April 23, 2010

Air Date: April 23, 2010

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Climate Action, At Home and Abroad

View the page for this story

Ten months after the House passed a climate change bill, three Senators are responding with legislation of their own. Host Jeff Young talks with Alden Meyer from the Union of Concerned Scientists about what’s in the bill, and whether the legislation can push strong international action on global warming. (06:00)

Carp Cuisine

View the page for this story

Roughly 600 million invasive Asian Carp have made themselves at home in Midwestern Rivers. As officials struggle to keep them out of the Great Lakes, one local company has a solution. It’s started to ship the carp back to China as food, where they’re considered a delicacy. (04:05)

40 Years Later

View the page for this story

We asked the question – after 40 Years, is Earth Day Still Relevant? -- listeners provide the answer. (01:50)

In Forests, the Challenges of Climate Change and Poverty

/ Mitra TajView the page for this story

REDD-an ambitious plan to pay people to protect rainforests and the carbon stored in them, is beginning to take root in the forests of tropical countries. One of challenges to making it work is the people depend on the forest for survival. Living on Earth's Mitra Taj reports on a pilot project in Indonesian Borneo. (18:00)

Human Rights in Cancer Alley

/ Ike SriskandarakahView the page for this story

The residents of Mossville Louisiana live in the shadow of 14 petrochemical refineries. Community members allege that their high rates of cancer stem directly from these plants. After years of making this argument in American courts they sought a higher judicial body. Now, for the first time ever, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights will hear an environmental human rights case against the United States. Ike Sriskandarajah reports. (07:30)

My Planet Harmony

View the page for this story

This Earth Day Living on Earth launches a new website called My Planet Harmony. This sister show creates a space for young people of color to report on the environmental issues that affect their communities. Host Steve Curwood speaks with Planet Harmony reporter, Ebony Payne, about minority engagement with the environment. (04:30)

Earth Poetry

View the page for this story

It’s also National Poetry Month. To celebrate Ross Gay reads his poem “Thank you”. (01:20)

Earth Day All Over

View the page for this story

From Mexico to Malawi, global voices describe the state of their patch of Earth, and their hopes for Earth Day in another 40 years. (03:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Jeff Young and Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Alden Meyer, Ebony Payne

REPORTER: Mitra Taj, Ike Sriskandarajah

POEM: Ross Gay

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

YOUNG: And I’m Jeff Young. Rich and poor countries clash over climate change. The U.S. withholds some cash meant to help developing nations cope with warming.

MEYER: To say that you’re going to cut off assistance to countries who are suffering the impacts of climate change, largely due to emissions from the United States and other industrialized countries over the last hundred years, I think risks looking pretty heavy handed.

CURWOOD: Also, Mossville, Louisiana. Residents there describe a paradise lost to the petrochemical industry.

BENNETT: What happened to that place that I was reared at—that I can go back and share with my children. This is where my ancestors are. But now part of it is gone, the rest that’s left there is a little ghost town people and starving for life.

CURWOOD: Now little Mossville fights back. We’ll hear that and more this week on Living on Earth. So stick around.

Climate Action, At Home and Abroad

The “tripartisan” push behind new climate legislation: Senators Lieberman (I-CT), Graham (R-SC) and Kerry (D-MA).

YOUNG: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville, Massachusetts—this is Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. It’s a tri-partisan try for action on climate change.

Massachusetts Democrat John Kerry, South Carolina Republican Lindsey Graham, and Connecticut Independent Joe Lieberman have a compromise bill they hope can win in the U.S. Senate.

The House of Representatives narrowly approved sweeping climate and energy legislation last year. But winning over the Senate is far harder.

YOUNG: The Kerry-Graham-Lieberman bill would cap carbon emissions from power plants and encourage cleaner alternatives for transportation. It also supports offshore drilling, nuclear power and coal. Alden Meyer says the bill is a curious combination designed to cobble together 60 Senate votes.

Mr. Meyer directs policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists. He says the Senators are walking a tightrope over tough political terrain.

MEYER: Clearly what they’re aiming for here is a sweet spot, providing enough incentives for those industries to attract some members that normally wouldn’t vote for a climate bill, particularly some of the additional republicans without alienating progressive democratic senators and scaring them away from the bill. So the bill will parallel the house-passed bill in terms of calling for a 17 percent reduction in U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by the year 2020.

It will put a mandatory cap on emissions of the majority of the economy over time. There will be allowances that polluters have to purchase, and of course an open question is, What happens if the senate does take action on this basis, what happens in conference in the house before the bill goes to the president for a signature?

YOUNG: Now, conventional wisdom is that in an election year the actual season for legislation is shortened. What do you think—is this doable in an election year to pass something as difficult as a climate and energy bill?

MEYER: Well, I think it’s definitely doable. Obviously the health care bill is also very difficult, covering a major sector of the economy and they got that through. There’s growing support for action on this because many of the industries, particularly the electric utilities would like to have more certainty about what the future regulatory structure’s going to be as they look to make multi-billion dollar investments in new power generating capacity.

So there’s an increasing number of businesses that are weighing in here, there’s national security arguments for acting on this because of oil imports, and I think everyone agrees that the time is now to do this on the senate floor if senators Kerry, Graham, and Lieberman can attract the necessary support to overcome a likely filibuster.

YOUNG: If this doesn’t work, if the senate can’t pass a climate bill, what happens to the international effort to control climate change?

MEYER: Well, there’s two issues there. One would be, would the administration follow through on the commitment we made in Copenhagen and say that even without legislation we would try to meet that 17 percent reduction goal in other ways, such as through EPA exercising its authority.

The even harder issue would be would we be able to keep our commitment to provide our share of the 100 billion dollars by 2020 that industrialized countries put on the table in Copenhagen for developing country adaptation, clean technology, and reducing deforestation activities.

YOUNG: So if congress doesn’t act, and doesn’t set some price on carbon, then we probably don’t have a ready pot of money to dip into to pay these developing countries the money we’ve promised them. Is that right?

MEYER: Without senate legislation, without a bill in congress that provided some dedicated long-term funding for those purposes it might be very difficult for the administration to keep that part of the bargain. And then I think you might see the whole house of cards fall apart.

YOUNG: Do I understand correctly that the United States has threatened to withhold international aid to countries that we have determined aren’t playing ball when it comes to the way we want to do climate change in the international arena? Is that right?

The “tripartisan” push behind new climate legislation: Senators Lieberman (I-CT), Graham (R-SC) and Kerry (D-MA).

YOUNG: What do you think of that approach?

MEYER: Well, I think it risks being counter productive, I mean to say that you’re going to cut off assistance to countries who are suffering the impacts of climate change, largely due to emissions from the United States and other industrialized countries over the last hundred years I think risks looking pretty heavy handed and actually creating a backlash that won’t meet the goal of trying to get more countries to associate themselves with the accord.

YOUNG: Give me the big picture here. Are we anywhere close to the kind of action that seems necessary based on what we know from the science about the threat of climate change?

MEYER: Well, the answer to that is pretty clearly no. If you look at all the pledges that have been put on the table before, during, and since Copenhagen by the major emitting countries, not just the U.S., but major developing countries as well, such as China, Brazil, India, South Africa, others…collectively, most of the estimates are that those pledges put us on track to limit temperature increase over pre-industrial levels to somewhere between three point five and four degrees Celsius.

The goal that president Obama and other world leaders took on in Copenhagen was to try to limit that temperature increase to less than two degrees. It’s better than business as usual, which probably would have put us on a path to five degrees or over, but it’s not ambitious enough to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

YOUNG: Alden Meyer with the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thank you very much.

MEYER: Thank you, Jeff, good to be with you.

[MUSIC: Trombone Shorty “On Your Way Down” from Backatown (Verve Music 2010)]

Carp Cuisine

Big Head Carp can reach up to 100 pounds. (The Department of Natural Resources)

CURWOOD: The 40th anniversary of Earth Day put the spotlight back on efforts to tackle big environmental problems. Many of today’s challenges are more widespread than those we faced 40 years ago. But budgets are tight as well—so here’s a possible solution for one pernicious problem that could end up making money.

[SOUND OF FISH SPLASHING SHALLOW WATER]

YOUNG: That might sound like rain. But it’s actually fish—hundreds of invasive Asian carp launching themselves through the air along the Mississippi river. The leaping fish have injured boaters—but that the least of the problem. The carp can weigh up to 100 pounds; they crowd out native species and they’re spreading north, threatening the Great Lakes.

Now an Illinois company, Big River Fish Corporation, has an idea to scale back the problem—send them back where they came from. The company just shipped its first load of 40 thousand pounds of Asian carp to China. Big River Fish marketing director Ross Harono starts at the beginning of this fish tale.

Silver carp, one of 11 species of invasive Asian Carp, jump out of the water when disturbed by boat motors. (Courtesy of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources)

YOUNG: So we brought them to the U.S. on purpose?

HARONO: Yes, they were brought in on purpose. They were basically used to clean up the ponds—they eat algae, they’re basically bottom-feeders, so they’re able to help keep the large fish farm ponds clean.

YOUNG: Now, why is the Asian carp such a problem? We have lots of animals that get introduced—why is this one a problem?

HARONO: Well, the problem you have is that they grow ten percent a year in terms of their mass. So that six years ago when I first looked into this problem there were 55 million pounds of Asian carp in the Illinois River basin—now there’s about 100 million pounds because there’s been no natural enemies for these fish, no method of harvesting them, and there has been no, at least domestic, market for these fish.

YOUNG: And I guess that’s what you with Big River Fish Corporation are trying to solve—you want to create that market, right?

HARONO: Absolutely. Asian carp is viewed as a delicacy in Asia. The bones don’t create a problem because we’re used to eating with chopsticks and we spit the bones out. It’s just sort of an educated mouth and tongue in how to eat these fish. And they’re very tasty, so that there is a tremendous demand for this fish in Asia.

Fishermen use nets to catch Asian Carp in Midwestern Rivers. (Courtesy of Big River Fish Corp)

HARONO: That’s part of the marketing strategy is that we’re marketing it as a natural fish grown wild in the Mississippi River and Illinois River that jumps out it has so much energy, so when you eat it you’ll get some of that energy also.

YOUNG: Tell me about the fish because we have such an, I guess, cultural bias against eating carp here in the States—not many people eat carp here.

HARONO: Not many people eat a lot of the bottom-feeders because it’s viewed as fish that’s for the lower class, the poor, and there’s a cultural stigma against eating these fish.

One of the problems we have with these fish—once again there’s a lot of bones—they have these y-bones, which float on the side, 64 of them. So even though you cut a filet out, you end up with these small bones in it. But in Asia, once again, this is not a problem.

YOUNG: Well, this is a very different way of going about this problem because I guess traditionally what the authorities have been doing is trying to poison the Asian carp, trying to build these sort of electronic underwater barriers to prevent them from getting into the lakes—all of these things cost a lot of money. You’re kind of turning a problem on its head and saying, hey, instead of spending money on this, we might make money off this?

U.S. distribution of the Bighead Carp (Courtesy of USGS)

YOUNG: So you’re shipping 40 thousand pounds to China, but you’re looking at millions of pound of this fish in the rivers? Can an operation like this make a dent in the problem of the Asian carp?

HARONO: Absolutely. If we pull out 30 million pounds a year, and that’s our goal, we’ll have the carp situation under control in five years.

YOUNG: Ross Harono telling us about ideas for taking a bite out of the Asian carp problem. Thank you very much.

HARONO: You’re quite welcome.

Related links:

- Big River Fish Corporation

- EPA on the Asian Carp

40 Years Later

CURWOOD: In our show for the 40th Earth Day last week, we asked you listeners whether you thought we still should remember and celebrate it. Well, you weighed in, and didn’t want to pension Earth Day off just yet!

SANDER: I definitely think Earth Day still has a purpose in environmental issues.

JENNINGS: Well, I think that Earth Day is still relevant after all these years. It has an increasingly important role as the consequences of global warming mount. Earth Day keeps these issues in the forefront where they belong, serves as a rallying point, provides unlimited teaching moments, and gives everyone avenues for contribution, participation and action.

ALBANESE: I want to thank you for presenting such a wonderful program. It has reinvigorated my stance on Earth Day. Probably, maybe, we’ll do something a little bit special on Earth Day.

BIGGERS: 40 years after the U.S. failed to sign Kyoto, after a less than satisfactory Copenhagen conference, there’s still a need for Earth Day. Especially for young people, the Earth is our mother, and when she hurts, we all will hurt worse. If young people don’t grab this raging bull by the horns, they may not have an Earth Day worth breathing 40 years from now.

SIPP: Since we only have one planet to work with, having an Earth Day is the right thing to do.

CURWOOD: The views of Nelda Sander of Stillwater, Oklahoma, Pamela Jennings from Grand Rapids Michigan, Gerard Albanese from Kingston Arkansas, Randy Biggers of Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Pete Sipp from Asheville, North Carolina. Thanks to all of you who called or wrote.

[MUSIC The Crusaders “Whispering Pines” from Southern Comfort (Verve Music Group 1974)]

YOUNG: Coming up – we travel to the rainforest of Borneo, where indigenous communities wonder what UN plans to preserve forests mean for them. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

In Forests, the Challenges of Climate Change and Poverty

A fishing village in the forest in Borneo. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

YOUNG: And I’m Jeff Young. The international community seems far from agreeing on a tough plan to prevent runaway climate change. But one potential solution has found broad support. It's REDD—not the color, but a U.N. acronym for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation. It’s a plan to save forests, fight climate change, and help the poor—all at the same time.

CURWOOD: Rich polluting countries like REDD because protecting forest carbon in the tropics could buy time for the reduction of industrial emissions. Developing countries like the billions of dollars REDD could bring them.

But the world’s rainforests aren’t just home to a lot of carbon, they’re also home to a lot of people, and recently—the site of more than 100 REDD pilot projects. Living on Earth's Mitra Taj visited one project in Indonesian Borneo.

Near the river’s edge, the big trees have already been pulled from the forest. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

[SOUNDS OF NOISY GATHERING]

TAJ: Dozens are crowding into a wooden house to discuss REDD in Jelemuk, a village between a big river and a big forest in the heart of Borneo. Most of the people here are Dayak Kantu, a tribe whose roots on the Indonesian archipelago go back more than three thousand years.

[MEETING SOUND]

TAJ: Today Jelemuk villagers have guests: a handful of conservationists, an Australian investment banker, and an American expert on carbon credits.

[MAN SPEAKING ENGLISH]

TAJ: The house belongs to one of Jelemuk’s traditional leaders, but it’s his grown daughter, Ida, who speaks up first:

[IDA SPEAKING INDONESIAN IN MEETING]

VOICEOVER: Everyone here is wondering, who are these white people? We’ve seen you passing through our forests taking leaves and logs but we don’t know what you’re doing. So what is this carbon, anyway? Do you want to take the carbon from our forest, or maybe even gold?!

Ida (left) and other residents of Jelemuk listen as REDD project developers explain avoided deforestation. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

Degraded forests are the source of almost a fifth of global greenhouse gas emissions, and protecting them in places like Indonesia is considered one of the quickest ways to slow climate change. Zoe Harkin, a forest carbon specialist for the conservation group Fauna and Flora International, or FFI, offers this explanation:

HARKIN IN MEETING: If you protect the forest in Indonesia, it makes it less hot in Australia. So we want to help protect forests here so it’s not so hot in Australia.

TAJ: While REDD, or Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation, is still just a four-page document that international negotiators discuss around the world, scenes like these are taking place in tropical forests from Brazil to the Congo.

More than two-dozen REDD pilot projects are in the works in Indonesia—each one an experiment in a brand-new way of managing forests. FFI’s Zoe Harkin:

HARKIN: It is extremely exciting. I mean, I used to work in government and what I would give for a lovely little template that would tell me exactly what I need to do, because you’re constantly feeling your way around, just trying to do the best that you can, but there’s not many or any examples to follow as yet, so that is a challenge.

FFI forest carbon specialist Zoe Harkin (center) and other team members at a community meeting in Jelemuk. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

HARKIN: It really just is early days of trying to introduce the concept of REDD. So if you go from a situation where they’re asking ‘why do you want our carbon’ to giving full permission with full knowledge to undertake the project, it’s just a very long process. And I think they’re very wary of a bunch of white guys coming in and promising all sorts of things because throughout history anytime that’s happened in the past it’s always resulted in a negative outcome for them.

TAJ: Between 1985 and 2004, 14 billion dollars—private and public—poured into Indonesia’s forests. And while the large-scale planting of oil palm and pulpwood trees has helped Indonesia’s companies become industry leaders, the poverty rate for rural Indonesian communities has remained much the same.

[SOUNDS OF FOREST INSECTS AND WALKING THROUGH LEAVES]

TAJ: In Jelemuk, villagers like Ida want a different outcome.

[IDA SPEAKING INDONESIAN]

TAJ: Ida takes her two-year-old daughter by the hand and agrees to show me around Jelemuk. She’s short, wears a bright blue t-shirt, and smiles and laughs a lot.

[IDA LAUGHING]

TAJ: Before heading out into the hot sun, she grabs a large shady hat typical of rice farmers in South East Asia. It’s called “tangguy” and she says all the women here know how to make it.

[IDA SPEAKING INDONESIAN, SOUNDS OF WALKING]

TAJ: She brings me to a tree thick with long thorny pandanus leaves.

[IDA SPEAKING INDONESIAN, TAPPING SOUND]

VOICEOVER: This is the living tree of the hat. We call it purrupo. First you remove the stickers, then you cut it and it depends, if you want to make a hat, you cut it this size, and if you want to make a mat to sleep on, you need to cut it smaller, like this—

[SOUND OF CUTTING STRIPS OF WOOD]

VOICEOVER: And we don’t cut it with a knife, we cut it with fishing line.

[IDA SPEAKING INDONESIAN]

VOICEOVER: Without these hats we couldn’t farm. Working in the sun all day is hard work—we cut down the trees and pull up weeds and burn them so we can plant rice. We have to change plots every year because we can’t afford fertilizer. It’s hard work.

A woman tends to a rice field near Jelemuk. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

TAJ: People in Jelemuk know what they want: a trained doctor in the village, paved roads, and a better future for their children. And they also know what they don’t want: oil palm plantations—the source of a cheap and versatile oil found in everything from oyster crackers to biofuel blends.

Villagers say oil palm companies have taken their neighbor’s land for plantations. Conservation groups like FFI say the industry is responsible for almost half of Indonesia’s deforestation, and FFI wants to use its REDD pilot project to keep oil palms out of Jelemuk’s forest.

But while many hope REDD will empower poor forest communities; some fear it’ll just create another incentive to lay claim to their land, excluding people like Antonius, a traditional leader in Jelemuk, from the one thing he says villagers must have: involvement.

[ANTONIOUS SPEAKING INDONESIAN]

VOICEOVER: We just want to make clear one thing. If FFI wants to make its project happen here, we don’t want to just watch, we want to take part in it. That means asking for permission before doing things to the forest, and asking our opinion about what to do in the forest.

Jelemuk’s traditional leaders, Antonius (left) and Markus. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

TAJ: But it’s not really up to people like Antonius and Ida to decide what happens with their land. In Indonesia, traditional land claims come after national interest, which can be defined as creating jobs, or boosting palm oil exports, or a more recent goal—using REDD to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 26 percent by 2020.

But because global leaders failed to pass a legally binding climate change treaty in Copenhagen, REDD and its preliminary support for local land rights aren’t a reality yet, that leaves the nascent forest carbon market to regulate itself.

(Photo: Mitra Taj)

[IDA SPEAKING INDONESIAN]

VOICEOVER: I am still confused about the idea of carbon trading. I mean, how would it be possible to make it cooler where they live by buying carbon here?

TAJ: The answer involves something Indonesia has a lot of: peat forests.

[WALKING AND TALKING SOUNDS]

TAJ: Gusti Anshari is a scientist hard at work with his crew in a swampy slosh of forest just beyond Jelemuk. His worktable, a blue ice chest settled among moss-covered tree stumps, is splattered in mud and scattered with knives, syringes, and metal blades.

[CLINK OF TOOLS]

Gusti Anshari prepares carbon-rich peat soil for analysis. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

[WRAPPING SOUND OF TAPE]

ANSHARI: This very slow process.

[ANSHARI LAUGHS]

TAJ: Peat is special. If you look closely, you might be able to make out little pieces of fallen forest—twigs, leaves, barks—that haven’t broken down into the soil over the years. That’s because the forest floor is so wet it’s soaking in water. So much water that full decomposition is put on hold. So the plant parts build and build, retaining the carbon dioxide they soaked up when they were alive.

[ANSHARI SPEAKING INDONESIAN]

VOICEOVER: Here, we’re finding the peat is very deep—17 and a half meters deep! So this peat is very unique; we think it was formed 20 thousand years ago.

(Photo: Mitra Taj)

If Fauna and Flora International can keep the oil palm industry out of this undrained forest near Jelemuk, it can sell the carbon as avoided emissions in global offset markets. FFI hired Anshari to find out how much CO2 is in the soil of it’s proposed site.

[ANSHARI SPEAKING INDONESIAN]

VOICEOVER: For this area we predict that there are 15 hundred to two thousand tons of carbon per hectare. It’s a lot of carbon!

TAJ: And when you add in the carbon from the trees and plants growing here, this forest has about 100 million tons of carbon dioxide—the amount of CO2 five million Americans will emit in a year. Preventing those emissions could be worth tens of millions of dollars.

This small river gives villagers fish, clean water, and a path to travel through the thick peat forest. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

[WATER SPLASHING, BOY SPEAKING INDONESIAN]

TAJ: A teenage boy from Jelemuk rows a canoe downriver from where Gusti Anshari is measuring peat.

[WATER SPLASHING FROM ROWING, BOY SINGS]

TAJ: He sings a traditional song about festivities during rice-planting time when the land is cleared and burned, and people play games trying to blacken one another’s faces with the charred remains of the forest.

Villagers gathered in a temporary hut in land cleared for rice and corn cultivation near Jelemuk. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

[BOY SINGS LONGER VERSE]

TAJ: Out here, slash and burn agriculture is one of life’s essentials—in order to eat, you grow rice, in order to grow rice, you clear the forest. But for Fauna and Flora International to successfully market carbon credits from its REDD project, it has to make sure the forest it promises to protect stays protected, and that might mean changing age-old agricultural practices.

[PORT SOUNDS, BOATS AND MOTORCYCLES, TALKING]

TAJ: Puttussibao is the nearest city to Jelemuk, and the Kapuas River is the only way to get here. At the port in the heart of the city, rural villagers from up and down the river arrive in boats, ready to sell their forest products for colorful rupiah bills. Patrick Oswald stands out as a tall lanky blonde German living in Puttussibao.

OSWALD: My part in this is focusing on the aspect of remote sensing, GIS, mapping, carbon accounting.

TAJ: Sent by a German development agency, he’s been helping Indonesian officials prepare for REDD, an effort he calls “slow going.” But he says the bigger challenge isn’t technical—it’s making sure real and reliable benefits flow down the Kapuas River and into forest communities.

OSWALD: People here why they should be environmentalists? Why should they protect the forest so that developed countries can continue with their way of living? People here want to develop themselves. Everybody has televisions—they see how it’s going on, how other people live and they all want a share out of it.

The port of Putussibao at sunset. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

TAJ: But in Indonesia, forest communities’ legal lack of land rights means they’ll probably get the smallest share of REDD revenues. In draft Indonesian legislation, most forests would earn locals 20 percent of total profits—the rest goes to the government and REDD project developers like FFI and its investment partner, the Australian bank Macquarie Group. Oswald says it’s up to FFI to make sure its potential share satisfies both villagers and shareholders.

OSWALD: Of course in the end people must make a living. That’s the point, right? I mean, in the villages they must make a living. On the other hand FFI, they cooperate with Macquarie which is a bank, and of course there are investors in this bank and they see it as an environmental thing but I think primarily they see it as an investment, and as an investment they are seeing how to get some profit out of it.

And from this point of view I think FFI is in a conflict, because FFI must ensure environmental protection, they must ensure poverty reduction, and on the other side they are the investor. I think it’s a very tough job to find middle way.

[SOUND OF WALKING AND TALKING]

TAJ: Back in the forest near Jelemuk, an FFI biologist is showing a Macquarie investor and other visitors how he measures carbon in trees and plants.

[BIOLOGIST SPEAKING, EXPLAINING]

FFI explains how to estimate the carbon-content of trees. By measuring the diameter of their trunks, biologists can determine their weight, about half of which is carbon dioxide. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

HARKIN: One of the trickiest issues is that because we’re associated with a private investor they are very keen to see a return on their investment as soon as possible, and so I have to be honest with you the two timelines cause a lot of tension and we need to be very careful to make sure that the communities are supportive of the project and give intermediate approvals along the way for each of these steps.

TAJ: But Harkin says in order to even get a chance at changing the status quo, a REDD deal needs to happen fast. The government considers the proposed REDD site “production forest” which means it could at any time, write it into an oil palm concession.

[VICTOR SPEAKING INDONESIAN]

TAJ: Constantinus Victor is a local forestry official. I met him in the lobby of the only hotel in Puttussibao.

[VICTOR SPEAKING INDONESIAN]

VOICOVER: 70 percent of the people in this district depend on the forest—for food, for timber. With REDD they could make money from protecting forests, instead of working for an oil palm plantation where they earn low wages and destroy their forests. But oil palm is here and REDD is still a concept. It hasn’t happened yet.

The capital of the Kapuas Hulu district, Putussibau. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

The reason why is simple: oil palm earns more per hectare of land than carbon. Even with mandatory emissions reductions, research shows oil palm out competing carbon credits. Despite all of the challenges, Zoe Harkin says she’s hopeful about REDD’s potential:

HARKIN: Very rarely does an issue internationally get such unanimous support from all the countries in the world— maybe it’s naïve but I feel that it has to succeed with so much support. And for me it’s really the last gasp for the world’s natural forests, and so if REDD doesn’t work, I hate to say it but I don’t think anything will.

[FISHING SOUNDS]

TAJ: Not far from where FFI is measuring carbon, Sabran, a Malay fisherman from a nearby village, tosses a metal net onto the river and watches it fade beneath the water’s surface.

A life tied to the forest; Sabran fishes and taps rubber to survive. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

[SABRAN SPEAKING INDONESIAN]

VOICEOVER: Logging has harmed this forest here, but I still love it because it gives me fish that supports me today and tomorrow. So if there is a way to protect the forest I hope to help make that happen, and I hope everyone will be involved and everyone will feel this places is theirs, and that a sense of belonging will be created.

[SABRAN SPEAKING INDONESIAN]

TAJ: If REDD is to live up to its promise, it’ll have to give power to people who have none, and in places where change comes quickly. For Living on Earth, I’m Mitra Taj in Kapuas Hulu, Indonesia.

[MUSIC: Racoon Fink: “Borneo Is Fallen” from Finally (Racoon Fink Music/Tune Core 2008)]

YOUNG: Coming up: environmental justice—and how the residents of a small Louisiana town are taking the United States to an international court—that’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

Related links:

- For more on forest peoples and REDD, check out the report “The End of the Hinterland: Forests, Conflict, and Climate Change”

- Find news and studies related to REDD in Indonesia here.

- Click here to learn more about Fauna & Flora International and REDD, click here.

- Mongabay stories on REDD.

- The UN REDD website has information on past and current policy developments.

Human Rights in Cancer Alley

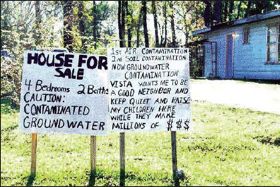

CONDEA Vista settled a suit for $42 million with 80 Mossville residents over a leaky pipe that lead to groundwater contamination. (Courtesy of Advocates for Environmental Human Rights)

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. This week the World Media Foundation, which produces Living on Earth is starting something new. It’s called Planet Harmony, and it’s designed to reach out to young people, especially young people of color. Few people of color are actively involved in the pubic discussions about environmental change, even though they have many concerns.

It may be a function of history. For example, in the early days, some national parks were whites-only. But as Earth Day turns 40 barriers are coming down. When Earth Day is 60, fully half of Americans under 30 will be people of color.

Since minorities seldom listen to public radio, we thought we’d reach out through a community based website called My Planet Harmony dot com. There’ll be video and audio – all supported by the National Science Foundation. Living on Earth and Planet Harmony will be sharing stories, like the one you are about to hear now.

YOUNG: Five years ago a group of residents from the rural community of Mossville in Louisiana came to Washington D.C. to file a human rights complaint against their own government. They alleged that the United States was not protecting their right to live in a healthy environment.

View of the Georgia Gulf facility from the home of a Mossville resident. Houses within a one-mile radius have been abandoned or bought out. (Courtesy of Advocates for Environmental Human Rights)

SRISKANDARAJAH: Mossville, Louisiana is old. The village was founded by freed slaves. They chose to settle land with deer to hunt, fish to catch and fertile soil to grow rice and sweet potatoes. Today the descendents of those settlers live in a very different place. Christine Bennett’s family has been living here for four generations.

BENNETT: The place that was once so beautiful and so clean is now a dump.

SRISKANDARAJAH: The petrochemical industry built 14 factories where she lives. They make things like siding for houses and each year release four million pounds of carcinogens such as benzene and vinyl chloride.

BENNETT: What happened to that place that I was reared at—that I can go back and share with my children. This is where my ancestors are. But now part of it is gone, the rest that’s left there is a little ghost town people and starving for life.

SRISKANDARAJAH: We met up with Bennett on her way to file a petition in Washington D.C. on behalf of her community’s human rights. Now, after five years of back and forth with the Government, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights will hear the case.

FARRIOR: Well this case is important in a number of respects.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Stephanie Farrior teaches International Law at Vermont Law School.

FARRIOR: It is the first environmental case coming out of the United States to go to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

SRISKANDARAJAH: So this is the first? So nobody’s tried this before?

FARRIOR: Not from the United States.

SRISKANDARAJAH: But other environmental cases have succeeded. In 1985 The Yanomamo Indians charged the Brazilian government with violating their human rights.

FARRIOR: So that was the first environmental case that came to the Inter-American Commission.

SRISKANDARAJAH: For 50 years the Commission, made up of members from Canada to Argentina, has provided a last line of defense for human rights in the Americas. The United States has been before the Commission on complaints about the death penalty and Indian land claims. But this is the first environmental case from the U.S. to reach the Commission.

The Conoco Phillips oil refinery is one of several facilities that release pollution and dioxins in Mossville. (Courtesy of Advocates for Environmental Human Rights)

SRISKANDARAJAH: Racial discrimination and health impacts of polluted environments have been notoriously hard to win in American courts. Jerome Ringo—former Chairman of the National Wildlife Federation—consulted on another Mossville case. That succeeded in buying up homes of residents closest to a petrochemical factory.

RINGO: Today the first mile from the plant, from the fence line of the plant to a mile into Mossville is abandoned and the property now is owned by the industry and that is contaminated property.

SRISKANDARAJAH: This suit compensated for property damage, but personal health damage…that’s another story. Legal standards make it difficult to pinpoint which of the 14 plants, if any, is to blame for the high rates of cancer in the area.

RINGO: The EPA and the CDC does studies that really check the chemicals that are being discharged by a specific plant, but I am not aware of any study that monitors the chemicals that once they meet into the atmosphere and they mix what do we have then?

SRISKANDARAJAH: This toxic chemical mix is a hallmark of Louisiana’s infamous cancer alley. The emancipated slaves who settled Mossville had land, but no voting rights to protect it.

With the boom in the chemical and plastics industries after World War Two, companies found little resistance to building factories in these disenfranchised, black neighborhoods. Today, government researchers find three times the national average of dioxin levels in Mossville residents.

RINGO: Well you know that’s the responsibility of government. We recognize that we have an EPA, who is now doing great job because of the leadership of Lisa Jackson.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Jackson is the first African American administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency. And she cares about this area.

JACKSON: That’s right. It’s where I grew up.

SRISKANDARAJAH: The administrator has made environmental justice a centerpiece of the EPA. But she says that the laws of the United States still don’t provide adequate protection to its poor and minority populations.

JACKSON: And I think the Mossville case is a really interesting one because what the petitioners argue, as I understand it, is not in order to get heard they had to basically make a case that the laws of this country do not provide them an opportunity for redress.

And it is true that at this point there are no environmental justice laws—there’s nothing on the books that gives us the ability to do it.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Since 1994 a U.S. presidential order has mandated equal protection for minority and low-income populations. But implementation is weak. This isn’t only a problem in North America says Santiago Canton. He’s the Executive Secretary of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

CANDON: We hear that over and over again from people that come to the Commission saying that they try to exhaust local remedies in their own countries, they tried to find justice in their own countries, and they couldn’t find it, so that’s why they come to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

SRISKANDARAJAH: In the coming year the Commission will determine the merits of the Mossville case. This could be a lengthy process as 1,500 petitions are filed every year. But, international lawyer, Stephanie Farrior, says just getting the case heard is a victory.

FARRIOR: The Commission’s decision to let the case go forward really goes to the very foundation of human rights law. Conditions of severe environmental pollution are inconsistent with the right be respected as a human being. And I think that’s what this case is about.

CONDEA Vista settled a suit for $42 million with 80 Mossville residents over a leaky pipe that lead to groundwater contamination. (Courtesy of Advocates for Environmental Human Rights)

Related links:

- A report linking the dioxin levels in Mossville residents to nearby industrial discharge.

- In 1994 President Clinton made and executive order mandating environmental justice in minority and low-income populations. This order has been difficult to implement.

- Listen to the Living on Earth story filed five years ago when Mossville residents first visited the capital to petition for their human rights.

My Planet Harmony

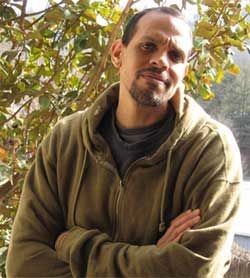

Ebony Payne is a reporter for Planet Harmony.

CURWOOD: Ike is the Senior Editor of Planet Harmony, and everyone is invited to participate in our new online network, and we especially encourage young people of color to share their stories of environmental concern.

Now let’s meet Ebony Payne, she’s a reporter who will be filing stories and blogging from her hometown, Washington D.C.

Welcome Ebony. Hi there!

PAYNE: Hi, how are you?

CURWOOD: Good. And yourself?

PAYNE: I’m good, thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So tell me, why do you think young people of color are getting so involved with the environment these days?

Like with Hurricane Katrina and even the earthquake in Haiti, we’re able to see that these natural disasters have huge implications particularly for our communities and that the government isn’t always quick to respond. With the election of Barack Obama, seeing that we can come together and make big change, I think people of color are just getting really excited to have an impact.

CURWOOD: There’s an increase of interest among young people of color of the environment, but the number seems pretty small. What’s your experience been?

PAYNE: It is small. I used to say it can be pretty lonely being black and being an environmentalist. But it also makes me realize how critical it is to have the voice of communities of color in the discussion because if it’s not then the decisions will be made without us and they are being made without us.

CURWOOD: So, what got you motivated to tell the story of environmental change?

PAYNE: Well, I had an upbringing of playing outside a lot and I was just really sick and tired of seeing my neighborhood trashed. I remember I was walking to school one day and there was this bush and it was just decorated with plastic bags, and I remember thinking that it looked like a Christmas tree with plastic bags as ornaments. But I was just really sick and tired of seeing my neighborhood like it was worth nothing.

CURWOOD: And so then what draws you to telling the story of environmental change?

PAYNE: I think being a reporter it’s a nice way to be able to relate to a lot of different people and to be able to tell everybody’s story. To inspire others. And I think just carrying around a sign, it’s important, but I feel like writing and telling stories is a much more effective way to get the message out.

CURWOOD: So, as a reporter what do you find that young people of color care most about when it comes to the environment?

PAYNE: I would say toxic substances being leaked into their groundwater and into their communities; I would also say the lack of healthy food. If you go into many black neighborhoods, it takes a long time to find healthy fruits and vegetables.

CURWOOD: What are you working on now for Planet Harmony, in terms of a story?

Ebony Payne is a reporter for Planet Harmony.

The legislation deals with over 83 thousand chemicals, five of which are being regulated. And the legislation is trying to change it so that the EPA has more power to regulate and to assess chemicals before they go on the market.

CURWOOD: What do you tell your friends that ask you, hey, how come you’re involved in this enviro-thing?

PAYNE: I feel like it’s the most important issue. I feel like any issue that you care about can somehow be related back to the environment. If you want to talk about agriculture, national defense, health care, public health, make-up and chemicals being in your make-up—anything that you want to talk about, it can be related back to the environment, so I just love that.

CURWOOD: Well, Ebony Payne, I want to thank you for taking this time with us today.

PAYNE: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: And you can check out Planet Harmony on the web by going to myplanetharmony dot com. That’s myplanetharmony dot com.

[MUSIC Timewarp Inc “FunkE” from Dub My Funky Groove (Timewarp Inc 2005)]

Related link:

Add your voice to the environmental conversation at My Planet Harmony.

Earth Poetry

YOUNG: April marks not only Earth Day, but also a celebration of poetry, with National Poetry Month. Here’s Ross Gay.

GAY: This is a poem called Thank you. And I wrote this poem actually in the midst of my father’s struggle with liver cancer. And it sort of came to me while I was dealing with that, and while he was dealing with that. It’s called “Thank You”.

If you find yourself half naked and barefoot in the frosty grass, hearing again the earth’s great sonorous moan that says you are the air of the now and gone, that says all you love will turn to dust and will meet you there. Do not raise your fist, do not raise your small voice against it, and do not take cover. Instead curl your toes into the grass, watch the cloud ascending from your lips, walk through the garden’s dormant splendor. Say only, thank you. Thank you.

[Darcy James Argue “Redeye” from Infernal Machines (New Amsterdam Records 2009)]

YOUNG: As well as writing poetry, Ross Gay teaches creative writing at Indiana University at Bloomington. We found his poem “Thank You,” in the anthology “Black Nature, Four Centuries of African Nature Poetry” edited by Camille Dungy.

Related links:

- Ross Gay’s poem can be found in the book “Black Nature.”

- Click here for more on Ross Gay

Earth Day All Over

CURWOOD: The observance of Earth Day has spread worldwide in its 40 years, along with environmental concerns and action. We asked people from all over the planet to send us audio snapshots of their corner of the globe—and tell us what they hoped to see in another 40 years.

FLESSEL: Hello, my name is Fabienne Flessel. I'm from Guadalope, French West Indies in the Caribbean. Living in Guadalope could be some sort of dream for some people, it is definitely bliss but we have one major crisis in Guadalope, which is due to a product called Kepone, which was used to protect banana plantations from insects, and it got into the water. So there is a higher rate of cancer and they correspond to the places where Kepone was used.

KAONGA: Hi, my name’s Victor Kaonga; I’m based in Malawi’s capital city, Lilongwe. I enjoy seeing green stuff. I enjoy the fresh air that comes with the trees, and I’m very concerned about the country—Malawi’s losing tree cover.

There are so many people involved in cutting down trees. They turn them into charcoal, of course, people in towns by a lot of charcoal because of the infrequent supply of the electricity. So we don’t seem to have a choice.

MARIAM: My name is Mariam and I’m from Iran. I live in Tehran, the capital; many people suffer because of extreme air pollution in this city. There is also the problem of waste. And I work in the field of waste management; I know that the mixed disposal of hazardous waste, along with municipal waste, is an issue of concern in Tehran.

CASTILLO: Hi, I’m Alejandro Castillo from Puerto Peñasco, Sonora that’s in Mexico, just next to the Gulf of California, it’s an area where the ocean and the desert meet and several wildlife and plant species have adapted such as the most endangered marine mammal in the world, the vaquita marina or gulf porpoise. And the biggest problems this region is facing have to do with unsustainable fisheries and tourism development.

[MUSIC: Pat Metheny “Goin Ahead” from Works (ECM Records 1984)]

FLESSEL: What can Earth Day be in 40 years from now? I don’t know it’s just a dream, but I really hope that we could have a look back on the early years of 2000 saying we worked hard enough, we got aware enough of the situation and heard they wouldn’t been necessary anymore.

MARIAM: In 40 years I hope to see the earth free of any kind of pollution and I want to see that all people have access to potable water. I hope the problem of global warming will be solved by complete collaboration of all nations.

CASTILLO: I’d love to be celebrating Earth Day in 2050 eating so much different seafood from the Gulf of California—clams, shrimp, blue crap, gulf grouper, and even the currently endangered totoaba.

If 40 years from now were lucky enough to be able to harvest this species locally it will mean that we have been successful and we’ve learned how to use our resources right. That would definitely be an ideal and delicious Earth Day.

[MUSIC: Nguyen Le’ “Eventail” from Walking On The Tiger’s Tail (ACT Music 2005)]

CURWOOD: Voices from Mexico, Iran, Malawi, and Guadalope, on Earth Day 40 years from now.

Related links:

- For more on the northern Gulf of California’s unique desert-marine ecosystems, click here.

- Fabienne writes about life in Guadaloupe on Global Voices Online.

- Click here to follow Victor’s posts and podcasts from Malawi.

- Learn more about environmental news in Iran here.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Bruce Gellerman, Ingrid Lobet, Helen Palmer, Jessica Ilyse Smith, Ike Sriskandarajah, and Mitra Taj, with help from Sarah Calkins, Marilyn Govoni and Sammy Sousa.

YOUNG: Our interns are Emily Guerin and Bridget Macdonald. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at l-o-e dot org. I’m Jeff Young.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the National Science Foundation supporting coverage of emerging science. And Stonyfield farm, organic yogurt and smoothies. Stonyfield pays its farmers not to use artificial growth hormones on their cows. Details at Stonyfield dot com. Support also comes from you, our listeners. The Ford Foundation, The Town Creek Foundation, The Oak Foundation—supporting coverage of climate change and marine issues. And Pax World Mutual Funds, integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at Pax world dot com. Pax World for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI – Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth