February 4, 2011

Air Date: February 4, 2011

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

UN Stresses Need for Revolutionary Climate Action

View the page for this story

The Secretary-General of the UN Ban Ki-Moon called for “revolutionary action” from global heads-of-state and industries on climate change. Former chief negotiator for the UN climate change talks, Yvo de Boer, tells host Bruce Gellerman about the UN’s new emphasis on sustainable development, and America’s role in it. (06:30)

Diluting Dispersant

View the page for this story

It’s been nine months since the oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico began. More than two million gallons of chemical dispersants were used to break up and degrade the oil. What happened to those dispersants? Nancy Kinner of the University of New Hampshire tells host Bruce Gellerman that the dispersants have been diluted but not degraded. (05:10)

Biomass, Climate Friend or Foe?

/ Mitra TajView the page for this story

The country is looking for alternatives to fossil fuels, and some power companies are seeing a solution in biomass - electricity from the burning of wood and plant materials. While regulators consider biomass a renewable energy source, some scientists say it could be worse for the climate than coal. Living on Earth's Mitra Taj reports on the ongoing debate over biomass' emissions. (07:40)

The Man Working on a Clean Energy Plan

View the page for this story

Host Bruce Gellerman talks with Democrat Jeff Bingaman, chair of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. His committee is charged with legislating a path to a “clean energy” future but he’s not convinced that should include nuclear power, “clean” coal, and natural gas. (05:30)

Science Note - Sharks and Smell

/ Meghan MinerView the page for this story

Researchers discover that sharks use their nostrils independently of one another to find food. Meghan Miner reports. (01:35)

Poo-Gloos

View the page for this story

At a time when rural communities everywhere are scrambling to make ends meet, new igloo-shaped devices have emerged that promise to generate big savings on wastewater treatment costs. According to project supervisor Aart Bahr of Gresham, Wisconsin, “poo-gloos” remove harmful materials from wastewater in an efficient, and cost-effective way. He tells host Bruce Gellerman how they work. (04:00)

BirdNote® Recording Sounds with Gerrit Vyn

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology is among the world’s premier bird organizations. Gerrit Vyn is a producer and photographer for the lab and, in this week’s BirdNote®, he tells of his trials and tribulations of trying to record a Yellow-billed Loon in Alaska’s North Slope. Mary McCann reports. (02:00)

New Moguls of Clean Energy

View the page for this story

An architecture firm in Copenhagen recently won an international competition to design a new power plant for the Danish capitol. The winning plant not only uses residents’ waste to make energy, but also serves as Denmark’s first and only ski mountain. Lead architect, Bjarke Ingels, tells host Bruce Gellerman about the artificial ski slope and why he thinks that industrial buildings should be more playful. (05:00)

The Noisy Ocean and its Conseqences

/ Ike SriskandarajahView the page for this story

Hearing for many sea creatures is as important as sight is to humans. Without sound they can’t tell where they are or who’s around them. And the sounds humans makes in the ocean may be drowning out the regulars. Living on Earth’s Ike Sriskandarajah looks into the science of aquatic acoustics. (07:50)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

In the the village of Dorkas, in northern Greece a shepherd brings his flock in from the fields for the night while listening to a transistor radio.

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bruce Gellerman

GUESTS: Yvo de Boer, Nancy Kinner, Jeff Bingaman, Art Bahr, Gerrit Vyn, Bjarke Ingels

REPORTERS: Mitra Taj, Mary McCann, Ike Sriskandarajah

SCIENCE NOTE: Meghan Miner

[THEME]

GELLERMAN: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth. I’m Bruce Gellerman. Can new technology free us from fossil fuels and save the planet from climate disruption?

DeBOER: The Stone Age didn't end because the stones were finished, it ended because we found something better. And in the same way we need to transition now to modern energy sources - now that is going to hurt for people in the oil and gas business and coal unless we manage to transition that revolution effectively.

GELLERMAN: Coming up - preparing for our energy future. Also, the chips are down - the debate over burning forest waste to make energy - heats up.

BOOTH: The last thing we would want to do is incentivize something as renewable energy that actually makes climate change worse.

GELLERMAN: Biomass, we investigate this burning issue. And sounds from ships and sonar force whales to shout -

[WHALE SOUNDS]

GELLERMAN: Those stories and more just ahead on Living on Earth – stick around!

[THEME]

UN Stresses Need for Revolutionary Climate Action

Ban Ki-moon, Secretary-General of the United Nations at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. (Photo: World Economic Forum)

GELLERMAN: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville Mass, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bruce Gellerman. Despite 20 years of UN led negotiations, global greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase, and a new international climate treaty seems a distant hope. Now the Guardian newspaper in Britain reports that UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon appears to be ending his day-to-day involvement with the climate talks. But he’s not going quietly.

![]()

Former UNFCCC executive secretary Yvo de Boer is now a global advisor for consulting firm, KPMG. (Photo: Greens_Climate)![]()

Ordinarily the UN Secretary is a soft-spoken, genteel diplomat, but at the recent World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland he was outspoken about climate change, inaction and the fate of the planet:

BAN KI-MOON: Climate change is showing us that the old model is more than obsolete. Over time that model is a recipe for national disaster - it is a global suicide pact. It may be strange to speak of revolution but that is what we need at this time.

GELLERMAN: Joining Ban Ki-Moon at the Davos summit was Yvo de Boer – until last year he was the UN’s top climate negotiator. Mr. De Boer, welcome to Living on Earth.

de BOER: Thank you.

GELLERMAN: Strong words from the UN Secretary General, huh?

de BOER: Very strong, but I think that he’s right, that it is a fundamental transformation that we need to be looking at. The global economy is emerging from an economic crisis, and that we’re aware that we’re at a fork in the road. Do we take the brown route and rely heavily on coal, on other fossil fuels, or do we really make the shift to renewables?

GELLERMAN: The UN Secretary General recently made an announcement that signals a dramatic shift. He’s stepping away from the climate negotiations.

de BOER: I don’t think he’s stepping away from the climate negotiations, I think what he’s actually trying to do is, he’s trying to embed the work that’s being done in the climate process so far into national sustainable growth and national green growth strategies. So, really trying to take sustainable growth policy really into the heart of sustainable growth policy, which is ultimately where it belongs.

![]()

Ban Ki-moon, Secretary-General of the United Nations at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. (Photo: World Economic Forum)

![]()

GELLERMAN: But he does say that, ‘I’m not going to deal with day-to-day climate negotiations.’

de BOER: Well, people have said on his behalf that he’s not going to be dealing with day-to-day climate change negotiations and he wasn’t actually doing that in the past. He was very much focused on getting heads of state and government engaged in the process, making sure that we have the political leadership focused on this topic, and I think that’s where he will continue to exert his influence - I certainly hope so.

GELLERMAN: So you don’t think he’s putting his hopes for an international agreement on climate change on the back burner?

de BOER: No, I think not at all. This has been one of his flagship priorities since he came into office, around about four, four and a half years ago, and this topic is very close to his heart. He recognizes that it’s very close to the development agenda. He’s now actually trying to give climate change its proper place in that broader sustainable development agenda.

GELLERMAN: Sustainable development, and he also uses the words ‘clean energy.’ I noticed that in his State of the Union Address, President Obama didn’t mention climate change - he talks a lot about clean energy.

de BOER: Well, the President in his State of the Union Address, it’s true, did not talk about climate change, but he did talk about putting an end to fossil fuel subsidies, to creating green jobs, to stimulating a technological revolution in this country. I think that American presidents as far back as Nixon have been talking about ending an addiction to oil, and maybe it’s time somebody did something about it.

And so, although President Obama didn’t use the words ‘climate change’ I think his agenda in terms of innovation, green jobs, renewable energy and putting an end to subsidies for coal and oil is basically the same thing but using different words- hopefully more popular ones.

GELLERMAN: While you were in Davos, you met with some of the world’s business leaders - and you have over the years - do you have any sense that the people involved in fossil fuel industry are going to step away from the old, or what Mr. Ban Ki Moon calls – the 'obsolete' model?

de BOER: No, they’re not going to step away from that. But to repeat an often made and not very good joke - the Stone Age didn’t end because the stones were finished - it ended because we found something better. And in the same way, we need to transition now to modern energy sources.

Now, that is going to hurt for people in the oil and gas business - and coal - unless we manage to transition that revolution effectively, and that’s all about helping oil and coal industries transform themselves into energy companies that branch out into new areas and into new technologies.

GELLERMAN: Can technology save us?

de BOER: Technology will have to save us, at the end of the day. If we are moving towards a global population of nine billion people that want a decent lifestyle, and we recognize that we can’t give them a decent lifestyle if we continue to rely on the technology today, then we either have to fundamentally shift the technologies that we deploy in a much cleaner direction, or basically sentence billions of people to continued poverty.

GELLERMAN: But can we do that without firm emission targets? Because here in the United States, as you know, firm emissions targets are dead on arrival!

de BOER: Well, firm emission targets are dead on arrival at the federal level. At the same time, I see a lot of states in the country advancing on targets and on emissions trading as well. If all of the states that are talking about emission trading at the moment go ahead with those plans, then close to a quarter of the US economy would actually be under a cap and trade regime.

GELLERMAN: You sound optimistic.

de BOER: Well, I try to be optimistic. I’m frustrated as well. It was a great disappointment, for me, to see that the climate and energy legislation did not make it at the federal level - that President Obama is now having to take a different tack. But at the same time, we are in the situation that all 42 industrialized countries have all set themselves targets for the year 2020 - that 40 developing countries, including two of the big ones, including China and India, have set themselves national targets to limit the growth of their emissions. And those countries count for close to 90 percent of global CO2 emissions. So, in that sense, the train has left the station, unfortunately, it’s moving rather slowly.

GELLERMAN: Can that revolution happen without the United States or will they leave us at the station?

de BOER: The United States has a centuries long history of being a leader in innovation and change and in dynamism. But China is now a world leader in wind and solar technology. And I think that that is for broader economic reasons. And I think that, yes, at the end of the day we could probably do it without the United States, but it would be a great pity to see such a fantastic innovator be left behind.

GELLERMAN: Well Mr. DeBoer I want to thank you again. It’s always so good to talk with you.

de BOER: Very nice to speak with you again. Thank you.

GELLERMAN: Yvo de Boer is a global advisor on climate change and sustainability with KPMG.

Related link:

UN News Center

Diluting Dispersant

Roughly 1.4 million gallons of chemical dispersant were sprayed on the Gulf of Mexico, and three-quarters of a million gallons were injected directly at the wellhead. (Restorethegulf.gov)

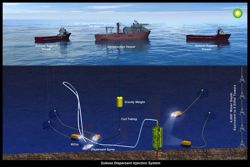

GELLERMAN: Last April, as the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded and sank in the Gulf of Mexico the pipeline snapped at the wellhead, sending 200 million gallons of crude gushing into the water a mile below. BP oil officials, desperate for ways to mitigate the disaster, tried a daring, environmental experiment.

They had workers inject three-quarters of a million gallons of chemical dispersants deep into the underwater plume. It had never been tried before. And only now, 9 months later, do scientists have an idea of what happened to all that dispersant. Nancy Kinner is co-director of the Coastal Response Research Center at the University of New Hampshire.

![]()

This diagram shows how dispersants were injected at the Deepwater Horizon well head. (State of Washington Department of Ecology)

![]()

KINNER: So what happens to the dispersant is it basically has diluted out as this plume of oil has moved away from the wellhead by natural occurring currents. The dispersant has been diluted and diluted and diluted out. The whole idea of the dispersant is it’s going to take the oil and it’s going to help the oil become little droplets of oil that can start moving through the water instead of rising up to the surface, because the surface is where you have most of your productivity – the shrimp, etc.

GELLERMAN: Typically, the solution to pollution is dilution. And, here they’ve diluted this dispersant over a vast area. Is that okay?

KINNER: We don’t know what the impact of this substance, this dispersant material is going to be at low concentrations – very, very low concentrations – over long periods of time. We don’t know that. And so that is something that will, like many things about this spill, will remain to be determined over time.

GELLERMAN: So, here we have this dispersant spread out over vast part of the Gulf of Mexico, can we clean it up?

KINNER: I don’t think that we have any ability to clean up this surfactant at part per trillion, or, now that was in September, it’s probably a lot more dilute now to clean up at those low concentrations. I think it would be impossible, because you’re talking about very, very small amounts over vast volumes of water.

GELLERMAN: But, it didn’t biodegrade? It didn’t kind of break down into its component parts?

![]()

Nancy Kinner is Co-Director of the Coastal Response Research Center at the University of New Hampshire.

![]()

KINNER: It doesn’t appear to have done that based on what they’ve shown.

GELLERMAN: That’s kind of surprising.

KINNER: Well, there are a couple reasons why I don’t think it’s surprising. First of all, remember that the organisms are going to eat what’s easiest to eat. And oil is a much simpler compound to degrade than this surfactant. Okay? It’s like mashed potatoes compared to eating bubble gum.

GELLERMAN: Yeah, go after the potatoes.

KINNER: Go after the potatoes - you’ve got it! And then, the other thing that’s important is not only how edible it is, but also what concentration it’s present in. And so, if you think about this as a plate of mashed potatoes, where you have three pounds of mashed potatoes and you have one tiny little, tiny teeny little piece of ground beef.

GELLERMAN: Uh huh.

KINNER: Well, which one are you going to gear up to eat? Well, you’re going to gear up to eat the mashed potatoes, because there are lots of them. If you have to make enzymes to degrade it you’re going to go for that - you’re not going to go for that one little tiny thing. And so what we find is that when organisms degrade things, it’s not only a function of the degradability of the molecule, it’s also a function of how abundant the molecule is.

![]()

Roughly 1.4 million gallons of chemical dispersant were sprayed on the Gulf of Mexico, and three-quarters of a million gallons were injected directly at the wellhead. (Restorethegulf.gov)

![]()

GELLERMAN: Professor Kinner, if the decision was yours, now, you have another oil disaster in the ocean - would you use dispersants deep below the surface knowing what we know now?

KINNER: I think it would depend on the situation. So, for example, if this was way out in the middle of the ocean - probably not. Because way out in the middle of the ocean, you’re far out from productive coastal waters, that kind of thing, even if the wind blew for days at a time, it probably would not have the oil reach the land.

But if we were talking about a Deepwater Horizon-like situation, where the winds were predominately pushing the oil onshore, and where there was a lot of reproduction going on of key species in the waters and in the marshes, I think the only alternative would be to disperse that oil on the subsurface, because you have so much risk to populations and ecosystems onshore.

GELERMAN: Professor Nancy Kinner is co-director of the Coastal Response Research Center at that University of New Hampshire. Professor Kinner, thank you.

KINNER: Thank you, have a great day.

Related link:

Click here to see the abstract of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute's report on dispersants

GELLERMAN: Just ahead - testing a sewage system that can endure a Wisconsin winter. It's designed like a Russian doll and shaped like an Eskimo home. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

Biomass, Climate Friend or Foe?

Biomass power plants don't have visible emissions pouring from their smokestacks, but the wood they burn can release as much carbon dioxide as fossil fuels. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

GELLERMAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bruce Gellerman. Generating electricity produces about a third of the nation's climate changing emissions. Much of that comes from aging coal-fired power plants.

Now, for the first time ever, the Environmental Protection Agency is taking steps to stem the flow of greenhouse gases from utilities. But NOT those that come from burning biomass - wood chips, forest waste and other plant material. Biomass is widely considered a renewable energy source, but its green credentials are being called into question. Living on Earth’s Mitra Taj reports.

[SQUEAKY NOISE, INDUSTRIAL SOUND UP AND UNDER]

TAJ: Not far from the heart of coal country in Virginia, a power plant is busy churning out the kind of energy that lights up your home, eighty mega watts of electricity—enough to meet the needs of about 20,000 households.

[GENERATOR NOISE]

TAJ: In the boiler room, giant stoves heat water - producing steam - to turn a turbine that creates electricity. It’s the same system that converts fossil fuels into power, but what’s burned here - is wood.

[OUTSIDE SOUND, TRUCKS PASSING AND BEEPING]

TAJ: Just outside the plant, it smells like cut pine, and truck after truck drives into the yard bearing big loads of little pieces of wood. They’re dumped onto a giant pile that’s fed into the plant’s boilers.

HELTON: That’s about seven days of fuel for the plant.

TAJ: John Helton is the station manager for this Dominion biomass power plant near a small town called Hurt. The wood chips, he says, are a byproduct of nearby logging operations. Trees that would otherwise be burnt or thrown out as waste come here.

HELTON: We’re buying the wood that comes in, and they scale in. It has a barcode system, so it’s automatic, and then they scale out. This is the largest biomass plant in the state, and one of the largest in the country.

![]()

At Dominion's Pittsylvania biomass plant in Hurt, Virginia, a truck dumps wood chips into a pile to be burnt to generate electricity. Each truck carries about 22 tons of woody material. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

![]()

TAJ: Dominion bought it in 2004, and is building another biomass plant in southern Virginia now. Nachy Kanfer of the Sierra Club says biomass has caught the eye of power companies like Dominion that are watching as new regulations on pollution turn their inefficient, coal-fired power plants - into liabilities.

KANFER: Coal power is more expensive to run and it’s still just as dirty as before. So, a company like Dominon or like most utilities in this country are looking at their coal fleets and saying—how do we get this coal power offline before it starts really doing damage to our bottom line? So they’re looking at biomass as one possible solution to that.

TAJ: With a few fixes, instead of working with dirty coal, a utility can work with trees. Instead of contributing to climate change, it can be part of a clean energy solution. At least, on paper.

Most regulators treat biomass as a renewable, but some scientists say it shouldn’t be. After all, carbon dioxide makes up about half of most trees, and burning them releases it. Growing trees back to be big enough to suck up substantial amounts of carbon takes decades, and that’s if they’re replanted at all.

Mary Booth, a carbon cycling scientist with the Massachusetts Environmental Energy Alliance, says in practice biomass can be worse than coal.

BOOTH: Trees and forests are really our best defense against climate change right now. Forests currently sequester a large proportion of greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels right now, so cutting those forests and burning them and liquidating that carbon into the atmosphere makes no sense at all from a climate change perspective.

TAJ: The key to whether biomass can be truly renewable is whether the wood burned in power plants would go to waste anyway. If a logging or pulpwood company burns its waste wood as trash or lets it decompose, it’s already emitting carbon dioxide. So no harm done from using the material for electricity. No additional emissions to the atmosphere. But there are no federal regulations that require biomass come from waste wood, and even if there were….

BOOTH: The definition of what is to be considered waste wood is really in the eye of the beholder. And we’re seeing a lot of things defined as waste wood that might otherwise not be considered to be that.

TAJ: Biomass started as a money saver for the paper and pulp industry in the 1980s. Instead of throwing away woody waste, companies started burning it to save on their electricity bills. But today biomass has become crucial to efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions. More than 20 states mandate utilities supply more renewable electricity. There are state and federal tax credits for renewable energy production - and regional cap-and-trade programs on both coasts discourage CO2 emissions.

CLEAVES: It’s widely believed that without biomass we won’t get near our goals.

TAJ: Bob Cleaves is the head of the industry-lobbying group the Biomass Power Association.

CLEAVES: Take the commonwealth of Massachusetts as an example. Right now biomass is 30 percent of that state’s renewable energy supply, and so if biomass were to go away, that would make it nearly impossible not only to meet future targets but you’d see it would set back the effort to green the country’s energy supply significantly.

TAJ: But Mary Booth, who led a study on biomass emissions for the Environmental Working Group, says renewable energy goals mean nothing if emissions aren’t actually reduced.

BOOTH: Indeed, it is discouraging to think that a large fraction of the renewable energy that we’ve been promised we can deploy isn’t going to help with our need to reduce carbon emissions but the best tonic for this is just to deal with the reality and go back to the drawing board and redouble our efforts in other arenas. Because the last thing we would want to do is incentivize something as renewable energy that actually makes climate change worse.

TAJ: Half of the country’s renewable electricity now comes from biomass. There are about 100 plants generating power from biomass in about 20 states, and consumption of biomass power to more than double by 2020.

That biomass is given the same incentives as solar and wind frustrates some environmentalists who fear the growing demand for it won’t just help heat up the planet, it could also wipe out the country’s forests. But Bob Cleaves says that argument doesn’t make any economic sense.

![]()

Biomass power plants don't have visible emissions pouring from their smokestacks, but the wood they burn can release as much carbon dioxide as fossil fuels. (Photo: Mitra Taj)

![]()

CLEAVES: If you were to clear cut forests, causing deforestation, I don’t think anyone thinks that that’s sustainable, and no one would say that’s — quote -- carbon neutral. Fortunately, no one does that. It’s not economically rational to take a tree, chip it and burn it in a boiler, because you would never do that from an economic standpoint. And we don’t think the economics are going to change substantially.

TAJ: Even in a carbon-constrained future?

CLEAVES: Certainly in theory if the country placed a price on carbon that was dramatically different from what people are modeling right now, or if carbon were valued at $100 a ton for example, could that in theory happen? Sure. Do we think it’s going to happen? No. Nor do we encourage it as an industry.

TAJ: The EPA says it needs until 2014 to study the science of emissions linked to biomass before deciding how to regulate them. In the meantime, it can issue permits for biomass plants that will be exempt from greenhouse gas regulations in the future. The agency’s decision has pleased the Biomass Power Association, and the more than two-dozen members of Congress who petitioned the EPA in support of the industry.

Many are swing votes for the kind of clean energy legislation the Obama administration hopes to pass in this Congress, which could, in turn, give another big boost to biomass. For Living on Earth, I’m Mitra Taj.

Related links:

- For more on Mary Booth's work on biomass, click here.

- The Biomass Power Association

- Learn more about the EPA's recent biomass decision.

- Click here to read about how a power company in Ohio backed out of its plans for more biomass.

The Man Working on a Clean Energy Plan

Senator Jeff Bingaman of New Mexico. (Photo: Sierra Suris)

GELLERMAN: Just as defining what’s renewable energy is debatable, so is the question: what’s clean energy? It’s a distinction with a big difference. In his recent State of the Union Address President Obama didn't mention renewable power once - but referred to clean energy no less than 5 times. He wants clean energy to generate 80 percent of the nation’s needs by 2035. The Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources will soon hold hearings on the president’s ambitious goal, and its powerful chairman, democrat Jeff Bingaman of New Mexico, thinks that's doable.

BINGAMAN: It is possible. There is a lot of action going on right now for conventional coal fired power plants that are being scheduled for shut-down. And some of that is just happening because of the economics – the price of natural gas is so low – we don’t have a clear path to get from where we are today to where the President wants us to be, but I think it is conceivable we could get there.

GELLERMAN: The President did mention 80 percent of our energy by 2035 from clean energy -

BINGAMAN: That’s correct….

GELLERMAN: But he defines clean energy a little bit differently, it seems, than you do. You had your renewable electricity standard, and you don’t include some of the things the president does - he includes nuclear power and what he calls clean coal.

BINGAMAN: What we proposed in the last congress, and what we were able to vote out of our Energy Committee, was not a clean energy standard, it was a renewable energy standard, and it said that a certain percentage of the power that was sold by utilities had to come from renewable sources. And that did not include nuclear, it did not include coal, even so called ‘clean coal,’ it did not include natural gas.

![]()

President Obama wants Senator Bingaman to help legislate his goal of doubling the country's clean energy production in 25 years. (Photo: Peter Souza, the White House)

![]()

The President mentioned all three of those in his State of the Union speech. But I’m not proposing any of those at this point – what I am hoping we can do is to hear from some experts, to look at both how a renewable electricity standard operates, and then how that same type of system might work in the case of a broader defined clean energy standard like the President referred to.

GELLERMAN: The President in his State of the Union speech did not mention climate change, or greenhouse gasses - were you disappointed?

BINGAMAN: Well, I think that the President was trying to talk about issues that he would like the Congress to try to move forward and take action on, and send him legislation on. It’s pretty clear that we don’t have the votes in this Congress to pass legislation directly limiting greenhouse gasses. We didn't have the votes to do that in the last Congress - at least in the Senate - and with the change in membership with the new Congress, I think it’s pretty clear that we don’t have the votes in this Congress.

GELLERMAN: The President wants to support clean energy, in part by removing subsidies for big oil. That would be a real drop in the bucket - that’s like four billion dollars - that wouldn’t even be a down payment on some of the projects that, I think, you’re suggesting.

BINGAMAN: Uh, you know, I think that the truth is that the first two budgets that he sent to Congress since he’s been President, they also suggested that the various subsidies for the oil and gas industries be removed or eliminated. The Congress did not take him up on that suggestion. I’m doubtful that this current Congress will either. So there’ll be a struggle to figure out how to get the necessary revenue to do what the President is talking about.

GELLERMAN: Just a few years ago, the United States was a net exporter of green energy technologies and about eight billion dollars in the green, I guess you could put it, and now we’re about 14 billion dollars a year in the red in terms of importing green technologies. What can the US do to improve that?

BINGAMAN: Well, we need to do a whole range of things. And we clearly need to adopt policies that create more of a demand for clean energy products in this country. By doing so, we also attract the manufacturing for those products, and then we are in a position to export - so that’s one thing.

We need to provide more financial assistance to clean energy developers - people who are putting in wind farms and photovoltaic arrays around the country so that we can do better there as well. Other countries have just made this a very high priority. China in particular, has invested an enormous amount - is investing each year - an enormous amount in trying to capture this whole sector of industry - this whole clean energy sector.

GELLERMAN: Well, Senator, thank you very much. I really appreciate it.

BINGAMAN: Okay, my pleasure.

GELLERMAN: Democrat Jeff Bingaman is Chair of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. Right after our conversation he met with President Obama in the White House to discuss energy issues - clean or renewable - we don’t know. Neither the White House nor Senator Bingaman talked to reporters after their meeting.

Related links:

- Click here for a critique of the president's clean energy strategy.

-

Science Note - Sharks and Smell

A hammerhead shark. (Wikipedia Creative Commons)

GELLERMAN: Just ahead – hearing tests - for dolphins - but first, this note on emerging science from Meghan Miner.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

MINER: A state-of-the-art theater with surround sound gives the illusion that audio is just behind you, or to the right, or left. In the grand theater of the ocean, sharks experience surround-smell.

Scientists originally thought sharks used the intensity of smells to locate food. But, because smells don't disperse evenly in water, marine biologists in Florida and Massachusetts wondered if this really was how sharks find their prey.

![]()

A hammerhead shark. (Wikipedia Creative Commons)![]()

The researchers set up an experiment where sharks wore headgear that released scents of different concentrations - one nostril at a time. They found that even when an extremely diluted smell was sent to one nostril before a full strength odor was sent to the other - the shark turned in the direction of the nostril that sniffed the smell first.

This showed that sharks use each of their two nostrils independently to pinpoint their food.

The finding may help explain why hammerhead sharks are considered the fastest and often the first sharks to reach prey. Hammerheads have nostrils on either side of their head, increasing the lag time between scents reaching each nostril - making them faster at honing in on dinner. That's this week's Note on Emerging Science. I'm Meghan Miner.

Related links:

- Researcher Jayne Gardiner’s website

- The article’s abstract/summary in Current Biology

Poo-Gloos

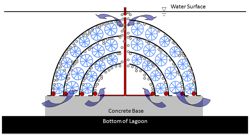

In between the layers of each Poo-Gloo are objects that provide surface area for bacteria to grow. Dirty wastewater enters through the bottom, and after the bacteria remove harmful materials, the water exits through the top. (Courtesy Taylor Reynolds)

GELLERMAN: Like a lot of small towns, the village of Gresham, Wisconsin has a

big and growing problem: an ever tightening budget and an ever-increasing

amount of waste water. So Gresham - population 600 - is trying an experiment for its sewage: a poo gloo. That's "gloo" as in "igloo" and "poo" as in - well, you know. Art Bahr, the Administrator of Gresham, says the makers of the poo-gloo want to see if the igloo shaped device can handle wastewater during a Wisconsin winter.

BAHR: Right now it goes into a lagoon where there’s bacteria, or bugs if you want to call 'em, that eat at the waste and they take and turn that into oxygen and get rid of all the sludge and heavier materials.

GELLERMAN: But in the cold that doesn’t work so well.

![]()

A set of Poo-Gloos waiting to be submerged in a wastewater lagoon.

(Courtesy Taylor Reynolds)

![]()

BAHR: No, in the cold the bugs slow down and don’t like to do their job quite as well.

GELLERMAN: And that’s where these poo gloos come in.

BAHR: Yes. The poo gloos, actually they’re starting to rename them right now - they’re starting to call them biodomes. They wanted to go with a little better terminology for ‘em.

GELLERMAN: Cleaning up their act.

BAHR: Yeah, cleaning up their act in more ways than one.

GELLERMAN: So how actually does a poo gloo work?

BAHR: If you can picture in your mind what a Russian doll looks like - how you can pull the little parts away and there are other little dolls inside.

GELLERMAN: Yeah, the matroshka - the little nesting dolls.

BAHR: Yeah, if you look at that, the top half - there’s seven little nests inside of those domes. There’s seven little smaller domes within it. And in between each of the domes there’s plastic material that the bacteria live on. And, it’s a fixed-film technology. The bacteria live on it, and what we do is we just supply air to them - and the air circulates the water throughout it so the bacteria can eat away at the solids that are in it.

GELLERMAN: So since you have this nesting system, basically what you’re doing is increasing the area - the surface area for the bacteria to grow - you’ve got more area.

BAHR: Yeah, that’s basically what we’re doing. We’re creating a really nice home and a larger home for the bacteria to live.

GELLERMAN: And they work, even in the cold?

BAHR: Yes. They seem to work fantastic in the cold.

GELLERMAN: And how much do these poo gloos cost?

BAHR: They’re about five thousand dollars a piece.

GELLERMAN: Ooh, that’s pretty stiff!

BAHR: It’s stiff, but they’re a long-term item. As long as you treat the bacteria good and give them the environment to live in, they should last for many years.

GELLERMAN: How many of these gloos did you have to buy?

BAHR: Well, right now all we’re doing is we’re just doing a pilot. So, one unit, and everything seems to be working fantastic with this one. Now what will happen is, once we get our data back, it appears that between our two ponds, we’ll have to put in 34 of these poo gloos - we’ll have to put in 17 in each pond.

GELLERMAN: So, at five thousand dollars a pop - a poo gloo - now what is that? A hundred and thirty…thirty thousand dollars?

BAHR: Yes. Now, when you talk about the money of it, we’ve talked about upgrading our ponds to meet the Wisconsin DNR’s statutory requirements for discharge. Now if we do it using older technologies, we’d actually have to put a cover over our pond to keep the pond water warmer - and doing that would cost us approximately 325,000 dollars.

GELLERMAN: Whoa - that’s a pretty stiff bill!

BAHR: Yes, for a small utility, we have two hundred and 75 customers, so we try to do everything economically that we can. We’re the first one in the Midwest to do this - and so the DNR is watching us very closely…

GELLERMAN: The DNR - the Department of Natural Resources - there in Wisconsin?

![]()

In between the layers of each Poo-Gloo are objects that provide surface area for bacteria to grow. Dirty wastewater enters through the bottom, and after the bacteria remove harmful materials, the water exits through the top.

(Courtesy Taylor Reynolds)

![]()

BAHR: Yes, and they’re appreciating all of the data that they’re getting from this. It’s pretty neat that a small town such as ours has a project that could set a trend for a lot of mid-western cold-weather lagoon systems.

GELLERMAN: And it’s not everyday you get to say poo gloo with a straight face.

BAHR: Yes. (Laughs). It’s quite something every time you put it in your computer and it wants to spell it ‘G-L-U-E.’

GELLERMAN: But it’s spelled ‘gloo’. Poo gloo, or biodome, as the makers Wastewater Compliance Systems, prefer. You can see photos of the novel device, and Art Bahr, the Administrator of the village of Gresham, Wisconsin, at our web site L-O-E dot org.

Related links:

- Links: Wastewater Compliance Systems are the makers of Poo-Gloos.

- Watch an above-the-surface walkthrough of Gresham’s pilot Poo-Gloo program.

GELLERMAN: Just ahead – a novel design to turn a waste incinerator into a tourist hotspot - stay tuned to Living on Earth!

BirdNote® Recording Sounds with Gerrit Vyn

Yellow-billed Loon flapping. (Photo: © Gerrit Vyn)

GELLERMAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bruce Gellerman.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

GELLERMAN: Usually sound is part of the background of our stories, but in today's Birdnote we bring it front and center. Lend an ear as Mary McCann offers a sonic bird's-eye view of a day in the life of an avian photographer.

![]()

Yellow-billed Loon on water. (Photo: © Gerrit Vyn)

![]()

[CALL OF THE YELLOW-BILLED LOON]

McCANN: We’re hearing a Yellow-billed Loon calling on Alaska’s North Slope. What does it take to make a recording like this? Here’s Gerrit Vyn, who captured these sounds while on assignment for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

VYN: Trying to record loons has been a really frustrating thing for us to do. The first year when we went up there, I actually spent twelve hours under a piece of camouflage cloth, waiting for Yellow-billed Loons to call, and I had a pair that were swimming right around the microphone and we didn’t get a peep out of them.

![]()

Yellow-billed Loon stretching. (Photo: © Gerrit Vyn)

![]()

MCCANN: Now imagine carrying very specialized battery-operated equipment — along with all your camping gear — across the tundra.

VYN: Basically every step you take, you’re sinking anywhere from your ankle to above your knee in wet, spongy terrain, which can be pretty exhausting, and a lot of times, there’s nowhere dry to put your things down and take a rest.

MCCANN: But the pay-off is there if you’re lucky.

[CALLS FROM A PAIR OF YELLOW-BILLED LOONS]

![]()

Gerrit Vyn recording those Yellow-billed Loons!

(Photo: © Mike Fair)

![]()

VYN: These are a pair of Yellow-billed Loons … they’re giving, they’re going pretty much through their whole repertoire of vocalizations – yodels, wails, and moans. If there’s an invading loon on their lake, they’ll especially get vocal. On this recording, there was another loon that had landed on their lake, and they were trying to drive it off of their lake.

[CALLS FROM YELLOW-BILLED LOONS]

GELLERMAN: Wildlife photographer Gerrit Vyn with BirdNote’s Mary McCann. To see some of Gerrit’s photos of loons, fly over to our website L-O-E dot org.

Related links:

- Call of the Yellow-billed Loon provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by Gerrit Vyn.

- BirdNote® - Recording Sounds with Gerrit Vyn was written by Chris Peterson.

New Moguls of Clean Energy

Onlookers view the smoke rings – every five signify a ton of CO2 has been emitted. (Bjarke Ingels Group)

GELLERMAN: You know what to do when life hands you lemons - but what if it gives you a power plant that burns garbage? Well, if you’re architect Bjarke Ingels of Copenhagen - you turn it into a ski slope. His company, the Bjarke Ingels Group, just won first prize in an international competition that challenged architects to design a new incinerator to turn waste into energy in the Danish capital. Bjarke Ingels joins me on the line from Copenhagen - welcome to Living on Earth.

INGELS: Thanks a lot!

GELLERMAN: So, as I understand it – I’ve seen your drawings and essentially you’re wrapping a ski slope around the smoke stack of this new power plant.

![]()

Onlookers view the smoke rings – every five signify a ton of CO2 has been emitted. (Bjarke Ingels Group)

![]()

INGELS: Exactly like that. This building transforms all the trash of the Copenhageners into electricity and heating - it’s going to be not only the tallest, but also the biggest building in Copenhagen. We thought that since Copenhagen actually has the climate but not the topography for skiing - we could actually provide the Copenhageners with a man-made mountain that transforms the flat but cold, but snowy Copenhagen into a real alpine sort of man-made skiing resort.

GELLERMAN: How many ski trails will you have on this smoke stack mountain?

INGELS: They’re going to be able to choose between a green, a blue and a black slope. It’s also going to contain a mogul slope for the experts and a slope for the kids.

GELLERMAN: But a power plant as a ski slope? I mean, it sounds kind of environmentally contradictory.

![]()

Visitors will enjoy skiing alongside the power plant. (Bjarke Ingels Group)

![]()

INGELS: The interesting thing about this project is that you can say that one of the sort of main drivers of creating a sustainable city is to be able to integrate both the sort of ecological and economical infrastructure of the city into the city fabric itself.

So you somehow need to find a way of actually integrating these really big industrial facilities in the middle of the city. So, the challenge of the competition was to make a big factory beautiful. And we thought of just wrapping it in just beautiful wrapping - we would really turn the entire plant into a gift for the citizens of Copenhagen.

GELLERMAN: So people are going to take a lift or gondola to the top of the plant and then ski down?

![]()

A view of the power plant at night. (Bjarke Ingels Group)

![]()

INGELS: It’s actually…they’re going to take traditional vertical elevators, just like…unlike normal mountains where you are forced to take ski-lifts, here you can actually take a vertical elevator all the way from the ground to the roof. And, the slope, because in this case it’s a man-made mountain, we can engineer it so all the slopes end up straight at the foot of the elevator.

But also as the power plant is going to be interested in displaying its deployment in environmental technologies in the transformation of waste into heat and energy - they’ll also be able to take like a promenade and actually sort of explore the various operations of the factory looming inside the mountain.

GELLERMAN: I was reading about the award, and I see that this stack is going to puff out smoke rings.

INGELS: We thought that it could be interesting to transform the smokestack itself into a sort of a playful element. Just like the factory becomes sort of a ski slope, the way we designed the chimney is that the mouth of the chimney is in the shape of a giant disk - the hollow space inside the thickness of this disk gradually fills up with smoke, and when it changes 200 kilos of CO2, this chamber compresses and it blows a giant smoke ring.

One of the main ideas is of course to turn the symbol of the factory, the chimney, which is also the symbol of pollution, into something playful, but I think more importantly, one of the main drivers of behavioral change is knowledge. If people don’t know they can’t act. In the future, like in 2016, when this plant has been realized, I’ll be able to tell my kids that once they’ve counted five smoke rings, we will have emitted one ton of CO2.

This sort of abstract element of a tale of smoke - that’s like ungraspable and uncountable suddenly becomes very basic just like, you know, counting the seconds after you see the lightning flash. You know, just counting the smoke rings you’ll be able to tell how much CO2 we’ve emitted.

![]()

The side of the building will be green as well. (Bjarke Ingels Group)

![]()

GELLERMAN: Do you remember sitting around a table with your design team and saying - ‘you know, I’ve got a great idea.’ What did they say to you when you came up with this idea?

INGELS: I mean, they gradually realized when we started probing and digging into all the criticism and all the sort of complications, that this was like, almost like the only sensible thing to do with something as big as a giant power plant.

And, it was only when we sort of came up with the notion, not only sort of training a building that has an economical and an ecological purpose, you know, it recycles waste into energy - but to give it a social purpose that actually this giant volume becomes a part of the topography of Copenhagen, and contributes to the citizens of Copenhagen and turns it into a destination.

![]()

The incinerator will have slopes for expert and novice skiers. (Bjarke Ingels Group)

![]()

Because if sustainable is always perceived as the question of, like, how much of our existing quality of life are we prepared to sacrifice in order to afford being sustainable - essentially the sort of moral burden that we have to bear - the sort of general understanding that it has to hurt to do good - we try to look at some different approach where sustainable cities and sustainable buildings actually increase the quality of life. We call this ‘hedonistic sustainability.’

GELLERMAN: Well, Mr. Ingels, goodluck with your waste-to-energy ski slope in Copenhagen.

INGELS: Thanks a lot. And you’re very much invited to come and test it out with a pair of skis on your feet in 2015.

GELLERMAN: (Laughs). I’ll be there. That's Danish architect Bjarke Ingels, whose award-winning incinerator will produce electric power - and skiing pleasure.

Related link:

Learn more about the project at the Bjarke Ingels Group’s website:

The Noisy Ocean and its Conseqences

(Photo: David Mann)

[OCEAN WAVES]

GELLERMAN: For us, this is the sound of the sea. But creatures that live under the waves have a totally different soundscape - one that human activities have made increasingly noisy. And the cacophony could be disturbing sea life that depends on sound to survive. Living on Earth's Ike Sriskandarajah prepared our report.

[MOVIE CLIP: JACQUES COUSTEAU DOCUMENTARY: Le Monde du Silence]

SRISKANDARAJAH: Jacques Cousteau called the ocean “The silent world,” and he gave that name to his 1956 underwater documentary.

Le Monde du Silence by Jacques Cousteau and Louis Malle gave us the first color video of the deep sea.

GENERIQUE CINEMA - LE MONDE DU SILENCE 1955

Uploaded by generique-cinema. - Discover the latest sports and extreme videos.

[JAQUES COUSTEAU: "LE MONDE DU SILENCE"]

SRISKANDARAJAH: But while it's mostly silent to us - to its regular residents, the ocean can sound like a busy street corner. And research from two ocean scientists, shows us the significance of sound in the sea.

[OCEAN SOUNDS, BIRD NOISES]

SRISKANDARAJAH: The first study comes from David Mann, an associate professor of biological oceanography at the University of South Florida. He recorded these bottlenose dolphins around Tampa Bay.

[DOLPHIN SONAR NOISES]

MANN: Yeah, it’s an underwater recording - it’s in the middle of the night. Everything you hear in there is completely natural sound. There’s a dolphin whistling at high frequency, and then there are fish sounds - which most people don’t know about that are lower frequencies. The fish sounds are like…ba ba ba ba ba.

[FISH SOUNDS]

![]()

If beached dolphins are deaf, Mann says that releasing them back into the wild is a death sentence. (photo: David Mann)

![]()

MANN: And so it’s interesting for people for a number of points. One is that, you know, there’s a lot of animals in the ocean using sound for communication.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Mann says every dolphin has its own signature whistle. That’s how a baby dolphin identifies its mom through all other calls around it. Just like if we met and I’d say, ‘hi! I’m Ike!’

MANN: For example, the bottlenose dolphin’s whistle is saying like, ‘Bob, Bob, Bob, Bob,’ you know, my name.

[DOPHIN CALL]

SRISKANDARAJAH: But whistles aren’t just to identify which dolphin is Bob. They also tell them where they are and what’s around. Being able to hear is vital. For dolphins, deafness is disorienting.

MANN: In the dolphin’s world, if you even have a 40-decibel hearing loss, your range of echolocation is going to drop by a hundred fold. And that’s basically making the animal blind.

SRISKANDARAJAH: For five years, David Mann would rush to the beach whenever he heard of a stranded dolphin. And he would give the dolphin a hearing test.

MANN: Yes, and it is completely non-invasive. It’s the same exact test that they use with human infants to test for deafness. And so, the one difference is, you know, we don’t have headphones, per se, for dolphins. We use what we call a jaw-phone, which is simply a small speaker in a suction cup.

SRISKANDARAJAH: The dolphin would have a speaker on its jaw and a suction cup on the top of its head to monitor brain waves. The brain waves show up as a line on a little portable screen.

MANN: They’ll play a sound to you like ‘boop, boop, boop.’

[HEARING TEST SOUND]

![]()

David Mann and his team administer a hearing test to a rough-toothed dolphin named Sleepy. Dolphins hear through a fat pad on the lower jaw. The light blue suction cup is a “jawphone” and the other two suction cups measure brainwaves. (photo: David Mann)

![]()

SRISKANDARAJAH: In a healthy dolphin, the brainwaves go wild at that tone. But a lot of the time, David was staring at flat line.

MANN: You know, the first time we though our equipment wasn’t working. Because it’s basically that you’re not getting any electrical response off the brain when you play sound to it. But then we started seeing this, you know, more then one time, and we also had animals at the same location that had normal hearing, so…

SRISKANDARAJAH: Over the five years Mann and his team conducted these tests, they found that more than half of the bottlenose dolphins that beached themselves had significant hearing loss. But he thinks that just might be part of being a dolphin.

MANN: Deafness is common in humans, and so there’s no reason to suspect that dolphins are going to be any different than humans.

SRISKANDARAJAH: But there’s another possibility. Human-made sounds might be hurting their hearing in ways we don’t understand.

![]()

David Mann checks for brain activity in a dolphin’s auditory cortex. The portion of a dolphin’s brain dedicated to hearing is relatively larger than a human’s, and should be very active. (photo: David Mann)

![]()

MANN: If you start running hundreds of thousands of ships on the same shipping channel back and forth, you know, all of the time, and you raise the background noise like 30 and 40 decibels on average continuously, now you’re affecting lots and lots of animals. And it’s happening out in the ocean so it’s a lot harder to actually figure out what the effects are.

SRISKANDARAJAH: David Mann isn’t the only scientist wrestling with that question - so is Susan Parks.

PARKS: So that’s the joy of science.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Parks is an assistant professor of acoustics at Penn State. She studies how ocean noise might affect one of the oceans largest and rarest inhabitants - the Right Whale.

PARKS: Right. So Right Whales are endangered and there are about 400 left in the north Atlantic now.

SRISKANDARAJAH: They’re so rare now because they were the ‘right’ whales to hunt. And man is still the danger.

PARKS: These whales are living in an area that’s highly influenced by human activities- similar to animals that live in the city. Most things that people might do in the ocean, either intentionally or inadvertently, produce sound as a byproduct.

[BOAT MOTOR NOISE, SONAR PINGS]

PARKS: The one that we think about a lot with the species that I study are the sounds generated from commercial shipping.

[BOAT HORN]

PARKS: It’s only been about a hundred years that these ships have been in the ocean. And then if you look at the number of ships, the number of ships have been steadily increasing - in particular - over the past 40 or 50 years.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Parks wanted to know how that had affected Right Whales.

PARKS: One of the simplest ways to do this was to look at recordings from the 1950s when there were fewer ships in the ocean to ones made in, sort of, modern time, when there was a higher level of background noise.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Go to the tape. The first was recorded in 1956, the same year Jacques Cousteau called the ocean the silent world. The tape made by William Schevill of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, is a little scratchy.

[SOUNDS OF THE OCEAN FROM 1956]

SRISKANDARAJAH: Fifty years later, Parks made another recording of Right Whales at the bay of Fundy where Maine meets Canada.

[WHALE SOUNDS, MODERN DAY]

![]()

Since right whales can live 65 years, Parks says it’s possible that the whales William Schevill recorded in the 50’s are the same whales she recorded in 2006. (photo: Susan Parks)

![]()

PARKS: The main difference between the two recordings, and if you listen to it… you can hear that the sounds produced by right whales in the 1950s, there’s actually been a shift upwards of about 30 hertz for this species.

SRISKANDARAJAH: What’s that - like - an octave?

PARKS: Uh, a little less than an octave, yeah.

SRISKANDARAJAH: So, today, are Right Whales more…. falsetto?

PARKS: (Laughs). Well, still, it’s all pretty low frequency.

SRISKANDARAJAH: So they sing higher to cut through the ship noise, and they also sing louder. As we ratchet up our volume, so do the whales. But perhaps there’s a limit.

PARKS: It’s possible that when the noise level exceeds a certain threshold, they just stop calling.

[MUSIC FROM JACQUES COUSTEAU DOCUMENTARY]

SRISKANDARAJAH: And Parks says that could make the lonesome leviathan even more solitary.

![]()

Susan Parks sends her acoustic recorders to the bottom of the Bay of Fundy to record right whale vocalizations. (photo: Susan Parks)

![]()

PARKS: Individuals don’t make a lot of calls - they’re relatively sort of a strong, silent type. In an endangered population, this is particularly of concern because there are fewer individuals out there. They’re in the same ocean and they need to find each other to mate, and to relocate their offspring.

SRISKANDARAJAH: But how these whales will actually cope with an increasingly noisy world is still an open question.

PARKS: So, you’ve sort of gotten to the heart of why I actually…why I study whale communication. We don’t know!

[MUSIC FROM JACQUES COUSTEAU DOCUMENTARY: Le Monde du Silence]

SRISKANDARAJAH: But we do know that the ocean never was Cousteau’s ‘Silent World.’ Life in the ocean has always been noisy. But now there are four billion more people then there were in 1956. With all of the decibels human trade and industry generate at sea, navigating through the din is the 21st century challenge for ocean creatures.

[MUSIC: YO LA TENGO, THE SOUNDS OF THE SOUNDS OF SCIENCE.]

SRISKANDARAJAH: For Living on Earth, I’m Ike Sriskandarajah.

Related links:

- Individual right whales call louder in increased environmental noise:

- Hearing Loss in Stranded Odontocete Dolphins and Whales :

[SOUNDS OF SHEEP’S BELLS TINKLING]

GELLERMAN: We leave you this week in northern Greece - in the village of Dorkas, not far from the Bulgarian border. At dusk, a shepherd brings his flock in from the fields for the night. But listen carefully. As the sheep got closer, recordist Steven Feld heard some static and a news broadcast. Only then did he notice a transistor radio poking out of the shepherd's pocket. These and other sounds can be heard on his CD "Bells & Winter Festivals of Greek Macedonia."

[SOUNDS: Bells & Winter Festivals of Greek Macedonia (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings 2002). Track 2 - Belled Sheep of Dorkas.]

GELLERMAN: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Ingrid Lobet, Helen Palmer, Jessica Ilyse Smith, Ike Sriskandarajah, Mitra Taj, and Jeff Young, with help from Sarah Calkins, and Sammy Sousa. Our interns are Sean Faulk and Wynn Tucker. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE dot org – and while you’re online, check out our sister program, planet harmony. Planet Harmony welcomes all and pays special attention to stories affecting communities of color. Log on and join the discussion at my planet harmony dot com. And don’t forget to check out the LOE facebook page, it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. Steve Curwood is our executive producer. I'm Bruce Gellerman. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the National Science Foundation supporting coverage of emerging science. And Stonyfield farm, organic yogurt and smoothies. Stonyfield pays its farmers not to use artificial growth hormones on their cows. Details at Stonyfield dot com. Support also comes from you, our listeners. The Ford Foundation, The Town Creek Foundation, The Oak Foundation—supporting coverage of climate change and marine issues. And Pax World Mutual Funds, integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at Pax world dot com. Pax World for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI – Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth