July 2, 2021

Air Date: July 2, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

DNA Barcoding for Quick Species ID

View the page for this story

Roughly 1.3 million species have been identified and recorded, but that’s just a fraction of life on our planet. A recent advancement known as DNA barcoding samples small but key parts of genomes to ID species. Paul Hebert, lead scientist at the International Barcode of Life Consortium, explains the process and what it could mean for cataloging biodiversity. (08:17)

Midtown Coyote

/ Berry JunghansView the page for this story

In an era of remote learning and spotty Zoom meetings, we humans still have it easier than many animals trying to raise their young. Writer Jennifer Berry Junghans on how a mother coyote manages to eke out a living in the heart of California’s capitol. (04:37)

Coyote On The Beach

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Through a combination of gestures, pitch and volume, herring gulls are able to “speak.” With each variation of visual and linguistic components, these gulls are able to vocalize “phrases,” communicating alarm calls and signals. Take a listen as Living on Earth's Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender narrates a scene of herring seagulls taking a stand against a coyote. (02:34)

Ubuntu and Unity for Healing

View the page for this story

The U.S. is extremely divided in many ways, from politics to race to wealth. But for a model of unity, we might look to the African concept of Ubuntu as a way to heal the many broken relationships in America. South African physician and anti-apartheid activist Mamphela Ramphele speaks with Host Steve Curwood about how Ubuntu can bring communities together and support individuals at the same time. (13:00)

BirdNote®: Insects Are Essential

View the page for this story

Insects sustain our ecosystems, as a food source and pollinators of 90% of all plants, but their numbers have dropped by half in the last 50 years. However, growing certain plants directly benefits birds and helps insects keep the natural world ticking. BirdNote®'s Mary McCann has the story. (01:57)

The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World

View the page for this story

Insects far outnumber us on this planet, and they’ve shaped the course of human history. Edward D. Melillo, the author of The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to share stories about the ancient relationship between human society and insects, and the critical need to preserve insect biodiversity for future generations. (16:37)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Paul Hebert, Mamphela Ramphele, Edward Melillo

REPORTERS: Jennifer Berry Junghans, Mark Seth Lender, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX- this is Living on Earth

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

We share the earth with roughly 10 quintillion insects or maybe they share it with us.

MELILLO: Really in a lot of ways this is an insect planet that we’re just happening to live upon at this moment. Insects are governing all the basic processes that make life possible from plant sex to decay and all sorts of other crucial ecosystem services.

CURWOOD: Also, ancient African wisdom for relating to each other and the earth.

RAMPHELE: Our ancestors began to understand that the only way they can not only survive, but thrive is by working together to relate to one another in a way that says: I am because you are.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

DNA Barcoding for Quick Species ID

Samples of an organism’s genome are obtained in the field, before being brought back to the lab for the barcoding process. (Photo: Natasha de Vere & Col Ford, Barcode Wales, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Modern society has yet to record all the species on our planet but we do know that the 1.3 million we’ve registered so far represent just a tiny fraction of the abundant life on Earth. To make it easier to identify species, the International Barcode of Life Consortium is using a technique known as DNA barcoding. It can give a quick readout that tells whether a sampled organism is known to modern science, and if not provide a marker to register it as a newly discovered life form. Paul Hebert is the molecular biologist who developed DNA barcoding. Paul, welcome to Living on Earth.

HEBERT: Yeah, thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, take us through the process of DNA barcoding. You find an organism you want to identify, and then?

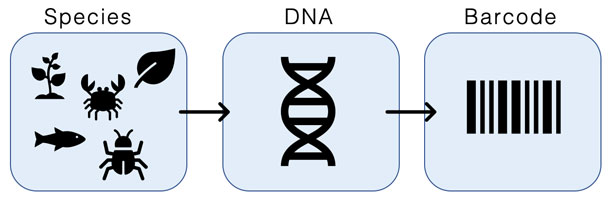

A simplified flowchart of the process of DNA barcoding. (Photo: LarissaFruehe, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0))

HEBERT: Well, I mean, you might just touch it, would be the simplest thing, and pick up enough of its DNA. I suspect you wouldn't like me to do something more destructive with you, so, simply touch you and I would pick up enough DNA off your surface, any vertebrate. But in the case of smaller organisms, where we may be prepared to sacrifice them, and where we want to have a voucher specimen in a collection that we can look at, and photograph and analyze in other ways, we might remove a tiny piece of tissue. If it were an insect, six legs, remove one of those legs and extract the DNA from that. That's a fairly simple process. When you do that DNA extraction, of course, you get all of the DNA in the genome, in your case, it would be about 7 billion base pairs. In the case of an insect, it might be 500 million base pairs. And we just want to read 500 of them. And you can think of the whole genome as sort of a book of life. And we want to read just one of those pages. So to do that, we use the polymerase chain reaction, which basically Xerox copies a selected page in that much larger book of life. And that prepares us then, once we've got many copies of it, prepares us for doing the next stage, which is sequencing the DNA. And that delivers the barcode record.

CURWOOD: Now, when somebody identifies a species and generates that barcode using these techniques, where can that information go from there? And what can it do?

HEBERT: Well, I mean, of course, that was the first thing we saw coming, was a very large number of records. So, it was important to develop an informatics platform that's now been adopted by the global community. It's a platform called the Barcode of Life Data System, acronym 'BOLD'. And basically, all of the data from each individual specimen go into that database, together with an image of the specimen and where it was collected, and by whom; all of the details. And so, let's say you begin by sequencing an American Robin, next time you were to encounter a feather on your lawn that happened to derive from that bird species, you would get a connection to that reference sequence in the bar code library, in BOLD. Now, if it came from a bluejay, and there was no reference sequence in the library, you'd be in a bit of problem. But the idea is to build up this reference library, so it has representative sequences for every species on our planet. And that's what we're in the process of doing now.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, this is a very handy approach in academia with nice big laboratories. What about somebody who's in the field? How useful is this?

HEBERT: Well, you can go in the field, as we have recently, in Kruger National Park with the rangers in that park, who normally are involved in suppressing poaching of rhinoceroses, joined in a massive collection program that gathered up about a million specimens from that largest national park in South Africa. So they gathered the specimens, they worked in the field, did all the field work, and then they dispatched them to our core facility. And we then translated those specimens into barcode records and built a DNA barcode reference library for Kruger National Park. So that's one way you can do it. But in the future, it's going to be certain that you're going to be able to take a walk through the woods with your kids or your grandkids, and see an organism, and simply touch it, and from its DNA barcode sequence, gain its identity, and everything else that humanity knows about it. And we're heading there within the next 10 to 20 years for sure.

CURWOOD: What's your biggest surprise now, in this project? What have you found or what have other researchers found using DNA barcoding that we just never would have understood or been many, many years before we could understand?

HEBERT: Well, I think there are a few surprises. I happen to be a bit passionate about insects, the most diverse group of life on our planet. And for a very long time, it has been argued that beetles were the most diverse group of insects, the most diverse order of insects. In fact, the famous British biologist Haldane was, this was one thing we could learn about the mind of God: by studying life on our planet, that he had an inordinate fascination with beetles. But it turns out that's wrong. Barcoding revealed that flies are by far the most diverse group of insects. And more so, that one particular group of flies, gall midges are hugely diverse, more diverse than all of the beetles on our planet. So, this was something that hadn't been observed, despite 260 years of scientific investigation of multicellular life on our planet. But it was revealed quite quickly through barcoding.

Paul D.N. Hebert is the Canadian biologist who developed the technique of DNA barcoding. (Photo: Courtesy of the International Barcode of Life Consortium)

CURWOOD: By the way, give me some examples of where DNA barcoding has found species in places where you just had no idea they were there.

HEBERT: Well, one of the earliest studies that we did in Costa Rica, involved a beautiful iridescent blue butterfly that for the last 200 years, has been regarded as a single species. Had one thing that was a bit unusual about it, it fed on an inordinate diversity of host plants. And when we barcoded that species, we found that in fact, it was 10 species, not one. There's a lot of hidden diversity, even within the large species that we share on this planet, when you move down to the small stuff, it's massive discovery.

CURWOOD: Now, the International Barcode of Life Consortium has this mission of identifying each and every species on Earth using barcoding. What is the ultimate goal of the project, do you think?

HEBERT: Yeah, well, I think there is this curiosity element. You know, we really do want to understand the diversity of life that... the planet, the organisms we share this planet with. However, that knowledge, creating that reference sequence library for all species on the planet, is going to place us in a position where it's going to be possible for us to set up global bio surveillance system. So we can track what humanity is doing to the other life forms. So, just like in the 19th century, we began to record weather. And we're now... have the information that supports global warming and change and it's leading to shifts in the way we power our society. We're taking adaptive actions to prevent further global warming. I see detailed information on the shifts in biodiversity that are happening on our planet, motivating humanity to take the action needed to do better. And I think the other major contribution will be setting aside all of these DNA extracts, so we can read the books of life at our leisure. Most species, when they go extinct, aren't like the dodo, where you could go and find bones 200 years later, or the mastodons. Most species when they become extinct, are a smudge on the forest floor for a day or two. And that book of life is gone. So I think humanity will be very grateful that we've preserved the books of life for reading, and hopefully have changed human behaviors so the species aren't just in a freezer. They're sharing the planet with us into the future.

CURWOOD: Paul Hebert is a molecular biologist at the University of Guelph in Canada, and science director of the International Barcode of Life Consortium. Thank you so much, Paul, for taking the time with us today.

HEBERT: Cheers. Thank you very much, Steve.

Related links:

- The International Barcode of Life Consortium

- Science Magazine | “$180 Million DNA ‘Barcode’ Project Aims to Discover 2 Million New Species”

[MUSIC: Dana Robinson, “Crossing the Platte” on National Parks: America’s Best Idea, by Dana Robinson, PBS]

Midtown Coyote

The coyote darts across a street in Sacramento. (Photo: Jennifer Berry Junghans)

BASCOMB: Isolating during the pandemic put a spotlight on the challenges of parenting in the absence of childcare. Still, we humans probably have it easier than many animals trying to raise their young. Here’s writer Jennifer Berry Junghans on how a mother coyote manages to eke out a living in the heart of California’s capitol.

JUNGHANS: She dug her den in the dense ivy butting up against the sidewalk in a residential neighborhood of midtown Sacramento. A fresh mound of dirt at the entrance of her 10-foot burrow gave it away, behind caution tape that warned passersby to keep out.

The mother coyote dug her den in dense ivy along a midtown sidewalk. (Photo: Jennifer Berry Junghans)

I meet up with a friend. Within minutes we see her in the parking lot behind us. She rests under a southern magnolia but looks tense.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Calisson,” Confectionery, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

She glances left, right, forward, back, like hands on a clock gone mad.

I wonder if she wonders where her two pups are. They’re 11 weeks old now, still small and cuddly to the eye but independent enough to roam the city without her. I think of the possibilities of what could go wrong. I think of her natural habitat along the riparian corridor of the American River, where pups play and tumble on golden knolls as moms watch nearby. A land she knows, rules even. A land where she is at home.

The mother coyote and one of her two pups. (Photo: Guy Galante)

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Calisson,” Confectionery, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

But here in the city, it isn’t long before a man barrels into the parking lot and chases the coyote with his car. It’s distressing to see and it brings to life the tension of this scene. Some people are thrilled to share space with her and her pups. Others want them eradicated, like the man in the car. Some are fearful, some are fearful for them, and others pour bags of cat food on the ground, unintentionally habituating her to this booby-trapped urban setting.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Calisson,” Confectionery, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

She’s agitated now, jumpy and uncertain as she bolts across the street and wanders through lanes with the swift leggy gait of a moving target. She locks eyes with me as she moves and I swear she can see through me. Moving through the intersection, she boomerangs back across the street, darts through parked cars, then down the sidewalk and heads my way. She sees me, and ducks into overgrown landscaping. I spot her again about 20 minutes later, grabbing a few mouthfuls of cat food. Something startles her. She jumps straight up in the air and lands a few feet away in the street.

“I swear she can see through me,” Junghans writes of the mother coyote. (Photo: Jennifer Berry Junghans)

I think about my choice to come see her. To bear witness to her experience, but my good intention is stripped down naked. I am just one more encounter she must gauge and respond to in this calamity of human activity.

State laws say she can’t be relocated. Even if she could, she may not find adequate food or water. And if she’s moved to a dominant coyote’s territory, he may attack her and kill her pups.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Calisson,” Confectionery, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

So the plan is to keep the peace between man and beast, discourage her presence and hope she returns to wilder land.

It’s unlikely this will be the last time a coyote makes her den in midtown. We see them more and more, comingling in the spaces we call home. I wonder if one day we’ll mirror London, where wild red foxes that live among the urban neighborhoods are as common as cats lounging outdoors and people walking their dogs.

Both mother and pup are always on the lookout for danger. (Photo: Guy Galante)

But for now, we have no unity among our understanding of these animals or in our ability to live in harmony with them.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Calisson,” Confectionery, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

Eventually, I go home. And her struggle continues on.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Calisson,” Confectionery, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

BASCOMB: Writer Jennifer Berry Junghans with her essay, “Midtown Coyote.”

Related links:

- About Jennifer Berry Junghans

- A previous segment on LOE featuring Jennifer Berry Junghans: "Wildly Magical: Animal Encounters in the Galapagos"

- More from Jennifer Berry Junghans on LOE: “The Pear Tree”

Coming up – Some ancient African wisdom on bringing people closer to each other and to their environment.

Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Carrie Rodriguez, “Seven Angels On a Bicycle” on Seven Angels On a Bicycle, by Carrie Rodriguez & Chip Taylor, Train Wreck Records]

Coyote On The Beach

To warn others of danger, herring seagulls use a series of volume modulation, syllables, and even visual gestures to communicate. In one such instance, a herring seagull spots a coyote on the beach and lets out a loud warning cry. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. We travel to Connecticut with Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

LENDER: The herring gulls are circling. They wheel and wheel as they move down the shoreline calling, Look! Look here! Look out! That’s what their voices mean. Thin. Uncertain. A frisson that passes through the flock.

It is impossible to see what they see. The sun is never awake at this hour. The only light is a muddy reddish stain that pulls up behind them in the sky. What disturbs the herring gulls must be close enough to be a threat or at least, seem out of place. Like house cats they notice anything they are not used to. Even the crack in the seawall that opened after the storm which they did not like at all. They are low, maybe fifty feet, and almost overhead now -

and there it is.

Instead of Up I should have been looking down:

Coyote on the beach!

Young, thin, long-legged, he looks more wolf than Song-dog except for the lack of confidence. He glances over his shoulder at the gulls, and again, and then -

He sees me looking right at him.

Coyote loses his trajectory and strays across the tideline. Saltwater lifts in silver arcs from his paws, splashes down, it sounds like the clinking of glass. Other than this he is silent, does not open his mouth, not even to gasp for breath, and continues. Staring as he passes then loping almost at a run.

Herring seagulls have scavenging habits which take them to open ocean water and spaces, like the beach. They prey on marine invertebrates, fish, insects, and crabs and crayfish. Always on the lookout for anything out of the ordinary, they communicate signals and warning calls to each other. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

The gulls have given Coyote away. A Human has found him. The thing he feared.

At a large breakwater a hundred yards on he bucks up and at the top, stops and looks at me one last time. Then turns, down between the boulders, and again onto the sand and settles into his stride going west at a steady trot until in the grayness and the distance he is lost from sight...

The herring gulls disperse.

Everything is back to normal.

BASCOMB: That's Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Read the Field Note for this essay

- Check out Smeagull's Guide to Wildlife

- Read Mark Seth Lender’s book on seagulls: Smeagull the Seagull

- Learn more about author and photographer Mark Seth Lender’s work

- Special thanks to Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge

[MUSIC: Eduardo Bartolotti/Pascual Cerezo, “The Bee” by Franz Schubert]

Ubuntu and Unity for Healing

Dr. Mamphela Ramphele is a physician, activist, and founder of the Agang South Africa political party. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: The US is extremely divided in many ways from politics to race to wealth. But for a model of unity we might look to the ancient African concept of Ubuntu as a way to heal the many broken relationships in America. Mamphela Ramphele explains in an essay for the book The New Possible how Ubuntu can bring communities together and support individuals at the same time. Mamphela Ramphele is a South African physician and anti-apartheid activist and she joins us from Cape Town.

Welcome to Living on Earth!

RAMPHELE: Thank you very much for having me, and greetings to your audience.

CURWOOD: So, what are the principles of Ubuntu, and why are you writing about it now?

RAMPHELE: The principles of Ubuntu are the original wisdom of all our common ancestors, because remember, all human beings originated here in Africa. And it is that wisdom that our ancestors began to understand that the only way they can not only survive, but thrive is by working together to relate to one another in a way that says: I am because you are. But also, they developed a very deep reverence for nature. So Ubuntu is not just about the interrelationships and interdependence between human beings, but also between human beings and all of nature's life.

CURWOOD: I am because you are.

RAMPHELE: Yes indeed.

CURWOOD: In a broader sense, what is this, "I am, because you are"?

RAMPHELE: When I say "I am, because you are" I am saying to you: I will do everything that I know you need to thrive so that you can do the same to me, because the best life insurance for any species in an ecosystem is contributing usefully to the well being of other living species.

A map of South Africa, with Dr. Ramphele’s home province of Limpopo, highlighted in a lighter gray. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 1.0)

CURWOOD: In the essay that you wrote, you say that you learn the tenets of Ubuntu from your elders growing up in a rural South African village in the province of Limpopo, not too far from a lot of big animals over there at the National Park. What did it look like growing up in that community?

RAMPHELE: Absolutely idyllic. We were at the foot of the Soutpansberg Mountains, and we had a huge extended family. You were taught the values of Ubuntu, not by saying "you must do this, don't do that", but by being told, "no my dear child, a person does not do that". So not to live by the values of Ubuntu is defining yourself out of the family of human beings. And when you do something great, they say, "that's what a person does". So we were affirmed in this way of life, this philosophy of life, that was all encompassing. And so this is the beauty of multi generations growing up in the same household.

CURWOOD: So another way to summarize this perhaps is that looking through the lens of Ubuntu, there are no individuals, there's simply members.

RAMPHELE: There are individuals to the extent, and this is an important part, to the extent that you are recognized as a very unique being, with unique talents. And I was the tiniest, I could never do anything like run, but I was made to believe that, no, no, you have other things that you can contribute. And so my dad used to tell me, use your brain because you haven't got any physical abilities. So it wasn't that you were part of a collective that submerged your individuality, but you were taught that your talents and your individuality will thrive within this collective affirming Ubuntu network.

CURWOOD: Now, one key concept of Ubuntu is affirmation. What exactly is affirmation in this context?

RAMPHELE: Affirmation is respect for people because they are human. And that respect is exhibited by treating other people the way you want to be treated. And it also is recognized by neuroscientists today, that humiliation is the worst trauma you can visit upon another person. So as a nation is precisely to counter any suggestion of treating people in a way that humiliates them.

CURWOOD: And the impact of being humiliated is, as you say, devastating.

RAMPHELE: Absolutely devastating. Because unfortunately, one of the consequences of it is that the person humiliated loses self-respect, loses reverence for life. And because they are humiliated they won't attack the attacker, they tend to attack those closest to them, and they tend to attack people who look like them. And, of course, there is a lot of self mutilation that happens, whether through drugs or through other forms of self destruction.

The Entabeni Game Reserve in Limpopo Province. (Photo: Fyre Mael, Flickr, CC-BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, in your essay, you talk about how these things are passed from one generation to the next. How has humiliation had such an impact in Africa, and for that matter, in the United States for generation after generation. Who has been affected by this?

RAMPHELE: The trauma of humiliation visited upon ancestors those many years ago through slavery, and just bad treatment of other human beings gets patterned into our genetic makeup. Without today's generations having experienced it, it gets awakened by any traumatic event. It's like the memory is in our blood, in our genes. And when we meet a traumatic experience, we remember and we react as if we are the ones who have just been enslaved, or just been tortured. That pain endures from generation to generation, unless, as you say in my continent, or in my country, it is ritualized into a healing process.

CURWOOD: Dr. Ramphele, you are perhaps one of the world's most famous widows, if I can put it that way. The father of your children was Steve Biko, one of the leaders of the Soweto uprising that began in 1976. He was killed viciously by the police the next year. How did the uprising in Soweto, which of course was key to the change in South Africa, how did this embody Ubuntu?

RAMPHELE: Well, the uprising in Soweto was actually not led by Steve or any of my generation. What we did was to inspire young people to believe in themselves through the black consciousness movement. And that movement was simply saying: you are a beloved creature of God. No one has a right because of the color of your skin to treat you any less than you should be treated. But you have the power to not allow what other people think about you to govern you. And it is a free mind that is the first step to freedom. So you can be able to say "no" to your oppressor. And that's what happened with those young people in Soweto. Now, how does that tie up with Ubuntu? Of course, when we say I am black, and I'm proud, we are saying everybody, whatever the color, what matters is that you are human. We gave up on mimicry, and went back to our roots, re-embraced Ubuntu and allowed that to be a new way of being.

CURWOOD: So the principles of Ubuntu of course need to translate by culture to culture. How do you think Americans could adapt the principles of Ubuntu to our own problems?

RAMPHELE: The principles of Ubuntu are there in many cultures, and in many languages, you don't have to call it that. But what you have to do is to recognize that deep down in all of you is that inextricable connectedness. Seminal moments in your history in the USA, they were when you got together. Whether it's the March on Washington, or even sad occasions where you were burying your heroes. But also, when you celebrate the coming into office of a new president, that's when the highest positive energy is in your country. Let's learn from that.

CURWOOD: We've seen the beginning of the arrival of a set of vaccines that will allow humanity to better combat this pandemic. But of course, addressing the disease is only part of truly healing. What should the world be doing now to take advantage of how COVID has shown how perilous the human condition is, with our present set of behaviors?

The New Possible: Visions of Our World Beyond Crisis is a collection of 28 essays, including Mamphela Ramphele’s essay on Ubuntu. (Photo: Courtesy of Cascade Books)

RAMPHELE: I think COVID has opened our eyes to [the fact that] we cannot be healed, we cannot be well, unless the ecosystem in which we are in, including the human community, is well. What the vaccine does is to give us a little break and an opportunity for those who are particularly the frontline workers to be able to help those who are already affected. But for the rest of us, if we get immunity is not the end of COVID. What scientists say is that we are likely to see more and more of these break-ins from viruses that we have opened up their ecosystems by destroying the forest. We know that human beings and their immune systems function best when they feel loved, affirmed, and even in the poverty of material things. And so we now have an opportunity to reimagine a world where we see ourselves as part of nature. We are not saving nature, nature will save itself. We have to save ourselves from this existential crisis by changing fundamentally the way we live, how we relate to one another, and how we relate to the rest of life. And that's the opportunity we have.

CURWOOD: So before you go, Dr. Ramphele, what words of comfort or advice do you have for those of us who are the most vulnerable as the flames from COVID still rage?

RAMPHELE: First thing to remember is that we are in this together, and you are not alone. You may feel alone, but you are not alone. Your ancestors are with you. And those who are yet to be born from your line are with you. Second, you are valuable. You are important because you are such a unique creature, and your Creator is with you. Third, you have the ability to do what it takes to meet these challenges of today by stretching your hand across the fence to your neighbor to others around you so that you can lend a hand and they'll lend a hand. It is when we work together as families, as neighbors, as people working together, as nations, and as a global community that we actually get to overcome.

CURWOOD: South African physician and activist Mamphela Ramphele. Her essay on Ubuntu is in the book, The New Possible.

Related links:

- Click here for The New Possible book (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- TED Blog | “I Am, Because Of You: Further Reading on Ubuntu”

- Mamphela Ramphele’s website

- TIME | “Soweto Uprising | 100 Photographs”

- Find other great books featured by LOE on Bookshop.org (Note: This is an affiliate link)

[MUSIC: John Williams and Friends, “Township Kwela” on The Magic Box, by Timothy Walker, Sony Classical]

Coming up –From religious symbols to manicures the many surprising ways insects feature in our daily lives.

Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[MUSIC: John Williams and Friends, “Township Kwela” on The Magic Box, by Timothy Walker, Sony Classical]

BirdNote®: Insects Are Essential

A white-eyed Vireo grasps a caterpillar in its beak. (Photo: Kelly Colgan Azar, CC)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood

[BIRD NOTE THEME]

CURWOOD: This time of year many of us may be cursing the bugs that bite. But as BirdNote’s Mary McCann reports, our tormentors are a delight for birds.

BirdNote®

Insects Are Essential

Written by Bob Sundstrom

This is BirdNote.

[Wood Thrush song in background, followed by Nashville Warbler song, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/250158611#_ga=2.263181902.313880498.1…, 0.00-04]

MCCANN:A tiny Nashville Warbler flies to its nest, a fat caterpillar clamped in its beak. Nearly all of North America’s smaller birds, from this warbler to chickadees to thrushes, raise their young on insects—especially insect larvae like this juicy caterpillar.

[Rose-breasted Grosbeak song, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/248683961#_ga=2.121617544.1090204237…, 0.30-.34]

MCCANN:Insects sustain our ecosystems, and not just as a food source. They also pollinate 90% of all plants. And without plants at the heart of the food web, life on earth would simply collapse. As naturalist E.O. Wilson put it, insects are “the little things that run the world.”

Though insects are small, easily overlooked, and often vilified, most are beneficial. But their numbers have dropped by half in the last 50 years, so it’s now critical to help foster insects. One concrete way to help is to grow native plants that provide food and shelter for insects like caterpillars.

For example, in the Eastern United States and Midwest, buttonbush supports 18 different species of caterpillars and also provides food for birds in the form of nectar and seeds.

Growing such plants directly benefits birds and helps insects keep the natural world ticking.

Contact a local Master Gardener to help you find what’s best for your area. Begin at BirdNote.org.

I’m Mary McCann.

[Rose-breasted Grosbeak song, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/248683961#_ga=2.121617544.1090204237…, 0.30-.34]

Senior Producer: John Kessler

Production Manager: Allison Wilson

Producer: Mark Bramhill

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Nashville Warbler ML 250158611 M Medler

Rose-breasted Grosbeak ML 248683961 J McGowan

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2021 BirdNote March 2021 Narrator: Mary McCann

ID# garden-13-2021-03-16 garden-13

[primary source is Douglas W. Tallamy, Nature’s Best Hope. Timber Press, 2019]

[quote from E.O. Wilson, “The Little Things That Run the World.” Conservation Biology 1 (4); 344-46]

Resources:

https://www.nwf.org/Garden-for-Wildlife/About/Native-Plants

https://www.audubon.org/PLANTSFORBIRDS

CURWOOD: For photos buzz on over to the Living on Earth website, loe dot org.

Related link:

Listen to this story on the BirdNote® website

[MUSIC: Dr. Lonnie Smith, David “Fathead” Newman “Tropicalia” on Boogaloo to Beck, Scufflin’ Records 2003]

The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World

There are around 10 quintillion insects on the planet, says Edward D. Melillo, author of The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World. (Photo: Phil Fiddyment, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: There are some 800,000 known species of insects, and surely many more not yet discovered. Many of us may not realize it but insects actually play a critical role in our daily lives. Insects pollinate our crops, of course, they’re also used to make our apples shiny, our wood waterproof, and some candy just the right shade of red. In his book, Butterfly Effect, Insects and the Making of the Modern World, Edward Melillo takes a deep dive into the surprising history of human-insect relationships and how they have evolved and endured over time. Ted, welcome to Living on Earth!

MELILLO: Thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: Well, the first chapter of your book is full of interesting, bizarre kind of disturbing, fun facts about insects. Can you give us a couple of your favorites?

MELILLO: Sure. So one of my favorites is that there are 10 quintillion insects living on the planet. And it's 10 followed by 18 zeros. But it just goes to show that we're radically outnumbered by insects. And really, in a lot of ways, this is an insect planet that we're just happening to live upon at this moment. And insects are governing all the basic processes that make life possible from plant sex to decay and all sorts of other crucial ecosystem services that didn't insects are responsible for.

BASCOMB: You talked about a study that found some 10,000 species, not individual, but species found in the average North Carolina home. That was shocking [LAUGHS] I don't think it's just North Carolina.

MELILLO: Yeah, it was a study led by an entomologist named Michelle Trautwein from San Francisco. And she and her team of investigators went into houses in North Carolina and they also did another study where they looked at everything from parisian apartments to high mountain huts in Peru, and insects were just everywhere, all the time. And perhaps we don't notice them because they're doing a lot of their work between blades of grass, and under garbage cans and refrigerators but they're, they're doing really important work behind the scenes. And as I show in the book also, they're on our bodies, they're in our food. They're in our pharmaceuticals, and they're really in a lot of ways hosts of what a future planet might look like too.

BASCOMB: You know, I was surprised to read about the role that some insects have played in certain religions. Can you give us a sense of that?

Silkworms are moth caterpillars. Their cocoons are made of a single strand of raw silk that is harvested and woven into smooth, shimmering silk fabric first invented in China thousands of years ago. (Photo: Baishiya_白石崖, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, most chapters of your book, take a deep dive on a certain insect. So let's talk about one the domestication of silkworms.

MELILLO: Yeah, it's totally fascinating. I talk in the book about the Chinese princess who 1000s of years ago, was sitting under a mulberry tree, sipping on a cup of tea, and apparently, a silkworm cocoon fell into her teacup she reached in and then she pulled it out, this long, 10 style thread came forth and stretched on and on and on, and it was remarkably strong. And she's considered among the Chinese to be the legendary founder of silk production. But today, we still depend upon billions and billions of tiny caterpillars. We call them silkworms, but they're really caterpillars for the production of our silk. And silk is extremely widely consumed. I mean, who hasn't felt or touched silk at some point. And it's a really, really fascinating story. But it also is a story about a resurgence of a product that seemed to have disappeared in the 1940s after the Second World War, as rayon and polyester seem to be taking over the world. But it turns out that silk has a lot of properties that are inimitable, and engineers have never figured out how to make fibers that have the same kind of strength and flexibility and properties that can reflect light in the ways that silk can. And so once again, many of the human substitutes for these insect secretions turned out to not hold all the promise that we were told they would.

BASCOMB: You talk about shellac in the second chapter of your book. Many listeners may be familiar with shellac. It's a wood varnish and may be used as a nail polish, but they probably don't realize that it actually comes from an insect. Can you tell us more about the bugs that produced shellac and how it's actually made?

MELILLO: Sure, sure. So shellac is the secretion of the female kerria lacca insect. And she lives on fig and acacia trees in India and parts of Southeast Asia, Thailand, southern China. This was the most surprising chapter for me because I knew so little about it. And then I came to learn that 78 RPM records which were basically the medium of the global transmission of sound up until the vinyl era and the 1940s are made out of an insect secretion and that really blew my mind. Female insects have the kerria lacca species secrete it to protect their young from ultraviolet radiation and predators, but then it's harvested by men and women in these regions of the world still today. Millions are employed this way. It's melted down and then turned into a hard substance and broken up into fragments. And it gets re-melted in other countries. And so that was mind boggling to go into the extraordinary array of steps that shellac takes to get, as you said, onto our back deck or fingernails. It's in a hair spray, you go to a grocery store and you buy a shiny apple. And that apple is kept shiny often by shellac, shellac is a an FDA approved coating for many foods. And it's also interior coating for many pills to keep medicines from dissolving too quickly in the highly acidic environment of the stomach. And so we're eating shellac, we're spraying it on our hair. We're putting it on our fingernails, but yet, hardly ever do we remark on the fact that it's an insect secretion that comes from a whole interesting array of locations a world away.

The cochineal is an insect that, when crushed and processed, creates carminic acid that is used to made carmine dye. Today this dye is used primarily to color food and lipstick. (Photo: Vahe Martirosyan, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: See right in your book that shellac is not the only insect produced substance that we're eating regularly. Another whole chapter you write about the coach cochineal, which people crush up to make a red dye in food coloring. Can you tell us more about them?

MELILLO: Sure. So like silk and shellac. The other two oddities I focus on in the book cochineal has an ancient history that goes way back to Peru's paracas culture. The Aztecs and Mayans produced cochineal. And we've got records of Montezuma, the second taking cochineal bags as tribute from his subjects. And the way it's made is again, it's the females who are doing all the work there's a theme here, the female insect bodies are crushed to produce this carmine red dye, and the insects are raised on nopal cacti they dine on the sweet juices inside of the cactus, and then the female raises her young surrounded by kind of a downy secretion, but then it takes about 70,000 female insect bodies to produce a one pound brick of dried cochineal dye. And when Europeans came across this 1500s, after the Spanish conquest of the Americas, they just couldn't get enough of it because it has tremendous fixative properties, it doesn't bleed away and it creates a whole host of brilliant colors. You can combine cochineal with mordants that are basically different types of metals to produce deep sort of Corinthian purple hues. And you can produce these really bright Scarlet reds. And of course for ecclesiastical vestments, and royal robes, Europeans wanted red the color for virility and Christ's blood. And so once they got their hands on this new source of red dye, it became the second most lucrative traded product in the Spanish Empire after only silver. And today, it's made a resurgence and is used as a safe food coloring for all sorts of things, from candy to fake crab legs to specialty cocktails, it's in everything sausages, you name it, it has cochineal. I mean, part of the reason for this is that many of the substitutes for these natural products that people came up with after the Second World War turned out to be toxic. So cochineal has made a comeback just like Sherlock and silk, in part because of the failures of substitution. And I talked about that quite extensively in the book.

BASCOMB: You know, for many Westerners, the idea of purposefully eating bugs can be you know, kind of off putting, but you're right that many people most people are actually already eating insects, and not just in cochineal and shellac, as we've talked about, but in a lot of other ways. Can you give us some examples?

MELILLO: Sure. So right now on the planet about 2 billion people on a regular basis, eat insects, it's just a part of their regular daily diet, almost every world culture some insect dish that's central to their food culture in Japan eating sasa-mochi, which are riverbed harvested larva is very common, bundongi in South Korea are silkworm pupa. I've eaten those and they taste a little like a cross between a peanut and a shrimp. I'd say it was strange but interesting new taste experience. In Mexico chapulines, fried crickets and grasshoppers, a wonderful snack actually really enjoy those. But we're all eating insects, you may not know it, but I'm drinking a cup of coffee, for example. And the United States allows about 10% of the green beans that are brought into this country, the insect body parts. And if drinking coffee or tea, you're most certainly consuming insects. It's in peanut butter and chocolate. The FDA allows insect body parts, there are quotas for both of those as well. So if you can do many of these products on a daily basis, you may not know it but you're consuming insects regularly.

BASCOMB: You know, you've always heard these stories of some bug crawling in your mouth while you're sleeping. But I guess it's a lot more subversive than that.

MELILLO: You know, it's it's totally a cultural thing, because, you know, just imagine, I teach many Chinese students and they think it's so strange that North Americans eat cereal with milk. That is just the most odd combination to them, yet it seems perfectly natural to us. So it's worth reminding ourselves that there's no biological basis for a distaste for insects. It's very culturally conditioned. And we're seeing a lot of indications that maybe this is changing in the United States, for example, at Safeco Field, the field where the Seattle Mariners play. They've got a restaurant there that's been serving up chapulines fried grasshoppers for years, and they're a best seller alongside popcorn, peanuts, and hot dogs. So, you know, this may be the harbinger of things to come. Who knows?

Many people in the world eat insects without realizing it. Coffee, cereals, produce, and other food products contain parts of insects unfortunate enough to be harvested along with the intended crop. (Photo: Popo le Chien, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

BASCOMB: Yeah, that's the thing. I mean, people talk about insects as being the protein source of the future. And I think it is cultural. I have a friend. She was in the Peace Corps back in the day and she was going to go back to her village in Niger. And she was really excited because she was going back during locusts season, which is a time when they capture the locusts, fire them up, throw some salt on them and you know, eat them like popcorn and she was really stoked to be going back at that time of year.It's something people enjoy.

MELILLO: Absolutely. And in many cultures, I mean much of Southern Africa eating mopane Caterpillar is called mopanes, is very common, and it's a multi million dollar industry that gives protein to people where refrigeration is scarce, it can be a really important alternative. And I'll just give you one statistic for your listeners to think about. In the United States to produce one pound of beef, it takes 1000 gallons of water and two acres of grazing land. To produce one pound of crickets. It takes one gallon of water and two cubic feet of space. And with the crickets, you get about three times the amount of protein, much more iron and nutrients. And essentially, these are freeze dried pulverized and turned into a high protein meal. I certainly think it's going to be part of the array of possible solutions for the future.

BASCOMB: Now, of course, perhaps the most well known and important insect for human beings is the bee. Honey bees give us honey and they pollinate on the order of one in every three bites of food. They're so important. Can you tell us a bit about the history of that relationship? And what's going wrong with it today?

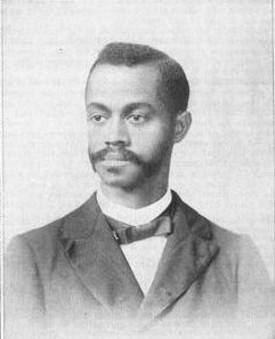

MELILLO: Yeah, so our understanding of pollination is a quite remarkable story in and of itself. And I delve into that quite a bit. One of the most fascinating characters that I came across when I was learning about how we came to know more about pollination was Charles Henry Turner. He was an African American biologist born at the end of the 19th century. And he was the first African American to get a PhD in zoology at the University of Chicago and the first African American to get published in the prestigious journal Science. Yet we know very little about him, he was unable to get a university job because he was black. And so he ended up teaching high school, he had no laboratory, no graduate students. And he did all of the pioneering work that led us to really understand how these are actually rational actors that make decisions and move about in this world not as sort of robotic beings but as free thinking individuals as part of social groups. And Turner's story I found truly amazing. Today, the real threats to bees, we talked about them as colony collapse disorder seem to be coming from a variety of sources. One of them though, and it's a big one, are a class of pesticides, known as neonicotinoids, or neonics. They're pesticides that mimic nicotine, which you may know of as as one of the chemical secretions of the tobacco plant. But these chemicals that mimic nicotine are really wreaking havoc on bee colonies, habitat destruction, climate change are big parts of it as well. But also there's a parasitic mite called the Varroa destructor. It's got a very vivid name that has been hurting bee colonies as well. But neonicotinoid this class of chemicals really needs to be banned. Because we depend so much on bees for our fundamental existence on this planet. And it's easy to forget how much we depend upon bees, the almond butter that you might put on a piece of toast in the morning that was all dependent upon bees as is your morning coffee, your tea, many of the vegetables you consume on a regular basis, avocados, broccoli, you name it.

BASCOMB: Well, Ted, what do you suggest for someone that maybe wants to learn more about insects on a personal level? You know, many of us are trapped at home right now with a virus and a captive audience for taking up a new hobby. I don't know what do you think of an ant farmer, any other ideas that you might have?

Charles Henry Turner was a pioneering zoologist who studied the behavior of bees. (Photo: Unknown Photographer, Project Gutenberg, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

MELILLO: Yeah, so I've been raising silkworms, with my seven year old and we've had a remarkable time doing that. We purchased online for about $10 a bunch of little eggs, they showed up in a petri dish there were about 250 of them, they like little poppy seeds. And we put them in a styrofoam chicken incubator which cost us another $10 or so to keep them nice and cozy. And they hatched and we've been watching them grow you have to feed them a lot because they eat about 10 times a day. And it's remarkable to see them growing in front of your very eyes, but it also suggests Just really helping kids become attentive to insects in their lives in other ways, maybe then lice or ticks. You can listen to a crickets chirps for example. And if you do that for 14 seconds, and that add 40 to that number, you'll get a remarkably accurate reading of the temperature in degrees Fahrenheit outdoors. And that's because crickets are exothermic and they respond to the ambient temperature. And they slow down when it's cold and go faster when it's warm. And we tried it with our porch thermometer and every time we got within one or two degrees of an accurate temperature reading by simply listening to the crickets outdoors, so I hope the book in some ways and my work in general creates more attentiveness to what insects are trying to tell us both literally and figuratively about the health of our planet.

BASCOMB: Ted Melillo is a professor of history and Environmental Studies at Amherst College and author of the new book, The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World. Ted, thank you so much for all of these bug stories.

MELILLO: Thanks for talking with me. I really enjoyed it.

Related links:

- Click here for more on The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- National Geographic | “Five Vital Roles Insects Play in Our Ecosystem”

- The Old Farmers’ Almanac | “Predict the Temperature with Cricket Chirps!”

[MUSIC: Bill Tyers, “When You Wish Upon a Star” unreleased, by Leigh Harline and Ned Washington, Guitar Downunder]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Anna Canny, Jenni Doering Jay Feinstein, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Joshua Siracusa, and Tivara Tanudjaja and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to the Stuart B. McKinney Wildlife Refuge. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth