This Week's Show

Air Date: June 7, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Alaska's Rusting Rivers

View the page for this story

Streams in northern Alaska are turning a cloudy orange, and scientists think the cause is metals like iron leaching from melting permafrost as the Arctic rapidly warms. Jon O’Donnell is an ecologist for the Arctic Inventory and Monitoring Network at the National Park Service and discusses the research and potential consequences of these changes with Host Jenni Doering. (11:38)

'No Place to Hide' In Pakistan

View the page for this story

Summer has barely begun in the Northern Hemisphere but extreme heat is already baking Pakistan, where climate disruption is also bringing frequent catastrophic floods. Rafay Alam, an environmental lawyer and member of Pakistan’s Climate Change Council, joins Host Steve Curwood to describe what it’s like to be in Lahore right now, how people are trying to cope and why these climate disasters are compounding Pakistan’s economic and security challenges. (19:00)

Mexico's 'Presidenta' and Climate

View the page for this story

Claudia Sheinbaum, the first woman to be elected President of Mexico, has a background in climate and energy, having co-authored two IPCC climate reports and later implemented clean transportation projects while mayor of Mexico City. Sheinbaum has pledged to boost renewable energy in Mexico but her political links with the current oil-friendly administration could present challenges to reaching green goals. Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran joins Host Jenni Doering to unpack Sheinbaum’s record and hear how Mexican scientists are responding to her election. (08:04)

BIRDNOTE®: Resplendent Quetzal

View the page for this story

Birds tend not to pay attention to borders between nations, and many routinely migrate between the United States and Mexico each spring and fall without showing any papers whatsoever. But if you happen to live north of that border, you’ll need your passport to go see one incredibly remarkable bird called the Resplendent Quetzal. BirdNote®’s Lucina Melesio has more. (02:11)

From the History Books

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Host Steve Curwood and Living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra mark 100 years since the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act. Though a step towards equality Native Americans had to wait until 1957 to secure nationwide voting rights. Also, it’s 60 years since the commissioning of the pioneering submersible ALVIN, which went on to discover the unique ecosystems around hot deep-sea vents. (03:07)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240607 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Jon O’Donnell, Rafay Alam

REPORTERS: Paloma Beltran, Peter Dykstra, Lucina Melesio

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. A voice from inside the heat waves in Pakistan on the climate emergency.

ALAM: Climate change is everything change. This is it. This is the coolest summer of the rest of our lives. We have put so many greenhouse gases into the atmosphere as a society that's chosen these decisions to block in 1.5-, 2-degree global warming by the middle of this century, if not quicker.

CURWOOD: Also, Alaska’s melting permafrost is turning rivers orange and threatening wildlife.

O’DONNELL: The stream where we were monitoring, when we first went there and when it was a clear water stream, it had a really healthy fish population. When we went back after the stream changed color and it had turned orange, there were no fish. All the fish were gone.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth - Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Alaska's Rusting Rivers

Some streams and rivers in Alaska’s remote Brooks Mountain Range are turning orange. Researchers think melting permafrost may be the culprit. (Photo: Josh Koch, U.S. Geological Survey)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. The rapid climate change happening to our planet is often invisible. Think of rising carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, or heat waves across the globe. But in the far north of Alaska, some changes are impossible not to see. That’s because dozens of crystal-clear streams in the Brooks Range are turning a cloudy orange. A 2024 paper published in the Nature journal Communications: Earth and Environment connects the change to rapidly thawing permafrost that appears to be releasing metals like iron into these streams. Lead author Jon O’Donnell is an ecologist for the Arctic Inventory and Monitoring Network at the National Park Service, and he joins us now from Anchorage. Jon, welcome to Living on Earth!

O'DONNELL: Thanks for having me.

DOERING: So when did you first notice that the streams in Alaska's Brooks Range looked rusty? And what was your reaction?

The Akillik River in 2017 (left) versus in 2018 (right), Kobuk Valley National Park, Alaska. (Photo: Jon O’Donnell/NPS)

O'DONNELL: So we were monitoring a site in Kobuk Valley National Park, on the Akillik River. And we had been collecting samples there, water samples and biological samples, like fish and bugs. That was in 2017. And when we went back in August of 2018, for a site visit, we noticed that the stream had turned orange. And this was surprising to us. And so, you know, we were accessing this site in a small helicopter. And you know, my initial thoughts were, this is kind of an important thing to document. But I kind of thought it was maybe just anomalous, or a case study, where, you know, this might just be a one-off thing, but it'd be a good story. So we should do a good job, collect all the samples that we need to collect. So we grabbed water samples, and we collected fish and bugs. And then when we went back out in 2019, we were flying around the region, and we noticed that there were more streams than we had previously noticed, had turned orange. And that was kind of when I started to think that this might be a bigger issue than this anomalous one stream in Kobuk valley, that it may be a bigger issue. And at that point, we started trying to compile observations from across the Brooks Range.

DOERING: So you mentioned that you did some water sampling. And you were finding these minerals in the water samples. What kinds of minerals have you been collecting?

The researchers found elevated concentrations of iron, arsenic, zinc, copper, and cadmium in the orange streams. (Photo: Josh Koch, U.S. Geological Survey)

O'DONNELL: Yeah, so we collect water samples from these orange streams, and then nearby clear-water streams. And we measure the same suite of chemicals on all of them. So the orange in the stream, that is a reflection of iron. And so those are iron particulates, it makes the stream very turbid, or filled with particles. And then those particles often get deposited on the stream bed, and so they blanket the rocks and the sediments in the bottom of the stream. But in addition to the iron, we see that these orange streams are more acidic, so they have a lower pH than, than clear-water streams. And there's a whole range of trace metals that are potentially toxic, both in terms of drinking water and for life that are living in these streams. And so examples of those trace metals that we've seen are like zinc and copper, and arsenic and cadmium and a range of others that are elevated in concentration in the orange streams.

DOERING: So what do you think is going on here? What do we know about what might be causing this change in these streams and rivers?

Mike Carey, Research Fish Biologist for the U.S. Geological Survey, collecting stream macroinvertebrates (bugs) on the Kugururok River, Noatak National Preserve. The researchers found a decline in bug and fish populations in the orange streams they studied. (Photo: Jon O'Donnell/NPS)

O'DONNELL: All of our observations point towards climate and permafrost thaw as a driver of this change. The reasons for that are one, the timing. So we've documented over 70 streams and rivers that have changed in the very recent past here, so in the last 10, 10 to 15 years. And this is a period of time where the climate has warmed dramatically in the Arctic. There's also evidence that in these specific watersheds, the climate has warmed past the point where permafrost can stay cold and stay frozen. And so we know that permafrost is thawing in this region. And when permafrost thaws, that changes the hydrology of these watersheds. So you can imagine these mineral deposits being contained in what is essentially a freezer. And as the permafrost thaws, that's kind of like shifting them to a refrigerator. And so now things can melt, ice can melt, water can flow. And so what we're seeing is that we think groundwater is flowing through these soils and mineral deposits, where permafrost has thawed. And that is creating this chemical reaction that's releasing all these metals and acid into the streams.

DOERING: Why are these metals and chemicals concerning? What effects could they have on wildlife and people in the area?

The researchers hypothesize that melting permafrost allows groundwater to flow through mineral deposits, causing chemical weathering. (Photo: Josh Koch, U.S. Geological Survey)

O'DONNELL: Right now we're working to try to determine if these concentrations of metals have exceeded EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, thresholds for both aquatic life and for drinking water. And so we don't have a definitive answer on that yet. At the concentrations, we know that this would affect taste of drinking water, so it might be more metallic. But one of our concerns is that these metals will be accumulated from the base of the food web, through like algae and macroinvertebrates or bugs that live in the bed of the stream, up into fish, you know, similar to what people have shown with like mercury that can bioaccumulate and magnify within a food web, and then it gets into fish and then into people if they eat the fish. So we're concerned because these metals could be toxic both to aquatic life, but into the people that might rely on the fish as part of their diet. And the stream where we were monitoring, and it changed from clear water to orange, when we first went there, and when it was a clear-water stream, it had a really healthy fish population. So lots of small Dolly Varden. And these little resident fish, called slimy sculpin, there was just a lot of them. When we went back after the stream changed color, and it had turned orange, there were no fish. All the fish were gone. We did the exact same protocol for sampling, and the fish had disappeared. And the macroinvertebrate insects, the bugs that reside in the bed of the stream, their numbers declined dramatically with this change. So our thought probably is that the fish migrated out of this river to a better habitat. But there's also a chance that they were impacted by this bioaccumulation of metals up through the food web. And so this was just one instance, where we've measured this, we're continuing our work now to try to figure out really, how are these fish being affected, but our initial thought is that the fish just left, the stream turned orange, and it was not a good habitat for them anymore.

Most areas in Alaska’s Brooks Range are only accessible by boat, small airplane, or helicopter. The team of researchers take a break next to R44 helicopter in Kobuk Valley National Park in 2017. (Photo: Mike Records/USGS)

DOERING: It's amazing how rapidly these changes seem to have happened. I mean, it's, you know, one year to the next, you notice these really rapid, significant changes, which is rare often when we're studying what's happening with climate change. How extensive is this issue in Alaska and beyond?

O'DONNELL: These observations that we have sort of span from the lower Noatak River Basin, in the West, all the way to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in the East. So it's, you know, over 1,000 kilometers. We've also been getting reports of observations from other areas in Alaska. So the North Slope, north of the Brooks Range, the Yukon River Basin to the south. So these are all watersheds and regions that are in permafrost zones. And so it's possible that permafrost thaw is driving these observations elsewhere. There is some evidence in the literature for this kind of thing to be happening in non-permafrost regions, such as in the Alps, and in the Andes, in South America, where you have mountain glaciers, and when these glaciers melt, you expose minerals and rocks. And so similar process, except in these other regions, we're talking about glaciers melting, as opposed to permafrost thawing.

Brett Poulin, Assistant Professor of Environmental Toxicology at UC Davis, and Taylor Evinger, graduate student at the Poulin Lab, UC Davis, process water samples from an upland orange stream in Noatak National Preserve (Photo: Jon O'Donnell/NPS)

DOERING: You know, this era that we're living in is often called the Anthropocene, the age that's shaped by humans. And it sounds like in this case, we're changing geological processes. I mean, climate change is changing so many different geological processes, but it's even changing the way that minerals are coming out of the soil.

Brett Poulin collecting a water sample from a small stream in Noatak National Preserve. (Photo: Jon O'Donnell/NPS)

O'DONNELL: Yeah, and I would say that the Arctic, because it's so remote, and because of some of the unique features of the Arctic, it's changing at a faster pace than other regions, like temperate and tropical regions and the globe as a whole. You know, I think the latest evidence shows that the Arctic is warming about four times faster than the Earth as a whole. And because of that, and because of the permafrost, and because of how much carbon and other things are stored in the soils up here, there's potential for really rapid change, and really dramatic alteration of ecosystems up here that you don't necessarily see in other parts of the planet. And so yes, the fact that there are these anthropogenic warming effects that are driving climate change in the Arctic, and permafrost thaw, and ultimately, this release of mineral compounds, trace metals into streams, that's a really unique set of factors that we wouldn't necessarily have foreseen when thinking about climate change in the Arctic.

DOERING: Jon, what is it like to be studying this and seeing these changes as a scientist?

Josh Koch, Research Hydrologist for the US Geological Survey, off to measure discharge (flow rate) at an orange stream. (Photo: Mike Carey/USGS)

O'DONNELL: Yeah, so I've been working in Alaska now for over 20 years. And I view my job as an ecologist, is basically to document the changes that are occurring. And I've worked on a number of different types of studies related to wildfire, permafrost thaw, and carbon cycling, things like that in the Arctic. This is by far the most surprising set of observations that I've been a part of in my time up here. And I think that it is shocking in terms of how fast it's happening and the spatial scale at which it's happening. As somebody who has documented these changes for over 20 years, I've become somewhat used to or maybe desensitized from some of the more dramatic things going on. When I sent this paper to my parents who live on the East Coast in Philadelphia, they responded by saying that they were depressed and saddened by what they were seeing. And because I'm so used to just functioning as a scientist, I maybe separate my emotional responses from some of these dramatic things that are happening up here. But talking to the public and talking to my family and friends, I've kind of been forced to realize that there's this emotional response that people have to wilderness and to nature, and to places like national parks that people love to go and visit, and when they see them undergoing this sort of change, it's upsetting.

DOERING: Jon O'Donnell is an ecologist for the Arctic Inventory and Monitoring Network at the National Park Service. Thank you so much, Jon.

O'DONNELL: Thanks so much for having me.

Dr. Jon O’Donnell is an ecologist for the NPS’ Arctic Inventory and Monitoring Network and the lead author of the paper. (Photo: Mike Records/USGS)

Related links:

- Nature: Communications: Earth & Environment | “Metal Mobilization from Thawing Permafrost to Aquatic Ecosystems is Driving Rusting of Arctic Streams”

- Watch a video about Alaska’s rusting rivers from UC Davis

[MUSIC: R. Carlos Nakai & Will Clipman, “First Morning” (Putumayo Version), on Native America, by Will Clipman, Putumayo World Music]

CURWOOD: Just after the break, an overheated Pakistan is struggling in the climate crisis. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Kenny Burrell, “Chitlins Con Carne” on Midnight Blue (The Rudy Van Gelder Edition), Blue Note Records.]

'No Place to Hide' In Pakistan

Jhelum River in the Pakistani province Punjab, on June 25, 2023. Summer heatwaves have recently hit temperatures of over 120 °F in the area. (Photo: Shanzay Asif)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. 2023 was the hottest summer on record in the Northern Hemisphere, and 2024 seems likely to top it, with torrid temperatures already sizzling the Southwest U.S., North Africa, South Asia and much of the Middle East. The climate emergency is not only battering whole regions with heat. Extreme storms and rain events are adding misery in places like Pakistan, which has yet to recover from catastrophic floods in 2022. And right now, Pakistan is in the grip of yet another extreme heat wave, with schools in the Punjab forced to close as some cities reached more than 120 degrees Fahrenheit. For a view from Lahore we are joined now by Rafay Alam, an environmental lawyer and member of Pakistan’s Climate Change Council. Welcome to Living on Earth!

ALAM: Thank you very much, Steve.

CURWOOD: With June just having arrived, summer has got a long way to go across Pakistan. How would you say summer has been different this year, compared to the last few years?

ALAM: Well, it is extremely hot in Pakistan. It's what's now called the Asian heat wave, or the South Asian heat wave of 2024. And we've seen temperatures since the middle of May through now, the first week of June, in excess of 50 degrees centigrade, which is, you know, it's well over 120 degrees. Lahore today, where I live, is 44 degrees centigrade, which is about 111 degrees Fahrenheit. The interesting thing is, while we are experiencing a heat wave right now, and I want to get into detail with that, April was the wettest April in all of Pakistan's recorded history. There were torrential rains in the northern and western parts of Pakistan that actually led to over 120 deaths. So what we are experiencing is not just a heat wave, but actively the climate crisis. And so, you know, I'm very clear that this is the coolest summer of the rest of our lives. It's only going to get hotter and hotter from here.

Wheat fields nearing harvest season. Due to the extremity of heat waves in recent years, Pakistan’s agriculture sector is being affected disproportionately. (Photo: Shanzay Asif)

CURWOOD: Yeah. Remind us of what happened with the torrential floods that you had in the recent past in Pakistan.

ALAM: Well, in 2022, we had historic floods, and we're talking 400 to 800% of monthly averages falling within a couple of weeks. And that, too, in areas outside the Indus Basin, which is Pakistan's major river network, so essentially, in places that couldn't drain the water away into the basin. And it was rainfall that saw not just flooding in our rivers, but also this 100-kilometer lake that was created by this rainfall, affecting over 30 million Pakistanis, displacing over 10 million Pakistanis, and causing in excess of $35 billion worth of infrastructure damage. That was just two years ago. And that was, again, in 2022 we had an early summer, summer started in March. We had a heat wave then. And then by July we had biblical floods, as it were. Last year, we had rains through April, which is unusual. And again, a warm summer. But this summer is breaking all records. We've had, incidentally, just a few days ago, a city in Pakistan, Mohenjo-daro, actually the home of an ancient civilization, that recorded 53 degrees centigrade, so in excess of 125 degrees Fahrenheit, and it was the hottest place on Earth last week.

CURWOOD: So, by the way, how has Pakistan recovered from those floods of 2022, never mind what's going on today?

ALAM: It's difficult to say, because a lot of the flooding took place, as I said, outside the Indus Basin, so outside where it could be drained, in really far-flung areas, not very heavily inhabited, but obviously very devastating for the people who live there. I mean, roads were swept away, schools were swept away, hospitals were swept away. And this sort of infrastructure takes years to rebuild. So we're facing a generation of Pakistanis who will grow up without access to hospitals, until the roads are built and until the hospitals are built, or even schools and the ability to get to work. So it is absolutely devastating. It crippled the Pakistani economy. I mean, $30, $35 billion of infrastructure loss is approximately 10% of our GDP, and we are in an IMF program at the same time. So our ability to economically stand on our feet has been made worse, much, much worse, especially by the fact that since the floods, a lot of the flood relief that we expected has come in the form of loans, and not things like grants and aid, which has doubled Pakistan's external debt in the last two years as well. So economically, very, very harsh. It's affected people, it's affected livelihoods, it's affected livestock. Truly devastating.

CURWOOD: It sounds just horrible. So let's talk about today, now. You're in Lahore, Pakistan. What are people doing there where you are to cope with this insane heat wave?

ALAM: Well, we have advisories. We have something called the National Disaster Management Authority, which has a heat wave plan for all of Pakistan, which generally involves letting people know that it's dangerous to go out, to consume lots of water. Also in Punjab, which is the province that I live in, first of all, school timings were changed so that schools wouldn't be let off in the mid afternoon. They were being let off by 12, one o'clock. And then as temperatures rose, schools were shut down throughout Punjab. We've had hundreds of people affected with heat waves. And I should also point out, in 2014, the Pakistan's largest city, Karachi, faced a week-long heat wave where over 1,000 people died. And we're reaching those sorts of temperatures right now, which puts human lives at serious risk. So we're seeing all of these things play out, and I might also—I mean, I go for a walk in the evenings when the sun sets. It's not unpleasant, but I noticed driving around and walking, animals, birds, collapsed to the ground looking for water. Dogs on the side of the road unable to get up. And I recall that this heat wave affects the wildlife in Lahore as well, the birds, the cats, the dogs, the other animals as well, who are hugely put out by just the amount of cement we have in our cities. As you know, cities are usually warmer than other parts, you know, where there's natural vegetation, something called the urban heat island effect. So while it might be 50 degrees centigrade outside, it might feel several centigrades higher than that. And it's impacting everyone.

Amid scorching heat waves, the city of Lahore awaits the respite offered by the monsoon season. Pictured above, a view of the Minar-e-Pakistan after a monsoon cleanse in late July. (Photo: Shanzay Asif)

CURWOOD: So as a member of Pakistan's Climate Change Council, what's to be done? What you folks in government doing to help people cope with this situation?

ALAM: Well, I mean, I'm a member of the Council, but the less said about it, the better. It's only met four times in its last seven years. And mostly to agree on what Pakistan's position at the Conference of Parties is going to be at. We're a country of over 200 million people, a vast majority of whom are now exposed to dangerous amounts of right now dry heat, which is also dangerous. But as the monsoons, the rain precipitation comes in towards the end of June and July, we're going to see rising humidity levels and something called wet bulb temperatures, where even at lower temperatures, if the humidity is higher, so for instance, if you're at 95 Fahrenheit and 70% humidity, it will feel like it's over 120 degrees Fahrenheit. And especially with the higher humidity, it becomes very, very difficult for the human body to release heat on its own through sweating. So people essentially will bake in these sorts of temperatures. So we are extremely at risk of high temperatures, not just human beings. But then Pakistan's economy, we have about 20% of our GDP is from agriculture. And just a few days ago, one of the leading English newspapers had a headline about how crops were being decimated in Pakistan. Cotton crops basically sizzling. Maize crops, mango crops, other vegetables and fodder for animals as well. So there is going to be a decline in crop productivity, which of course equates to a decline in farmer livelihood. And although farming contributes about 20% to the GDP, nearly half the Pakistani workforce is associated with agriculture. So we're talking about these temperatures and the loss they're causing to crops really pushing Pakistan's workforce towards or under the poverty line as well. Now, not just human beings, not just crops, but crops being decimated by heat. But as a result of the heat, there is an increased demand for water and for energy, water for crops to prevent them from burning, and then energy as people turn fans and air conditioners on. And we've seen in the last couple of weeks, our old grid system collapse under the sort of accumulated weight of this spiking demand. So and that's its own problem, because with these sorts of temperatures, people actually need shelters, we need to have places where people can go and have access to electricity, to things like air conditioners, because, you know, wet bulb temperatures, it doesn't matter if you have a fan, the humidity won't allow you to, to sweat, you need to have access to air conditioners and electricity. So we're also suffering an energy loss or a loss in energy because surging demands. So all of these things have to be looked at.

CURWOOD: What are the risks here? How important are those risks?

ALAM: You know, central to my argument here is that the World [Weather] Attribution group, which looks at climate events throughout the world to see whether or not they can be attributed to global climate change and global warming, has already stated that the heat waves last year and this year are on account of the 1.2, 1.4 degrees centigrade global warming we've experienced. So these heat waves are not a natural occurrence. This is very much a manmade occurrence. People like myself, people in Pakistan, people in India—by the way, over 55 people have died in India because of heat waves. So this heat wave is a manmade event due to the greenhouse gases consumed and thrown into the atmosphere by the Global North since the industrial revolution. So at some level, these greenhouse gases have to stop. Otherwise places like Pakistan, which contributes less than 1% to global greenhouse gas emissions on a year-to-year basis, is paying the bill for other countries' industrial and economic expansion. You have to stop those greenhouse gases. Otherwise people throughout South Asia are going to be exposed to high and very dangerous levels of temperature, which is also going to produce these dustbowl conditions in our agriculture belts. We have to change the way we do agriculture; we'd have to have heat-resistant crops. We grow our own food right now, but there's no crop in existence that can withstand 50-plus-centigrade temperatures. We have to come up with better varieties of seeds that are more heat resistance. We have to come up with other forms of agriculture, large-scale agriculture that can take this rapid increase in temperature. We have to change our water economy. I've already mentioned that agriculture contributes about 20% to GDP, but over 90% of Pakistan's water goes to agriculture. We have to find a better ratio where this water can be used to provide resilience and sustainability to Pakistanis going forward. I mean, it's confounds me to think that 90% of Pakistan's water is used to produce 20% of its GDP, and employs 40% of its workforce close to or at the poverty line. And we need to change the way our cities are designed. The cities are designed for cars. They're not designed for human beings to withstand these temperatures. I'm not sure how to go about this redesign. But these are the big, bold things we need to do in the face of dramatic climate change.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about today. You say 40%, half to 40% of the workforce in Pakistan is in agriculture. And yet, you can't stay inside, you can't be by a fan or an air conditioner if you're working in agriculture. What's happening to the people who are working outside?

Deosai Plains, Skardu are at an average elevation of 4,114 meters (13,497 ft) above sea level and considered the second highest plateaus in the world. Pakistan’s natural wonders are widely under threat from climate change. (Photo: Shanzay Asif)

ALAM: Millions of people at risk of exposing themselves to dangerous levels of heat. But at the same time, this is harvest season. So they are people who are working. But luckily they wake up when the sun rises, they do a couple of hours work before it gets really, really hot, they’ll go back inside and they'll do a couple of hours work when it gets a little bit cooler in the evenings. But it is incredibly disruptive and dangerous at the same time.

CURWOOD: What you're describing, how's that different from an apocalypse?

ALAM: Oh, Steve, climate change is everything change. This is it. This is the coolest summer of the rest of our lives. We have put so many greenhouse gases into the atmosphere as a society that's chosen these decisions to block in a 1.5-, 2-degree global warming by the middle of this century, if not quicker. You see, Earth's ecosystem's been in balance since the last ice age, a balance that's allowed us to do enough agriculture to have human civilization, so that you and I can speak like this. That civilization is over. I mean, it's not like human beings are gonna become extinct. But this way that we interact with each other, extremely heavy energy use, extremely heavy water use, incredibly consumptive of natural resources, producing greenhouse gases for just about anything. I was reading something recently that the, the YouTube viral hit Despacito that reached 5 billion views on YouTube just a few years ago, expended enough energy on YouTube to power 40,000 U.S. homes for a single year. It's this behavior, this civilization, which is at risk. And yes, it is very much an apocalypse.

CURWOOD: There's a civil defense official who's asked people not to put cooking gas cylinders in open areas as a safety measure. And he's also warned the people living near fields that snakes and scorpions could enter homes and, and storage places in search of cooler spaces. What is he talking about?

ALAM: I think this is something that's heavily localized. A lot of domestic energy use in Pakistan is off of gas, and it's stuff that we use our ovens and our stovetops for. And with the weaker distribution system, a lot of rural areas rely on cylinder-based gas for their domestic purposes. And again, high temperatures, we're talking people in villages. So this is civil defense as part of the National Disaster Management Authority. And I'm glad to hear that some of their recommendations involve putting those canisters into cooler places and in shade. And then scorpions and snakes. Rural Punjab, rural Sindh, where there are scorpions, snakes, there are other animals as well. And like I said, they are being heavily impacted by this heat wave as well, and they're gonna look for shade. So be careful, especially if in the rural areas in Pakistan. You might meet some nasty creepy crawlies when you go into your hut.

A view of the serene mountains of Nathiagali, a popular summer destination for Pakistanis trying to escape the heat in their hometowns. (Photo: Shanzay Asif)

CURWOOD: Now, I imagine you've lived in Pakistan for much of your life. When did you wake up and say, Whoa, what's going on here?

ALAM: I was made aware of climate change 2008, 2009. That was also around about the time Al Gore's video An Inconvenient Truth came out. And every year, we see changes in precipitation. We see rainfalls when it shouldn't be raining. We—the wettest April that I was talking about just two months ago, it was again devastating for crops, because these were crops approaching harvest time, and if you're met with a heavy rain, a lot of the crops just fall down and rot. So there was already devastation because of that. We've seen these sorts of things. And people don't in Pakistan tend to think it's climate change but unlivable amounts of air pollution. And this is very much our own doing. This isn't greenhouse gases coming out of the Global North. This is some of the worst-quality fuels that we have. And as a result of which, fuels that we use in our energy sector and in automobiles, that on average, in Pakistani cities, you're losing two to three years of life expectancy. And in my city of Lahore, it's seven to eight years. So we've been seeing these chronic air pollution episodes since at least 2016. So this is happening all the time. We're seeing it every single day. There is a significant denialism on climate change in places like the United States. And it, it angers me, because I see people affected. I see animals affected. And this is a lived experience for the global majority, the Global South. And it's extremely infuriating to see people who've participated in this global warming deny it, deny any accountability, and try and move on as if nothing's happened, and try and continue to make money and drive that bottom line.

CURWOOD: You're an attorney, you're a lawyer, and perhaps not a political scientist. But what do you see are the political implications of this in terms of regional stability and worldwide stability?

ALAM: I am not a political economist or a political theoretician, but there's this fellow called [Anatol] Lieven in the United Kingdom who wrote a book on climate change and the nation state, and his thesis is that the nation state emerged in the 18th and 19th century from the kingdoms that ruled Europe. And it's predominantly a security state, you're involved in securing yourself against aggression from other states, but not from an existential threat like climate change. And so the very basis of the legal systems and the international system that we have, he argues, and I tend to agree with him, can't cope with an existential crisis like this. I mean, one of the worst ways to deal with something like climate change is to divide the world into 200 different countries and have them argue with each other. So this does not augur well for regional stability, not that there's a considerable amount of regional stability in Pakistan right now, or in and around Pakistan, because on one side, we've got Afghanistan. On the other side, we've got India, with which we've had an acrimonious relationship for most of our life. So we're not talking to either neighbor, which can't be good at the end of the day, because people are important. And there are also climate-induced migrations, a lot of them, of course, political as well, when it comes to Afghanistan, but climate-induced migrations that we have no consideration for, because there is still no legal definition of a climate migrant internationally. So there's that we don't have our eyes open for that. So it doesn't augur well for regional stability going forward, or even the international order.

Melting snow on the typically-snow-capped peaks of Naran Valley, draining into Saif-ul-Malook Lake. Excessive melting in 2022 led to intense flooding. (Photo: Shanzay Asif)

CURWOOD: What portions of Pakistan are less vulnerable to climate disruption, and where people might be migrating to?

ALAM: Well, vulnerability is interesting. I mean, of course, vulnerability is the strength of your infrastructure to withstand climate events, but also vulnerability at a higher level, your ability to get on your feet if you've been pushed to the ground. And this is dramatically different, not just on an infrastructure scale, but a scale of affluence, right? The richer you are, the more likely you are to be resilient to climate impact. And the less affluent you are, the more likely your home's going to get swept away. But my concern really comes to the majority of the Pakistani people, you know, who are middle class, working class, and at or close to the poverty line, that their ability to withstand climate shocks is much weaker than my own. So we have to understand vulnerability in that way. So where in Pakistan is vulnerable? Most of it, because most of it is poor, and you'll have some pockets of rich Pakistan that will be less vulnerable. If you think you can head to the mountains and enjoy some cool weather over there, well, we have over 3,000 glaciers in Pakistan which are at risk of something called glacial lake outburst floods, which are when the water of the glacier unexpectedly and unannounced makes its arrival and can be quite devastating. So 3,000 of those glaciers, some of which have split and burst and caused knocked-out roads, and especially up in the northern areas when we're talking roads and bridges that connect valleys and mountain ranges, if you knock out one of those you more or less knock out an entire region from other transport logistics, so you're not safe there very much either. Then if there's an excessive rainfall, the, the rivers that pass through the mountains can also disgorge themselves with flood. I'm sorry, Steve, there's really not many safe places unless you find a rich friend and stay in their house.

CURWOOD: No place to hide.

ALAM: No place to hide.

CURWOOD: Rafay Alam is a Pakistani environmental lawyer and member of Pakistan's Climate Change Council. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

ALAM: Thank you very much, Steve, for having me.

Related links:

- AP News | “Weather Forecasters Warn Pakistanis to Stay Indoors Ahead of New Heat Wave”

- Euro News | “Pakistan Heatwave: Hundreds Treated for Heatstroke as Temperatures Soar to Over 50C”

- Reuters | “In Pictures: Heatwave Scorches Pakistan”

- Learn more about Pakistan’s climate change response

[MUSIC: Malangaan The Band, “Malangaan Band - Instrumental mashup songs”]

DOERING: Coming up, Mexico’s first female president has a green background. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Gary Burton, “My Romance” on Next Generation, by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, Concord Records]

Mexico's 'Presidenta' and Climate

Claudia Sheinbaum made history as the first woman elected to become Mexico’s president. She has a background in engineering as well as climate science and contributed to multiple IPCC reports. (Photo: EneasMx, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. Mexico recently held presidential elections and in a historic first climate scientist Claudia Sheinbaum won with a decisive 60 percent of the vote. That makes her the first female president in all of North America! Here for more is Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran. Hi Paloma. So, who is Mexico’s next president?

BELTRAN: Hi Jenni. Yes, Claudia Sheinbaum is the handpicked successor of the popular president Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who founded the left-wing political party Morena. And during her victory speech on election night, thousands of ecstatic supporters gathered in Mexico City’s historic main square, the Zócalo.

ANNOUNCER: Claudia… Sheinbaum… Pardo!

CROWD, CHEERING AND CHANTING: Presidenta! Presidenta! Presidenta!...

BELTRAN: In her speech, the next “Presidenta” highlighted her plans to promote environmental protection.

SHEINBAUM [SPEAKING IN SPANISH]: Impulsaremos la restauración y protección del medio ambiente y los recursos naturales para garantizar la vida y el desarrollo de las presentes y futuras generaciones.

BELTRAN: She’s talking about the importance of safeguarding natural resources to guarantee life for present and future generations.

DOERING: You know, there’s been a lot of talk about her work on climate. So what’s the story?

BELTRAN: Yeah, so she has a PhD in energy engineering and completed her thesis at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab in California, focusing on energy use in Mexican transportation and buildings. She then joined the faculty at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, or UNAM, which is a prestigious public university in Mexico City. President-elect Sheinbaum served as both a contributing and lead author for the mitigation sections of the Fourth and Fifth Assessment reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, in 2007 and 2014.

DOERING: Oh yeah, and didn’t the authors of that 2007 IPCC report share the Nobel Peace Prize?

BELTRAN: They did, including Sheinbaum.

Claudia Sheinbaum served as mayor of Mexico City, a city of over 20 million people. (Photo: Kasper Kristensen, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: Wow. So Paloma, this is the first climate scientist that I’ve heard of winning a presidential election! And what is Claudia Sheinbaum's political background?

BELTRAN: So from 2000 to 2006, Sheinbaum served as Mexico City’s minister for the environment, while López Obrador served as mayor. Then in 2018, she was elected as mayor of this metropolis with some 22 million people. During her term she electrified Line 3 of the metrobus, a rapid transit line. She also developed rooftop solar projects and added around 30 kilometers of bike lanes throughout the city in efforts to encourage less use of vehicles. And Claudia Sheinbaum set the goal for Mexico City to become carbon neutral by 2050.

DOERING: Well, those sound like good steps, especially in a city that’s had notoriously unhealthy air quality.

BELTRAN: Right. But Xochitl Cruz, Professor in the Department of Atmospheric Science at UNAM, who participated in a recent environmental policy evaluation of the city, said that in the last five or so years, ozone levels have started to creep back up.

She also said the city’s government has fallen behind on financial investment to reach its climate mitigation goals.

Queremos que México sea una potencia de las energías renovables como lo hicimos en la Ciudad de México. Ayer se inauguró la planta solar de 18 MW en los techos de la Central de Abasto. ???????????? ☀️ pic.twitter.com/ccKOMl9nQy

— Dra. Claudia Sheinbaum (@Claudiashein) February 21, 2024

CRUZ: The budget allocated during her administration for environmental issues was declining over the years, being minimal from 2020 onwards. Forest fires increased, air quality deteriorated significantly. Access to water became more difficult, and conservation land was urbanized in an outrageous manner.

BELTRAN: As mayor, Claudia Sheinbaum oversaw the construction of a six-lane bridge that extends into the Xochimilco wetlands. And scientists and activists were very concerned that it would cause more damage to the wetland and to the last native habitat of the axolotl, a species of salamander endemic to Mexico.

DOERING: Oh! Those are such cute little guys, they always look like they’re smiling.

But anyway, people will be looking ahead to see how she runs the country as a whole. So what are the top environmental issues in Mexico?

BELTRAN: So Mexico is currently facing a list of environmental problems: There’s a water crisis in Mexico City, and a government agency said that last year, some 20 percent of the population didn’t have water during all days of the week. And there are droughts throughout Chihuahua, Guanajuato, Querétaro and more. Also, according to FEMA, the Atlantic and Caribbean Sea surface temperatures are getting warmer. And that will likely supercharge hurricanes across the Gulf and Caribbean coasts of México in the coming years. And scientists say this is all connected to climate change.

DOERING: Hmm. And Paloma, where does Mexico stand in terms of its presence in the United Nations climate negotiations?

BELTRAN: So I talked to Adrian Fernandez. He's worked for more than 30 years on Mexico’s environmental policy and attended almost 20 of the yearly UN climate meetings. He said that although the country used to be a climate leader among emerging economies, progress has stalled under the Morena party of López Obrador.

FERNANDEZ: Unfortunately, with the beginning of the current administration that is about to end, this administration totally neglected the environment and climate change, really, perhaps, thought that if they were to apply or or channel resources and efforts towards climate efforts, they had to forget about the social agenda. It's a pity, really, we wasted six years, the last six years were wasted regarding the environment and climate.

BELTRAN: Adrian and other scientists I talked with said that the government has prioritized state-owned oil and gas giant Pemex over private wind and solar power companies. He said two projects in particular raise environmental concerns: The Tren Maya, a railway that’s being constructed in the Yucatán Peninsula that will cross through forests and natural pools called cenotes. And what may turn out to be the third-largest refinery in Latin America, the “Nueva Refinería las Dos Bocas” in Tabasco that’s not yet up and running.

The ajolote or axolotl is an endemic species to Mexico city’s Xochimilco river and wetlands. Conservationists are concerned that the extension of Mexico city’s Periférico Bridge into the Xochimilco wetlands, a project carried out while Claudia Sheinbaum was mayor, will further endanger the precious salamander. (Photo: Dgzvs2012, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

FERNANDEZ: The refinery is not working. And very few countries, if any, is building new refineries at a time when we are moving in an energy transition to try to get rid of fossil fuels, not to build more refineries to produce more fossil fuels.

DOERING: OK, Paloma, well President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum is in the same Morena party as the outgoing administration, but during her campaign, did she promise a different approach in terms of the environment?

BELTRAN: So she has committed to investing more than [U.S.] $13 billion in new energy projects by 2030, focusing on wind and solar power generation and modernizing hydroelectric facilities. And she pledged to boost renewable energy to as much as 50% by the end of the decade. At the same time, though, she promised to finish what her predecessor started by completing the Tren Maya and the Nueva Refinería las Dos Bocas. So Jenni, Adrian Fernandez says the President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum has a choice to make.

FERNANDEZ: That’s a question for the country: If Claudia becomes Claudia, really independent from López Obrador, she can not only lead Mexico into become a major force in the world. She can become, almost right away, one of the greatest contemporary leaders in the world.

BELTRAN: And other Mexican scientists I talked to shared the same sentiment and hoped for more environmental ambition in the country. President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum will go into office October 1st.

DOERING: Thanks Paloma!

BELTRAN: My pleasure, Jenni.

DOERING: That’s Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | "Mexico Elected a Climate Scientist. But Will She Be a Climate President?"

- ClimateHomeNews | “Mexico Elects a Climate Scientist as President – but Will Politics Temper Her Green Ambition?”

- CarbonBrief | “Climate Scientist Claudia Sheinbaum to Become Mexico’s First Woman President”

- Reuters | “Can Mexico’s Sheinbaum, a Climate Scientist, Shake Lopez Obrador’s Oil Legacy?”

- Learn more about Adrian Fernandez Bermauntz

- Learn more about Professor Xochitl Cruz Nunez

- Track air pollution in Mexico City

- MexicoNewsLately | “Critics Say Mexico City’s Last Wetlands Threatened by Bridge Project”

- InsideClimateNews | “Protecting Mexico’s Iconic Salamander Means Saving one of the Country’s Most Important Wetlands”

- SmithsonianMagazine | “Mexico City’s Reservoirs Are at Risk of Running Out of Water”

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BIRDNOTE®: Resplendent Quetzal

A male Resplendent Quetzal perches atop a branch. (Photo: Norm Herr, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DOERING: Birds tend not to pay attention to borders between nations, and many routinely migrate between the United States and Mexico each spring and fall without showing any papers whatsoever. But if you happen to live north of that border, you’ll need your passport to go see one incredibly remarkable bird. BirdNote®’s Lucina Melesio has more.

BirdNote®

Resplendent Quetzal: Mexico’s Sacred Bird

Written by Lucina Melesio

[Guatemalan rainforest soundscape]

MELESIO: Deep in the forests of Southern Mexico and Central America, the Resplendent Quetzal is a sight to behold.

[Resplendent Quetzal songs]

And if you catch a glimpse of the bird’s emerald green feathers, fiery red breast and its striking blue tail that winds on and on, up to three times the length of its body, you might even think you’ve seen a flying serpent.

[Resplendent Quetzal calls]

Which is probably why the Aztecs considered this bird a representation of Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, one of the most worshiped gods across ancient Mesoamerica. Known as Kukulkan to the Mayans, the god was associated with creation and knowledge.

[Resplendent Quetzal songs]

But no matter how sacred, Resplendent Quetzals are currently considered near threatened due to a declining population. Deforestation and illegal trade are the main threats to their survival.

Quetzals hold an important role in their ecosystem. As they feast on fruits like avocados and wild aguacatillo, they scatter their seeds, playing a crucial part in forest regeneration.

A Resplendent Quetzal in flight. (Photo: Laura Wolf, Wikipedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

These majestic birds prefer cloud forests, building their nests in tree cavities. Both parents share the duties of incubating the eggs and raising their young.

[Resplendent Quetzal songs]

It takes two quetzal parents to raise a bird this magnificent.

I’m Lucina Melesio.

###

Senior Producer: John Kessler

Producer: Mark Bramhill

Managing Editor: Jazzi Johnson

Managing Producer: Conor Gearin

Content Director: Jonese Franklin

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. ML211598 recorded by Josue de León Lux, and Resplendent Quetzal ML6193 recorded by Anne LaBastille.

Resplendent Quetzal Xeno Canto XC326653 recorded by Beatrix Saadi-Varchmin.

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2023 BirdNote September 2023

Narrator: Lucina Melesio

ID# REQU-01-2023-09-19 REQU-01

https://www.birdnote.org/listen/shows/resplendent-quetzal-mexicos-sacred-bird

DOERING: For pictures, vuela or fly on over to the Living on Earth webpage, loe.org.

Related links:

- Bird Note | “Resplendent Quetzal: Mexico’s Sacred Bird”

- Learn More about Bird Notes

- Learn more about the Resplendent Quetzal

[MUSIC: Musica Mexicana, “Merengue Con Crema” on Pasion de Mexico: Traditional Meican Mariachi, Bolero & More, Megatrax Music]

CURWOOD: To get the stories behind the stories on Living on Earth, as well as special updates, please sign up for the Living on Earth newsletter. Every week you’ll find out about upcoming events and get a look at show highlights and exclusive content. Just navigate to the Living on Earth website, that’s loe.org, and click on the Newsletter link at the top of the page. That's loe.org.

[MUSIC: Musica Mexicana, “Merengue Con Crema” on Pasion de Mexico: Traditional Meican Mariachi, Bolero & More, Megatrax Music]

From the History Books

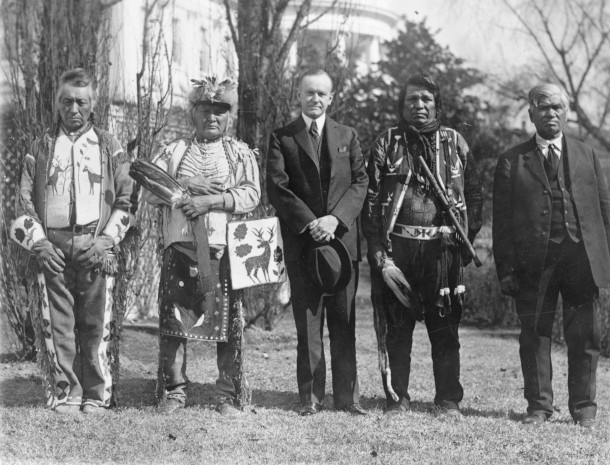

President Coolidge (center) standing with four members of the Osage Nation at a White House ceremony after signing the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924. (Photo: National Photo Company Collection, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia is Peter Dykstra, a contributor to Living on Earth and the master of the history books. Hey, Peter, what do you see for us today?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. June 2, 1924, 100 years ago, the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act. After 300 years of conquest and genocide, it hardly reflected a huge change in white America's attitudes toward Native America. But maybe a slight reversal of U.S. attitudes. Slight indeed, the law left the issues of voting rights for many Native Americans to individual states. American Indians did not have nationwide right to vote until 1957. And of course, poverty and all sorts of other ills have continued to plague Native American reservations and communities all over the United States.

CURWOOD: Indeed, and isn't it curious that one can have an American passport and say, an Irish or an Israeli passport for a number of years. And yet, it took until 1957 for the First Nation people to have the right to vote. But hey, as some say, the arc of the universe bends towards justice. Maybe too often too slow for, for many of us. Hey, Peter, what else do you see in the history books at this point?

DYKSTRA: June 5, 1964. Significant in a couple of different ways. My mom's birthday, of course, but also the 60th anniversary of the commissioning of the submersible vehicle Alvin by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. Its first significant mission didn't occur for two years, when Alvin dived to explore the possible site of a hydrogen bomb lost by a U.S. plane off the coast of Palomares, Spain. But Alvin became a mainstay of deep ocean exploration and discovery, and is celebrated as such ever since.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I mean, Alvin found those hot vents, those hydrothermal vents deep in the ocean, where there are living systems, deep sea ecosystems that exist without sunlight and are based on chemosynthesis. It's kind of amazing. And by the way, who was Alvin, anyway?

Swimmers recover ALVIN after a dive on the “Mountains in the Sea Expedition” in 2004. (Photo: NOAA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: Alvin is a mash-up of the name of oceanographer Allyn Vine. He was a big player back in the 1960s in oceanographic research in places like Woods Hole and Scripps on the West Coast. And Alvin memorialized his name forevermore.

CURWOOD: All right. Hey, thanks, Peter, for those stories. Peter Dykstra is a contributor to Living on Earth, and we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Steve, thanks a lot. We'll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth webpage. That's loe.org.

[MUSIC: Yoyo International Orchestra, “Yellow Submarine” The Love Songs of The Beatles – Instrumentals Volume 2, YOYO USA, Inc.]

CURWOOD: Next week on Living on Earth, Juneteenth is just around the corner, and we are looking at African American pioneers like Madam C. J. Walker. She developed a line of cosmetics and hair care products for Black women and became the first female self-made millionaire in America.

BUNDLES: Well, she was really very much a motivator. And while, you know, hair care is the, that's the—she made hair care products, she was really, in some sense, a motivator. So, she made these products. She knew that women needed these products for hygiene reasons, for hairstyling, versatility. But I think over a period of time, she began to see the hair care products as a means to an end. Part of it was, yes, we accomplished this, you know, we make hair care products, we make women have better hygiene, they feel better about themselves because they feel better about the way they look. But it also became a platform for women to become economically independent. One woman wrote to her, and she said, you have made it possible for a Black woman to make more money in a day selling your products than she could in a month working in somebody's kitchen. And then as she had her first convention in 1917, and she brought together 200 women who had been domestic workers, who had been farm workers, even a few schoolteachers, she saw that what they really needed was education and economic independence. And she told them at the convention in her keynote, “As Walker agents, I want you to understand that your first duty is to humanity. I want others to look at us and realize that we care not just about ourselves but about others.”

CURWOOD: Tune in to Living on Earth next time to hear about Black hair, joy and resilience as we get ready to celebrate Juneteenth.

Related links:

- Library of Congress | “Today in History – June 2”

- Learn more about the Alvin submersible

[MUSIC: Poncho Sanchez, “Afro-Cuban Fantasy” on Afro-Cuban Fantasy, Concord Records, Inc.]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Jake Rego engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org. I’m Jenni Doering

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth