US Reactor Safety In Light of Fukushima

Air Date: Week of September 6, 2013

Fukushima Reactors 3 & 4 after meltdown of 3 began. ( Wikimedia Commons)

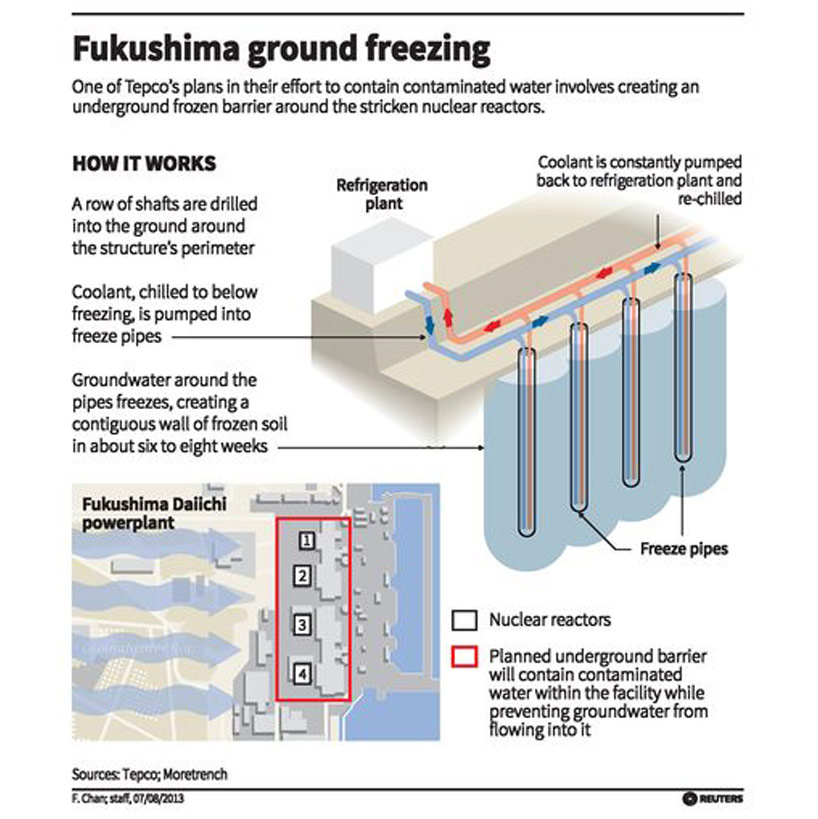

Japanese authorities are unable to control the radioactive water leaking out of the damaged Fukushima nuclear power plant. Now the government plans to install a wall of ice around the facility to contain the contaminated water. Ed Lyman, from the Union of Concerned Scientists, tells host Steve Curwood that the new ice wall plan is likely an act of desperation, and that some American reactors are at risk for the same kind of flooding disaster.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. The news coming out of Japan about attempts to clean up the wrecked Fukushima nuclear power station and contain the tons of radioactive water leaking into the ground and the Pacific Ocean is not reassuring.

A diagram demonstrates how coolant will be used to freeze the soil in a wall around the Fukushima nuclear facility and prevent ground water from coming in contact with radioactive waste. (Tepco)

Now the Japanese Government is pledging nearly half a billion dollars to try to freeze the ground under the melted down reactors, to try to control the leaks that way. It sounds like a desperation play, so we turned to a senior scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, Edwin Lyman, to find out whether this could work, and what the condition of the plant is at the moment.

LYMAN: The situation seems to be pretty bad and it's getting worse. The plant is leaking radioactive material every day into the ocean, and right now the plant’s operator Tepco is unable to stop it.

Fukushima Prefecture is featured in red. (Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Now the Japanese government says they want to build a wall of ice around the reactor. How would that work?

LYMAN: The idea is, you would create essentially, artificial permafrost. The idea is to embed pipes about 100 feet deep in a ring around the damaged reactors and run coolant through those pipes, so essentially you’re running a refrigeration unit that would slowly freeze the soil and would turn into an impenetrable block of ice.

CURWOOD: How long would the ground need to be kept frozen? To what extent would generations in the future still be trying to keep the refrigeration running?

LYMAN: Well, that really depends on the timeline for actually cleaning up and stabilizing the site so we’re talking about potentially decades.

CURWOOD: I think people are not familiar with this icewall technology you’re talking about. How common is it? And at what scale?

LYMAN: It is a technology that has been used in other applications for a long time, particularly during mining excavation, but has not been used on a large scale to deal with a situation this delicate involving radioactive material, and not for the kind of time scale we’re talking about. So in effect it really is uncharted waters in regards to Fukushima.

CURWOOD: And by the way, where does the electrical energy come from to freeze all that soil? I understand that Japan shut down the vast majority of its nuclear power plants.

A large area around the Fukushima nuclear facility will be uninhabitable for generations.

LYMAN: Yes, the irony is they will need a significant amount of power to operate this refrigeration system, and right now Japan depends heavily on imported natural gas for a lot of its electricity.

CURWOOD: Now I know the government utility Tepco has tried some other options to contain the leak, but everything seems to come up short. This wall of ice kind of sounds like an act of desperation. What’s your take on it?

LYMAN: I think that’s a good description. There aren’t any good options in dealing with this mess. You just have to come up with a way to divert groundwater so that it does not run through the site and pick up radioactivity, and there are only a few ways you can do that, digging trenches and filling them with some sort of impermeable material. Ice is one option, but it seems to be, I would think, a slightly more unstable option because you do need to maintain active cooling for a long period of time.

CURWOOD: Now the same time that things are going on at Fukushima, Entergy Corporation has announced plans to cost the Vermont Yankee nuclear power plant next year. Why are they doing that?

LYMAN: The economics of nuclear power in the United States is very precarious right now. The price of natural gas is extremely low, primarily because of the availability of gas from fracking. And the nuclear power plants that are running today are simply unable to compete in many cases because of the ongoing operations and maintenance costs just to run nuclear power plants safely.

CURWOOD: What about the experience at Fukushima? Has the nuclear regulatory commission in the United States changed the safety rules as a result of that accident?

LYMAN: Yes, the nuclear regulatory commission has made certain changes and introduced some new requirements for reactors, especially the type of plant at Fukushima, which is the same as Vermont Yankee, a General Electric Mark 1 Boiling Water Reactor, and more changes are in the works. And even though the industry has tried very hard to limit the scope of those changes, there still is a significant price tag associated with them. And Entergy did cite the cost of post-Fukushima upgrades as one of the reasons why they’re shutting the plant down. Frankly, to have nuclear power that’s safe enough so that don’t have another Fukushima simply may not be affordable.

CURWOOD: Where in the United States are there nuclear power reactors in analogous positions to Fukushima...in other words vulnerable to earthquakes and such?

LYMAN: Well, I think in United States, the biggest threat is actually from upstream dams. There are a few dozen plants on rivers or lakes, which are vulnerable in the event of a dam failure, to being flooded in a very short period of time, as happened in Fukushima. And the nuclear regulatory commission has known about the danger of dam failures for many years, but it has been taking a very, very long time to try to resolve these issues.

CURWOOD: Where are these dams that you’re concerned about?

LYMAN: One plant which is the most vulnerable is called the Oconee in South Carolina. There are three reactors there, and the plant’s owner, Duke Energy, has been sparring with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission about how to reduce the flooding from dam failure. Still unresolved. The industry simply isn’t prepared to deal with nuclear accidents, before they happen or their aftermath, and it’s that lack of preparation, and that mindset that we don’t have to worry, it can’t happen here, that I think continues to pose danger to people all over the world.

CURWOOD: Ed Lyman is senior scientist of the Global Security Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thanks so much, Ed, for taking this time.

LYMAN: Thanks for the opportunity.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth