August 9, 2024

Air Date: August 9, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Methane Tracking From Space

View the page for this story

A new satellite recently blasted off into Earth orbit with the important mission of tracking methane emissions from oil and gas infrastructure across the globe. Dr. Stephen Conley is an atmospheric scientist and joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain why free public access to the data from MethaneSAT is a game-changer for holding oil and gas companies accountable for climate pollution. (08:24)

Night

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

The vastness of space can provoke fear but the perspective it brings can also bring inspiration and even comfort. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender recounts the impact on his consciousness of a star-studded sky, planets in full view, and shooting stars. (03:18)

A Mars Testing Ground

View the page for this story

Since 2001 the Mars Society has run around 300 simulated missions at a remote site in the high desert of Utah, to study the effect of extra-vehicular activity or EVA on the human body and mimic field research people might run on Mars one day, such as looking for fossilized life. Mars Society President Dr. Robert Zubrin joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to describe the research station, what a day in the life of a participant looks like and says why he believes we should send humans to Mars. (14:54)

Life on Europa?

View the page for this story

Jupiter’s moon Europa is one of the most promising places to look for extraterrestrial life. Europa has a large liquid ocean beneath its icy crust, so NASA plans to launch the Clipper space probe later this year to investigate. As part of the mission NASA is sending a poem to space. US Poet Laureate Ada Limón reads aloud her poem, “In Praise of Mystery: A Poem for Europa.” (04:53)

Orbital: An Earth-Centric Novel Set in Space

View the page for this story

The handful of astronauts and cosmonauts on board the International Space Station float in a strange paradox, with the Earth constantly in view, but always out of reach. The 2023 novel called Orbital explores the splendor of planet Earth as seen from orbit through a day in the life of six astronauts up on the ISS, and author Samantha Harvey joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss her book. (15:59)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Stephen Conley, Samantha Harvey, Ada Limón, Robert Zubrin

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Getting humans to Mars is hard but for some, that’s the point.

ZUBRIN: We would get millions of young scientists out of it as we did out of Apollo. Those are the people that create new health cures, new industries, new defense technologies, you name it. The humans to Mars program would once again make science the great adventure.

DOERING: Also, a day in the life of astronauts far from their home planet.

HARVEY: The earth is the answer to every question. The earth is the face of an exalted lover. They watch it sleep and wake and become lost in its habits. The Earth is a mother waiting for her children to return full of stories and rapture and longing.

That’s this week on Living on Earth. Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Methane Tracking From Space

MethaneSAT launched on March 4th, 2024. (Photo: Courtesy of SpaceX, via Environmental Defense Fund)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston this is Living on Earth. I'm Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Today on the show, we’re launching into space.

[COUNTDOWN:… 3, 2, 1… Ignition and Liftoff… ]

O’NEILL: In March 2024, a new satellite with special methane detectors blasted off into Earth orbit.

MethaneSAT, led by Environmental Defense Fund and launched by SpaceX, has the important mission of tracking methane emissions from oil and gas infrastructure across the globe. Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas that can be 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide, so it’s a major contributor to climate disruption. While some private entities are already using satellites to track methane emissions, MethaneSAT is the first initiative to make the information free and accessible to the general public. Dr. Stephen Conley is an atmospheric scientist and the founder of Scientific Aviation, which conducts plane-based measurements of methane and other greenhouse gases. He has worked with Environmental Defense Fund in the past, though he is not involved in MethaneSAT. He joins me now for more. Dr. Conley, welcome to Living on Earth!

CONLEY: Thank you. I'm happy to be here.

An infrastructure tank’s methane flare in Bakken Shale Fields, Mississippi. Methane is a greenhouse gas that is 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide when first released. (Photo: Trudy E. Bell, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O'NEILL: So please start us off with an overview about the project. What are we going to learn from this?

CONLEY: I think what's different about MethaneSAT is this is going to bring much needed transparency to the industries. So it's interesting because if you go back to, say, 12 years ago, nobody was talking about methane, like it just wasn't on the radar. And it was EDF, the Environmental Defense Fund, that really brought methane to the forefront. So they started doing these studies with lots of aircraft flying around. In fact, we did a bunch of their flights, like all over the country. And what they started to do was bring awareness to the methane problem and started this discussion. And one of the challenges that we face is that you need to be able to separate the people in the industry that are doing the right thing from those who aren't, because not all oil companies are created equal--the same for every industry, right? Some landfills are doing a fabulous job of capturing their methane emissions, and some aren't. And so how do you separate them? And what's different about MethaneSAT, and I think what's going to make a profound impact on our emissions, is that all of a sudden, it's that old--was that Ronald Reagan?--"you can run but you can't hide," that now you're gonna have this satellite flying over. And it's actually giving everyone free access to data on who's emitting what, where. And like, right now, we have plenty of satellites that are flying around looking at methane emissions. But they're very expensive to use their data. They're not free. And EDF is making this data publicly available. So everybody's gonna have it. Now, the United Nations has a program where they're monitoring, the International Methane Emissions Observatory. And so I have been talking with them for years, and it's almost gleeful. They're so excited, because at the moment, they're getting most of their data from voluntary reporting. And this is going to sort of be this spy in the sky. It's like, all of a sudden, someone that's watching and giving them the ability to confirm those reports. So that I think is what's going to cause the effectiveness, it's not so much that it's a new technology as it is, it's publicly available.

O'NEILL: And what kind of reactions to this project have you seen from the fossil fuel industry, if any?

CONLEY: So you know, it's interesting, because if you think about it, the companies that are trying to do the right thing, in a way they get put at a competitive disadvantage, when there's sort of no accountability for those that don't, right, because it's obviously less expensive to not do the right thing. And so, both with regulation and with stuff like this, those companies that are taking the right steps are going to be happy about the fact that now there's going to be some public accountability for the fact that we are doing the right thing and others are not, it's gonna help to level the playing field. So I have actually heard good reactions from those companies.

O'NEILL: And what about a major fossil fuel emitter like Exxon or Chevron?

CONLEY: Well, here's a good way to look at this. So there's this organization called the Oil and Gas Methane Protocol [editor’s note: the full title is Oil and Gas Methane Partnership] connected to the United Nations organizations. It's totally voluntary. But as far as I know, all of the super majors, at least the ones that we deal with here in the United States, have joined. So Chevron, Exxon, Shell, ConocoPhillips, they're all part of that, which in itself requires sort of a higher level of attention to the emissions. So I would say, statistically, those super large companies are less of a worry to me than the small ones. Well, one of the typical problems that gets us is that a super large company builds a well, and in the beginning, it's producing tons, it's very valuable. And as that production drops off over the years, ultimately it becomes not profitable to apply their standards to it. And so it ends up getting sold to a smaller operator. And those smaller operators often don't have that level of attention.

O'NEILL: Now, Dr. Conley, you've been working in this field generally for about two decades or so. Why is it that this is happening now, in 2024? What is sort of been a hurdle to it happening earlier?

CONLEY: Oh, a few things. So obviously, one of them is money. There's other operators that have satellites that look at methane, but they had a commercial model. So getting funding was, I don't want to say easy, but it was easier because there was a potential to make a lot of money off of that. Now, EDF had to raise money from people who are just interested in stopping the methane emissions. The other thing I think that's happening simultaneously is the urgency is increasing. So when you see these reports from the Panel on Climate Change, IPCC, where they talk about the timing now that--I think the last one was that we have 12 years to get our emissions under control before we reach the tipping point and it's too late. I think those kinds of statements coming out that stress the urgency are what's sort of driving all this stuff forward in 2024. It's that convergence of funding available and urgent need for change.

Dr. Stephen Conley is an atmospheric scientist, pilot, and programmer. He created Scientific Aviation in 2010 and spent the next decade developing systems for methane emissions detection and quantification. Scientific Aviation was acquired by ChampionX in 2021. (Photo: Courtesy of Stephen Conley.)

O'NEILL: Dr. Conley, what is the big takeaway from this new project?

CONLEY: What this means, bottom line, beyond all the other talk, is transparency. You've got this device that's circling the planet. And all it's doing is telling us when somebody has a problem. When we started doing these flights a decade ago, or actually 14 years ago, it was interesting, because at that time, nobody had flown over oil and gas sites. And so in the beginning, we got a lot of pushback from the property owners, from the operators, saying that you're not allowed to fly over us. And the answer is we are allowed, it's part of the FAA rules. But that brought a level of transparency, because all of a sudden, one of these operators knew that this plane could show up at any time. But they knew the plane was there. That's the difference. With the satellite, you don't know it's there. You're not looking up at the sky and you see the satellite like you do with an airplane. So you've got an operation that's just going on. And the satellite goes over and takes this picture when you weren't even aware of it. Historically, we've had these environmental advocates that would go and they would cut the lock on the site, and they'd go on with their optical gas imaging camera. And then they would send a picture to the New York Times, right, they'd break the law. And so EPA was very clear that you cannot go on to someone's site without permission to get this data that we're going to use in enforcement. While that's not an option, now, if I'm an environmental advocate, all I have to do is start downloading this data from EDF and go match it up to sites, like I can now be just an ordinary citizen, and I can get this data and then go start reporting to the EPA. And so that's where I think that this is going to be so profound in its importance, because every time you have one of these emissions, you're going to be wondering, like, was someone looking?

O'NEILL: Dr. Stephen Conley is an atmospheric scientist and founder of Scientific Aviation. Thank you so much for joining us today.

CONLEY: It was great to be here. Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Learn more about MethaneSAT

- The New York Times | “Tracking an Invisible Climate Menace From 360 Miles Above”

- Read more about methane and its relationship to the climate

David Bowie, “Starman – 2012 Remaster” on The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (2012 Remaster), Jones/Tintoretto Entertainment Co, LLC

Night

Mark Seth Lender turns his camera skyward to capture a lunar eclipse. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

DOERING: If you look up at the sky on a clear night, you can see satellites zipping across a background of stars and planets. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender is usually peering down a camera lens at wildlife but on occasion, he looks up.

Night

© 2023 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

It was clear last night. Unusually clear for down here on the bight. It’s the job of the ocean to put moisture into the air, fog and mist, and clouds. Instead the sky was - blue-black! A color I expect in the mountains or far north. But not here. And it was late and not many lights on along the shoreline. Pristine. I could see the Milky Way. That’s rare, I catch it a few times a year at most. If I see it at all. Usually it’s North to South but it had turned. All the way round to nearly East-West and that I’ve never seen. Jupiter was yellow and huge and low. And many many stars…

I used to look up at those stars and it frightened me, when I was a little kid. I came from a family were knowledge was a valued thing. My father was working on his masters at MIT then, and I remember him coming home with slugs of alloy he’d tested on a hundred ton drop press and he’d show me how the grain, if it was fine, determined that the metal would be flexible and could bend and if the grain was coarse the alloy would crack. That was when I was four years old. When I was seven or eight I knew the stars were far away, that the universe was… Vast. When I thought about that and looked up what I felt was mortal fear.

For Mark Seth Lender, the night sky puts his life in perspective. He finds the vastness of the universe comforting. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Now, instead, the night sky is a comfort. It puts things in perspective. Calms me. I’m learning to name the constellations, something I’ve always wanted to do. I mean like everyone else I know where the Big Dipper is and Orion’s Belt and Cassiopeia (the big W in the sky). But I want, Cignus the Swan, and Camelopardalis and Lynx. And Draco, the Dragon.

Sometimes, the Universe lends encouragement. Two shooting stars right over my head! One left a trail… “WOW! look what I just saw!” Everyone feels that way. Then I thought, where did they come from? Fragments of a distant comet? An asteroid that started out hundreds of millions of miles from here or maybe, as a messenger from a distant star and instead of hundreds of millions of miles, hundreds of millions of years...

We have a place on all this. As much as any interstellar molecule, any distant galactic core.

What a comfort the vastness has become.

DOERING: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender.

Related link:

Mark Seth Lender’s website

Stevie Wonder, “Saturn” on The Complete Stevie Wonder, UMG Recordings

After the break, it takes a lot of trial and error to figure out just how humans could live on Mars.

Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

Gustav Holst, Berliner Philharmoniker, Herbert von Karajan, “The Planets, Op. 32: 2. Venus, the Bringer of Peace, Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Berlin.

A Mars Testing Ground

To simulate a Mars mission, crew members suit up while outside of the station structures. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mars Society)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

In 1976 the Viking I spacecraft landed on Mars and sent back the first high-resolution images of the red planet. And those pictures set off a frenzy of excitement about when humans might get to go there in person to look closer and maybe even discover signs of extraterrestrial life. Nearly 50 years later we’re still working on it. At an average distance of 140 million miles from Earth, it takes a lot of trial runs before we can safely send humans to Mars.

So since 2001, the Mars Society has run roughly 300 simulated missions at a remote site in the high desert of Utah. There they carry out field research, to mimic studies they might run on Mars one day, such as looking for fossilized life. They also monitor the effect of extra-vehicular activity or EVA on the human body. Anyone from around the world can apply to be part of a crew that typically spends 2-3 weeks at the Mars Desert Research Station. Here to discuss is Dr. Robert Zubrin, president of the Mars Society and author of several books on Mars and space exploration. Welcome to Living on Earth!

ZUBRIN: Thank you for inviting me.

O'NEILL: Let's set the scene. If I were to visit the Mars Desert Research Station in Utah, what would I see there? What's it like?

The Mars Desert Research Station challenges crew members to complete a simulated Mars mission under as many Mars-like conditions as possible. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mars Society)

ZUBRIN: The area itself is rather spectacular, red desert, sedimentary rocks, and really a vast area that is uninhabited and almost unvegetated and quite geologically interesting. And then set within this is our station. There's the primary station, which is a habitat craft, it's sort of like a very large tuna can, about eight meters in diameter and six meters tall. So it's got two decks, each with three meters of headroom. And it is modeled on the habitat craft that I designed for the Mars Direct mission. It's what astronauts could fly to Mars in, land on and use as their house on Mars. Then there's additional secondary buildings. There is a greenhouse for growing crops. There is a small science dome. And there's also another small module for doing repairs of equipment in, and then there's a large solar array. So initially, the desert station only included the primary module, and it represented a first landing on Mars. This station as it now is, might be by about mission three, when some additional facilities have been added.

The Greenhab houses both conventional and aquaponic growing systems. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mars Society)

O'NEILL: So what is the purpose of these research stations? You know, what kind of questions are the crews trying to answer?

ZUBRIN: What we're researching is the exploration process itself, okay. We are not researching isolation. There are other people doing missions where they just isolate a crew. Johnson Space Center is going to do a mission like that, the Russians have done missions like that. I think that those missions have a modest utility because the Mars mission is not about isolation. It's about exploration. In other words, what you're going to do when you're on the surface of Mars is field exploration. And what we do is we task our crews to try to do an effective program of field exploration. Most of the crews are just there for two weeks, some as long as three months, while operating under as many Mars mission type constraints as we can impose on them. Essentially, what we're doing in engineering lingo, is we are defining the requirements for the mission: How much water do you need? What is the right kind of exploration vehicle to build? Before you go ahead and spend a billion dollars building an actual Mars exploration vehicle, you want to know what's the right one to design? Okay. And the key thing, the most important step in any engineering process is defining the requirements. It's essential to design things, right, but it's even more important to be designing the right thing. And that's what we're attempting to do.

The Science Dome contains the solar system’s control center as well as a microbiological and geological laboratory. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mars Society)

O'NEILL: And so the goal is to sort of make this mission feel as real as possible as a Martian mission would. To what extent are you able to simulate the Martian environment? It's so different from Earth's, and you're out in this stark, uninhabited desert. But to what extent is it similar to what the Mars landscape itself would be like?

ZUBRIN: Well, first of all, in order to have an effective simulation, you really have to have the crew committed to it, okay, because we've had a couple of crews that did not take it seriously, and just went outside and went walking around, and they came back and said, this was all ***, we just went outside and went walking around. And I said, well, whose fault was that? So you do have to have the crew adopt the mindset, just like in a military field exercise, it's very different from normal war in that no one is actually trying to kill you. But you can get dedicated crews who, you know, act as if the environment was as dangerous as Mars. So for instance, they have to do their field work wearing these simulated spacesuits and communicating to each other by radio and with these thick, heavy gloves that impair your dexterity. And then they have to operate in a telescience collaboration with our mission support group, which is far away. You know, people have heard of telemedicine where the general practitioner Alaska has to do a heart transplant and he's being walked through it by the specialists in Mount Sinai in Manhattan. Well, Mars science is going to have to be done that way. You'll have a few generalists on Mars and they'll be backed up by large science teams on earth and we have to work out this art of telescience. Now, there are some things though, that you can't simulate: Mars gravity.

The vast, remote Utah landscape simulates the surface of Mars. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mars Society)

And this bears on a number of things because a real spacesuit might weigh 150 pounds. Okay, now that's perfectly tenable on Mars because Mars has got 1/3 gravity, so you only feel it weighing 50 pounds. And since your 150 pounds only weighs 50 pounds. Walking around in a marsh spacesuit on Mars. The 300 pounds feels like 100 pounds and there's actually less load on your feet than if you were walking on Earth. But if we stuck the crew in the desert with 150 pound suit, very few of them could even stand up or walk. So We use 40 pound spacesuits to create a load on them that's comparable to what it would feel like on Mars. So there's a assortment of compromises you have to make. And of course, one things that you can't duplicate is the actual danger that you're in. You know, in a in a Mars mission, if your spacesuit was to fail, you would die, okay? Whereas in our mission, if our spacesuit air supply system was to fail, you could just take off the helmet. So there are some differences, but we deal with it as best we can, just as the military rehearses war under non lethal conditions.

O'NEILL: So what is day to day living like for the crews out there that is going to emulate what their lives would be like on this Mars mission?

The MDRS Habitat, or “Hab” is where crew members eat, sleep, and suit up for their daily explorations. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mars Society) https://mdrs.marssociety.org)

ZUBRIN: So everybody wakes up maybe around seven o'clock in the morning. And the plan might be to send three members of the crew out on EVA, while three stay behind in the ham. So after breakfast, the crew goes downstairs and the people who are not going on EVA help the crew into, the EVA team into their spacesuits. And then they get in the airlock, they wait there for 10 minutes to simulate depressurization. And then they go out and they explore. One of the crew members who remains behind is on the radio and is checking in with the EVA team, perhaps every half hour. And then the others, well, they may be doing lab work. In other words, the previous day, they may have brought samples back from the field. And they may be testing them in the lab to try to verify that these are in fact fossils and not minerals, or too if they have found extremely file organisms and micro organisms to image them under the microscope or something. Or they may be engaged in repair of equipment, or someone may go and work a little bit in the greenhouse, something like that. Now the crew out there in the field, they're out roaming around on their all terrain vehicles. And then at a certain point, they get off and they go on foot. And they do direct field exploration, perhaps looking for fossils, or just simply characterizing the geology.

The crew works in the greenhouse. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mars Society)

And then they come back at four o'clock in the afternoon, perhaps, and they're helped out of their suits. And then we always take dinner together. This is extremely useful for bonding the crew, and also talking over what happened that day. And then after dinner, people sit down and write reports and they send reports to mission support. There's a crew commanders report, which is usually very brief, and just outlines what happened that day. We get a science report where people go into more detail on any of the science that was found, engineering report, what systems are working, what are not. And then to me, the most interesting report is what we call the journalist report. And the journalist in this case, is not a person who, like a current newspaper reporter. He is a person more like an 18th century journalist. This is experiential in quality. And they also usually send you know, six or so photographs along with it. And then they send in these reports, and then the crew might sit down and watch a movie together or play a board game or, you know, charades. And then lights out at 11.

Crews generally have dinner together each night in the “Hab” upper deck. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mars Society)

O'NEILL: If I understand correctly, there have been nearly 300 of these simulated missions. And you've commended a number of them yourself. What are your sort of biggest lessons that you've learned over the course of these missions?

ZUBRIN: Okay, number of things. Number one: mission needs to be led from the front by the crew commander with a consultative command style and bringing the rest of the crew into it. Number two, in terms of crew composition, you can have almost any mixture, almost anything will work with the right people and almost anything will fail with the wrong people. And really the crew has to be tested as a team. We've had individuals who were absolute top level crew members in one crew and real problems in others because the chemistry was wrong. And based on studies of US Navy crews in Antarctica, the human factors literature is full of articles concluding that the primary problem is boredom. And that we have to come up with ways to keep the crew busy. In fact, if you take a highly motivated crew, and you send them to Mars, and they're given a chance to do world historic exploration, or even a simulated version of it, like we have in our stations, what you find is that they work themselves hard and the primary human factors problem we get is overwork. Okay, I commanded a number of missions and I had to repeatedly command my crews to stop work at 9pm in order to stop them from burning themselves out.

A crew member works in the lab. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mars Society)

O'NEILL: Wow, yeah.

ZUBRIN: There's various technical conclusions. Before we started this, I thought the best field mobility systems would be pressurized rovers about the size of SUVs. Now I'm convinced based on experience that it would be small, all terrain vehicles, single person vehicles that Mars will be explored in the saddle, you don't want to bring anything to Mars that you're going to take into to the field that you can't lift because it's going to get stuck. We were very interested in looking into how much water the crew would use.

Some crew members take a break to play chess while others work on troubleshooting a 3D printer. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mars Society)

And this is actually a very important number to get because you're going to recycle your water. But how much water do you need to recycle depends on how much water the crew uses. Now what we have found is that you can get by with a sponge bath every other day and a navy shower once a week. If you do this, then your average water consumption, which is not what you drink, that's only a tiny fraction of your water, is about three gallons a day per person, and you can still have an effective crew. Now that's a really important number for designing a Mars mission.

Crew members spend their days in a variety of ways from repairing equipment to writing reports. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mars Society)

O’NEILL: I'm sure you've heard naysayers say, why are we thinking about this? We should focus on Earth. We've got problems here at home. From your perspective, why is it so crucial that we go to Mars?

ZUBRIN: All right, well there's three reasons to go to Mars. And they're for the science, for the challenge, and for the future. Mars was a twin of the early Earth, the early Mars was a twin of the early Earth. They were both warm and wet planets with CO2 dominated atmospheres and rocky surfaces. And we know life appeared on Earth almost soon as it cooled down enough for there to be liquid water. Did it also appear on Mars? If it did, if it happened in two out of two places, then it means it's a high probability event. And it means the universe is filled with life. Because we know from the Kepler space telescope that 20% of all stars in the Milky Way galaxy have an Earth sized planet in their habitable zone, which is the distance where you have the right temperatures for liquid water. So if life occurs naturally wherever you have appropriate physical conditions, life's everywhere, we're not alone in the universe. And these are questions that thinking men and women have wondered about for 1000s of years, and we can solve it by going to Mars.

Part of the crew ventures out into the Utah landscape for field exploration. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mars Society)

Then there's the challenge. A humans to Mars initiative would be a tremendous positive challenge to society, especially the youth, we would get millions of young scientists out of it as we did out of Apollo. During the Apollo program, the United States doubled the number of science graduates, in every level, high school, college, PhD, and in some fields tripled it. And we would benefit from that for decades, okay, because those are the people that create new health cures, new industries, new defense technologies, you name it. The humans to Mars program would once again make science the great adventure.

Dr. Robert Zubrin is the president of the Mars Society and author of “The New World on Mars: What We Can Create on the Red Planet.” (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Robert Zubrin)

And then finally, there's the future. And there's two parts to the future. There's the far future and then there's the near future. Now, if we go to Mars, I am convinced that for instance, 500 years from now, there will be many new branches of human civilization on Mars, but not only on Mars, but further out because Mars is not the final destination, it's the direction. But also you see, there's a near term aspect to this, because it's our vision of the far future that affects what happens in the near future. What's the main threat to humanity today? I think it's pretty clear right now that the threat is war. If we can show that it's not true that there's only so much to go around, okay, because the earth comes with an infinite sky. And by working together, you know, we can create new worlds, so there's no point killing each other fighting over provinces, and by working together, we can open planets. It's not foolproof, humanity can always engage in folly, but at least we can undermine the fundamental argument that supports these catastrophic developments.

O'NEILL: Dr. Robert Zubrin is the president of the Mars Society and author of "The New World on Mars: What We Can Create on the Red Planet." Dr. Zubrin, thank you so much for taking the time with me today. You're most welcome.

Related link:

Read more about the Mars Desert Research Station

Donna Summer, “I Feel Love” on Remember Yesterday, by Giorgio Moroder and Pete Bellotte. Casablanca Records

Life on Europa?

Europa, one of Jupiter’s 95 known moons, is around 90% the size of our Moon. With a water ice crust, scientists have long speculated that there might be a liquid water ocean underneath. (Photo: Juno Mission Photo, Kevin M. Gill, NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

DOERING: Mars isn’t the only promising place in the search for extraterrestrial life. Another big possibility is Europa, one of Jupiter’s many icy moons. Europa has captured the human imagination for centuries: it was first described independently by Simon Marius and Galileo in the 17th century. Nearly as big as our moon, its icy surface makes it a fairly bright object in the night sky, so much so that Galileo could spot it on just a 20-times magnifying telescope. And Aynsley, amateur telescopes these days are often much stronger.

O’NEILL: But Jenni, in the modern day, we’re not simply looking up through our telescopes. We’re sending spacecraft to get up close and personal in the hopes that Europa might show signs that we’re not alone in the universe. Astrobiologists consider liquid water to be an important factor for life, and under an icy crust Europa seems to have almost double the amount that Earth has in its oceans. Water helps sustain vital processes for life from dissolving nutrients to allowing cells to get rid of waste. Two more key ingredients for life are chemical nutrients and energy. Most organisms on Earth get our energy from plants and bacteria that use photosynthesis to harvest light energy from the Sun. But the thick icy crust on top of Europa’s oceans would block the liquid water from receiving the light from the Sun.

DOERING: Huh. So Aynsley, what does that mean for the chances of life on Europa?

O’NEILL: Well, luckily, there are a couple of ways life could still find energy on Europa. One of these actually happens right here on Earth, at the hydrothermal vents at the bottom of our oceans. Europa seems to have a rocky seafloor just like Earth, and if there’s hydrothermal activity there, then organisms could subsist on the chemical building blocks and energy created in that environment. Life might also arise even in a light-starved ocean thanks to Jupiter blasting its moons with energy in the form of radiation.

DOERING: Oh, that’s cool. No wonder we’re taking a closer look!

O’NEILL: Right! Drawn by the possibility that life could exist on Europa, space agencies around the world are turning their eyes and their funding towards further exploration of this icy moon. NASA’s Europa Clipper space probe is set to launch in October of this year. Once it settles into orbit around Jupiter, it will make a series of flybys over Europa’s surface with the goal of studying the moon’s geology and chemical composition and confirming the existence of the liquid water ocean. The Clipper mission lines up with the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, aka JUICE, launched by the European Space Agency in 2023 to look at Europa and two other large icy moons. These missions might one day yield some answers about the potential for life outside our planet. But we’ll just have to be patient since the Clipper mission isn’t expected to reach its orbit until 2030. The cargo includes scientific instruments and a poem dedicated to the mission and engraved on a plaque. Here’s U.S. poet laureate Ada Limón reading her poem “In Praise of Mystery: A Poem for Europa.”

Ada Limón has been the United States poet laureate since 2022. Her poem “In Praise of Mystery: A Poem for Europa” will be engraved on NASA’s Europa Clipper space probe. (Photo: Shawn Miller, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Arching under the night sky inky

with black expansiveness, we point

to the planets we know, we

pin quick wishes on stars. From earth,

we read the sky as if it is an unerring book

of the universe, expert and evident.

Still, there are mysteries below our sky:

the whale song, the songbird singing

its call in the bough of a wind-shaken tree.

We are creatures of constant awe,

curious at beauty, at leaf and blossom,

at grief and pleasure, sun and shadow.

And it is not darkness that unites us,

not the cold distance of space, but

the offering of water, each drop of rain,

each rivulet, each pulse, each vein.

O second moon, we, too, are made

of water, of vast and beckoning seas.

We, too, are made of wonders, of great

and ordinary loves, of small invisible worlds,

of a need to call out through the dark.

DOERING: That’s U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón reading “In Praise of Mystery: A Poem for Europa,” which will blast off with the Clipper mission in October 2024.

Related links:

- Visit NASA’s website for the Europa Clipper mission

- Ada Limón’s “In Praise of Mystery: A Poem for Europa” at the Library of Congress website

Gustav Holst, Berliner Philharmoniker, Herbert von Karajan, “The Planets, Op. 32: 5. Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age, Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Berlin.

Coming up, a novel explores the sixteen sunrises a day aboard the International Space Station.

Keep listening to Living on Earth.

Orbital: An Earth-Centric Novel Set in Space

Orbital by Samantha Harvey is a fictional novel about twenty-four hours in the lives of six astronauts aboard a space station orbiting earth. (Photo: Courtesy of Grove Hardcover)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

At any given moment there are a handful of humans orbiting the Earth aboard the International Space Station. These astronauts and cosmonauts live in a strange paradox. For them the Earth is constantly in view, but always out of reach. They carry photographs of loved ones to keep them close, but these astronauts are still orbiting 250 miles up. Tethered emotionally and by the pull of gravity to the only home our species has ever known, they become each other’s family for six to twelve months. A new novel called Orbital imagines a day in the life of six astronauts up there as they circle the Earth every 90 minutes. Author Samantha Harvey joins us now to discuss. Welcome to Living on Earth!

HARVEY: Thank you, Jenni. It's my pleasure to be here.

DOERING: So Samantha, could you start us off by reading a passage from the beginning of your novel Orbital?

HARVEY: Okay. "Rotating about the earth in their spacecraft they are so together, and so alone, that even their thoughts, their internal mythologies at times, convene. Sometimes they dream the same dreams — of fractals and blue spheres and familiar faces engulfed in dark, and of the bright, energetic black of space that slams their senses. Raw space is a panther, feral and primal; they dream it stalking through their quarters. They hang in their sleeping bags. A hand-span away beyond a skin of metal the universe unfolds in simple eternities. Their sleep begins to thin and some distant earthly morning dawns and their laptops flash the first silent messages of a new day... Some alien civilization might look on and ask: what are they doing here? Why do they go nowhere but round and round? The earth is the answer to every question. The earth is the face of an exalted lover; they watch it sleep and wake and become lost in its habits. The earth is a mother waiting for her children to return, full of stories and rapture and longing. Their bones a little less dense, their limbs a little thinner. Eyes filled with sights that are difficult to tell."

Orbital features descriptions of fictional astronauts performing experiments, reconstituting dehydrated meals, and living an astronaut’s daily routine on a space station. (Photo: NASA, NASA.gov, public domain)

DOERING: In that passage you just read from the introduction, you have this line, "The earth is the answer to every question. The earth is a mother." And one thing I just loved about this book is how central of a role Earth plays in it despite the fact that this is set in space. Most space novels are about escaping Earth's gravitational pull entirely. What made you decide to write a book like this?

HARVEY: Well, I think you sort of hit the nail on the head in that for me, this was always about the Earth more than it is about space. I think it's really interesting and mind blowing to look out at the cosmos and to see it from that vantage point of low Earth orbit. So it wasn't that I didn't find that interesting. But the thing that I wanted to focus on was the view of the Earth, because it's so singular from that vantage point because 250 miles up isn't actually very far, you know. You don't get an entire view of the Earth, you just see the sort of a limb, the Earth's limb, kind of rounding away beneath you. And you can see... not detail. You can't see traces of humanity. And I think that's very interesting. But you can see the natural world. You can see the continents. You can see forests. You can see desert. Obviously ocean, you can see the different types of ocean, that the oceans in different climates across the world, the different colors, the different blues and greens. And I think that distance is both intimate and panoramic and distant. I think is a very sort of kind of paradoxical vantage point to write from. And that's what interested me about it, that it's so intimate, such an intimate view of our planet. You're not far from it, It's kind of tenderly, the space station is tenderly circling this planet. And yet, of course, it's detached from it. It's outside of its atmosphere. It has a different view to any view we could have on Earth. And I think that that contradiction, that sort of bashing together of different perspectives is really interesting to me.

DOERING: Now, Orbital is built around the 16 sunrises and sunsets that these astronauts see in a 24 hour period as they orbit the Earth 16 times per day. And it seemed to me that this structure mimics some of the themes in the book. How did you decide on this really short, narrow timeframe?

HARVEY: Yeah, it didn't come to me at first, actually, that in the first draft, the book was written over a month. And I wrote it from the point of view of just one of the astronauts, and I found that I couldn't say what I wanted to say. I knew that it was a novel I wanted to write, but I couldn't find the means to say the things I wanted, to get to the heart of what I wanted to say. And I was getting bogged down in the repetition of breakfast times and lunchtimes and dinner times over a month. I knew that I wanted to talk about time, the way time has exploded in space. And it occurred to me, after a conversation with a friend actually about the book that I needed to be cleverer about it. I needed to use the structure of the book to say some of things I wanted to say about the dislocation, that disorientation of being in that environment and the fact that you're going around the Earth every 90 minutes. And then it just became perfectly obvious to me that it should be one day, 16 sunset, 16 sunrises that we, as the reader should experience and the book should try in some way to simulate the experience of going around the earth and how one day really just can't feel like one day in many ways. So as soon as I decided on that structure, the whole thing fell into place and everything aligned, and I rewrote it very quickly. And the book shrunk as a result, and it's compressed down to the length it is now which is quite short. So it suddenly began to work. I could make it do the things I wanted to do. I could focus on the imagery, on the sense of time on the dislocating experience of being there without having to contend with endless kind of domestic concerns about their daily schedule over a month.

DOERING: You have this line in your book, "Space shreds time to pieces." I love that.

Astronauts eat food far more typical than the space ice cream found in many museum gift shops. (Photo: NASA, NASA.gov, public domain)

HARVEY: I mean, obviously, I don't know what it's like to be in space. But if you even watch videos of the Earth, of the ISS orbit online, on the NASA website, or YouTube or whatever, you feel this kind of steady progression of the craft around the planet and the rapidity of the sunrise coming upon you. It's dark, and then suddenly, this light rushes across the face of the earth, in a sort of biblical way, that takes your breath away, even watching it on a video, and suddenly it's daylight, and you're in a different continent. And what do you do with that, as someone who's in orbit, experiencing that and when your space agencies are tethering you to a 24 hour clock. And they're trying to structure your days quite rigidly around a 24 hour clock, but nothing that you're experiencing out of the window is reinforcing that. So again, the weird dissonance between the time that is imposed on you from the ground and the time that you're experiencing space creates a sort of weird limbo that you have to somehow function in. So I wanted to imagine what that might be like. And, of course, it is only my imagination.

DOERING: Right? I mean, you know, I've never been up to space. You've never been up there. And yet, you're able to really delve into what it might be like, as an astronaut on the International Space Station. You talk about everyday life and even how they clean the toilets. So how did you go about researching such a unique experience?

Orbital takes place on a fictional version of the International Space Station. In the book, there are six astronauts and cosmonauts from America, Russia, Italy, Britain, and Japan. (Photo: NASA/Roscosmos, NASA.gov, public domain)

HARVEY: Well, actually, it isn't hard to research this subject, because there's so much information about it. I don't know if you've ever spent very long or any time on the NASA website, but is a deep labyrinth of a place. You can spend a lifetime there. And it has so much information about all aspects of what NASA is doing, but particularly the ISS. I read books by astronauts. I watched endless material films and videos made by astronauts. I did countless online tours of the space station. And everything is there to be found out. And then you get the more kind of niche material. I downloaded the ISS Maintenance Manual [LAUGH] and understood, probably 4% of what I was reading. That's probably generous, probably less than that. But I could get a sense of how many moving parts there are and how much maintenance it requires. And then once I was started, I continued to research the subject throughout the writing of the book. So that became a weaving together of research and imagination and allowing the two to sort of exist in a dance together and to constantly feed one another.

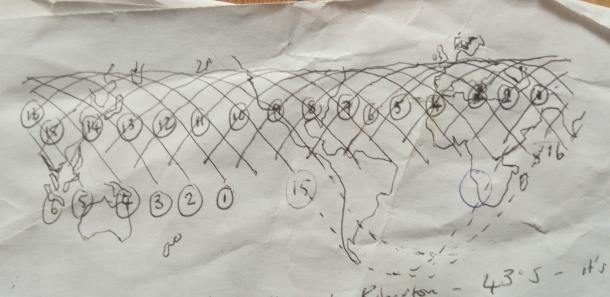

DOERING: And as the astronauts up there orbiting the Earth 16 times a day, they watch this typhoon that's traveling across the Pacific Ocean and building in the Pacific Ocean, and then gathering strength. This is the only disaster that happens in the book. It's on earth, not in outer space. Why was this important to include?

The map of the ISS’s orbit that Samantha Harvey made and referenced while writing Orbital. It was eventually turned into the map included in the front of the book. (Photo: Samantha Harvey)

HARVEY: I wanted something that would kind of mark out time in the book in a straightforward way. So from the beginning, I thought that would probably be a large weather event of some kind so something that is inexorably moving across the earth. And in this case, it's a typhoon that is moving toward the Philippines. Also, I wanted to get to the beauty of some of these weather events from space. And again, the contradiction of that because we know the destruction, they cause on earth but from space they're quite beautiful and mesmerizing. And you can really see the way the weather shifts about the surface of the earth and how the rotation of the earth is pulling the winds and spirals. And I wanted to be able to write about that because it's just actually very inspiring to watch. And also, we know that there are increased weather events, that weather is getting more extreme because of climate change. So I wanted to be able to speak to that without having to make any great claims or lectures on the state of the planet and of climate change. But to be able to say, look, here's something that is happening more frequently. It is something that astronauts see from space quite regularly. It is beautiful; it is magnificent; it is destructive and terrible. And I wanted to be able to hold both of those views in place at the same time, that worldly view and the view from space.

DOERING: It is a really interesting way to be able to observe and sort of comment on what's happening with the earth right now with the climate crisis. Because it is this thing that's so big and huge, that it's usually hard for us to like, even conceive of what's happening. But you're able to narrow this down to a 24 hour period, and to the six astronauts and their perspective. And like watching them, watch this typhoon in the Pacific.

HARVEY: It's hard to know how to think about climate change. It's one thing to sort of intellectually understand what's happening. But to get a grasp on that emotionally or visually, is quite difficult. And I think this was one way of me doing that. And I didn't want this book to be a climate change novel. My motivation was quite different. My motivation was actually to write about beauty and to write about rapture and joy and the splendor of this planet that we live on, you know. I wanted to convey something of what I feel when I look at images of the Earth from space. So I think part of what is implied by looking at the Earth from space and what is implied by its beauty is also the way that beauty is being compromised. And climate change is held within that distanced view of the Earth. It is there to see. And there's a passage in the book in which I sort of talk about that a little bit about how actually, it seems at first, when you look down, it's this kind of humaneness, innocent, unblemished sphere, actually, when you know what to look for, you start to see the signs of mankind, even though you can't see mankind itself, you see signs of it, and of what we are doing to the planet. And that is just a fact of that viewpoint. So it seemed a way of holding the whole view there in front of me at once and just writing about it with a sort of an honesty and sincerity with an eye on its beauty. And to let the rest be implied and to let the reader make of that what they will. And it's just trying to hold a view of the Earth, to the reader to myself, and say, "This is what we have. This is the magnificent thing we have. What do we make of it?"

Samantha Harvey is the author of Orbital and five other books. (Photo: Matt Lincoln)

DOERING: I certainly felt like the Earth is this mother as you write, but it's also really fragile. And it's also this pale blue dot that we can see in this tiny dot in that picture that Voyager took as it turned back towards Earth. At the end of writing this book, how fragile did you feel the earth is? Or did you come away with more of a sense of just how massive and grand it is?

HARVEY: It's interesting when I was writing the book, and I was trying to come up with the descriptions for the earth, you know, obviously things like fragility come up a lot. And it seems like it's made of ether, or it seems like it's made of glass. And it seems rather tiny, because you can orbit it 16 times a day. It's actually not very big. You're in Asia, and suddenly, you're in Australasia, and then suddenly you're in North America, and it hasn't been very long. And the more you watch the videos of these orbits, the more you just become very used to the view. It's like, oh, yeah, there's the East Coast of America. Oh, yeah, there's Central Europe. There's Southern Africa. And it all becomes very familiar, almost like a park, you walk in every day. You come to think of the Earth as quite a small thing. But then at the same time, it's huge. You can't see any manmade objects by day, you know. They just vanish in the immensity of the natural landscapes. And I think in the end, what I came to understand was, the Earth is small, but it's not vulnerable. It's not fragile. It's a lump of rock in space. It will outlive us. We are the vulnerable things — the living things on this planet, the plants, the animals,. It's us we need to think about. I think there's a bit too much talk when we think about climate change of protecting the earth. And I think that's a very abstract way of looking at it. You know, actually, we're trying to protect ourselves and the other creatures that we are fortunate enough to share a planet with. That's what's at stake. We must protect the beings, the... all the living things on this earth, that's our priority. The earth is going to prevail, anyhow.

DOERING: Samantha Harvey is the author of Orbital and five other books. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

HARVEY: Thank you. It was my pleasure.

Related links:

- Purchase Orbital and support both Living on Earth and local bookstores.

- Explore the International Space Station.

- Read more of Samantha Harvey’s work.

Peter Ostroushko with Dean Magraw, “The Nightingale Medley” on Duo, Traditional Ukrainian

O'NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Josh Croom, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

O'NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth