October 30, 2020

Air Date: October 30, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Arctic Sea Ice Overdue

View the page for this story

Amid recording-breaking high temperatures in the far north linked to climate disruption, Arctic Ocean ice is unusually late to re-form this year. Jennifer Francis, senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, speaks with Host Steve Curwood about how a delay in sea ice freeze can disrupt the ecosystems of the North and weather systems as far south as Florida. (08:40)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood take a peek Beyond the Headlines to explore reports on clean energy research that the Department of Energy intentionally stalled and buried under President Trump. Then, they look to the small town of Greensburg, Kansas, which in the aftermath of a 2007 tornado that obliterated nearly all its buildings, decided to rebuild as green as possible. In the history calendar, and still in Kansas, Wichita is the home of libertarian funder and climate change denier Charles Koch, who turns 85 this week. (04:26)

All We Can Save

View the page for this story

Despite tremendous contributions to the climate movement, women are underrepresented at international climate talks, executive leadership of environmental organizations, and the legal systems that create and uphold change. In response, an influential new collection of essays, All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis, seeks to elevate women’s voices. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, who edited the anthology with Katharine Wilkinson, speaks with Host Steve Curwood to discuss the importance of diversity and inclusion when it comes to fighting climate disruption. (14:32)

How Wildfires Benefit Wildlife

/ Aaron ScottView the page for this story

The record-setting wildfires in the Western U.S. this year have had devastating consequences for the people who have lost their homes and businesses. But as Aaron Scott of Oregon Public Broadcasting reports, many species of plants and animals depend on forest fires to create and maintain the habitat they need. (04:45)

Remembering Mario Molina

/ Paloma BeltranView the page for this story

One of the scientists who discovered how CFC chemicals deplete the ozone layer passed away on October 7, 2020. Mario Molina shared a Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery, which led to the historic worldwide ban on CFCs under the Montreal Protocol. In later life, Molina also fought to mitigate the harmful effects of climate change. Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran has the story. (06:30)

Fall Gardening Tips

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, many people found themselves stuck at home, looking for something to do just as spring was getting going. Many turned to gardening as a way to pass the time, and are looking for how to continue this new hobby into the winter. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb chats with landscape designer Michael Weishan, the former host of the PBS series The Victory Garden, about how to keep up with one’s garden and tend to plants inside and out during the colder months of the year. (09:03)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

201030 Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jennifer Francis, Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, Michael Weishan

REPORTERS: Paloma Beltran, Peter Dykstra, Aaron Scott

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

To solve the climate crisis a Black woman advocate says we need to include a greater diversity of voices and skills.

JOHNSON: We were actually at the Aspen Institute at a climate conference. And we were just like, it's the same people with the money and the power, deciding who gets the microphones, and who gets the funding for their work. And like, this just is not gonna work. Like it's just not enough.

CURWOOD: Also, as the autumn chill settles in we have some gardening tips.

WEISHAN: One of the things I really like to do is to keep a gardening scrapbook, and I urge all gardeners, to keep a scrapbook of things they like. Because then in the spring, you know what you would like to try to do. You don't have to be able to install it right now, but at least it's aspirational.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Arctic Sea Ice Overdue

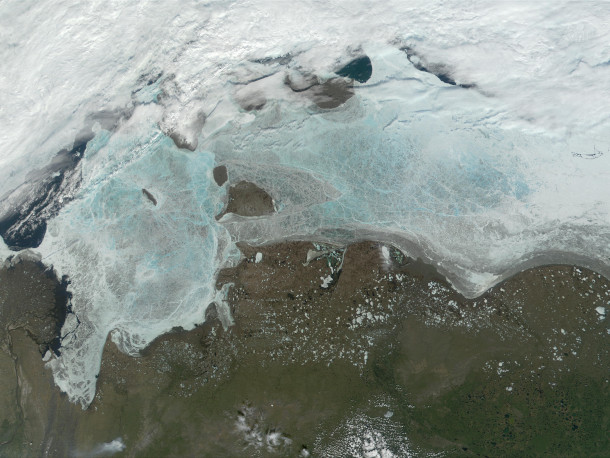

Sea ice has yet to form this year in key parts of the Arctic (Photo: Kathryn Hansen, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

You may recall the extreme winter weather we’ve had in recent years in the US, ranging from unusual warmth in Alaska, to prolonged cold as far south as Florida, even the early snows this year in the upper Midwest are all linked to deep gyrations in the jet stream. And it looks like we could be in for another winter of weather extremes thanks in part to the impact on the jet stream by the loss of sea ice in the Arctic. The main nursery for Arctic sea ice in Siberia usually starts icing over in the fall but for first time on record the Laptev Sea is ending October without its usual sea ice. Jennifer Francis is a Senior Scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, and joins us now for more. Jennifer, welcome to Living On Earth!

FRANCIS: Thank you so much for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: So tell us: Why is there a delay in the Arctic sea ice formation this year towards Siberia? What's going on?

FRANCIS: Well, the main reason is that we had a very unusual spring and summer up in the Arctic. And all around really the high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere. We lost a lot of sea ice this year. We came very close to breaking the record minimum amount of sea ice that occurs in September. It was very, very warm across Siberia this summer. We saw a record high temperature not only for Northern Siberia, but also for the Arctic as a whole of over 100 degrees Fahrenheit, it was just an astounding event. And so by losing all that sea ice in the summer, you get rid of this very white surface that reflects most of the sun's energy back to outer space, so it never enters the climate system at all. So instead, we had this very dark ocean surface sitting there, which absorbs all that extra heat, it warms up the water all summer long. And so now we've got all that extra heat that built up all summer and it's gradually escaping back to the atmosphere. But until all that extra heat escapes, the sea ice won't form because the surface of the water has to get to the freezing point. And so by having all that extra heat, it is slowing the formation of the ice this fall.

CURWOOD: And just to be clear, all that we're seeing now with this loss of sea ice is closely related to climate change.

FRANCIS: Absolutely. There's no other explanation for why the ice is going away.

CURWOOD: Now, why does this matter, and particularly to humans?

Arctic sea ice formation during the colder seasons is crucial for the climate system to regulate global temperatures. (Photo: Aerohod, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

FRANCIS: So locally, the humans who live up in that part of the world are accustomed to having that ice there so that they can go out on the ice, they hunt for animals, that's part of their traditional culture, it's very important source of their food. And when the ice is missing, it really disrupts all of their cultural traditions. And also it affects the animals that they're hunting. So by not having that ice there, we're seeing a big disruption to the food web, the marine food web. The ice generally blocks a lot of the sun's energy from entering the water; that light is needed by the algae that formed there. So, by having things very different from normal, we're seeing a lot of differences in the kinds of animals that live in the water up there -- big shifts in the ecosystem.

CURWOOD: So what you're telling me is that this lack of sea ice is related to some of the volatility in the weather that we've seen last year, when forecasters are talking about the polar vortex. There's a relationship here, I gather.

FRANCIS: There certainly is. The Arctic is a very important component of the large scale climate system. And by changing it as much as we have, meaning that literally, we've lost half of the sea ice in just 40 years in terms of how much area it covers in the summertime, that is just a tremendous change in a very important part of the climate system. And it's happened very, very quickly. And we know that by warming the Arctic so fast and reducing that North-South temperature difference, it is going to have an impact on the large scale wind patterns, which translates to our weather. So yes, by losing all that sea ice, we are definitely having an impact on both the weather patterns that we normally think of happening, but also causing more extreme weather events as well.

A delay in Arctic sea ice formation will disrupt marine food webs. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

CURWOOD: So let's dig a little bit deeper into the notion of climate disruption and what might be happening with the warming of the Arctic. Overall, it's getting a lot warmer. But yet some of the research shows that this will lead to more extremes in temperatures at lower latitudes. Tell me how that works.

FRANCIS: Right. So the jetstream is this boundary between the cold air to the north of it and the warm air to the south of it. So when it takes one of these big northward swings, say over Alaska, it allows all of that warm air from the south to penetrate way, far north much farther north than it would. And so Alaska experiences very warm temperatures. But then on the flip side of that, on the downwind side, we tend to also see these large southward dips in the Jetstream, which, in contrast, allow the very cold air from the Arctic to plunge much farther south.

CURWOOD: So in a few decades, it's likely that Arctic sea ice will continue to shrink if we stay on this trend until perhaps there's no more ice left during the summer. What do you think would happen if this downward trend in Arctic sea ice continues?

FRANCIS: Well, I don't think that downward trend is an if. It's definitely going to continue. It jumps around from year to year but overall we're seeing a very steady very noticeable downward trend in the amount of sea ice in all seasons. It's largest in the summer. But we are also seeing the decrease in the sea ice in the winter. So what's going to happen is that we expect sometime around the year 2040, it could come sooner could be a little later, we expect to see a summer where there's virtually no ice at all left in the Arctic Ocean. And if that happens, it's going to basically make all of the changes that we're already seeing happening just get worse. We're going to see even bigger disruptions to the marine food web, more difficult living conditions for the people who live up in the high latitudes, bigger changes also to the weather patterns because we're going to absorb that much more heat up in the Arctic Ocean, that extra heating is going to accelerate the melting of glaciers and the Greenland ice sheet which contribute directly to sea level rise. We're going to see that extra heat accelerate the thawing of permafrost. And when that happens, we expect to see a big release of extra carbon dioxide and methane that's basically tied up in that frozen soil. And we also expect to see perhaps some opportunities for further exploitation of resources up there. So shipping, which has been on the rise very dramatically up in the far north, because of the loss of sea ice ships can now take a much shorter path from Eurasia to the North American continent. But also there's a lot of interest in exploiting the oil and the resources that are up there. Because now without sea ice there, it becomes much less expensive and more feasible. So that's what's on the table if we continue, well, when we continue to lose all the sea ice up there.

Scientists expect the Arctic sea ice to continue to recede in coming decades until there is no more ice left in the summer. (Photo: NASA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: As a researcher whose long study this area, how alarming is this? How much of an alarm bell does this sound to you as a scientist, and actually, for us as citizens?

FRANCIS: We've been watching the Arctic change for many years in such dramatic and rapid ways that the alarm bells have been ringing for a while. This part of the world we know is sensitive to climate changes. It's been known for a long time that when the globe is a whole warms a little bit, the Arctic warms a lot more. So it really is a bellwether in terms of climate change. And finally, I think the alarm bells are starting to be heard by people other than scientists who study the region because it's having such big impacts on things like sea level rise and weather patterns and extreme weather. And we can connect those dots now for people. The research has gotten to that point where we can show these huge changes in the Arctic and how they affect everybody on the planet.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Francis is a senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Falmouth, Massachusetts. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

FRANCIS: You're very welcome. Anytime

Related links:

- The Guardian | “Alarm As Arctic Sea Ice Not Yet Freezing at Latest Date on Record”

- VICE | “Arctic Sea Ice Isn’t Freezing in October for the First Time on Record”

- Learn more about Woodwell Climate Research Center

- Learn more about Jennifer Francis’s research

[MUSIC: Esperanza Spalding, “Precious” on Esperanza, Heads Up International Ltd.]

Beyond the Headlines

The US Department of Energy Forrestal Building in Washington, D.C. (Photo: US Department of Energy, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: It's time now to take a look beyond the headlines as we frequently do with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia there, Peter. Hey, how you doing? Have you voted yet?

DYKSTRA: Oh, yeah, voted. So that gives me a few days of feeling superior to hopefully very, very few listeners of the show who haven't voted yet. If you haven't get out there.

CURWOOD: Yes, we all need to vote. Hey, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, there's a piece that involves some great digging. InvestigateWest is a feisty little nonprofit based in Seattle, who combined with online magazine, Grist. And they've uncovered or exhumed about forty clean energy studies within the Department of Energy. But the Department of Energy isn't letting them see the light of day.

CURWOOD: So what kind of studies are you talking about?

DYKSTRA: These are studies on hydro dams, energy efficiency, wind, solar, biomass, and one particular study says that about two billion in Department of Energy expenses have yielded over thirty-one billion in savings and direct benefits to American taxpayers.

CURWOOD: Hmm. You say these reports are blocked or buried. How so?

DYKSTRA: Some are published but they're published in obscure journals with little fanfare and notice, some are never released. Some are sent back to the DOE kitchen for endless reviews. There are a million ways to bury scholarly works, which is very unusual that you have an agency that in some cases is finding information that makes itself look good, and hiding it.

CURWOOD: Peter, this is shocking, the Energy Department finding that there's good things about clean energy, and that can save taxpayers money, and they don't want to tell us.

DYKSTRA: They don't want to tell us. It's just absolute further evidence of a cabinet department working against its stated mission.

CURWOOD: Yeah, that is a puzzle, isn't it? All right. What else do you have for us today?

Greensburg, Kansas in 2007, two weeks after being hit by an F5 tornado. (Photo: Greg Henshall, FEMA Photo Library, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: Well, we're going to go to Greensburg, Kansas, in the western part of the state, a little farming hamlet of 900 people. You may remember the name because back in 2007, tiny Greensburg ran into an F5 tornado, it was absolutely obliterated. 11 people died, but Greensburg saw it all as an opportunity.

CURWOOD: So what did they do?

DYKSTRA: Town leaders decided to do that scratch rebuilding and make Greensburg an absolutely model clean energy town. A lot of it was green building techniques that saved a tremendous amount of money, things like LED lighting to wind turbines. It's a success story that clean energy advocates are eager to talk about.

CURWOOD: And then of course, beyond conservation, they got in the power business, right?

The Big Well Museum and Visitor Info Center in Greensburg, Kansas. (Photo: GreensburgKansasTourism, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DYKSTRA: They got it in the power business, they sell power back to the grid from this ten turbine wind farm that they built, that not only takes care of the majority of Greensburg power needs, but brings in some money as they put it back into the grid for the remainder of Kansas to use.

CURWOOD: Okay, Peter. Well, let's take a look now back at the annals of history and tell me what you see.

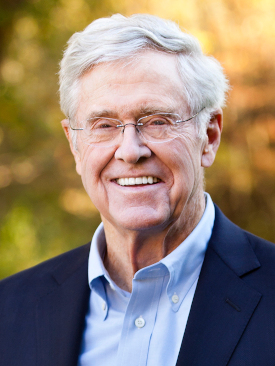

DYKSTRA: Well, we're going to stay in Kansas, we're not leaving Kansas anymore. We're going a couple hundred miles east of Greensburg to Wichita, Kansas. That of course is the domain of the Koch brothers. And on November first, Charles Koch turns eighty five years old.

CURWOOD: Well, you say Koch brothers, but I believe last year the younger one, David Koch, died.

DYKSTRA: David Koch died, David and Charles were the linchpins of Koch Industries, the largest privately owned company in America, dealing in oil and oil supplies, and dealing in a lot of politics as well.

Charles Koch, one of the Koch Brothers, known for opposing climate action and supporting climate denial. (Photo: Gavin Peters, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: And you say politically active because...

DYKSTRA: They've been a big player for twenty or thirty years on the national political scene, opposing climate action and supporting climate denial, but particularly in rebuilding state legislatures that are fundamentally anti-regulatory in states from coast to coast.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Grist | “‘It Just Goes into a Black Hole’”

- Greensburgks.org | “Rebuilding… Stronger, Better, Greener!”

- Wall Street Journal | “The Morality of Charles Koch”

[MUSIC: Preservation Hall Jazz Band, “Kreyol” on A Tuba To Cuba, by Benjamin Jaffe, Sub Pop Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Why nature needs wildfires. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Preservation Hall Jazz Band, “Kreyol” on A Tuba To Cuba, by Benjamin Jaffe, Sub Pop Records]

All We Can Save

More than 40 women contributed to All We Can Save, including climate scientist Katherine Hayhoe, author Alice Walker, and NRDC president Gina McCarthy. (Photo: Courtesy of Ayana Elizabeth Johnson)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

All too often the work of women in science is overlooked. Eunice Newton Foote is now regarded as the first scientist to publish research showing that carbon dioxide could affect the Earth’s temperature. But in August of 1856 when her paper was presented at the American Association for the Advancement of Science it was read aloud by a man. And for many years Irish Physicist John Tyndall was credited as the originator of climate science though his paper on climate came three years after Eunice Newton Foote published hers. And curiously, Mr. Tyndall would likely have known of her work as he had a paper on color blindness published in the very same issue of the AAAS journal where Ms. Foote’s climate paper appeared. Today women are still routinely underrepresented in climate science, international climate talks and the leadership of environmental organizations. To advance the voices of women in the climate movement Katharine Wilkinson, a writer, and Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, a marine scientist and podcaster, edited a collection of essays and poems. It’s called All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis, featuring 41 women who are scientists, activists, policymakers, poets and journalists and half of whom are of color. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson joins us now, welcome to Living on Earth!

JOHNSON: Thanks so much for having me.

CURWOOD: You know, sometimes people say the original sin of America was slavery, dealing with Black people, of course, women didn't have the right to vote in that constitution either. To what extent that those things need to be rectified before America will seriously deal with climate disruption, do you think?

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson (left) co-edited All We Can Save with Katharine Wilkinson. (Photo: Jennifer Robinson)

JOHNSON: And you know, one could argue certainly that the original sin was how he treated the people who are already here, the indigenous peoples, and the treaty rights that are still being ignored and stomped upon. So I think America has plenty of sins to grapple with, unfortunately, and those original sins have set us up for failure when it comes to problems where we need all hands on deck like the climate crisis. And so I think the challenge of our time is that we have to deal with all of these issues at once, unfortunately. And as much as I wish we could deal only with climate because that is certainly a big enough challenge on its own, our ability to address the climate crisis is intertwined with who has resources, whose voices are we listening to? Which leaders are we supporting? And so with this book, we were hoping to elevate dozens of women who are already doing critical work on climate and saying: these are some of the voices we really need to be listening to in this moment. And it's not that, they're not writing about being women. They're writing from the perspective of you know who they are. But these are not all essays about feminism. They're not about gender. They're essays from NASA climate scientists, from farmers, from journalists, from architects, from artists, from activists, who are all experts in their particular field and sharing their lessons about the work that they've done and the way forward. I mean, we've have an essay from Mary Anne Hitt, who's led the beyond coal campaign for the Sierra Club for a decade, which has shut down over 320, coal fired power plants in the United States, taking coal from 50% of our energy to 20% in just a decade. That's incredible. There's so much we can learn from these success stories, not just avoiding each other's failures, but actually repeating each other's successes. And so that is, I think, one of the beautiful offerings of this anthology. But one of the beautiful opportunities of this moment is to say, to look around and say, what's working? And what can the future look like if we get it right? And really lean into that sense of possibility.

CURWOOD: How did you come to the decision to edit an anthology with only female voices?

The collection includes essays and poems from scientists, journalists, policymakers, activists, and other key leaders in the climate movement. (Photo: Courtesy of Ayana Elizabeth Johnson)

JOHNSON: Because men had plenty of platforms and microphones. And the moment that Katharine and I decided to create this book, we were actually at the Aspen Institute at a climate conference. And we were just like, it's the same people with the money and the power, deciding who gets the microphones, and who gets the funding for their work. And like, this just is not gonna work. Like it's just not enough, no matter how intelligent and well meaning this small group of rich white men is, they will never be able to solve the problem on their own.

CURWOOD: So why did they invite you?

JOHNSON: I don't know. Maybe they regret it now. But I think there was this realization: oh, we're supposed to listen to women. Oh, we're supposed to listen to scientists. Oh, we're supposed to listen to people of color. Oh, how handy that Ayana is all three. I mean, that has been sort of this year, in general, for me has been one of a lot of invitations and media attention, as we are in this confluence of climate crisis and crisis of racial injustice and crisis of our democracy. But I think there is an honest goodwill from this, you know, group of people who hold the power, knowing that things have to change, knowing that we do need to bring more people in. And I appreciate that. But unless we're turning over dollars, microphones, power, decision making, along with that realization, then it's really just a token.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think attitudes are really shifting to say, well, it's not just a noblesse oblige to have some women or some people of color, but that, in fact, if society doesn't fully include everyone that it won't work?

JOHNSON: Yeah, I do think there is a realization that the status quo is clearly not working. Right? And so I think people are grasping for leadership, grasping for solutions, and having to look in places where they have not been looking before, they are suddenly seeing all sorts of things that were there. But that didn't fit what people thought of as environmentalism or climate work. And I'm really thankful that people's eyes have been pried open in the last few years. But there's still obviously so much more work to do. I mean, I think what we're seeing, you know, there's a lot of room for improvement in philanthropy, for example, when we think about whose work is funded, we know that women and people of color have a very hard time for funding their work, whereas often white men come in with like a two page summary and are given millions of dollars to give it a shot. And, you know, we need to be extending that same benefit of the doubt to people who have proven track records in their communities.

CURWOOD: One of the themes of your collection is the leadership and the need for heart centered leadership instead of just head centered leadership,

JOHNSON: Yeah.

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson is a marine biologist, policy expert, and climate activist. (Photo: Marcus Branch)

CURWOOD: Talk to me about heart centered leadership, why it's important, and in particular, the gender relationship as well.

JOHNSON: I think the way that, that a lot of people have been approaching our climate challenges for decades now has been as a technical problem, this wishful thinking, if we just got all the right engineers in a room, maybe a few politicians and rich people, too, that we could like somehow, up, just come up with a quick fix, an easy solution, as if this were really just about solar panels and electric cars. But this is a much more fundamental problem with the way that we live on this planet and with each other, and how society is structured and building an economy around fossil fuels. And so we need to transform a lot of systems, which is an unfortunately, much larger task than just getting off of coal and to renewables, right? And so this idea of heart centered leadership, is leading from a place of care, from a need to heal nature and ecosystems, as well as rifts in society, as we think about what the future looks like. And these traits of, of leading with the heart and leading with love are qualities that are sort of stereotypically associated with feminine leadership. But of course, we know that these qualities are open to people of any gender, anyone can lead from a foundation of love. And I would certainly encourage everyone to take that on. And it emerged as a theme in the book, which, when we didn't seed on purpose, and we didn't notice until we read the full manuscript. But that really is what is motivating these leaders, right? Even the scientists, it's like love of this magnificent planet, right? Like, planet Earth is incredible. And how could you not love all of these wonders? And how could you not love society and our rich cultures and all that is possible, and grandparents and children and all of it. And so I think we have this opportunity to envision an embrace, I would say, a very different way of, of dealing with climate change that is less about technology, and less about being right and more about how we bring the best of everyone to the table on sort of evolving as a society, to one where we can flourish as a part of nature.

CURWOOD: So you're trained as a marine biologist, but I don't see breathing apparatus behind you there or a bench. I think you have what, let's see, you got a book you're writing, you edited one, you have a podcast you host a couple of social service agencies that you run. So how do you see yourself as a scientist? To what extent are you like Katharine Hayhoe, who actually wrote in your book that communicating sciences really is perhaps as important as science itself?

JOHNSON: Yeah. And she's an incredible example of that. I mean, her climate research is critically important and published in top journals. And she dedicated a lot of time to making sure that that science doesn't just stay within academia, that she explained it to the public and gives everyone an opportunity to understand what the stakes are. I am no longer doing field research, scuba diving and counting fish, although I do sometimes get a little bit wistful for those days and all the all the time I spent in the Caribbean. But I think for me, we're at this moment in history where I feel like everyone needs to do an assessment of how they can be most useful, right? We are facing multiple crises at the same time. We’re facing the climate crisis. We're facing a public health crisis. We're facing a crisis of our democracy. We're facing a crisis of racial injustice and of economic inequality. And all of these are for mashing up together in this moment, and 2020 has brought all of that right to the surface in a way that we can't ignore anymore. And for me, I've spent the last four years essentially thinking about how can I be most useful in this moment, as a trained marine biologist, as someone with a lot of experience in policy, as a writer and a communicator, as a woman, as a Black person, as a Brooklyn native, all of these are core parts of who I am as, as the daughter of a Jamaican immigrant, as the daughter of a farmer. How can I be a useful part of this conversation? And so this anthology is one manifestation of that piece of how it can be most useful and, and you'll see the threads of ocean conservation come through in the curation, in the fact that we have a seaweed farmer writing about that as a climate solution, in that we have the director of resiliency for the City of New York writing about the coastal cities that she has worked in, including Honolulu and New Orleans, in addition to New York, in that we have a landscape architect writing about coastal ecosystems and how we can do landscape architecture as a way of protecting coastal communities. But I think, you know, I've had to re envision my role and what I can contribute because the world is changing so quickly.

CURWOOD: Before you go, as you and your co-editor are wrapping up the book, you make the observation that dealing with the climate emergency is "gnarly."

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson (right) and her co-editor Katharine Wilkinson (left). (Photo: Jennifer Robinson)

JOHNSON: Yeah.

CURWOOD: So expand on that for me. And what is the solution when something is "gnarly?"

JOHNSON: So to answer that question, I'd love to read a short passage from the end of the book.

CURWOOD: Sounds good, please.

JOHNSON: So the last essay has a paragraph about each of the words in the title: All We Can Save, and the "Can" paragraph I think, is probably the best way to answer your question.

[READING]

Can speaks to sheer determination. This [bleep] ain't over yet, possibility still exists as documented in data-driven analysis of climate solutions and temperature trajectories. And as imprinted in the persistence of life, despite all odds, we are a miracle. Our task and our opportunity is to face a seemingly impossible challenge, an act in service of what is possible. So what can I do? It's an increasingly prevalent question, which is a very good thing. But the answers offered are often trite, consumerist, and incomplete. And often the question should be, what can "we" do? How can we depart this perilous path? These are questions to live into every day for the rest of our lives. We can answer them and answer them again and again, by considering what good work is unfolding around us, and what invitations we may already have received, and what gifts we might have to offer or to offer more deeply. From personal acts to professional prowess to political participation, our layers of agency are more profound than we may realize. Our choices and voices, our networks, dollars and votes, our skills and ingenuity. These are all openings for "can." Enough of what we cannot achieve. Can is the drumbeat of those who refuse to give in to destruction, who rise again and again with life force.

CURWOOD: Ayana Elizabeth Johnson is co-editor of All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis.

Related links:

- Read more about Ayana Elizabeth Johnson

- Learn more about All We Can Save

- Ayana Elizabeth Johnson co-hosts the How to Save a Planet podcast

[MUSIC: Clayton March with Jacqueline Schwab, “Nicholas Baker” on In Klezmer, by Gregory R. Johnson, self-published]

How Wildfires Benefit Wildlife

Aspen recovery in the Angora Fire area near Lake Tahoe, California (Photo: Jonathan Cook-Fisher, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: The record setting wildfires in the Western US this year have burned an area larger than New Jersey, with immense devastation for municipalities and residents. But many species of plants and animals depend on forest fires to create and maintain the habitat they need. Oregon Public Broadcasting reporter Aaron Scott has the story.

GAINES: The trekking poles are helping my old man bones.

SCOTT: Ecologist Paul Hesburgh and Bill Gaines are taking us on a tour through a section of the Washington Cascades that was burned by the Tripod Fire in 2006.

GAINES: Paul, I'm not seeing a lot of woodpecker cavity activity here.

HESBURGH: I haven't seen a cavity all morning or heard any banging.

SCOTT: The reason we're looking for woodpeckers is that they are a poster animal for how scientists like Gaines and Hesburgh are reimagining fire. Instead of seeing fire as a negative thing that needs to be suppressed, they are finding it is essential to the wellbeing of many plants and animals. For example, burned forests may look barren to us. But for wood-eating insects and their predators, they are a feast waiting to happen. Gaines marvels at how woodpeckers just seem to flock in.

Black-backed woodpeckers such as this female thrive in the aftermath of a forest fire (Photo: Mike Laycock, National Park Service, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

GAINES: One thing we don't really know is there's got to be like some woodpecker hotline where they're like, “Come on, everybody! There's a lot of food let's get together and eat!”

SCOTT: And they are far from alone. From aspen to morels, from blackberries to bees. There's an incredible range of plants and animals that thrive in areas touched by fire. One of the best-known examples is the lodgepole pine, which grows what's called serotinous cones.

HESBURGH: And so every cone scale is held together by a drop of resin, and it takes the heat of a fire to melt that resin and cause those cone scales to open up.

SCOTT: The cones shed seeds that quickly grow into dense stands of young trees. And these stands are one of the only hunting grounds for one of the country's most adorable and threatened predators. The Canada lynx.

Lodgepole pine regeneration after a fire (Photo: Kent McFarland, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

GAINES: Okay, so we're gonna pretend we're a cat. We're going to pretend we're a Canada lynx. And what we want to find is our prize food, you know, a snowshoe hare.

SCOTT: Gaines crouches down in stalks his way through the thick branches.

GAINES: You can see here a scat from a snowshoe hare, so we know they've been here. Tells us this is good habitat for snowshoe hare and good habitat for lynx.

SCOTT: That's because these young pines are like a goldilocks zone. They're just right, big enough to provide shelter for the bunnies with branches low enough for them to hide under. But as the pines grow taller and their branches no longer touch the ground, the bunnies and the lynx that hunt them have to go in search of new stands. As Hesburgh explains it, few northwest animals have evolved to live in thick, unchanging forests. Instead, most need an evolving clumpy mosaic of landscapes to meet all their needs. And the main driver behind that constant process of change and renewal is fire.

HESBURGH: If you were to roll the film back a hundred, hundred and fifty years in history and take a look at a big landscape panorama, what you would see is places that were burned yesterday, places that were burned five years ago, ten years ago, that create this variety of habitats.

SCOTT: But decades of fire suppression have transformed that landscape.

The Canada lynx relies on young lodgepole pine stands as perfect snowshoe hare hunting habitat. (Photo: Eric Kilby, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

HESBURGH: Where the forest is all grown up and blended. There are some critters still making a living in that landscape, but it has nowhere near the variety of the former landscape before it was homogenized.

SCOTT: Today's thick forests combined with a warming climate also set the stage for megafires. The result is two starkly contrasting landscapes and a dynamic far different from the one native animals evolved with. Gaines says the loss of that varied habitat for creatures like the Canada lynx has been devastating.

GAINES: Lynx recovery is either made or are not here in this part of Washington. This is the largest population in the lower 48 states.

SCOTT: And it doesn't stop there. Fire has a crazy interaction with water by helping to thin out dense spreading forests, it actually leads to more water flowing into wetlands and streams. That encourages rich cool dining rooms for everything from gear to fish. No one is advocating that we let all fires burn freely, especially the human-caused ones. But a consensus is emerging that as crazy as it sounds, we need to restore regular fire to the land to help our fellow plants and animals survive.

CURWOOD: Aaron Scott’s story comes to us courtesy of Oregon Public Broadcasting.

Related link:

OPB | “Why Many Northwest Animals and Plants Need Wildfire”

Coming up – we remember Nobel Prize winning chemist Mario Molina. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: John Williams and Friends, “Township Kwela” on The Magic Box, by Timothy Walker, Sony Classical]

Remembering Mario Molina

Mario Molina received the presidential medal of freedom from President Barack Obama for his work on helping save the ozone layer. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mario Molina Center)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Back in 1974 scientists started calling for the protection of the ozone layer, much as they are sounding the alarm today to protect our climate. At the time chemicals known as Chlorofluorocarbons or CFCs, were used in everything from refrigeration to hair spray. CFCs were making holes in the thin layer of ozone high in the sky that protects life on Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation from the sun. The discovery linking CFCs to ozone depletion was made by two scientists at the University of California at Irvine named Sherwood Rowland and Mario Molina, and they shared many prizes for their work. Professor Rowland has been dead since 2012, but Mario Molina died at the beginning of October just this year. We pause to remember Mario Molina for his part of the discovery and also the hard work he did to help convince the world to ban those chemicals, and after a dozen years the whole world finally listened to science and acted to ban CFCs in 1987 under the Montreal Protocol. Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran has more.

BELTRAN: In 1974 Sherry Rowland and Mario Molina published a paper in the journal Nature highlighting the science of CFCs and the chemical’s responsibility for weakening the ozone layer. It was ridiculed.

ZAELKE: When he first published his paper with Sherry Rowland, they were vilified by the chemical industry. They were attacked. They were not invited to meetings of chemical societies.

BELTRAN: Durwood Zaelke is founder and President of the Institute for Governance & Sustainable Development and he was a long time colleague and friend to Professor Molina.

ZAELKE: They were shunned by their peers. And it took a lot of courage to fight back. Scientists don't always do this. But Mario and Sherry showed us what an advocate scientist or a science advocate could be like. And this was absolutely critical.

Mario Molina was born in Mexico City and expressed a strong passion for chemistry and science since childhood. He graduated from the University of California Berkeley in 1968, joined the faculty of MIT in 1989 and came back to California to teach environmental chemistry at the University of California San Diego. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mario Molina Center)

BELTRAN: Professor Molina’s advocacy was crucial for establishing the scientific urgency that culminated in the 1987 Montreal Protocol, a global agreement to protect the stratospheric ozone layer. It was signed by 197 countries, every country in the world, making it the first treaty in the history of the United Nations to achieve universal ratification. Durwood Zaelke credits that success to Professor Molina.

ZAELKE: He worked tirelessly as an advocate, to advance the protections that we needed to solve the problem that he identified.

BELTRAN: But that’s not something that scientists, then or now, are typically comfortable with.

ZAELKE: I mean, this is not what scientists always do. It's happening more on the climate side today. But all the climate scientists have Mario as an example, and Sherry Rowland, his colleague, and so they can say well if Mario and and Sherry Rowland did this, maybe I should stand up and be a stronger advocate.

Mario Molina (left) and Durwood Zaelke (right) after successfully committing countries to phase out the use of the hydrofluorocarbons, which were substituted for ozone depleting gases, but proved to have a strong greenhouse effect and added to global warming . (Photo: Courtesy of Durwood Zaelke)

BELTRAN: In 1995 Professor Molina became the first Mexican-born scientist to receive the Nobel Prize in chemistry. He was a world famous scientist but colleagues like Gaby Dreyfus the senior scientist at the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development routinely describe him as down to earth and approachable.

DREYFUS: I was super nervous when I found out that I was going to meet him in person. But he was the most kind, welcoming person. I remember sitting in his office and being treated like I belonged at the table. He was an incredible gentleman.

BELTRAN: She says he was adamant that his research should be used for public benefit.

DREYFUS: He shared with me his passion and dedication to doing science in a way that serves society essentially, doing the work that takes the science from the lab to make a difference in the world.

BELTRAN: And he continued to make a difference in the world by focusing his scientific research and advocacy on the existential threat of climate change. Durwood Zaelke was with him at an international meeting in Kigali, Rwanda where they successfully urged some 150 countries to eliminate HFCs, a potent greenhouse gas.

ZAELKE: Those chemicals by phasing them down under the Montreal Protocol, we can avoid up to a half a degree Celsius of future warming. So Mario was one of the people who saw the potential and then worked on science, but then, behind the scenes on diplomacy.

BELTRAN: In 2016 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama.

BELTRAN: In a speech following the medal of honor ceremony Professor Molina spoke about why it is important for scientists to work with policy makers.

Mario Molina was the environmental policy advisor to the President of Mexico Enrique Peña Nieto. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mario Molina Center)

MOLINA: What does it take to change people's behavior? What does it take to implement policies? But even within the field itself, of addressing, say, a large environmental problem, you need different branches of science. But you also need to communicate to economist to lawyers and putting all this together is how you can get the society to improve.

BELTRAN: Professor Molina continued to work on the climate change problem to his last days. His final article was published after he passed away. It was an op-ed written with Durwood Zaelke that laid out a 10 year plan to reduce HFCs and mitigate climate change.

ZAELKE: So this now is, in a sense, a sacred text. It is Mario's last. It’s his instruction to us. And, I will be doing everything I possibly can to honor him with further work, and I miss him. He was a good friend.

BELTRAN: Professor Molina passed away on October 7,2020. He leaves behind a legacy of excellent research and scientific advocacy that serves as an inspiration for the enormous scientific challenges of our time. Thank you Mario Molina. For Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran.

Related links:

- Bulletin of the Atomic Scientist | “‘Mario Molina an Appreciation from a Colleague”

- The Guardian | “‘Mario Molina Obituary”

- MIT News | “‘Institute Professor Emeritus Mario Molina, Environmental Leader and Nobel Prize Laureate Dies at 77”

- Watch Mario Molina give an inspirational speech in the Science Museum of Minnesota

- Watch Mario Molina’s speech after receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom

[MUSIC: Biff Smith, “First Rain” on Biff Smith Solo Piano, by Biff Smith, Callipygous Music]

Fall Gardening Tips

One option for gardening during the colder months is building a hoop house, a kind of DIY greenhouse to help extend the growing season. (Photo: Jo Zimny, Flickr, CC BY-ND-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now that the chill of fall has settled on many of us, especially in the north, it might seem like gardening season is a distant dream for next year but it doesn’t have to be, according to Michael Weishan. Michael is a landscape designer and former host of the Victory Garden on PBS, and years ago he did a regular gardening segment here on Living on Earth. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb is our resident gardener, and she caught up with Michael for some fall gardening tips.

BASCOMB: So we talked with you, Michael, at the beginning of the pandemic, back in the spring, about taking up gardening as a way to keep busy. And apparently a lot of people did that this summer: garden stores sold out, seeds were hard to come by, did you have that experience as well?

WEISHAN: Absolutely. Thanks to our advocating, of course, people ran out and bought up a ton of stuff. It was crazy. If you went to the nurseries in the springtime, I mean, it was the one thing that people could do. They were mostly open nationwide. And supplies just went immediately. If you were trying to buy seeds in April, it was over and out. And very difficult too, for supplies in general, just things like fertilizer and timber. And if you were gardening this summer, you were you were doing a really heartfelt job because it wasn't the easiest summer to be an avid gardener.

BASCOMB: Well, what advice do you have for someone that maybe decided, okay, I'm going to take up gardening and found it frustrating? Or it didn't work out, you spend all this time and energy and money in many cases, and you don't get much on your return. That can happen. What advice do you have for somebody like that?

WEISHAN: Well, you know, it's not unexpected. If you start any hobby, try playing tennis like a pro on your first day out. There's a big learning curve in gardening and so my advice is not to be discouraged. Chances are you got something out of it, if nothing else than exercise. So if you look around and say, well, I lost the tomatoes, but I got the beans, I got the flowers, but I didn't get the fruit. You're ahead of the game. Whatever comes comes and don't fret the rest, is I guess my my advice. And don't give up. I think that's the other thing. I think people have a tendency, when they don't have these incredible, beautiful results right away, they say oh, this is impossible. I can't do this. You can! It just you know, it takes skill. Thomas Jefferson was famous for noting at age 80-some that he was a very old man, but a very young gardener. And that's really true. That's really true. It takes a lifetime to learn. So just get out and enjoy.

BASCOMB: Well, what are you growing this time of year? I mean, we're supposed to get snow in a few days here in New England, it's certainly getting chilly, what can you still be doing this time of year in your garden?

WEISHAN: The thing to do is to start to be cleaning up your garden. The pests and problems that you've had over the course of the year, generally overwinter in the debris. So the better you can begin to clean out the space, remove the old foliage, put away the tomato cages, etc. The better off you'll be for the spring. Secondarily, you know, now is the perfect time of year to plant bare root plants. A lot of plants can be shipped in the fall, like peonies, that are very expensive to buy in pots in the spring. Now you can buy them and they come bare root, you plant them now. And in spring you have the flowers. So, great time for that. Also a great time for bulbs, spring bulbs. I'm planting both outdoors, boy, am I planting. I started last year trying to improve our bulb display because it had kind of gone downhill for quite a while. And was I ever grateful last spring to have these huge swathes of flowers, you know, right during the middle of the COVID experience. So, I don't know if a lot of your listeners have tried forcing bulbs, but it's very easy to do, it essentially means that you're forcing them out of season, so that you're forcing them to bloom at a time that they wouldn't normally bloom. So, you plant them up in pots now. You have to make sure that they're chilled, they need a period of cold. And you can do that by just leaving them outside on a fire escape or in the backyard. Then, bring them in into a cool place. And then bring them into the house over the course of succession over the months in January, February, March. So you'll have these pots of flowering bulbs in your house. So it's an incredible indoor gardening experience for pennies, really. I don't know, maybe for 30 bucks, you can buy 100 bulbs, and bring these in in a succession of pots and bring them in every week or so. And so your entire, you know, spring are filled with flowers for pennies.

Michael Weishan grows a multitude of trees, flowers, and other plants in his backyard. Pictured here is his beloved paw paw tree. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael Weishan)

BASCOMB: Now, what about growing in a hoop house or a cold frame? Those are basically like a small greenhouse that you can build yourself. Can you give some advice about how to get started with something like that?

WEISHAN: Yes, I can. Now, for the far north, it's pretty impractical to do because - and by far north, I mean, Growing Zone 5 and above, it gets very hard to do this unless it's heated in some sort of way because the temperatures just drop to freezing and everything freezes out. However, if you're in the more temperate areas of the country, especially like the Pacific Northwest, you can grow greens in these little houses right through the whole course of the winter. And greens are really the primary crop for winter gardening, because a lot of vegetables are daylight-specific. They require either rising level of light every day or decreasing level of light every day in order to come to maturity. Greens are pretty much 'I can grow anytime of year' kind of plants, provided it's you know, not freezing and provided they have the right light conditions. So if you wanted to start with something like that, now's a great time to do that. You can also overwinter a lot of things. A friend of mine has an incredible collection of these bright red French geraniums. And at the end of every year, she just cuts them all back, gives them a little dose of water, throws them in a cold frame. And there they overwinter, with a little mulch, until next spring. And then she starts them all over again. Talk about cost savings, because I think she paid $20 or $30 apiece for these things to begin with. You know, the other thing you can do is propagate stuff like that. I mean, if you have just a slightly warmer experience, you could take those same geraniums and propagate, you know, pieces of them. So there's a lot of stuff to do.

BASCOMB: You mentioned earlier about bringing bulbs indoors and forcing them to bloom through the winter for you. But what else can you grow inside, say, on a windowsill? Or even if you invest, you know, $30, $40 in a grow light, what can you still grow through the winter other than bulbs?

Jasmine is one of Michael’s suggestions for plants to grow indoors – especially because of their wintry scent. (Photo: x70tjw, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

WEISHAN: Well, almost anything, you know, whatever your horticultural heart fancies, frankly, especially if you have the grow light. That really makes a big difference. I'm always looking for different types of plants that have winter scent. There's a whole group of plants like the jasmines, that bloom in the middle of winter. I've saved this jasmine now for, I don't know, 40 years, and I've hauled it around with me every place I go, and it goes out in the summer, and it comes back in in the winter. So you know to me, things like, plants like that. And I'm always searching for new ones. I'm watching the British gardening shows, I'm watching anything I can find to tell me what plants are new and interesting, potentially for winter blooms and flowers. So, you know, just I would urge your listeners to keep your eyes open and to think about scent in the winter, because it really is the, it just adds a whole new level of experience to indoor gardening.

BASCOMB: Yeah, that's a wonderful idea. If you're looking to start a garden in 2021, what should you do now to prepare for that? I mean, a lot of us spend the winter ogling over seed magazines. And you know, dreaming of what could be But what should you get started with now?

WEISHAN: One of the things that you can do in the fall, especially for people who are thinking about vegetable gardening, or now is to take all those leaves that you would be taking to the transfer station, or composting or you're trying otherwise to get rid of, and just piling them up where you intend to be gardening for the next year. So you would form an enclosure of some sort, let's say with snow fencing, or with timbers, and then I would start piling these leaves into it. Right on top of the lawn. And by the spring, the lawn will be dead and composted. And then you just till in the leaves, into the soil. So you have this incredible gardening bed, prepared by Mother Nature. One of the things that I am interested again this year, is taking better care of my tools. I have been really bad, historically about tool care, with the idea that well, you know, there's always another one around the corner kind of thing. How stupid! Good tools are expensive, they last a lifetime. And if they are taken care of in a very simple sort of way, i.e. Michael does not leave them outside all winter long in the garden, then they last a lifetime. So I've been trying to, you know, be better about tool organization. I've been trying to also, one of the things I really like to do is to keep a gardening scrapbook. And I urge all gardeners, and certainly my clients, to keep a scrapbook of things they like, because then in the spring, you know what you would like to try to do. You don't have to be able to afford it right now. You don't have to be able to install it right now. But at least it's aspirational. So, by all means just keep a notebook and get ready for next year because it's got to be better than this one. It's got to be better than this one.

Gardening journals or scrapbooks, like this one, can be a good way to stay connected to your garden and plan for next year. (Photo: Andrea_44, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Gardening guru Michael Weishan, speaking with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

Related link:

Click here to contact Michael Weishan and learn more about his landscape design work

[MUSIC: Biff Smith, “It Might As Well Be Spring” on Bill Smith Solo Piano, by Rodgers and Hammerstein, Callipygous Music]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Leah Jablo, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aaron Mok, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Casey Troost, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth