Human Rights in Cancer Alley

Air Date: Week of April 23, 2010

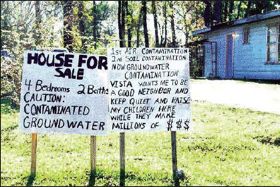

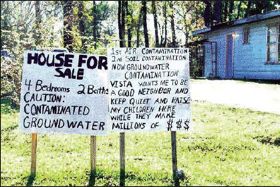

CONDEA Vista settled a suit for $42 million with 80 Mossville residents over a leaky pipe that lead to groundwater contamination. (Courtesy of Advocates for Environmental Human Rights)

The residents of Mossville Louisiana live in the shadow of 14 petrochemical refineries. Community members allege that their high rates of cancer stem directly from these plants. After years of making this argument in American courts they sought a higher judicial body. Now, for the first time ever, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights will hear an environmental human rights case against the United States. Ike Sriskandarajah reports.

Transcript

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. This week the World Media Foundation, which produces Living on Earth is starting something new. It’s called Planet Harmony, and it’s designed to reach out to young people, especially young people of color. Few people of color are actively involved in the pubic discussions about environmental change, even though they have many concerns.

It may be a function of history. For example, in the early days, some national parks were whites-only. But as Earth Day turns 40 barriers are coming down. When Earth Day is 60, fully half of Americans under 30 will be people of color.

Since minorities seldom listen to public radio, we thought we’d reach out through a community based website called My Planet Harmony dot com. There’ll be video and audio – all supported by the National Science Foundation. Living on Earth and Planet Harmony will be sharing stories, like the one you are about to hear now.

YOUNG: Five years ago a group of residents from the rural community of Mossville in Louisiana came to Washington D.C. to file a human rights complaint against their own government. They alleged that the United States was not protecting their right to live in a healthy environment.

View of the Georgia Gulf facility from the home of a Mossville resident. Houses within a one-mile radius have been abandoned or bought out. (Courtesy of Advocates for Environmental Human Rights)

SRISKANDARAJAH: Mossville, Louisiana is old. The village was founded by freed slaves. They chose to settle land with deer to hunt, fish to catch and fertile soil to grow rice and sweet potatoes. Today the descendents of those settlers live in a very different place. Christine Bennett’s family has been living here for four generations.

BENNETT: The place that was once so beautiful and so clean is now a dump.

SRISKANDARAJAH: The petrochemical industry built 14 factories where she lives. They make things like siding for houses and each year release four million pounds of carcinogens such as benzene and vinyl chloride.

BENNETT: What happened to that place that I was reared at—that I can go back and share with my children. This is where my ancestors are. But now part of it is gone, the rest that’s left there is a little ghost town people and starving for life.

SRISKANDARAJAH: We met up with Bennett on her way to file a petition in Washington D.C. on behalf of her community’s human rights. Now, after five years of back and forth with the Government, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights will hear the case.

FARRIOR: Well this case is important in a number of respects.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Stephanie Farrior teaches International Law at Vermont Law School.

FARRIOR: It is the first environmental case coming out of the United States to go to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

SRISKANDARAJAH: So this is the first? So nobody’s tried this before?

FARRIOR: Not from the United States.

SRISKANDARAJAH: But other environmental cases have succeeded. In 1985 The Yanomamo Indians charged the Brazilian government with violating their human rights.

FARRIOR: So that was the first environmental case that came to the Inter-American Commission.

SRISKANDARAJAH: For 50 years the Commission, made up of members from Canada to Argentina, has provided a last line of defense for human rights in the Americas. The United States has been before the Commission on complaints about the death penalty and Indian land claims. But this is the first environmental case from the U.S. to reach the Commission.

The Conoco Phillips oil refinery is one of several facilities that release pollution and dioxins in Mossville. (Courtesy of Advocates for Environmental Human Rights)

SRISKANDARAJAH: Racial discrimination and health impacts of polluted environments have been notoriously hard to win in American courts. Jerome Ringo—former Chairman of the National Wildlife Federation—consulted on another Mossville case. That succeeded in buying up homes of residents closest to a petrochemical factory.

RINGO: Today the first mile from the plant, from the fence line of the plant to a mile into Mossville is abandoned and the property now is owned by the industry and that is contaminated property.

SRISKANDARAJAH: This suit compensated for property damage, but personal health damage…that’s another story. Legal standards make it difficult to pinpoint which of the 14 plants, if any, is to blame for the high rates of cancer in the area.

RINGO: The EPA and the CDC does studies that really check the chemicals that are being discharged by a specific plant, but I am not aware of any study that monitors the chemicals that once they meet into the atmosphere and they mix what do we have then?

SRISKANDARAJAH: This toxic chemical mix is a hallmark of Louisiana’s infamous cancer alley. The emancipated slaves who settled Mossville had land, but no voting rights to protect it.

With the boom in the chemical and plastics industries after World War Two, companies found little resistance to building factories in these disenfranchised, black neighborhoods. Today, government researchers find three times the national average of dioxin levels in Mossville residents.

RINGO: Well you know that’s the responsibility of government. We recognize that we have an EPA, who is now doing great job because of the leadership of Lisa Jackson.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Jackson is the first African American administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency. And she cares about this area.

JACKSON: That’s right. It’s where I grew up.

SRISKANDARAJAH: The administrator has made environmental justice a centerpiece of the EPA. But she says that the laws of the United States still don’t provide adequate protection to its poor and minority populations.

JACKSON: And I think the Mossville case is a really interesting one because what the petitioners argue, as I understand it, is not in order to get heard they had to basically make a case that the laws of this country do not provide them an opportunity for redress.

And it is true that at this point there are no environmental justice laws—there’s nothing on the books that gives us the ability to do it.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Since 1994 a U.S. presidential order has mandated equal protection for minority and low-income populations. But implementation is weak. This isn’t only a problem in North America says Santiago Canton. He’s the Executive Secretary of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

CANDON: We hear that over and over again from people that come to the Commission saying that they try to exhaust local remedies in their own countries, they tried to find justice in their own countries, and they couldn’t find it, so that’s why they come to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

SRISKANDARAJAH: In the coming year the Commission will determine the merits of the Mossville case. This could be a lengthy process as 1,500 petitions are filed every year. But, international lawyer, Stephanie Farrior, says just getting the case heard is a victory.

FARRIOR: The Commission’s decision to let the case go forward really goes to the very foundation of human rights law. Conditions of severe environmental pollution are inconsistent with the right be respected as a human being. And I think that’s what this case is about.

CONDEA Vista settled a suit for $42 million with 80 Mossville residents over a leaky pipe that lead to groundwater contamination. (Courtesy of Advocates for Environmental Human Rights)

Links

A report linking the dioxin levels in Mossville residents to nearby industrial discharge.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth