Diluting Dispersant

Air Date: Week of February 4, 2011

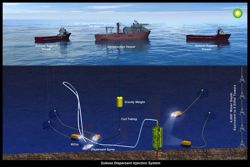

Roughly 1.4 million gallons of chemical dispersant were sprayed on the Gulf of Mexico, and three-quarters of a million gallons were injected directly at the wellhead. (Restorethegulf.gov)

It’s been nine months since the oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico began. More than two million gallons of chemical dispersants were used to break up and degrade the oil. What happened to those dispersants? Nancy Kinner of the University of New Hampshire tells host Bruce Gellerman that the dispersants have been diluted but not degraded.

Transcript

GELLERMAN: Last April, as the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded and sank in the Gulf of Mexico the pipeline snapped at the wellhead, sending 200 million gallons of crude gushing into the water a mile below. BP oil officials, desperate for ways to mitigate the disaster, tried a daring, environmental experiment.

They had workers inject three-quarters of a million gallons of chemical dispersants deep into the underwater plume. It had never been tried before. And only now, 9 months later, do scientists have an idea of what happened to all that dispersant. Nancy Kinner is co-director of the Coastal Response Research Center at the University of New Hampshire.

![]()

This diagram shows how dispersants were injected at the Deepwater Horizon well head. (State of Washington Department of Ecology)

![]()

KINNER: So what happens to the dispersant is it basically has diluted out as this plume of oil has moved away from the wellhead by natural occurring currents. The dispersant has been diluted and diluted and diluted out. The whole idea of the dispersant is it’s going to take the oil and it’s going to help the oil become little droplets of oil that can start moving through the water instead of rising up to the surface, because the surface is where you have most of your productivity – the shrimp, etc.

GELLERMAN: Typically, the solution to pollution is dilution. And, here they’ve diluted this dispersant over a vast area. Is that okay?

KINNER: We don’t know what the impact of this substance, this dispersant material is going to be at low concentrations – very, very low concentrations – over long periods of time. We don’t know that. And so that is something that will, like many things about this spill, will remain to be determined over time.

GELLERMAN: So, here we have this dispersant spread out over vast part of the Gulf of Mexico, can we clean it up?

KINNER: I don’t think that we have any ability to clean up this surfactant at part per trillion, or, now that was in September, it’s probably a lot more dilute now to clean up at those low concentrations. I think it would be impossible, because you’re talking about very, very small amounts over vast volumes of water.

GELLERMAN: But, it didn’t biodegrade? It didn’t kind of break down into its component parts?

![]()

Nancy Kinner is Co-Director of the Coastal Response Research Center at the University of New Hampshire.

![]()

KINNER: It doesn’t appear to have done that based on what they’ve shown.

GELLERMAN: That’s kind of surprising.

KINNER: Well, there are a couple reasons why I don’t think it’s surprising. First of all, remember that the organisms are going to eat what’s easiest to eat. And oil is a much simpler compound to degrade than this surfactant. Okay? It’s like mashed potatoes compared to eating bubble gum.

GELLERMAN: Yeah, go after the potatoes.

KINNER: Go after the potatoes - you’ve got it! And then, the other thing that’s important is not only how edible it is, but also what concentration it’s present in. And so, if you think about this as a plate of mashed potatoes, where you have three pounds of mashed potatoes and you have one tiny little, tiny teeny little piece of ground beef.

GELLERMAN: Uh huh.

KINNER: Well, which one are you going to gear up to eat? Well, you’re going to gear up to eat the mashed potatoes, because there are lots of them. If you have to make enzymes to degrade it you’re going to go for that - you’re not going to go for that one little tiny thing. And so what we find is that when organisms degrade things, it’s not only a function of the degradability of the molecule, it’s also a function of how abundant the molecule is.

![]()

Roughly 1.4 million gallons of chemical dispersant were sprayed on the Gulf of Mexico, and three-quarters of a million gallons were injected directly at the wellhead. (Restorethegulf.gov)

![]()

GELLERMAN: Professor Kinner, if the decision was yours, now, you have another oil disaster in the ocean - would you use dispersants deep below the surface knowing what we know now?

KINNER: I think it would depend on the situation. So, for example, if this was way out in the middle of the ocean - probably not. Because way out in the middle of the ocean, you’re far out from productive coastal waters, that kind of thing, even if the wind blew for days at a time, it probably would not have the oil reach the land.

But if we were talking about a Deepwater Horizon-like situation, where the winds were predominately pushing the oil onshore, and where there was a lot of reproduction going on of key species in the waters and in the marshes, I think the only alternative would be to disperse that oil on the subsurface, because you have so much risk to populations and ecosystems onshore.

GELERMAN: Professor Nancy Kinner is co-director of the Coastal Response Research Center at that University of New Hampshire. Professor Kinner, thank you.

KINNER: Thank you, have a great day.

Links

Click here to see the abstract of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute's report on dispersants

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth