August 13, 2021

Air Date: August 13, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

California Tree Deaths Could Hurt Forests on the East Coast

View the page for this story

Research shows that tree deaths in California can hinder plant growth all the way across the continent in Eastern North America. Abigail Swann from the University of Washington explains to Host Steve Curwood how tree deaths cause changes in atmospheric moisture and impact local climates thousands of miles away. (07:59)

BirdNote®: Eastern Wood-Pewee

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

The Eastern Wood-Pewee is inconspicuous, but its plaintive whistle is unmistakable in the woodlands of east North America. As forests have declined so have the Pewee, and BirdNote®’s Mary McCann reports that wildlife managers are now trying to save this iconic voice. (01:56)

Ancient Underwater Forest in the Gulf of Mexico

View the page for this story

Sixty feet beneath the waters off the Gulf coast of Alabama lies a forest of cypress stumps more than 50,000 years old. Ben Raines tells Host Steve Curwood what it’s like to scuba dive among the remains of ancient trees. (08:04)

'Forest Bathing' for Health

/ Kara HolsoppleView the page for this story

A walk in the woods might be just what your health provider ordered. Numerous studies suggest that taking in the peaceful atmosphere of a forest can have significant health benefits. Now the practice of “forest bathing,” which originated in Japan in the 1980s as a form of nature therapy, is becoming more popular around the world. From a forested Pittsburgh park, Kara Holsopple reports on this practice for the Allegheny Front. (06:02)

Bottlenose Whales in the Arctic

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender describes a pod of bottlenose whales as they swim through Hudson Strait above the Arctic Circle, and his impulse to join them. (02:36)

Journeys North: The Pacific Crest Trail

View the page for this story

In a typical year, several hundred intrepid hikers walk all the way from Mexico to Canada, along the Pacific Crest Trail. At more than twenty-six hundred miles long, it covers some of the most challenging and spectacular terrain in North America. But it’s not just about the pretty scenery, writes Barney Scout Mann in his book Journeys North: The Pacific Crest Trail. He joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about braving blizzards, bears and blisters, and the tight-knit community he and his wife Sandy found on their PCT hike. (19:21)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

210813 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Abigail Swann, Mary McCann, Ben Raines, Moshe Sherman, Barney Scout Mann

REPORTERS: Mark Seth Lender, Kara Holsopple

CURWOOD: From PRX this is Living on Earth

(THEME)

I’m Steve Curwood

In the spirit of loving the outdoors and biophilia we look to the Japanese tradition of forest bathing as a tool for staying healthy.

SHERMAN: If you do one session of forest bathing for even 20 minutes we see an increase in the NK cells or the natural killer cells and these are the cells that protect us from viruses and even from tumor formations.

Also, the culture of long distance hiking - from trail names to trail magic.

MANN: Trail magic is any act to kindness toward a hiker. Whether you have a bit of your town lunch left over. You’ve gone out on a day hike and you run into a longer distance hiker and you see them eyeing that piece of pizza you’re just planning on taking home and throwing away and you give it to them. And you just made their day. That’s trail magic and you who have done that is a trail angel.

That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

California Tree Deaths Could Hurt Forests on the East Coast

Drought-killed trees killed in California, pictured in 2016. (Photo: Nathan Stephenson, USGS)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanely studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston this is an encore edition of Living on Earth.

I’m Steve Curwood.

Since 2010 more than 120 million trees have died in California alone. Bark beetles, drought, and wildfires are largely to blame and according to forest modeling research those tree deaths in California can have big impacts on other parts of the country, as far away as the East Coast. University of Washington Professor Abigail Swann published her research in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

SWANN: We looked at a bunch of regions in the US. And we've looked at what would happen if forests were removed in those regions. And these are regions that the National Science Foundation has identified as sort of eco-regions. And we took each of these ones that had a lot of forest cover in them, and we said, What would happen if those forests were gone? So it turns out that plants are able to influence the atmosphere around them, so they can influence the local climate that's experienced nearby, but that the atmosphere, because it is circulating around, is moving, those local changes, they can get communicated to other places. And so changes in plants in one location can actually have impacts on the climate somewhere else. And that can also impact the plants somewhere else. Because plants are influenced by the climate that they're experiencing. We found that the location of the forests really matter. So in general, losing tree cover in the West, particularly in areas like California had bigger negative impacts, meaning it, it led to less plant growth across the continental US. But there were some places where removing trees led to more plant growth across the US in general.

CURWOOD: So what makes a difference?

SWANN: It's really the location of where those plants are, and how they're able to influence the atmosphere and what changes in climate that leads to, that plants care about. So what we found is that in general, plants grew more when the summers were a little bit cooler and a little bit wetter. And so if forest loss led to hotter summers, or drier summers, then we saw less benefit for plants in general.

CURWOOD: How exactly does that work? I imagine it's related to evaporation, among other things.

SWANN: Right well, the local surface temperatures care a lot about how much water gets evaporated. So in general, when water is able to evaporate off the surface, you'll get less change in temperature. So your skin, when water evaporates off your skin, when you sweat, it helps keep you cool. If there isn't as much water available, the surface is likely to get warmer. And so that influences the local temperatures. The reason the atmosphere can sort of propagate that signal elsewhere is because it's essentially, you know, the atmosphere is a big fluid. And so waves and other things propagate in the atmosphere. And that signal can be transmitted somewhere else where it then has some impact on climate. The really classic example of this would be like an El Niño. So we're all pretty comfortable with the idea that this thing called El Niño influences climate in places in North America. But it's actually a big sloshing around of temperature in the tropical Pacific Ocean. And so that big sort of oscillation in temperature in the tropics influences the atmosphere, kind of like dropping a rock in the pond. And that signal propagates to North America where it then influences temperature or rainfall over different parts of the US.

CURWOOD: So what you're saying is, if you lose a bunch of trees in California, it's like dropping a rock into this fluid we call the atmosphere, and the ripple will come out east and it'll have effect on trees there?

SWANN: That's the idea. And our hypothesis, based on these simulations, is that that impact is generally bad for plants across the eastern US.

CURWOOD: And remind us of what's driving the tree loss to begin with in the West.

SWANN: Right. So the tree last that we are seeing across California has really been driven by an extreme drought over the last few years. So it's been very dry. And I think the Forest Service has estimated about 120 million trees have died due to these really harsh conditions of low water and high temperature. And so there, there has been pretty significant tree death occurring across California just in the last couple of years. But more extensively across the western US in the last decades, we've seen a lot of trees that have died due to beetle outbreaks and other pest problems.

Wildfires in the forests of the American West are becoming more frequent and, in California, they took a devastating toll on lives and property in 2018. (Photo: NASA Earth Observatory)

CURWOOD: A couple of decades ago, people looking at how much carbon was going into the atmosphere from North America were doing a happy dance about all the trees that had come back in the East that had been cut down, during the farming in the 1800s. And now this area, especially Adirondacks, is afforested, you guys would say, and that this was sucking a lot more carbon out of the atmosphere. What you're telling me is that, well, wait a second, those trees may not be in such a great position now to remove carbon given what's happening out West.

SWANN: Well, that's possible, right? And this is one of the big uncertainties of how much carbon the whole land system will be able to store going forward is, you know, we there has been an uptake of carbon by those forests, as they regrew. But I think it's very uncertain what that will look like, as we go into the future -- either in North America, or really anywhere else on the globe. There's things about changing climate that will help plants grow better, like increasing temperatures in places that were colder; higher levels of carbon dioxide help plants grow a little bit more. But if they become more water stressed or if it leads to more plant death, that could be really bad. And this is a huge open question in our scientific field that we really don't know the answer to yet.

CURWOOD: So Abby, you study atmospheric science and biology. Sometimes you scientists say that our present time, or up until recently, anyway, we were in a fairly stable what you call an interglacial period, that things were staying pretty much the same. To what extent does your research suggest that well, things really aren't so much the same anymore?

SWANN: Right? Well, I'd say climate change in general, is pushing us very strongly out of that stable environment that we've been in in the past. And as you mentioned, climate change can lead to more stress on trees, that can lead to more tree loss. And we think that in a specific example of our own research, that this would have these larger scale impacts. In general, I think if we think about land systems and plants and how they grow, there's a lot of unknowns about what tipping points might exist. If you think about a system like the Amazon forest, and is it vulnerable to change? What will that system look like in the future under a much hotter climate? We have no examples on Earth right now to compare that to. There aren't places that are hotter than the Amazon but also wet, so we have no place to look to see what that might be like. And so there's a lot of work to do from a scientific standpoint, to try to understand that. But also, I think it's important to say that we don't understand yet, but the potential is scary.

CURWOOD: A number of years ago, the Met Office, that is the UK weather and climate modeling group, said that by the year 2050, the Amazon really could just be a grassland. What do you make of that research? And given your research, what might that tell us? Or what might that warn us?

Forest loss in California could hinder the growth of trees and other plants on the East Coast. Here, a Vermont forest in the midst of its colorful autumn transformation. (Photo: Brad Fickeisen on Unsplash)

SWANN: Right, so there's been a lot of work since the original findings came out. And I think that we understand a lot more about what some of the limitations were of those original studies. But the sort of premise still exists that the Amazon will be experiencing a very unseen climate – or, unseen in any sort of human timescales. Maybe if we go back to the time of dinosaurs, there were temperatures that were that high, but that this is a really new or novel climate that the Amazon will be experiencing. And there's a real question as to what that forest will look like. I think there's less of a thought that it would collapse completely into a grassland, but still a lot of questions of if it will be able to maintain as many trees, or as high of a biomass, or as high of a biodiversity as it does now.

CURWOOD: Abigail Swann is an Associate Professor in the Departments of Atmospheric Sciences and Biology at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Related links:

- Read the journal article published in Environmental Research Letters

- About Abigail Swann’s Ecoclimate Lab at the University of Washington

[BIRDNOTE® THEME]

BirdNote®: Eastern Wood-Pewee

Eastern Wood-Pewee (Photo: CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well one of the many animals that makes its home in the Eastern forests we’ve been hearing about is the Eastern Wood-Pewee. And as Birdnote’s Mary McCann reports the once common woodland flycatcher is now a species of concern.

http://birdnote.org/show/eastern-wood-pewee-and-eastern-deciduous-forest

BirdNote®

Eastern Wood-Pewee and Eastern Deciduous Forests

[Slurred, whistled “pee-ah-wee” of Eastern Wood-Pewee; repeat]

MCCANN: Each year, by mid-May, a plaintive, whistled song carries through the forests of eastern North America. It is the voice of the Eastern Wood-Pewee, returned to nest after a winter sojourn in South America.

[“Pee-ah-wee” of Eastern Wood-Pewee]

(Photo: Greg Lavaty)

An Eastern Wood-Pewee perches inconspicuously in the shady interior of the forest. Inconspicuous, that is, until it sallies out to snatch a flying insect. Or until it offers up that unmistakable song.

[“Pee-ah-wee” of Eastern Wood-Pewee]

But for the past 25 years, the number of Eastern Wood-Pewees has fallen, across much of the bird’s range. How is it that even a once-common bird can decline so steadily? Fragmentation of forests into ever smaller tracts, as well as forest disturbance — such as heavy browsing by overabundant White-tailed Deer — are part of the problem. So is the loss of forest in the bird’s South American winter range. As a result, the Eastern Wood-Pewee is now a species of high conservation concern.

[“Pee-ah-wee” of Eastern Wood-Pewee]

What practices can help stem the decline of Eastern Wood-Pewees and other forest birds? Well, providing economic incentives for private landowners who save forests is one. Enacting policies that promote smart growth and curb urban sprawl is another.

[“Pee-ah-wee” of Eastern Wood-Pewee]

###

I’m Mary McCann.

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Call of the Eastern Wood-Pewee provided by The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York and recorded by G.A. Keller LNS 73930. The fly was recorded by G.F. Budney. Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2010/2016 Tune In to Nature.org Narrator: Mary McCann

http://birdnote.org/show/eastern-wood-pewee-and-eastern-deciduous-forest

CURWOOD: There are pictures fled on over to the LOE website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Listen to the original story on the BirdNote® website

- BirdNote®

[MUSIC: JPP, “Tango Bonito,” Devil’s Polska, Hans Lankari, Green Linnet/Xenophile

CURWOOD: Coming up – a forest from 50,000 years ago emerges underwater in the Gulf of Mexico. That's next on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at SailorsForTheSea.org.

MUSIC: Harvey Reid, “Wayfaring Stranger,” Dreamer or Believer, traditional Appalachian, Woodpecker Records]

Ancient Underwater Forest in the Gulf of Mexico

This cypress wood is over 50,000 years old (photo: Ben Raines/Alabama Press Register)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood

And now let's head under the sea in search of a long-lost forest. Deep beneath the surface of the Gulf of Mexico, off the Alabama coast, lie ancient cypress trees that only a handful of people have ever seen. One of those lucky few is Ben Raines, director of the Weeks Bay Foundation* and he explained how it all came about.

RAINES: For many years I was the environment reporter for the paper down here, The Press-Register, and so I had a buddy who owned a scuba diving shop, and he used to taunt me with this tale of an underwater forest that he had been diving on one time, and I pestered him for years and years and years, and he finally agreed to take me out there.

He heard about it from a fisherman who just noticed a ledge on his bottom machine as he was riding across the gulf. So he started fishing there and catching a lot of Red Snapper. And he gave the numbers, the GPS coordinates, to my buddy that owns the dive shop and asked him to go out there and see what it was. He hit the bottom and said there’s a bunch of trees.

CURWOOD: Now how deep is deep for an underwater forest?

RAINES: Well, this is about 60 feet. Of course, all over the Earth, we know sea levels have gone down hundreds of feet. So we have a delta, a river delta here. Further up in the delta, about 80 miles inland, there’s sand dollars all over in these limestone bluffs. So we know sea level was that high at one time. Now we’ve got these trees 60 feet underwater, so sea level was that low, and it’s just a fascinating push and pull of the ocean through the climatic change over the eons.

Ben Raines, executive director of the South Alabama Land Trust (Photo: South Alabama Land Trust)

CURWOOD: So when did you finally get to visit the forest?

RAINES: I got out there a year ago last August. We went out...the first trip we tried to go out, the boat broke down. The second trip, the boat broke down.

CURWOOD: Of course. Boats always break down, don’t they?

RAINES: [LAUGHS] Absolutely. Especially my boats.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

RAINES: So we finally made it out there and the way we dive here, we’ll drop the anchor over whatever the GPS number is. And then we swim down the anchor line to get to the spot because the water’s a little murky - otherwise you get lost. I went down the anchor line, and when I hit the bottom, there it was. The first stump. And it was about as big around as a garbage can lid, but it had that very distinctive irregular shape that a Cypress trunk has….

CURWOOD: Uh-huh.

RAINES: …and then it was surrounded by knees. You know, Cypress trees have knees - you see them in the swamps - that stick up out of the water to kind of help hold them in place, and here was a Cypress tree on the bottom of the ocean. And I swam a few feet, and there was another one, and a few feet more, another one, and I quickly realized they were all around me in every direction.

The trees have created new habitat for fish and other marine life (photo: Ben Raines/Alabama Press Register)

CURWOOD: Wow. I mean, this sounds almost magical down there.

RAINES: It is absolutely magical. It’s totally enchanting. You know, these trees are covered in anemones and crabs and shrimp - and then you have these huge clouds of Red Snapper and Grouper following you around. I was down there one day swimming along the ledge where the biggest stumps are, and I turned around and there was this huge funnel shape of fish behind me, I mean it must have been 200 Snapper, and they were just following me around. When I stopped, they would stop. When I turned around, they all fell in behind me.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] What about the Groupers? They’re very social.

RAINES: Oh, yes. They’ll come right up to you. And some of the fish that are down there, the trigger fish, will actually come up and chew on your camera. You have to shoo them away. They just seem to have no fear.

Fish hide in and among the roots of the trees (photo: Ben Raines/Alabama Press Register)

CURWOOD: You must have had a lot of fun because we saw this video that you made of your dive down there, and we’ll put it on our website. But have you experienced anything like that before?

RAINES: You know, I never had. I’ve been diving for some time, and from the moment I hit the bottom and saw the stumps, it was just exhilarating. You knew you were in this sort of “land of the lost”, this place that shouldn’t exist, but here it was, and I got the camera out, I hit the record button, and I never turned it off, and that’s exactly what I’ve done every dive I’ve made down there. And now I’ve been going down there with three cameras, you know, setting them up in different locations just to kind of capture this place while it’s there, because if we get a storm, it could theoretically come into the Gulf and change everything out there and bury this place up again. You know, it may be a very ephemeral place. We may only get to see it for a little while.

CURWOOD: So how old do scientists think these trees are?

RAINES: Well, I brought a few samples up, and I actually took a hand saw down there with me and cut them just like you’d cut a tree in your backyard. So I cut some sections out of them, gave them to Christine DeLong at LSU, and she had them radio carbon dated, and they had to do them three times in all I think because they didn’t believe the results. So they expected them to be 12,000 years old, which was the last ice age. Instead they came back radio carbon dead each time they tested them, which means they’re 50,000 years old or longer. So if we can...we want to get cores out of them, and then they’ll be able to count the rings and look at growth, and measure carbon inside them, things like that, and learn a lot about the past climate. We had another team come out from University of Southern Mississippi, and we had them do a sonar survey so we could try and get an extent of it because I’ve only been swimming around 300 yards of it. It turns out it’s spread close to a mile; it’s much larger than we thought, and there appear to be some much bigger stumps. I’m due to go over there next week again and see what we can - what we can ground truth some of those other locations, or sea floor truth them, I guess.

One of the many cypress stumps (photo: Ben Raines/Alabama Press Register)

CURWOOD: Hey, Ben, how did this happen? I mean, how could these trees be preserved for so long?

RAINES: Well, any time in the ocean or anywhere else you’re able to get oxygen out of the mix, you stop decomposition. All those little bacteria and things that decay - cause decay - need oxygen, and so buried under six inches, eight inches of sand, you get into this anoxic layer where there’s no more oxygen. So these trees were covered up. We think Hurricane Katrina came through and dug this trench where the trees are now exposed, and so on the top layer of them, of the stumps, that top layer you can break it apart with your fingers - you know it’s very soft, and there’s all kinds of boring organisms digging holes in them. But once you get inside about a half-inch or an inch, then the wood’s very hard, and it’s like cutting a tree down - a living tree. And in fact, with the samples I brought up, when you cut them up in the dry air, you actually smell the smell of the sap just like you were cutting a fresh Cypress tree down. It’s really remarkable.

CURWOOD: Now that these trees have been uncovered, how will they survive?

RAINES: Well, they won’t. Ultimately, they’ll decay just like any wood that’s been sitting on the bottom of the gulf. The fact that they’re Cypress, gives them a little more longevity than other wood. Cypress is a very tough, rot-resistant wood, and for that reason, people love to make boats out of it. So, I don’t know how many years they’ll last. I can tell they’re decaying. I’ve been visiting it now for a year. And so I’ve got all these groups and companies calling me wanting to mine the logs. There’s a phenomenon called “sinker logs” where old Cypress trees that were actually so dense they couldn’t float would sink to the bottom of rivers, and there are companies now that go around and salvage these things, and they’re worth quite a lot of money. So here we’ve got the ultimate sinker logs, you know, 50,000 year old wood. So my goal is to have the place preserved before the numbers get out - the GPS numbers - so that people can go dive there, but I want it protected so they can’t go carve up the logs. I don’t want Fender and Gibson to get ahold of them and start making 50,000 year old guitars or 50,000 year old coffee tables. I’d like to see this preserved and in this enchanted little environment where people can enjoy it.

CURWOOD: We first aired this story back in 2012 and the fight to protect Alabama’s underwater forest from business interests continues. Scientists and advocates have asked the Biden administration to designate the site a marine sanctuary.

*Editor’s Note: The Weeks Bay Foundation is now South Alabama Land Trust.

Related links:

- Check out Ben's documentary about the cypress forest

- Read Ben’s original story on the underwater forest

- Read Ben’s op-ed in the NYT about cleaning up the gulf

- Website for the South Alabama Land Trust

[MUSIC: Catch & Release - Matt Simons [Cover] by Julien Mueller & Lina Brockhoff]

'Forest Bathing' for Health

Studies show that 'forest bathing', or shinrin-yoku as it is known in Japan, appears to have health benefits. (Photo: Jordan Sanchez on Unsplash)

CURWOOD: Call it biophilia, love of the outdoors or simply common sense, research shows that spending time in nature can improve human health. In fact, the Japanese have a tradition known as shinrin-yoku or forest bathing, in which practitioners spend meditative time breathing in nature. Allegheny Front reporter, Kara Holsopple, went to Frick Park in Pittsburg to meet up with Moshe Sherman, a medical Qi Gong therapist who leads regular forest bathing outings.

SHERMAN: The first bathing started in Japan in the 80s as a form of preventative health care. And the idea is that in order to balance the stress of urban life, we need to expose ourselves to nature. And it's very simple. In fact, to just get yourself into nature and be present.

HOLSOPPLE: How is it different than taking a walk or hiking?

SHERMAN: Well, we don't have a destination in mind. And we don't rush just like when we take a bath in hot water, we settle in and relax, we can talk but it's not a time to talk about work like we might do during a walk with a friend or to complain about relationships. It's more time to go inward.

HOLSOPPLE: You're looking up.

SHERMAN: Yes, when we first bathe, we want to look all around and just take it in. So we breathe in the healing energy. We also bring it in through our eyes, we bring it in through our ears, hearing the sounds we bring in through feeling whether it's feeling the weather or touching a leaf. In Japan the term for forest bathing is shinrin-yoku and that literally means to bring in the forest.

HOLSOPPLE: Bring it in to yourself.

SHERMAN: Exactly, in the urban environment we often have to put up what I call energetic shields to protect us. I love cities. I've grown up in the city live in a city my whole life, but I can feel when I come into the forest. It's a chance for those shields to come down.

HOLSOPPLE: Even the muds kind of a soothing sound.

Moshe Sherman is a medical QiGong therapist who leads forest bathing sessions in Pennsylvania parks. (Photo: Kara Holsopple)

SHERMAN: Yes, it is. I was just listening to that as well. Each session is different. There was one session where we did a really fun exercise. We all put our hands on the same tree. And we did a guided meditation where we pretended we were squirrels running up the tree and we got to the top of the tree, looked around and ran back down. And at first I was wondering if anyone was there with me, if it's just me. I got some good feedback afterwards it was a lot of fun.

One of the nice things about forest bathing is it has been widely researched mostly in Asia and also in Europe. And what brought the most recent attention to the United States is a review that was published in summer of 2017 that looked at 64 of those research studies which are all based on empirical evidence, and it really impacts so many systems of the body, cardiovascular system, the respiratory system, and most profoundly, I think, to me right now is how it impacts the immune system. If you do one session of forest bathing for even 20 minutes, we see an increase in what's called the NK cells are the natural killer cells. And these are the cells that protect us from viruses and even from tumor formations.

HOLSOPPLE: Is it just the healing power of nature or something else going on? You know, like, what about being in nature is so good for us?

SHERMAN: There's many levels to it, I don't claim to understand them all. Trees emit something called phytoncides. And these are organic compounds that are released by trees to protect the trees themselves from parasites, disease, and they're actually beneficial for human health as well. So when we're around trees, and we're around plant life, we're breathing those in. I work with Chi or energy, which is a little more abstract, but I think of each tree and each plant as being a unique life form with its own consciousness. And I think when we expose ourselves to a variety of different life forms, it benefits us and I like to think of benefits trees as well, so I think it's a friendship.

Forest bathing advocates say even just a few minutes in a forest can help change your energy and mood. (Photo: Arnaud Mesureur on Unsplash)

HOLSOPPLE: What do people report to you? What do they say afterwards about the experience?

SHERMAN: Lots of times....

HOLSOPPLE: Does anybody hate it?

SHERMAN: No, I've never had anyone hate, or being unsatisfied, people usually feel more relaxed, more present. And really, when you start to talk to people, you realize that they're processing some heavy stuff that they're going through in their lives, and it helps them with that. People report feeling overall, better is the general feeling you get. I feel great people are chatty, which is always a good sign after a healing session or after a group event, when people feel chatty, it means the energies flowing it means they're feeling uplifted and feeling open to sharing and receiving.

HOLSOPPLE: I'm glad I didn't cancel.

SHERMAN: Me too. Yeah, this is great. You can feel the benefits almost immediately. And then notice how they last, they last with you. Lots of times I'll feel them wearing off and that's when I'll get myself back to the park back to the forest. Once you learn how to forest bathe you can do it anytime you don't need a guide although it's more fun when you come do it with a group, but you can do it yourself once you know how to do it. So it's it's like that saying, you know, give a person a fish they eat for a day, teach them how to fish they can eat forever. I think forest bathing is so essential to modern life and creating a balance and health in the modern environment.

CURWOOD: Kara Holsopple’s report comes to us courtesy of The Allegheny Front. And by the way, Moshe Sherman says if you are in a crunch for time, simply sitting under a tree for a while can change your energy and mood.

Related links:

- This story on the Allegheny Front website

- The New York Times | “Take A Walk in the Woods. Doctor’s Orders.”

- A meta-analysis of the potential health benefits of spending time outdoors

- About how phytoncides may promote better health

- Cloud Gate Pittsburgh

[MUSIC: The Beatles “ Within you Without You” demo recording 1967

Coming up – Thru-hiking twenty-six hundred miles on the Pacific Crest Trail. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: You can hear our program anytime on our website or get an audio download. The address is LOE dot org, That’s LOE.org. There you can also find pictures and more information about our stories. And we’d like to hear from you, reach us at comments@LOE.org, once again comments@LOE.org. Our postal address is post office box #990007 Boston MA 02119. Call our listener line anytime at 617-287-4121, that’s 617-287-4121.

MUSIC: The Beatles “ Within you Without You” demo recording 1967]

Bottlenose Whales in the Arctic

A bottlenose whale peeks out. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Life on earth likely began in the primordial soup of the ancient ocean. And humans still carry that original home in our bodies. The salinity in the plasma of our blood is remarkably similar to that of the ocean for example. And in a way, Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender says he longs to return.

Conferatur

A Pod of Bottlenose Whales

Hudson Strait

© 2020 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

From the far and the wide, at the fall and the waves’ rise a crescent moon of dorsal fin…

An archipelago of long forms…

Floating islands turning, wide...

The flash of pallid sun in the damp of Arctic Circle light…

Like magic!

They come:

Bottlenose whales in alongside.

One of the whale’s flukes breaches above the water. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Some pass under the keel. And finding none like us, return.

They raise themselves as much as they can to make their deep eyes shallow; to see as much as they can. As long as they can. As we drift. Engines cut. A listing hulk. And they follow looking up and up.

Their desire they cannot escape is my desire I cannot escape, to look, into the eyes, of the Other! This is how we speak, each to the Other. I do not want to leave here.

If I could I would abandon ship, stand on the rail and plunge…

If only my blood would not freeze...

If only I could hold my breath and dive, like them...

If only to quench my thirst I could drink brine....

We came from the sea and are still of it, our beating hearts the rocking of the tide, brought inside, so we could walk away. Having walked, there is no turning back.

An iceberg in the Davis Strait, just outside the Hudson Strait. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Flank speed into the starless dark we rove, the helmsman clinging to the wheel, the wavecrests snapping at our heels. Ice scrapes its nails along the hull, its prying fingers at the watertight doors.

And I am different than I was, Before.

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Thanks to Adventure Canada

- Mark Seth Lender's website

- Find the field note for this essay here

[MUSIC: Cal Scott and Kevin Burke, “Evening Prayer Blues” on Across the Black River, by Bill Monroe, Loftus Music

CURWOOD: Coming up – Thru-hiking twenty-six hundred miles on the Pacific Crest Trail.

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

MUSIC: The Charlie Haden Quartet, “Hello My Lovely” by Charlie Haden Quartet West, The Best of Quartet West, Universal Music Jazz France]

Journeys North: The Pacific Crest Trail

The Pacific Crest Trail runs 2,650 miles from the U.S. border with Mexico to the Canadian border. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth I’m Steve Curwood.

In a typical year, several hundred intrepid hikers walk all the way from Mexico to Canada, along the Pacific Crest Trail. At more than twenty-six hundred miles long, it covers some of the most challenging and spectacular terrain in North America. But it's not just about the pretty scenery. In his book Journeys North: The Pacific Crest Trail author Barney Scout Mann writes about the tight-knit community he and his wife Sandy found when they hiked the PCT. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb

The cover artwork of Journeys North by Obi Kaufmann depicts Thousand Island Lake and Banner Peak, notable sights on the PCT as it traverses the Sierra Nevada range. (Image: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

BASCOMB: So what drew you and your wife Sandy to hike the trail back in 2007?

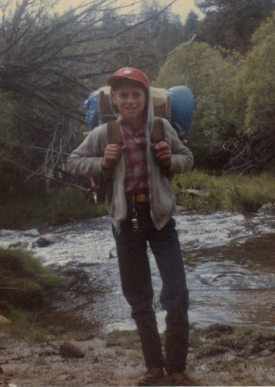

MANN: So you have to go a ways back. Both of us fell in love with backpacking at about the same age. I was 13 years old. And I was born into a household with parents who don't camp. But they took me at age 11, 12, 13 to Boy Scout meetings. And there at age 13, I went on a 50 mile backpack in the Sierra Nevada, John Muir's "Range of Light." I was, always been the smallest boy in any class at school, which is hard on a boy. It's no fun, I had to dance as fast as I could to make sure I wasn't the kid picked on, and it didn't always work. But out there, I saw stuff that I'd only seen on a TV screen, I grew up in Los Angeles. And so bears were not behind bars, I actually could see one. And hearing a beavertail slap in a stream, and seeing it. This was the real deal.

And the other thing was, out there, as long as I walked, and alright, I did have a 35-pound pack on a not-80-pound body, and that was hard, it was! But out there, as long as I kept up, I was the same as the big boys. So at age 13, I fell in love with backpacking. And for Sandy the same. My wife, Sandy, who has the trail name Frodo, and actually Scout is not my given name, but to thousands of people they only know us as Scout and her trail name, Frodo. She too, she'd see her brothers go off too on Boy Scout campouts, she'd think, I can hike! I want to do that. And it wasn't till later as a teen she got a chance.

Barney Scout Mann on his first 50-mile backpack in the Sierra Nevada in 1965, at the age of 13. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

And as she said, when we met a few years later, if I hadn't been a backpacker, she wouldn't have married me. In 2003, we'd already begun thinking seriously about doing a thru hike, as they call it, doing the entire Pacific Crest Trail. And we went out on the John Muir Trail, which is "only" -- and we use the word "only" very strangely in this community -- only 211 miles. We wanted to see if we'd come off that still being as enthused about doing a thru hike. And obviously we did, because in 2007, the summer of our 30th wedding anniversary, we set out to hike the Pacific Crest Trail.

BASCOMB: Mmm, wonderful. Well, let's get a lay of the land here. You start your trip from San Diego, you make your way down to the Mexico border, and then walk all the way up to Canada. How does the landscape change as the PCT makes its way from each border?

MANN: Well, there's both a micro and a macro answer. The macro is, it changes dramatically. You have some landscape that is out of Lawrence of Arabia, sand dunes, it's one day in the Mojave and you have some of it. And you have landscape that is, you are above treeline, it is barren, it is white granite that glitters in alpenglow. And you have everything in between. I saw one guidebook that identified 15 different plant and fauna zones, and the PCT goes through all of them.

Scout and Frodo at the Southern Terminus of the PCT, steps from the U.S.-Mexico border east of San Diego, California. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

But you might think, okay, I'll be walking and one day, I'll be in one thing, and then it'll slowly and gradually change. And it doesn't happen at all. The micro scale, literally in a half day's time, I can go through, easily, and many times, go through half of those different flora and fauna zones. I cross under a dirt underpass under Interstate 10, east from Los Angeles, at about 1800 feet, and I'm in what looks to you like desert. And within, okay, not a half day, but two-thirds of a day, I have climbed up into a pine forest and have gone through all the zones in between: the different desert zones; oaken. And the other thing, it's not just the landscape changing. Because we're out for five months, we're walking through seasons.

Every night on the trail, Scout would look up in the sky and spot the Big Dipper, follow it to the North Star, and just think for a moment: “That’s the way I’m heading. That’s what I’m doing.” (Photo: Patrick Beggan)

I see a plant, and actually, each of my three long hikes, I've done the Pacific Crest Trail, the Continental Divide Trail and the Appalachian Trail. Each one, there's a plant called skunk cabbage, or false hellebore. Each one of these trails, I would see it sprouting in the spring, just the little tiny tips coming up, almost like a bulb. It's only about a foot and a half tall, really thick, lush green, and it has little flowers. And I know I'm reaching the end of my hike, because at the first frost, a bit like a tomato plant, the plant just collapses. And it's like a starfish on the ground. And I know it's, my hike is beginning to end when I've seen that.

BASCOMB: Well let's talk a bit about the culture of these long hikes, starting with the idea of trail names. That's a nickname that's given to you by your fellow hikers. How did you get yours? And how did Sandy come to be known as Frodo?

MANN: So imagine if you got dropped down into a completely different place. If you woke up one morning and you were in Hogwarts, or you woke up and you were in Narnia, would you still want to be Bobby?

BASCOMB: Mmm, that sounds a little boring! [LAUGHS]

Frodo carefully crosses a stream in Oregon on a log bridge. (Photo: Barney Scout Mann)

MANN: This is actually a tradition that started on the Appalachian Trail. You do something stupid, maybe it's a play on your name. But trail names are usually given, sometimes thrust on you, rather than something you choose, although that happens on occasion. A guy who was named "Sky God" as his trail name, didn't take too long to realize that he had chosen that name for himself. [LAUGHS] The name Scout dates back to our 2003 John Muir Trail hike.

First day out, a young man attached himself to us like glue. Twelve miles later, we're climbing up Half Dome, and he was just out of high school, the two of us must have looked like parental types, and I hear this question behind me. And the question is, "What's the most important thing you've done in your life?" And at that point, I probably had three, four, five truthful answers to that. But the one that came out of my mouth was, "I was Scoutmaster of a large Boy Scout troop for five years." And "Scoutmaster" is a bit pretentious, and the book that we'd torn up -- and yes, we used to tear up books and put 150 pages at a time in our resupply up the trail so we wouldn't have to carry the whole book that time.

But the book we'd done that to, and that we were reading was To Kill a Mockingbird. And who would not want to be named after nine-year-old Scout Finch? Frodo -- I hope we have some LOTR, some Lord of the Rings fans out there. Frodo comes from, it's my fault. About a year before we hiked in 2007, I woke up and realized, oh my gosh, that's going to be the summer of our 30th wedding anniversary! She's not a jewelry person, but I really wanted to do something special. So literally, the idea sprang into my head, whole cloth. I could see a Pacific Crest Trail ring, a custom ring. And you could look at it from four or five feet away and you'd see the trail symbol, that "pregnant triangle", as we call it, with the tree in the center and the mountains backdrop.

The PCT ring that Scout gave to Sandy as they set out on the Pacific Crest Trail the year of their 30th wedding anniversary, earning her the trail name “Frodo”. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

And in the channel would be a small outline of the northern and southern monuments, and of the two primary mountains that you see on the trail, Mount Shasta and Mount Hood. I drove a jeweler crazy for about six months, but she actually did it! I give her the ring. We both cry. And if she was here, she'd say, Yeah, you cried more, which is true. I did! [LAUGHS] And the next day, we'd had a number of hikers who I had shown before I gave it to her, and all but as a group, they accosted her: "We want to see, show us the ring!" They said, "We know your trail name! You are the ring bearer. You're going on a long quest, a dangerous journey. You are Frodo!" And to this day, 13 years later, literally thousands of people, if not tens of thousands, know her simply as Frodo. And on her hand, she still wears the One Ring.

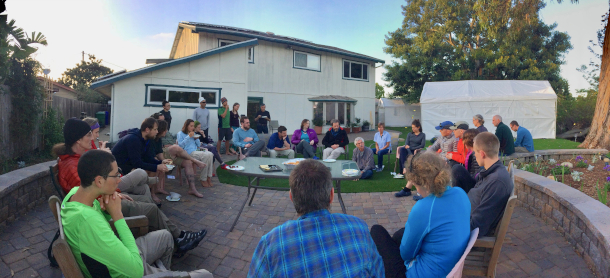

BASCOMB: Ah, lovely. And there are also people that are called trail angels. You and Frodo became known as trail angels for hosting people in your home. Can you tell us about that, please?

MANN: So you start with trail magic. And trail magic is literally any act of kindness toward a hiker, whether you pick up a hitchhiking hiker, whether you have a bit of your town lunch leftover, you've gone out on a day hike, and you run into a longer distance hiker, and you see them eyeing that piece of pizza you're just planning on taking home and throwing away, and you give it to them, and you've just made their day. That's trail magic. And you, who have done that, is a trail angel.

Scout and Frodo host an after-dinner talk with thru hikers, a few of the many thousands of hikers they have hosted over the years, about making the most of their PCT experience. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

And it goes from small to large. What we do is probably a bit large and maybe even obsessive. [LAUGHS] For about two months, we host hikers in our home. People from all over, about a third are internationals, and we'll have 30 to 40 hikers here a night, and we have this corps of volunteers, because it's all free. We had so much kindness in 2007 that came our way. You know, when we're out there in the small towns, we don't have the things we usually have at our disposal, and so many times and places along the way, we had trail magic, from trail angels. To be able to give back is, is great.

BASCOMB: That seems like something that's so rare in your day to day life, both A, relying on the kindness of strangers and having that appreciation for your fellow people and feeling like you want to give back to them, people that have been so generous with you.

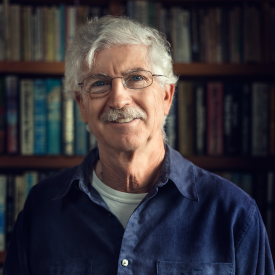

Barney Scout Mann is also a trail advocate who is currently serving as President of the Partnership for the National Trails System. (Photo: Patrick Beggan)

MANN: That's one of the things I love about the outdoors. It's one of the reasons I wrote the book too, so people who, their comfort zone is their couch, they can have a moment to experience what it's really like to be out there. And one of the neat things, as my wife likes to say, she thought the hike was gonna be so much about the landscape and stunning views, the pain and deprivation and trying, you know, the physical challenge. But at the end of the day, what it was really about -- gosh, I'm going to tear up a little bit! -- it was about the people. If you and I were coming at each other on a trail, and whether we're out there overnight, a week or, you know, in my case, five months, I would look at you from afar, a couple hundred yards away and say, "oh, there's another person!" I would think, "this person would give me the shirt off their back." And I would anticipate you would have the same thought in your mind, that the default attitude is we're kind to each other out there. I tell people that out there, on the trail, I found the community of people I've always wanted to be with, and I never knew existed.

BASCOMB: Is that what keeps you coming back to these long trail hikes that you do?

MANN: Why do I come back to it? A lot of reasons, a lot of reasons. One of which, of course, is that rich, rich sense of camaraderie. The other is -- well, the best way to explain it is, our hike of the Pacific Crest Trail is 13 years ago. And today, as I'm talking, I'm 69 years old. I was out there for 155 days. And Bobby, today, right now, I could sit here and tell you a story for each and every one of those 155 days. We are open out there in an entirely different way. We imprint differently. And around any bend, at any moment, a small miracle can happen.

BASCOMB: So you have this great story in your book about a big bear that you encountered on the trail one day. Can you tell us that story, please?

MANN: [LAUGHS] Yeah, I love it! Although it doesn't necessarily put me in the best light!

BASCOMB: Well . . . [LAUGHS]

MANN: So we are a thousand miles up the trail. We are actually just west of Lake Tahoe. And people we've leapfrogged with, that's, you'll see for a couple days, and you won't see for a week, or you might have a break with, and then see them the next day. They've all seen a bear! Not only that, they have their pictures, and they have their bear stories. And we have not seen a bear yet. What's wrong with us? And it's not that we haven't on many other earlier trips. But we don't have our Pacific Crest Trail bear story yet. And we've gone through the country where it's most likely, in the Sierra Nevada. So my wife and I are camping alone, which we did just over the majority of the time. And we were cowboy camping, which means not a tent, it was nice enough, and we enjoy that, to camp under the stars. We would trade off every night, one of us would do dinner and the other of us would set up our little campsite. So that's what I'm doing. I'm laying out our sleeping bags, my wife is about 20 feet away. And on the other side of her, about 50 feet away, I see pull around this large rock, the largest black bear I have seen in the wild.

Beautiful specimen, height of summer, sleek coat -- actually cinnamon colored, as black bears can be. And as I like to say, this thing was the size of a small Volkswagen. And I can tell, as I see him, I can tell by his aspect, where he's looking, he is not aware of us yet. The wind direction is such, and he's looking away. So what's my first move? Hmm. There's me, between me and the bear is my wife, right? My first move is a quick, hand down, camera up, and I get off two shots. [LAUGHS]

A black bear “the size of a small Volkswagen” approaches as Frodo cooks dinner. (Photo: Barney Scout Mann)

But all the way I'm watching him! And then I get her attention, I go, "fftt!", just make a little noise. She looks at me and I flick my head and she looks, sees the bear. And she takes the pot of food, puts it in our bear canister, cranks down the lid, comes over, stands by me. And she says "what do we do?" She knows: what you want to do is look large, and show them you're human. And I guess a lot of people think banging on pots means that we're human because that's what people can do, or clicking your hiking poles together. But what we did was we sang, in two-part harmony, Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah" to the bear. And as we reach the chorus, he turns his massive head and looks at us, long enough for us to know and acknowledge whose house we are truly in. And then he turns and slowly ambles away.

Scout and Frodo, a.k.a. Barney and Sandy, backpacking in 1977, the summer they were married. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

BASCOMB: So after walking some 2600 miles, you're just a few dozen miles from the border with Canada, from completing this entire hike that you've been doing, when a series of powerful snow storms dump just several feet of snow on the Cascade Range in Washington where you were hiking. What was it like to face that final test when you were so close from finishing?

MANN: Oh! We thought we had this in the bag. And at that point, this is now late September. At that point, you feel like you're in a vise. The days are growing shorter, so I have less time to walk. I see it all around me. I see it in the colors. I see the huckleberries are now gone and they're bright red. I feel it in the weather. And I feel it miserably at times in the weather. And you feel it in your body. I've been charging for now close to five months, and I'm getting messages from lots of different parts! And it's not just me, it's the young ones, too. We're being, we feel it. It's time to shut down. And we know, you can also feel, we have Canada in the bag! It's almost every year safe to finish by October 15th, I've seen people even finish October 31st. Because the snows at some point, shut down the trail. September 29, we are 60 miles from the Canadian border. We need three days and two nights. Unbeknownst to us, as you just said, a series of storms have lined up out of the Gulf of Alaska. And that night the first one hits.

I remember waking up and seeing the first snowfall: "Oh, this is sort of, you know, this is sort of cool!" And then as it starts to weigh down on the tent and you have to knock it off. And then it's, we're waking up to three, four inches already in the ground. And what's this going to be like? How much more is it going to go? And that day, we fairly quickly have a high pass. We're climbing first thing two thousand feet. We have a young woman, Blazer, one of the main other folks in the book Journeys North, we were close enough that she would call us her trail parents, her trail mom and trail dad, we'd call her our trail daughter. And Blazer, her, her jacket zipper's broken and she's lost a glove. I have, I have taught snowshoe backpacking. I'm experienced in snow backpacking. And as we get toward the crest of Cutthroat Pass -- what a name, huh! -- snow's been getting worse and worse, it's now over our ankles, and trail finding is an issue. This is days before anyone routinely carried a GPS or you had one on your phone. We have paper maps. And we see four people we know: Guts, Chuck Wagon, Dalton and Chigger. Do you love those trail names?

Frodo hikes in thick snow just 50 miles from the northern end of the PCT. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

BASCOMB: [LAUGHS] I do! Chuck Wagon, that's great.

MANN: Three guys and a gal, Chigger was a gal. They're heading toward us! Why are they heading toward us, this is wrong! And they say, "We have just turned around. The trail has become impossible to find. We're heading back to a road head. It's the last paved road, five miles back down at the base, and we're gonna hitch into the little tiny town Winthrop and see what the story is." We stand there in snow that's almost whiteout, and it's getting deeper by the moment. And for 10 minutes, I talk. Weighing it over; and, reluctantly I said, "Okay, maybe that is the best thing." And I turn and I take one step, South. I who have been heading north for five months. And I stop in my tracks. I can't go South. And I open my mouth. And I start to talk again. In the meantime, Blazer said I'm doing whatever Scout and Frodo are doing, and we felt likely the group would do the same. My wife and I had a tacit agreement. She did something that, as I'm talking there in the snow, it's the only time that she's ever done in our marriage. We've now been married 43 years. After about two minutes of me jawing again, she says "Scout, I'm exercising my veto. We're going back." I stop, stop talking. And we started heading down. And that was the first time [LAUGHS] we retreated from the snow!

BASCOMB: But you did finish eventually. You made it to Canada.

MANN: Yes, I'm still here. And we did make it to Canada that year, yeah.

BASCOMB: [LAUGHS] Yeah, I imagine; you make it sound like, you know, the geese that are flying South for the winter. They can't turn around and go North. That's just against what's ingrained in you at that point.

MANN: Yeah, yeah, there was this intense drive. Every night I'd go out and I'd brush my teeth. And on the Pacific Crest Trail, most nights were clear. And I'd look up in the sky and I'd spot the Big Dipper. And then I'd go from those two sides of the pot and I'd go six lengths out and I'd eyeball the North Star. And I'd just think for a moment. That's the way I'm heading. That's what I'm doing.

Despite three blockbuster snowstorms in the last miles of their hike, Scout and Frodo (pictured at far right), “trail daughter” Blazer, and the rest of their trail family did, eventually, make it to the border with Canada. (Photo: Courtesy of Barney Scout Mann)

CURWOOD: Scout Mann’s book is Journey’s North: The Pacific Crest Trail. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb

Related links:

- About Scout and Journeys North

- Learn more about the PCT

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Lovers Paradise” on The Dark Before the Dawn, Atlantic Jazz]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Anna Canny, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Joshua Siracusa, and Tivara Tanudiaia and Jolanda Omari.

Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio.

I’m Steve Curwood

Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth