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil and gas drilling. What would need happen exactly, though, for drilling there to become a real possibility?

The Gwich’in Nation, whose flag is above, is indigenous to Northern Canada and Alaska. The Gwich’in refer to the coastal plain of ANWR as “the sacred place where life begins”. (Photo: Xasartha, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

WILLIAMS: Well, like any park or protected public lands to open it up for drilling or development would require an Act of Congress, so that is essentially what President Trump is proposing by putting it in his budget to be taken to Congress, and we know that there are members in Congress who would like to see this happen as well. Senator Murkowski from the state of Alaska has introduced legislation that would also open up the refuge to drilling. So, in the 37 years that this refuge has been set up and protected, this is the most serious threat we've ever faced to opening it up for oil and gas drilling.

More importantly, we know that the majority of Americans do not want to see the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge developed. It's why this kind of proposal has been defeated in Congress multiple times over the past 37 years and why we believe it can be this time, but only if people really stand up and let their elected leaders know that they don't want to see America's wildest place drilled for the very last drop of oil at a time where there's plenty of oil in other places, and this is the most expensive place to drill.

CURWOOD: Now, next to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is similar land, but it's called the National Petroleum Reserve. Why isn't the the oil industry interested in doing extraction from there and pushing for opening up the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge?

Caribou and their migrations are critical to ANWR’s ecosystems and to the livelihoods of indigenous communities in the area. Oil drilling could interfere with caribou migratory patterns and cause irreparable harm to the region, says The Wilderness Society’s Jamie Williams. (Photo: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

WILLIAMS: Well, that's a very good question because this is really not about where the oil companies want to drill right now because it doesn't make economic sense to be drilling in the Arctic. It's about an ideological battle that's being waged by politicians that would like to open up our public lands to unfettered oil and gas development. One thing to recognize here is that over two-thirds of existing leases on our public lands that are held by oil companies are sitting idle and are not being drilled. That's more than 6,000 leases throughout the country that are not being utilized right now because the economics aren't there. What you see is political opportunism by politicians who see this as a symbolic victory to turn our public lands over to the oil and gas industry and the Arctic Refuge is the most symbolic of them all. It's the wildest biggest place in the country, and if they can open this up to oil and gas drilling, then what park in America is safe?

CURWOOD: Now, talk to me about what happened the last time that there was legislation in front of the Congress on opening the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, ANWR.

WILLIAMS: Well, there was legislation in 2005 was the last time that we saw this battle which was defeated, and the reason was the American people spoke up across the country, as they have time and again, that they don't want to see their natural and cultural heritage compromised for industrial development particularly in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

The distant spires of Monument Valley, as seen from the Valley of the Gods in Utah’s Bears Ears National Monument, currently under review by the Trump Administration. (Photo: John Fowler, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, what's different over the question of drilling in the Arctic this time around, and why do proponents of this think that perhaps they have a chance?

WILLIAMS: Well, I think that proponents think that they have a chance this time because you have the alignment of extreme interest in the House with members of the Senate and now with the Trump administration, in trying to open up our public lands for unfettered oil and gas development. So, that political alignment between the three branches of government is I believe why they see that there's an opportunity. We still believe that politicians across the country will continue to hear from their constituents who care about this place and that they will stand up and do the right thing, but that will only happen if Americans recognize the threat we truly face and if they stand up and let their members know how much they care.

CURWOOD: Let's switch gears a bit here and talk about the National Monuments. The Trump administration is reviewing some National Monuments. There are a lot. Maybe you could mention just a few of particular concern.

WILLIAMS: Well, this is the first time in history that a president has proposed revoking or shrinking a National Monument. More than 150 have been established by presidents on both sides of the aisle that protect our natural and cultural heritage and tell America's story, and now we have an administration and a president who has called for the review of every National Monument established since 1996, more than 54 of them. So, they are looking from the Katahdin Woods and Waters in Maine to the Bears Ears National Monument in Utah to the California desert to the Cascades in Oregon, and many, many more.

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah was designated by President Clinton in 1996, and is also under review. (Photo: Bob Wick / Bureau of Land Management, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And, Jamie, remind us of some areas that started as National Monuments that we now see as National Parks.

WILLIAMS: So, Acadia National Park started as a National Monument. The Grand Canyon was the first big National Monument established by Teddy Roosevelt in 1908. The Olympic National Park in Washington was also started as a National Monument. More than half of our National Parks started as National Monuments. This is essentially a first step to making a National Park is National Monument status.

CURWOOD: So, what does the law say about revoking a National Monument once it's been declared?

WILLIAMS: The Antiquities Act, which was passed by Teddy Roosevelt and Congress in 1906, gives the president the express authority to create a National Monument, to protect important places of natural, cultural, scientific, and historic qualities, but it does not give the president the authority to revoke a National Monument. Congress, of course, can do that, but the Antiquities Act does not give the president the authority to do that.

CURWOOD: Let's say that, for whatever reason, President Trump does say he wants to revoke one of these National Monuments. What would happen?

Sand to Snow National Monument, east of Los Angeles in California, is another of those under review by the Trump Administration. President Obama designated its 154,000 acres a National Monument in February 2016. (Photo: Bob Wick / Bureau of Land Management, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

WILLIAMS: Well, if the President we're to step forward and withdraw the protection of a National Monument with executive authority, I think what you will find is, they will go to the courts and that'll take many years to settle out.

CURWOOD: And let's just say at the end of the day that President Trump decides to revoke one of these National Monuments, it makes its way to the courts, and the courts finally say, “Well you can do it.” What would it mean for those areas if that status was revoked?

WILLIAMS: Well, what it would mean...it would mean losing the protections for these very special landscapes, landscapes that we love to go, to renew our spirit and soul, and in particular, in the case of Bears Ears in Utah, this is a sacred place to five tribes came together and actually proposed the creation of this National Monument. And what you're seeing right now is rock art, beautiful rock art that's tens of thousands of years old being shot off with guns, grave robbing of sacred sites and looting of a tremendous number of archaeological sites that exist throughout the Bears Ears region. So, without the protection, this kind of vandalism and looting will continue to proceed as it is now, which is really why the Antiquities Act was established in the first place.

CURWOOD: Now, proponents of looking again at these National Monuments, some of them think that the states should have more rights over this public land rather than the federal government. What's your response to that argument that the states should have more control of the land that they're part of?

WILLIAMS: Well, I think that there's a bigger agenda going on here, which is to transfer national lands that are owned by all Americans to the states so that they can be sold off to the highest bidder. If you look at Utah in particular, more than half of the lands that have already been transferred from the federal government to the state have been sold off.

Jamie Williams is president of the Wilderness Society. (Photo: Jamie Williams)

The states can't afford to manage all of these lands, to handle the cost of firefighting, let alone all the other costs, and the great thing about a National Monument is it provides a mechanism to protect these places for future generations but it also involves a development of a management plan. So, in Bear's Ears in Utah, for example, traditional uses of grazing and hunting will continue. The Native Americans who collect firewood and collect herbs there, things like that, those kinds of traditional uses will be allowed to continue while the resources of that incredible place are protected.

CURWOOD: Jamie, much of the federal land in the west was taken from Native Americans, and we don't have to go into that bloody and unfortunate history. But to what extent do the National Monuments take a step towards reparation to America's Native American community?

WILLIAMS: Well, Bears Ears is a really important step towards righting the wrongs that this country has inflicted upon the First Americans and the Native Americans of this country because it not only protects a place that five local tribes asked to be protected, that has huge importance to them, but in the proclamation it gives those tribes a seat at the table in the management of that monument going forward, and really sets a better precedent for recognizing tribes for the sovereign nations that they are and giving them an equal seat at the table with the US government in how these kinds of places that have such important historic significance to these tribes will be managed in the future.

CURWOOD: Jamie Williams is President of the Wilderness Society. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today, Jamie.

WILLIAMS: Thank you, Steve. I really appreciate it.

Related links:

- CNN Money: “Trump wants to drill for oil in Alaska’s fragile wildlife refuge”

- LA Times: “Here are the national monuments being reviewed under Trump's order”

- Outside Magazine: “What Trump's Proposed Budget Means for Our Public Lands”

- The Wilderness Society

- The National Wildlife Refuges

- Explore the Bears Ears National Monument - from your computer

BirdNote: The Arctic Coastal Plain

The male Pectoral Sandpiper displays its pectoral sac, as shown above, before embarking on its territorial, mating flight. (Photo: Gerrit Vyn)

[MUSIC: BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: Well, as Jamie Williams was saying, Alaska offers an extraordinary bounty of wild creatures for anyone who visits to see, and as Mary McCann explains in today’s Birdnote®, that’s especially true at this time of year.

http://birdnote.org/show/arctic-plain-june

BirdNote®

The Arctic Coastal Plain in June

[Spring bird song on the Arctic Plain recorded by Gerrit Vyn]

MCCANN: In early June, millions of birds arrive on the Arctic Coastal Plain in Alaska, from all over the world. They’re there to attract a mate and raise their young. They’ll feed on the explosion of insect life that happens in the brief spring. Nature photographer (and sound recordist), Gerrit Vyn, takes us there:

VYN: So, when the shorebirds arrive, it’s an absolutely spectacular event. Soon as they get up there, these male shorebirds of all different types begin all of these unique displays –

If you go up there on a calm, still, spring evening when the winds subside, all of these birds just lift off the ground and the tundra can appear barren and within a few hours you just hear thousands of birds in every direction calling and singing…

There’s one shorebird species, the Pectoral Sandpiper, where the male has this pectoral sac at its chest that...It’ll stand on the ground for awhile and inflate this sac and then take off on these sort of moth-like, buoyant flights low over the tundra, emitting this incredibly resonant, hooting song as it’s circling its territory, trying to chase off other males and attract a female…

A Pectoral Sandpiper takes flight. (Photo: Gregg Thompson)

[Flight display song of the Pectoral Sandpiper from LNS#130964]

It’s a really incredible thing to see this bird floating toward you uttering this loud resonant hooting sound.

[Flight display song of the Pectoral Sandpiper from LNS#130964]

I’m Mary McCann.

###

Interview of Gerrit Vyn by Chris Peterson

Songs and calls of the birds at the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, recorded by M.J. Anderson and Gerrit Vyn. Feature of Pectoral Sandpiper by Gerrit Vyn LMS 130964.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2013-2017 Tune In to Nature.org June 2017 Narrator: Mary McCann

http://birdnote.org/show/arctic-plain-june

CURWOOD: For photos, soar on over to our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Listen on the BirdNote website

- More information on the Pectoral Sandpiper

Coming up, a fight to save one of the oldest forests of the Old World. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joel McDermott, “Concerning Balloons and Birds” on Wire Work, Catapult Records https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9egA-5b-xNM&index=8&list=PL0ugPX0ggLBJ64pVxyTsZDOAvLBPfhaWb]

Narco Deforestation

Deforestation in northern Honduras (Photo: John Donaghy, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. The illegal drug trade from South America generates huge, illicit profits for the traffickers, and now research by the US Fish and Wildlife Service has found that laundering those profits drives a good deal of deforestation along the smuggling routes in Central America. It appears the drug profits are being used in many cases to purchase land deep in the forest for cattle ranching. The beef can then be sold legally with proceeds that can be explained to bankers. And that has led to the destruction of some one million acres of Central American forest over the last decade, according to a team led by ecologist Steve Sesnie of the US Fish and Wildlife Service. He is the lead author of a new paper in Environmental Research Letters that documents this “narco-deforestation” effect.

Steve, welcome to Living on Earth.

SESNIE: Hey, thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So, where are we talking about? Where was your research conducted?

SESNIE: Well, it was across all of Central America, looking at each country independently, but we focused more narrowly on a few countries where we were seeing higher rates of deforestation, larger patches of forest being cleared, and that naturally led to these areas with higher volumes of cocaine trafficking occurring, and that's mainly in the northern triangle. Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, were the main countries that we eventually ended up focusing on.

CURWOOD: So, this is very interesting. How much cocaine production is there in those countries?

U.S. Navy sailors stack up 525 bales of cocaine seized during an interdiction off the coast of Central America in 2004. (Photo: Eric Weber / U.S. Navy, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

SESNIE: Very little actually. Most of production occurs in Peru, Bolivia, and Columbia, and this is a trafficking area where cocaine is being transported northward towards that the US border. Eighty-six percent of the cocaine that arrives in the US is transported through Central America currently.

CURWOOD: So, why is it that people who aren't growing cocaine...There doesn't seem to an agricultural need, but why is there so much deforestation where this stuff is being transported through?

SESNIE: That's a really interesting question. They seem to be unrelated, but in fact there’s a tremendous amount of profit to be made especially as you move cocaine northward. So that leaves a lot of money in these spaces, and money is often invested in other illegal activities or illegal land markets. So, clearing forests for cattle, and those cattle can be sold or land could be resold, that eventually allows that money to be legitimized or transferred into the legal economy. So, that's kind of the nexus of where the deforestation comes in. It's an agricultural driver, but underneath it is trying to launder these illegal profits.

Cattle being driven along a rural road in Honduras (Photo: Frank McGrath, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, how did you come up with that one million acre figure? What tools did you use?

SESNIE: It was a release of a global forest change data set. Some geographers at the University of Maryland had developed a way to, in the Google cloud, process millions of satellite images in a way that would develop annual estimates of forest loss and gain all around the globe. And so, that's some data that we’ve just never had before, allowing us to look at what might be considered background or "business as usual" deforestation for typical land settlement and agriculture which has been happening for many decades in Central America to this anomalous -- is what we're calling it -- very different form of land clearing. It's not very easy to clear and maintain tropical forest, so a lot of resources must be invested in order to do that, Chainsaws, gas, many individuals working together. And so we were seeing patches, sometimes over 100 hectares cleared in these very remote spaces at a very rapid pace, and that was what we are calling anomalous or a very different signature of forest loss.

CURWOOD: Or narco-deforestation.

SESNIE: Narco-deforestation. So, all of that came together when we started to combine this information and with the consolidated counter narcotics database, which is a database that quantifies, number one, how much cocaine per year is being transported to certain countries, and that's detected by radar and other monitoring devices, and then the amount of drugs that are seized or lost or delivered, and all that's quantified by the Office of National Drug Control Policy and kept as a record for each year. So we were able to combine this forest loss data with the flow of drugs at the country scale and also below the country scale within certain departments, and we found some strong correlations between two.

The coca plant is grown in South America for traditional uses as well as processing into cocaine that finds its way all over the world. (Photo: echo.plexus, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, where are the narco funds being laundered in this way, and what kind of ecology are we looking at? How important are these places biologically and culturally?

SESNIE: So, these are very remote spaces mainly along the Caribbean coast of Central America. So these are really the last large expanses of lowland, highly diverse, tropical forests that are also inhabited by several indigenous groups that are primarily the stewards of those areas. They are fishermen. They are hunters. They are small-share farmers that have lived in these faces for many thousands of years, and often times they engage in land clearing, but it has been traditionally this shifting cultivation where small areas are cleared and then left to rest. In tropical forest settings, things can recover quite quickly.

CURWOOD: What's going on, then, with those indigenous communities that are seeing the forest being cleared by folks who are flush with money from the narco trafficking?

SESNIE: Well, it's an interesting relationship, and it's not all always a bad one. Often, the traffickers themselves, they may actually provide some sources of employment that weren't there before. Some have been known to provide health benefits. Some support community activities, so oftentimes the traffickers may be fulfilling an economic development role, but that can also bring a great deal of violence. Murder rates in these areas have risen sharply. It can bring a lot of social health problems with it, so, as these drugs flow through these remote areas, they're also consumed. So, it's really a double-edged sword, but I think more often than not through the lifecycle of, say, a trafficking node or a trafficking center, there can be a great deal of harm and violence that also are currently in these spaces.

Honduras, Guatemala, and Nicaragua – the countries Sesnie’s team focused on in the study – are among the poorer countries in the world. Lucrative cocaine trafficking operations in these countries can bring rare prosperity to some of the most remote and undeveloped corners of these countries, but they can also bring violence. (Photo: ONE DROP, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, of course, your research focused on the use of these illegally gained funds to contribute to deforestation, but I imagine that not all the illegal money from the narco trafficking in that region goes just into the deforestation. To what extent do you see luxury hotels appearing in places that might otherwise not be funded?

SESNIE: That's an astute observation. Money is being invested, and it's very opportunistic. Things like tourism, hotels, you name it, any sort of infrastructure, African palm plantations, other forms of agriculture. I've heard of shade-grown coffee, a whole wide variety of places where money can be invested and turned into legal profits, but the source often starts out as profits gained through trafficking.

CURWOOD: Now, why is Central America such a big transit zone for cocaine these days?

SESNIE: As you may know, the drug war often has a shifting front and during the 90s the Caribbean islands - Jamaica, Puerto Rico - were key trafficking hubs on their way to states like Florida, and the interdiction pressure put on the traffickers in that space really forced them over. It shifted over to Central America in the early 2000s, and it's a much larger landscape in Central America than these small islands. Many, many more places to conceal activities. It has become a regional activity that's in constant motion, constant adaptation.

CURWOOD: Steve, what can be done, if anything, to combat this narco-deforestation?

SESNIE: Well, I think it is very much a multipronged approach that is needed and not necessarily an escalation of the interdiction, but some social education, rural development. All of those, I think, are important policy mechanisms or parts of foreign aid that might improve the situation in Central America. These are just as important, if not more important, than the interdiction.

CURWOOD: Steven Sesnie is a Spatial Ecologist with the US Fish and Wildlife service and lead author of an article about narco-deforestation in a recent issue of Environmental Research Letters. Steve, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

SESNIE: Yeah, thanks for having me. I really appreciate it.

Related links:

- Read the Narco Deforestation study: “A spatio-temporal analysis of forest loss related to cocaine trafficking in Central America”

- The Guardian: “‘Narco-deforestation’: cocaine trade destroying swaths of Central America”

- InSight Crime: “US Report Shows Revitalized Central America Cocaine Corridor”

Primeval Forest Under Attack

The Białowieża Forest is the largest vestige of primeval forest in lowland Europe. (Photo: Eric de Haan, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Environmental activists in Poland are chaining themselves to logging machines in an ancient forest to protect the trees from being cut down, which they, say violates EU conservation rules. The Białowieża Forest is a UNESCO World Heritage site that straddles the border of Poland and Belarus. It’s perhaps the largest remaining primeval forest in Europe, and most of it is in Belarus where it is fully protected. But in Poland about two-thirds is managed as commercial fores, and the government has recently tripled the amount of logging allowed there, claiming it will combat an attack of the Spruce Bark beetle. Yet Professor Bogdan Jaroszewicz, who directs the University of Warsaw’s Geobotanical station in the forest, says the beetle is part of a natural cycle, and logging is only making things worse.

He joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

JAROSZEWICZ: Nice to be here.

CURWOOD: So, how old is this forest and why are people concerned about it being preserved?

JAROSZEWICZ: The forest itself has 10,000 years of continuity. So, when the last glaciation withdraw from here, the area was colonized by trees. The forest ecosystem developed, and that was the beginning of this forest. And the conflict in Białowieża Forest is about extension of the logging rate in one of the districts which are managing Białowieża Forest. And one year ago in April 2016, our Minister of Environment, Jan Szyszko, increased threefold logging rate in the Białowieża Forest district. That's one of the three districts which manage Białowieża Forest.

CURWOOD: Now, which parts of the forest are protected as a nature reserve, and which parts are open to logging?

JAROSZEWICZ: On Polish side, which covers 62,000 hectares, about 36 percent is protected. The rest is managed by foresters as commercial forests.

CURWOOD: So, if I were to go into this forests, what kind of creatures and nature would I find that is tough to find elsewhere?

JAROSZEWICZ: The most iconic species is the European bison. That's a species which was extinct in wild at the beginning of the 20th century and then was reintroduced to the Białowieża Forest in 1952 and from here it was then arranged for these two other forests or other places in Europe. The Białowieża Forest is also the only place, at least in Poland, where we have Laxmann's shrew, so the special type of the shrew which has an Eastern type of distribution in Eurasia, so further west of Europe it's quite rare.

The Białowieża forest is home to many Bison, Europe's heaviest land mammal. (Photo: wer mei, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

There are also several woodpecker species in many European countries extinct long time ago, like White-Backed woodpecker or Three-toed woodpecker. So those two woodpeckers are associated with dead wood and dying trees, and that's why they are extinct in the other countries and in Białowieża Forest they are in very good shape.

CURWOOD: What's the reason? What are the justifications that the Polish government gives at this point for the increased level of logging in this primeval forest?

JAROSZEWICZ: So, the main justification is that they have to fight with the Spuce Bark beetle outbreak, and that's the main message which they send, that without cutting of dying and dead spruces, the whole forest is going to die. In effect, the government, the Minister of Environment and forest service are say that they are trying to protect European Natura 2000 habitats and species, and they are trying to restore habitats that are degrading because of the Spruce Bark beetle outbreak.

CURWOOD: How credible is this argument of the government, do you think?

JAROSZEWICZ: Well, it is, let's say, credible from the point of your commercial forestry, but they're using to justify economic aims by ecological reasoning. I mean, they are cutting spruces to sell the wood. From ecological point of view it brings rather just damages, and our experience here in the Białowieża Forest shows that it doesn't matter if infested spruces are logged or not. The outbreak stops after some years.

Bogdan Jaroszewicz is the director of the University of Warsaw Geobotanical Station in the Białowieża forest. (Photo: Bogdan Jaroszewicz)

CURWOOD: So, as I understand it, there's some evidence that the rate of logging that is going on now in this forest is against the regulations of the EU. So, tell me, what efforts has the European Union made so far to challenge the actions of the Polish Environmental Ministry about this?

JAROSZEWICZ: So, last year European Commission sent a special mission to Białowieża Forest to check on the ground what is the effect of logging on habitats and species which are protected by Natura 2000 network of protected areas. And then, they asked Minister of the Environment for justification and an explanation of this increased logging rate. As far as I know, our Ministry answered this letter from the European Commission, but logging was not stopped or limited. European Commission may accept the situation or may send the case to European Court of Justice, and that means that then we'll have a problem as a state.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about your research at your geobotanical station there. What are you doing now, and how, if at all, are your studies going to be affected by this increase in logging?

JAROSZEWICZ: So, our station's let's say speciality are the so-called long-term studies. We have several projects which run for 50 or over 50 years. We are also studying biodiversity of plants, bryophytes, and lichens, how forest is reacting on changing environmental conditions, and that's generally in core area of the national park, so logging doesn't impact this part of our research. But we have also several projects which are carried in the commercial part of the forest, and there we for example, have lost several permanent plots due to logging. Simply, when the forest was logged, the whole plot was damaged and we are not able to reestablish it. So, we are losing part of our data and part of our projects, and that's the main problem.

CURWOOD: Bogdan Jaroszewicz is a biology professor at the University of Warsaw and the director of the Geobotanical Station in Białowieża Forest. I want to thank you for taking this time with me today.

JAROSZEWICZ: It was a pleasure.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Białowieża Forest

- Geobotanical Station in Białowieża

- Białowieża is a UNESCO Heritage Site

- Phys.org: The EU may step in and enforce logging limits

[MUSIC: Childsplay, “Mothers Of the Disappeared/The Evenstar” on Waiting for the Dawn, composed/arranged by Hanneke Cassel, Childsplay Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up...how evolution has worked to connect our neurons into networks that think. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward.

This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Robin Adnan Anders, “Desert Wind” on Omaiyo, Rykodisc Records]

Minds, Machines and Evolution

The pruning process of evolution favors some patterns and disfavors others, says Dennett, and this has enabled life to evolve from single-celled bacteria (somewhat like the dividing cells above) to the complex array of life on Earth today. (Photo: NIAID, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

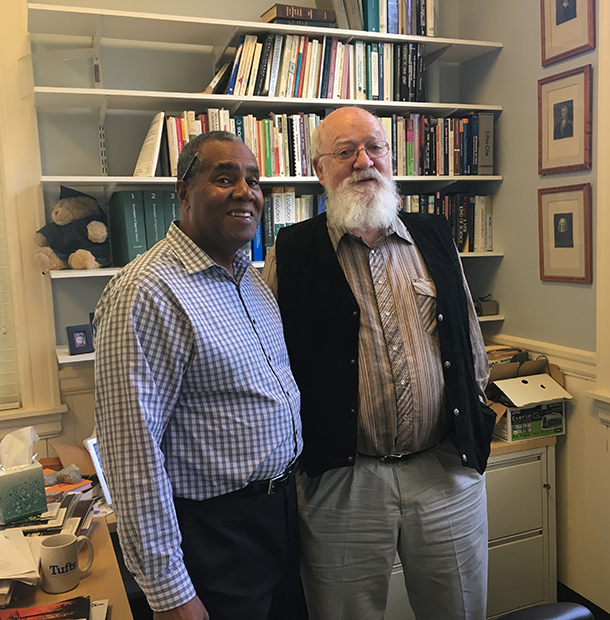

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. The analytic philosopher Daniel Dennett almost always seems to be thinking about the nature of consciousness, unless he’s writing about it, as in his newest book, “From Bacteria to Bach and Back”. The Tufts University professor has an enormous, white beard and a twinkle behind his spectacles, that makes him, well, rather look like Santa Claus, that is, if Santa Claus were a deep thinker who’d written a dozen books and spoke with a gently authoritative voice inflected by playful curiosity.

Professor Dennett looks to nature itself to help explain consciousness in a seemingly unconscious universe, peering through lenses that range from evolutionary biology to cognitive science and at analogs to nature such as artificial intelligence and computer learning. Daniel Dennett co-directs the Center for Cognitive Studies at Tufts University, where we spoke in his office. From the start it was obvious that even the simplest of questions, such as the usual public radio query that we pose to set recording levels for interviewees, “What did you have for breakfast?” could launch us into profound philosophical debate.

CURWOOD: Yes so what did you have for breakfast?

DENNETT: I had scrambled eggs this morning.

CURWOOD: Yeah, and where did the eggs come from?

DENNETT: Er, hens.

CURWOOD: And where did the hens come from?

DENNETT: Eggs.

CURWOOD: And the eggs came from?

DENNETT: Hens and so forth, but not ad infinitum.

CURWOOD: Oh, all right. So, where does it begin?

DENNETT: It begins with pre-genetic evolution of molecules. It begins with great whirling cycles of pre-biotic phenomena, and when you have hundreds of cycles at different revolutionary speeds, if you like, things gradually sort themselves out, just the way the sand and the pebbles do on a beach when the waves are coming in. It isn't just confetti, there's a pattern, and, as the pattern grows, some patterns are favored and other patterns are disfavored, and after a while, something happens which permits a different kind of periodicity which is, in the beginning, it's hard to say that it is reproduction when we think about what the first living thing or first reproducing thing was.

Daniel Dennett's new book is an accumulation of his life's work on human consciousness. The book covers, in part, the origin of life, memetic evolution and machine learning. (Photo: courtesy of W.W Norton and Company, Inc.)

We tend to think about of some really simple bacteria, and I think that's almost certainly wrong. I think the first reproducing thing may have taken a thousand years to reproduce, but it reproduced. And gradually those early klugey Rube Goldberg reproducers got stream-lined. They had to because they were competing with each other. So, the stripped down, reproducing entity, that wasn't the origin of life. The origin of life was much earlier.

CURWOOD: Oh, OK. So, I know this is tough for a university professor, but give me the 30 second version of how, in your view, we evolved from microbes to the mind, or as you say your book, from bacteria to Bach.

DENNETT: Two processes had to happen. The first we all know about. It's Darwinian genetic evolution which created reptiles and then therapsids and then mammals and then primates along with all the trees and flowers and fish and all the rest of it. And something not miraculous, but something pretty unusual, happened, and there's a great debate about that, but, whatever happened, it gave birth to language, and language changed everything because language, like DNA, is digitized. We have phonemes which are like the ACGT of DNA, one of nature's great inventions. No person invented it, but once you have phonemes, you can transmit hi-fidelity information from place to place. Our ancestors from over thousands of years, maybe hundreds of thousands of years, they came to understand what it was, "Hey, we're talking", and it turns out that talking is just the most potent transmitter of information yet.

CURWOOD: Indeed, as we know on the radio right?

DENNETT: Absolutely. The great thing about talking is that you can learn things that your parents don't know. Genetically, we can inherit a lot of know-how, a lot of instincts, a lot of talents, the ability to digest our food, and to walk and all kinds of things are actually passed on through the genome pretty much the way a bird's ability to build a nest is passed on. They don't have to have seen a nest built to know how to build a nest. That goes on through the genes, but we, and we only, have this other information highway primarily made of language which makes it possible for us to learn from people that aren't related to us at all, from Socrates and Plato and to Galileo and from people living on the other side of the globe today, we have all of these sources of information, and what it does is, it multiplies by many orders of magnitude the ability of an individual organism to take on new competence and new comprehension.

Some philosophers of consciousness follow a tradition of dualism, introduced by 17th century philosopher René Descartes when he argued that the mind isn’t the brain. Daniel Dennett disagrees and says the human mind is a product of thousands of years of evolution by natural selection, which was aided by thinking tools called memes. (Photo: Laura Dahl, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, you say that there are two important figures that got you to this notion of evolutionary thinking. How did they change things?

DENNETT: Well, my two real heroes here are two Brits, Charles Darwin, and a hundred years later or so, Alan Turing. And their revolutions were actually similar. They're two faces of the same coin. What Darwin showed, as one of his early critics said, is that absolute ignorance can take the place of intelligence in the creation of all the wonders of the biosphere. The process of natural selection isn't the mind. It isn't intelligent. It's just a brute, mechanical algorithmic process that churns away mindlessly over the millions and millions of years, billions of years, and creates the bird's wing and the legs of the cheetah and all of the rest of the wonders of the natural world.

Turing had a very similar message. In his day, a computer was a person, typically a woman, who sat and computed, and he realized that the jobs they were doing didn’t require comprehension. You didn't have to have a degree in mathematics to do them. You could be entirely mechanized, and so he created the idea of an automatic mechanical mindless computer, and he described their smallest parts, bits, binary digits, zero or one, and a few basic operations, plus and minus and compared to zero, and you can get what's called conditional branching, and you're off to the races, and you get compute anything computable. So, again, what he was showing was you can have competence without comprehension, and he went on to say what comprehension is, in effect, is just layers and layers and layers and layers of competence that build on each other.

And here's where the Darwinian idea of gradualism comes in. There's no moment when a bell rings, and -- ta-da! -- we have comprehension. The model for comprehension is spending 12 years in school and coming out, not just competent, but being able to explain what the competence consists in, not perfectly but pretty well.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about competence without comprehension. In your book, you write about an interesting example, and that's the termite mound, and, you know, it looks remarkably like big castles, a place in Barcelona you point out that it could look like. Why this is comparison important, do you think?

DENNETT: Well, here we have two artifacts, the famous church of church of Gaudi, La Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, and the termite castle, and they look almost identical and, in fact, there's many structural details in common too. So, here we have two artifacts made by living things. They profoundly different in the research and development and building that went into them.

The termite castle is built by clueless termites, there's no architect, there's no leader. They just go out there and they do their little mindless thing and lo, and behold, this amazing structure appears. That's Darwinian research and development, competence without comprehension.

Gaudi's church, on the other hand, is a brilliant example of a charismatic genius autocratic work. He writes manifestos. He has the blueprints. He's ordering his subordinates around who order their subordinates around. This is top-down intelligent design, xmall "i", small "d". So, if we think of Gaudi as a sort of model of an intelligent designer and the termites as a model of an uncomprehending builder, then we have a profound gap between them. So, the question is, how do you get to Gaudi from the termite? How do you get to Bach from the bacterium?

CURWOOD: Yes, tell me.

Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood (left) joined Daniel Dennett at his office at Tufts University. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

DENNETT: And what particularly puts a point on this is, if you think about our brains, what we have between our ears is by latest count about 86 billion neurons, and each one of those is clueless. I mean, two million termites can make a castle, but they can't do it Gaudi's way. But you put 86 billion neurons in a brain, and, under the right conditions, you get science. You get art. You get politics. You get human culture, and the answer, I think, is and has to be by a second evolutionary process just as non-miraculous as the first, and that's cultural evolution. Once we have language, it starts out with our first speakers about as clueless as chimpanzees, let's say. Chimpanzees have maybe a dozen things that they can pass on to their young without going through the genes. We have hundreds and hundreds of thousands of things that we can pass on because our culture is cumulative.

CURWOOD: So, you're saying that language itself evolved on a track that is parallel to life itself by natural selection. How does that work?

DENNETT: Let's take words. Words have lineages. The word “table” comes from the Latin word “tabula”, which has earlier roots. So, if you think of a word as not alive but as subject to natural selection, words are competing for space in people's brains, and words go extinct. Words mutate. They change their meaning, their pronunciation.

Now, Darwin noticed this, and Richard Dawkins made a big thing of this in his book "The Selfish Gene", and he coined the term “meme”, which is more general than just words. There are ways of doing things like wearing your baseball cap backwards or dancing the foxtrot or kneading your bread just so and making an arch. Those things can be passed on non-genetically, and they evolve, accumulating mutations as they go, but you have to recognize that words and other memes, they have their own fitness, and that's key because we want to be able to explain all of human culture, not just the good stuff. There's junk and ugly practices, just bad habits. The point is, bad habits can evolve just as good habits do. Why? Because they're just more infectious. They grab onto some weakness in our makeup, in our dispositions, and they exploit it, just like viruses.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about the human mind and the machines, the computers, and what do you see is the next step in machine learning?

DENNETT: Modern day human beings are wonderfully intelligent designers, engineers, scientists, poets, artists, composers, but one thing we've learned, thanks to Darwin and Turing and others, is that evolution is cleverer than we are. So, now we're learning how to harness evolutionary and quasi-evolutionary processes to do the heavy lifting for us. So, we're creating a world in which we have these new oracle boxes that give us answers to our questions. Unlike the oracles of ancient times, we have very, very good reasons to believe what they tell us most of the time. But we can't understand exactly how we get their results, and that's a bit scary.

Daniel Dennett is the Co-Director of the Center for Cognitive Studies at Tufts University. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

CURWOOD: So, you're talking about the risks of becoming so dependent on our technology.

DENNETT: Absolutely. We have becoming breathtakingly dependent on technology that only a few of us know how to understand or repair. It used to be that, if your car broke down and you were a clever person, and had taken a few courses in automotive mechanics, you could fix your car. That day is disappearing fast. Now, of course, we're also losing our talent to read maps because GPS is taking over, and the fact is that if we were to have an electronic blackout, we would be thrust into the most destructive panic you can imagine. Of course, it would mean we would be suddenly thrust back into the 19th century. Well, life was pretty good in the 19th century. You could stay alive and comfortable and read books and have food and shelter and all the rest. We could in principle go back to that, but only if we anticipate that we might have to and think about who is going to know how to shoe a horse and who's going know how to make a steam engine that you fire up with firewood or something like that. Some people pride themselves in their sort of practical knowledge of the 19th century ways. They might be very important to us if we ever have that technological crash, which I think is distinctly possible.

CURWOOD: Some people worry that, as computers advance, as artificial intelligence advances, that the machines will take over. How much of that concern do you share?

DENNETT: Well, I think it's already happened in some regards. I don't think we have to worry about, you know, robots enslaving us, but I think we have to worry about our own dependence on them. How much of our annual income goes to feeding the beast, buying the upgrades, keeping our cell phones and computers, which nobody needed before, now everybody needs one?

I once gave my students a fantasy about this gift from outer space that arrives, and scientists study it and sort of figure out, reverse engineer it, and then they start make thousands and thousands and millions of copies, and everyone wants to have one. And pretty soon everybody on the planet is working away so that they can have these marvelous magic boxes. We've become enslaved by these things. The only thing false about that is, it came from outer space. We got them. I think strong artificial intelligence, agents that are conscious and that treat us like dirt or slaves or whatever, that's a fantasy that's not just unrealistic, I think it's harmful because it gets us all worried about something which is hundreds of years away instead of worrying about the thing which is right here now.

CURWOOD: Daniel Dennett is a philosopher and he co-directs the Center for Cognitive Studies at Tufts University. His new book is called "From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The evolution of Minds". Thanks so much for taking the time today.

DENNETT: Thanks so much. I enjoyed the interview.

Related links:

- From Bacteria to Bach and Back

- About Daniel Dennett

[MUSIC: Greg Abate Quartet, “Bittersweet” on Motif, Whaling City Sound]

CURWOOD: Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Matt Hoisch, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Alex Metzger, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. And we welcome a new intern this week, Lizz Malloy. Lizz, we’re glad you’re here! Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org -- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page -- it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth