September 6, 2013

Air Date: September 6, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

House Climate Hearings Set for 9/18

View the page for this story

Since 2010, Representative Henry Waxman (D-CA) has been asking the Representatives to take on climate change . Now the GOP House majority have finally set climate hearings for September 18. But Representative Waxman tells host Steve Curwood that the Republican hearings are not exactly what he hoped for. (06:35)

Republican Climate Hearing Agenda

View the page for this story

The House of Representatives is gridlocked on climate change, with Republicans skeptical of the science. The Heritage Foundation's climate, energy and economics analyst David Kreutzer tells host Steve Curwood that despite their decision to hold hearings, Republicans aren’t changing their position on climate, and question government spending . (05:30)

US Reactor Safety In Light of Fukushima

View the page for this story

Japanese authorities are unable to control the radioactive water leaking out of the damaged Fukushima nuclear power plant. Now the government plans to install a wall of ice around the facility to contain the contaminated water. Ed Lyman, from the Union of Concerned Scientists, tells host Steve Curwood that the new ice wall plan is likely an act of desperation, and that some American reactors are at risk for the same kind of flooding disaster. (06:30)

Pink Salmon In Trouble on the White River

View the page for this story

In the Pacific north-west, stocks of pink salmon have rebounded strongly. But on the White River, thanks to tight federal budgets, many fish get stuck at an old dam, and are dying in the attempt. From the public media collaborative EarthFix, Ashley Ahearn reports. (04:40)

Why Fish Have Different Amounts of Mercury

View the page for this story

Deep sea fish tend to accumulate more mercury than those that swim in shallower waters. A recent study from the University of Michigan explains that sunlight plays a major role in detoxifying the mercury found in fish tissue. Lead author Joel Blum joins host Steve Curwood to discuss how he traced mercury from the atmosphere into Pacific fish. (05:00)

Tough Neighbors--Coopers Hawks

View the page for this story

Getting to know your neighbors is a pleasure of life in the South of the US. But as commentator Pat Priest of Athens Georgia observes, some neighbors can both charm and repulse us. (03:30)

Data Gaps For Chemical Safety

View the page for this story

An explosion at a chemical fertilizer plant in West, Texas earlier this year killed 15 people and injured more than 150. Daniel Lathrop, a staff reporter for the Dallas Morning News, tells host Steve Curwood that no one really knows how often accidents like the one in Texas occur, because nobody's keeping track. (06:25)

Mortgage Lifter Tomatoes

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

Reporter Jeff Young learns the history of one of his favorite tomatoes: Radiator Charlie's Mortgage Lifter. The man who developed the famed tomato had a life as colorful as the plant that bears his name. (07:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Henry Waxman, David Kreutzer, Edwin Lyman, Joel Blum, Daniel Lathrop, Reporters: Ashley Ahearn, Pat Priest

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. As Japanese authorities plan to freeze the earth around the wrecked Fukushima reactors to contain radioactive water, experts say some US nuclear facilites could be just as vulnerable to a similar catastrophe.

LYMAN: There are a few dozen plants on rivers or lakes which are vulnerable in the event of a dam failure to being flooded in a very short period of time as happened at Fukushima.

CURWOOD: Also, science has found out why some fish are more likely to contain the more toxic form of mercury.

BLUM: When it forms near the surface of the ocean, sunlight breaks down the methyl mercury back to its common form and essentially detoxifies it. But deeper in the ocean where there is no sunlight this process doesn’t take place.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm. Makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

House Climate Hearings Set for 9/18

Obama’s climate change speech in June, 2013, targeted C02 emissions, particularly from coal-fired power plants (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Back in June, Barack Obama called on the EPA to begin regulating CO2 emissions from existing power plants, which emit 40 percent of US global warming gases. The executive order came in response to a 2007 Supreme Court ruling and years of climate gridlock in Congress.

California Congressman Henry Waxman and other House Democrats have been calling for hearings on the science of climate change ever since Republicans won control of the lower house in 2010.

Now leaders of the House Energy and Commerce Committee have summoned representatives of 13 federal agencies for climate change hearings on September 18. You might expect Henry Waxman to be pleased, but he has mixed feelings.

WAXMAN: Well, I think the upcoming climate hearings is a positive development, but it’s not a signal of change of direction in Congress. The Republicans are in control. They’ve denied the science, and they don’t want the administration to act, and they certainly don’t want Congress to act.

Representative Henry Waxman of California’s 33rd district (photo: United States Government)

So they’re bringing in people from the different agencies in government who are proposing regulations on their own under existing law which gives them the authority to do it, and I think they’re going to berate them. How can you talk about doing something to limit pollution from coal burning power plants? What authority do you have to do that? Why is the Department of Energy doing something to limit the efficiency of refrigerators?

I expect that’s what they’re going to do because that’s the way they’ve acted for the last three or four years. They’ve denied the science. They don’t think there’s a problem, and they voted over 53 times to say that we shouldn’t be doing anything about the climate change issue.

CURWOOD: A cynic might say that the Republicans are calling in all these agencies and departments to scrutinize their budgets involving climate with a view towards trying to cut those budgets.

WAXMAN: They’ve already proposed cutting those budgets. They proposed cutting the budgets of all the government agencies that do any kind of regulation - also government agencies that do research. But I think they want to show their oil and coal industry constituents that they’re standing up to this administration, and I think we’re seeing an indication this is just a beginning of an escalating outcry by the Republicans where the government acts on its own under authority of the law to limit carbon and other greenhouse gases that cause climate change.

CURWOOD: Now what’s the format of these hearings?

WAXMAN: They’ve invited a lot of witnesses. I think they’ll put them at a table, and each one will get five to ten minutes to make their comments, then we’ll ask questions back and forth - Republicans first, Democrats after that, then back to Republicans.

CURWOOD: Who will testify?

WAXMAN: I haven’t heard precisely who’s going to testify, but the head of the EPA is Gina McCarthy, Dr. Moniz is the Secretary of Energy, both of course have testified before our committees and subcommittees many times.

CURWOOD: Well, how much climate science will be discussed? Both Gina McCarthy and of course formerly Professor Moniz are well versed in the science of climate change.

WAXMAN: Well, they are indeed, and we could ask them and probably will, to talk about the science that motivates them to take the actions that they’re taking, but we ought to hear from other researchers, we ought to hear from other scientists.

The overwhelming consensus is that not only are we seeing the impact of climate change - which costs us billions and billions of dollars in damage - but that we’re only seeing the beginning of it because the problem is accelerating and getting much worse than anybody quite imagined, and Republicans won’t allow a hearing from the scientists, and that isn’t because they haven’t been asked.

Congressman Bobby Rush is the ranking Democratic on the energy subcommittee and I have written over 28 separate letters requesting a hearing, and you know how many answers we’ve gotten to our letters? None. And so the Republicans are in charge and you wouldn’t think there was a problem of climate change if you listen to what they have to say.

CURWOOD: Congressman Waxman, what does this say about Americans’ ability to deal with public policy implications of science if one particular party is not willing to hear what scientists have to say?

WAXMAN: In the past, I think people had a reverence for science because it’s not partisan - it’s based on evidence, it’s testing a hypothesis based on realities of what we’re seeing, what conclusions the evidence points to. But Republicans - some Republicans - have approached science as another point of view as if it’s part of a political discussion. I think that’s a serious mistake.

This isn’t the only instance where we’ve seen science denied or distorted. I remember when President George W. Bush was in office, his Department of Health and Human Services put on the web that women who got abortions were more likely to get breast cancer. And we raised a fuss about it asking them what scientific evidence did they have to make such a statement? Of course, they had none. They just made it up because it fit with their ideology.

So we’ve seen a disregard for science on the environmental side, we’ve seen it on the reproductive rights issues. They think science is something to be used if it fits their ideology, not trying to figure out the best policy based on the evidence and proceeding from there.

Senator Moynihan once said, you can have different opinions, but you can’t have different facts. And Republicans are trying to make different facts by ignoring the evidence.

CURWOOD: So on these climate hearings in front of the House Subcommittee, what do you expect will come out of all of this?

WAXMAN: Well, I hope these hearings will be positive. I think it’s positive because we’re talking about the climate issue, and I wish it were a signal in the change in direction that Congress - in the House anyway - wants to pursue. But at least we’ll hear from the administration that’s made a determination under President Obama to take action, not just to watch the consequences and pretend they’re not real.

CURWOOD: Henry Waxman’s a Democrat Congressman from California’s 33rd district. Thank you so much, Congressman.

WAXMAN: You're welcome. Good to be with you.

Related links:

- Representative Waxman’s Office

- Energy and Commerce Committee

Republican Climate Hearing Agenda

Hurricane Sandy knocked out power in most of lower Manhattan, bringing the reality of climate change home for people in the Northeast. But many Republicans don’t see climate change as an urgent problem. (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Well, it's hardly a surprise, given the highly partisan nature of US politics at the moment, that Republicans have a different take on these climate hearings. David Kreutzer is the research fellow in energy, economics and climate change at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think-tank, and we called him up to ask what he thought had prompted House Republicans to call for hearings at this time.

KREUTZER: I think what they're seeing is a regulatory push to enact climate legislation as it were, or to push climate legislation, and they are worried that the science used to support some of these regulations isn’t up to snuff, and I think they would like to check into that.

CURWOOD: Now Congress hasn’t been able to pass legislation on this. What do you think of the President’s regulatory framework on climate?

KREUTZER: Well, his regulatory framework seems to be pretty much a war on coal, and if you look at the regulations, that’s pretty much what we’re getting. They’re going after coal in a variety of different ways, and pretty much no one’s building new coal plants now.

CURWOOD: David, you write a fair amount about environmental economics. Tell us what addressing climate change would mean for our economy.

KREUTZER: Well, it depends how you address it and to what level. We’re having climate change. We know that we’ve been having it for millions of years. Temperatures go up, temperatures go down, sea levels go up and down.

So I think what you want to do is say, well what do we get for the money that we spend on the different approaches to adapting or preventing climate problems? If you simply try to do it all through restricting carbon dioxide, it gets very expensive, and you don’t really get much bang for the buck. And if we were to have fully enacted, the Waxman-Markey cap and trade bill, the best high end estimate of our likely impact on world temperatures 100 years from now is about two-tenths of a degree.

David Kreutzer (photo: Heritage Foundation)

CURWOOD: What do you think is the motivation of the people who are advancing what you think are inappropriate models of climate performance?

KREUTZER: Well, if they do say there’s an amazing problem coming down then you’re more likely to hear them than if you say there’s not much of a problem. You’re going to get more money to investigate catastrophes than you are to investigate if there’s nothing much happening.

CURWOOD: So this is the Chicken Little school of getting budgets, you say?

KREUTZER: Ah, that’s a pretty good description.

CURWOOD: Now the House Committee that’s having these hearings...up until now they had refused to hold any hearings on climate change. David, what do you think this might signal in terms of a shift in their perspective on the science of climate change?

KREUTZER: Well, I think they are more confident in the science supporting the positions they’ve held, and it’s not the mindless – ‘there’s no warming, C02’s not a greenhouse gas’ - I don’t know any skeptics, serious ones, that hold that position. The question is how much warming are we having? Are we heading toward a catastrophe? It seems to be very clear we’re not, and to what extent can you moderate that temperature increase and what does it cost, or are there other approaches, other better ways, to spend money to protect ourselves from hurricane damage and tornado damage and to promote economic growth?

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand, the proposed witness list includes representatives from every major agency to talk about the climate change programs and the budgets associated with that. Some cynics have suggested that perhaps the House is looking for an opportunity to further cut agency action on climate change from the federal budget.

KREUTZER: Well, I think they would want to look and see what benefit you’re getting from it, and if you’re not getting much benefit and it’s costing a lot then maybe they would want to cut it. I mean, that’s pretty generic. You want to spend your money effectively, and just calling something a climate policy doesn’t mean actually it is one, doesn’t mean it’s an effective one, and it doesn’t mean it’s affordable.

CURWOOD: Now the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change will shortly have its latest report out which gives it 95 percent confidence that humans are having an effect. And the numbers they have show that we may well be headed on the path to catastrophe here. If Congress can’t act, and the President sees warnings that we could be headed into catastrophe, what alternative does he or she have but to use a regulatory process?

KREUTZER: Well, there’s a bait and switch in that argument you just gave. And that is there’s 95 percent confidence that humans are having an impact. I don’t know if it’s 95 percent, let’s say it’s 100 percent. The question is how much impact are they having.

CURWOOD: Well, wait a second...

KREUTZER: That’s where you don’t have this huge consensus that people keeping talking about. Yes, you can get a whole bunch of scientists to agree C02’s a greenhouse gas and we’re emitting C02. You can’t get this 93 or 97 percent or whatever to say that we headed towards seven feet of sea level rise in 100 years or something like that.

CURWOOD: Yes, I would say that the science I’ve been shown involving the IPCC is pretty firm about the range that we’ll get on the two degree [Celsius] rise that international agreements say that we’re trying to limit things to. Let’s say that the scientists who say that we’re headed to catastrophe, there’s a 10 percent chance that they’re right. Is that an appropriate risk for our civilization?

KREUTZER: Um, I don’t think it’s a 10 percent chance that it’s right.

CURWOOD: David Kreutzer is the research fellow in energy, economics and climate change at the Heritage Foundation. David, thanks so much for taking this time with me today.

KREUTZER: Thanks for giving me the chance to give my view.

Related link:

David Kreutzer at Heritage

[MUSIC: Kreutzer: George Duke “Creepin” from Face The Music (Big Piano Music 2002)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...why some fish contain more toxic mercury than others. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Horace Silver: “Rain Dance” from Serenade To A Soul Sister (Blue Note Records 1968) Happy Birthday Horace Silver (09/02/1928)]

US Reactor Safety In Light of Fukushima

Fukushima Reactors 3 & 4 after meltdown of 3 began. ( Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. The news coming out of Japan about attempts to clean up the wrecked Fukushima nuclear power station and contain the tons of radioactive water leaking into the ground and the Pacific Ocean is not reassuring.

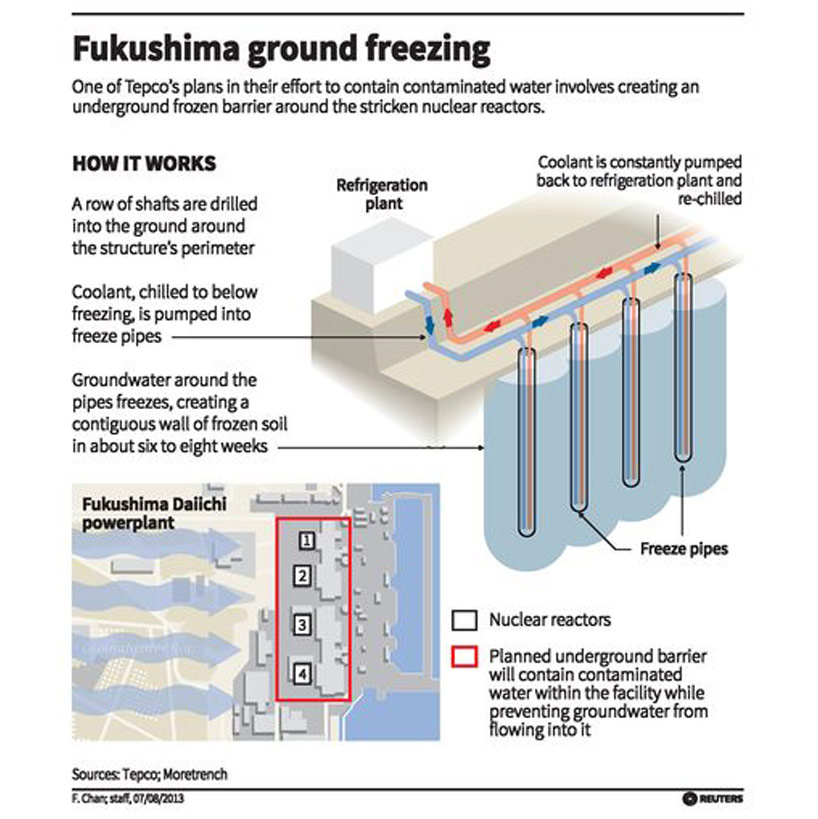

A diagram demonstrates how coolant will be used to freeze the soil in a wall around the Fukushima nuclear facility and prevent ground water from coming in contact with radioactive waste. (Tepco)

Now the Japanese Government is pledging nearly half a billion dollars to try to freeze the ground under the melted down reactors, to try to control the leaks that way. It sounds like a desperation play, so we turned to a senior scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, Edwin Lyman, to find out whether this could work, and what the condition of the plant is at the moment.

LYMAN: The situation seems to be pretty bad and it's getting worse. The plant is leaking radioactive material every day into the ocean, and right now the plant’s operator Tepco is unable to stop it.

Fukushima Prefecture is featured in red. (Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Now the Japanese government says they want to build a wall of ice around the reactor. How would that work?

LYMAN: The idea is, you would create essentially, artificial permafrost. The idea is to embed pipes about 100 feet deep in a ring around the damaged reactors and run coolant through those pipes, so essentially you’re running a refrigeration unit that would slowly freeze the soil and would turn into an impenetrable block of ice.

CURWOOD: How long would the ground need to be kept frozen? To what extent would generations in the future still be trying to keep the refrigeration running?

LYMAN: Well, that really depends on the timeline for actually cleaning up and stabilizing the site so we’re talking about potentially decades.

CURWOOD: I think people are not familiar with this icewall technology you’re talking about. How common is it? And at what scale?

LYMAN: It is a technology that has been used in other applications for a long time, particularly during mining excavation, but has not been used on a large scale to deal with a situation this delicate involving radioactive material, and not for the kind of time scale we’re talking about. So in effect it really is uncharted waters in regards to Fukushima.

CURWOOD: And by the way, where does the electrical energy come from to freeze all that soil? I understand that Japan shut down the vast majority of its nuclear power plants.

A large area around the Fukushima nuclear facility will be uninhabitable for generations.

LYMAN: Yes, the irony is they will need a significant amount of power to operate this refrigeration system, and right now Japan depends heavily on imported natural gas for a lot of its electricity.

CURWOOD: Now I know the government utility Tepco has tried some other options to contain the leak, but everything seems to come up short. This wall of ice kind of sounds like an act of desperation. What’s your take on it?

LYMAN: I think that’s a good description. There aren’t any good options in dealing with this mess. You just have to come up with a way to divert groundwater so that it does not run through the site and pick up radioactivity, and there are only a few ways you can do that, digging trenches and filling them with some sort of impermeable material. Ice is one option, but it seems to be, I would think, a slightly more unstable option because you do need to maintain active cooling for a long period of time.

CURWOOD: Now the same time that things are going on at Fukushima, Entergy Corporation has announced plans to cost the Vermont Yankee nuclear power plant next year. Why are they doing that?

LYMAN: The economics of nuclear power in the United States is very precarious right now. The price of natural gas is extremely low, primarily because of the availability of gas from fracking. And the nuclear power plants that are running today are simply unable to compete in many cases because of the ongoing operations and maintenance costs just to run nuclear power plants safely.

CURWOOD: What about the experience at Fukushima? Has the nuclear regulatory commission in the United States changed the safety rules as a result of that accident?

LYMAN: Yes, the nuclear regulatory commission has made certain changes and introduced some new requirements for reactors, especially the type of plant at Fukushima, which is the same as Vermont Yankee, a General Electric Mark 1 Boiling Water Reactor, and more changes are in the works. And even though the industry has tried very hard to limit the scope of those changes, there still is a significant price tag associated with them. And Entergy did cite the cost of post-Fukushima upgrades as one of the reasons why they’re shutting the plant down. Frankly, to have nuclear power that’s safe enough so that don’t have another Fukushima simply may not be affordable.

CURWOOD: Where in the United States are there nuclear power reactors in analogous positions to Fukushima...in other words vulnerable to earthquakes and such?

LYMAN: Well, I think in United States, the biggest threat is actually from upstream dams. There are a few dozen plants on rivers or lakes, which are vulnerable in the event of a dam failure, to being flooded in a very short period of time, as happened in Fukushima. And the nuclear regulatory commission has known about the danger of dam failures for many years, but it has been taking a very, very long time to try to resolve these issues.

CURWOOD: Where are these dams that you’re concerned about?

LYMAN: One plant which is the most vulnerable is called the Oconee in South Carolina. There are three reactors there, and the plant’s owner, Duke Energy, has been sparring with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission about how to reduce the flooding from dam failure. Still unresolved. The industry simply isn’t prepared to deal with nuclear accidents, before they happen or their aftermath, and it’s that lack of preparation, and that mindset that we don’t have to worry, it can’t happen here, that I think continues to pose danger to people all over the world.

CURWOOD: Ed Lyman is senior scientist of the Global Security Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thanks so much, Ed, for taking this time.

LYMAN: Thanks for the opportunity.

Related links:

- More about Edwin Lyman

- Huffington Post blog on risks of US reactors near waterways

- Tepco

[MUSIC: Innamorati/Various Artists “Clownie” from Transgenerational Bass Presents Transnational Dubstep (Six Degrees Records 2010)]

Pink Salmon In Trouble on the White River

The fish trap at Buckley Dam has not been updated since the 1940s. With the massive influx of pink salmon, managers can’t separate out the endangered chinook,steelhead and bulltrout from the pinks. (Resource Media)

CURWOOD: The National Academy of Sciences just released a report detailing the results of federal efforts to rebuild depleted fish stocks - and found mixed results. But in the Pacific Northwest, scientists have seen a considerable recovery of stocks of pink salmon. Just now hundreds of thousands of pink salmon are swimming back to spawn in the rivers and streams there, but it's not always a happy outcome for many fish that choose the White River east of Tacoma. Thousands of them are dying, due to an outdated dam, and the inability of federal officials to transport the salmon round the obstacle to safe spawning grounds upriver. From the public media collaborative EarthFix, Ashley Ahearn has the story.

AHEARN: If you follow the Puyallup river inland from Commencement Bay and hang a left up the White River, you will eventually come to the Buckley diversion dam. It's a small dam, only about 15 feet high, but it's very old and very dangerous for fish. Russ Ladley stands in the shallows below the dam with a haunted look in his eye. He's a fisheries biologist with the Puyallup Indian Tribe. Pink salmon carcasses litter the rocks around his feet. He nudges one with his boot.

LADLEY: This is a female, right here. Full of eggs.

AHEARN: The silty waters writhe with fish, still fighting. Some of them are visibly battered and lethargic. Others continue to heave themselves onto the lower section of the dam‚ their bodies scraping over old exposed nails.

LADLEY: But yeah, this goes on 24 hours a day, 7 days a week until the fish are just depleted of all their energy reserves, then the current and the color of the water hides the bodies and they will be scattered downstream.

Mud Mountain Dam. (Ashley Ahearn)

AHEARN: Ladley estimates that up to 200,000 fish will die here in the next month, during the height of the pink salmon run. There is no hydropower being generated at this small dam. The Army Corps traps fish here and then loads them into trucks and drives them around a much larger dam 6 miles upriver.

That dam was built in the early 1940s for flood protection, without any way for fish to get around it. The recovery of salmon in this river depends on their ability to get above these dams to spawn.

But the Buckley dam hasn't been updated since the 40s and the fish kills have gotten worse in the last decade as pink salmon have started coming up the White River by the hundreds of thousands.

Scientists aren't exactly sure why these fish are rebounding in Puget Sound, as other types of salmon suffer, but Russ Ladley says this old trap and haul facility can't handle all the pink salmon, nor can it sort out the endangered Chinook, steelhead and bull trout that also come up this river.

LADLEY: It is no longer effective. These pink runs have come out of nowhere and they've overwhelmed the system. There are more fish here now than the Corps can effectively move.

AHEARN: 12 miles upriver from where Russ Ladley was standing, a truck backs up to a long metal chute and opens its rear hatch.

[FX HATCH OPENING]

AHEARN: Out pours 1200 gallons of water‚ and about 300 pink salmon.

[THUD THUD OF FISH]

AHEARN: These fish were trapped down at the Buckley Dam. Now they're being released into the upper reaches of the White River, free to spawn anywhere from here up to the foothills of Mt. Rainier. It's a critical part of their lifecycle.

The Army Corps spends an extra 600,000 dollars moving the massive influx of pink salmon around these dams. They've added 4 more fish trucks that operate around the clock. That's allowed them to move up to 20,000 fish a day but the tribes estimate there are more than double that arriving right now.

GOETZ: We're at our capacity. If there are more we're going to do our best to move that backlog.

AHEARN: Fred Goetz is a biologist with the Army Corps of Engineers. He acknowledges that the trap and haul facility isn't up to the task of moving all the fish that get stuck below the dam.

Fully replacing the Buckley Dam would cost close to 80 million dollars. Goetz says the Corps doesn't have that kind of money right now. Instead it hopes to spend about half that amount and replace the old dam, but not improve the fish trap there.

GOETZ: We're doing everything we can right now, especially when we don't have a lot of funding and we may not see very much in the future as well.

AHEARN: The Muckleshoot and Puyallup tribes say replacing the dam isn't enough. The old fish trap also needs to be replaced. That way the tribes can focus recovery efforts on endangered Chinook and bull trout that get mixed in with the hundreds of thousands of pink salmon in the river.

Don Gerry is a member of the Muckleshoot tribe and serves on the tribal fish commission. He's standing next to the Buckley dam, where salmon are dying as they wait to be transported upriver.

GERRY: We need to take care of them, and the federal government isn't doing their part. They're the ones that caused the problems with the decline of the salmon. We're left with the burden of trying to rebuild it.

AHEARN: The Army Corps expects that it could take up to 8 years for this dam to be replaced, and right now they're not planning on building a new fish trap.

I'm Ashley Ahearn on the White River.

CURWOOD: Ashley reports for the Pacific Northwest public media collaborative, EarthFix. There are photos and video at our website LOE.org.

Related links:

-

-

- More from Earthfix

Why Fish Have Different Amounts of Mercury

Lanternfish, the deepest of the species measured, bioluminesce on their undersides for camouflage. To deeper sea predators, the lanternfish blends in with the sunlight scattering through the shallower ocean waters. (Photo: C. Anela Choy)

CURWOOD: Now eating fish can be beneficial to your health, as long as the fish you choose isn't laced with contaminants such as mercury. The body can metabolize small amounts of mercury, but too much is toxic to the brain and nervous system, and children and fetuses are most vulnerable. For years, scientists have noticed that deep sea fish contain more mercury than fish from shallower waters. Now, a paper published in Nature Geoscience explains why different fish have different amounts of mercury. Joel Blum is a professor of geochemistry at the University of Michigan, and co-author of the paper. Welcome to Living on Earth.

BLUM: Well thank you. Great to be here.

Joel Blum, geochemistry professor at the University of Michigan, studies how trace elements and toxic chemicals move from one source to the next. (Photo: Joel Blum).

CURWOOD: So, your most recent study was about the toxic mercury found in fish. What did you notice about the different fish found in your study?

BLUM: Well, prior to this particular study, a colleague of mine had noticed that the deeper the fish lived in the ocean, the higher the concentrations of mercury were in their tissues. So we wanted to understand why that was, and the study we’ve just done was focused on that problem.

Co-author Brian Popp holds up a Mahi-Mahi caught for this study. (Photo: Brian Popp).

CURWOOD: So why is it that these fish have different amounts of mercury depending on deep they swim in the ocean?

BLUM: So the key to understanding mercury is that there are several different forms of mercury in the environment, and there’s one form that is taken up into fish and is most toxic, and that is called methyl mercury. And what we found in our study is that methyl mercury is formed in the ocean, in a variety of different depths in the ocean. But when it forms near the surface of the ocean, sunlight breaks down the methyl mercury back to its common form, and therefore essentially detoxifies it. But deeper in the ocean, where there is no sunlight, this process doesn’t take place, and so the toxic form of mercury can build up, and can be incorporated into the food web and ultimately into fish.

BLUM: Where does the mercury in the fish come from? In general, most of the mercury that’s in the ocean came from the atmosphere and was deposited into the ocean in rainfall. And so the next question would be why is there mercury in the atmosphere? The main source of mercury in the atmosphere is the combustion of coal that we use to produce energy.

A fish auction in Hawaii sells local Opah, or moonfish. (Photo: C. Anela Choy).

CURWOOD: So most of the mercury in the atmosphere is not this toxic methyl mercury. How does it get that way?

BLUM: The inorganic mercury that’s in the atmosphere is processed by bacteria, which turn it into methyl mercury. One of the things we found in our study is this processing, or this methylation, can happen in the open ocean, which we didn’t previously realize.

CURWOOD: How does the mercury affect the fish?

BLUM: As far as we know, the mercury doesn’t have a direct effect on the fishes’ behavior or health. At the levels, it’s found in fish, it certainly can affect humans who eat the fish, but the fish themselves don’t seem to be affected by the mercury.

CURWOOD: And these fish that you’ve done your research on are fish we’re likely to eat, right?

Researchers used a large net to catch the nine species of fish tested for mercury in the study. The net weighs 2000 pounds dry. (Photo: Jeff Drazen).

.jpg)

Marine Technician Meghan Donohue carefully directs the launch of the net. The net consists of different bundles that can be selectively opened to catch fish at specific depths. (Photo: Jeff Drazen).

BLUM: Yes, we looked at a whole range of fish. We looked at nine different species of fish, and among those are several different types of tuna, swordfish, a number of commonly eaten fish from the Pacific Ocean.

CURWOOD: You studied fish in the Pacific. How do mercury levels in the Atlantic fish compare to that?

BLUM: Well, they’re similar. There’s a recent study that compared mercury in the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean, and it seems that mercury in the Atlantic over time is decreasing somewhat, which is believed to be the effect of reduced emissions of mercury for North America, whereas mercury in the Pacific Ocean is on the increase due to increased emissions from the Asian continent.

CURWOOD: And that would be burning of coal then?

BLUM: Exactly. That’s the main source of mercury that’s coming to the atmosphere from Asia.

CURWOOD: So by the way, Joel, from your research, which fish were the most loaded with mercury?

A typical haul from one of the nets consists of fin fish, jelly fish, pelagic eels, and crustaceans. (Photo: Jeff Drazen).

BLUM: The fish that had the highest level that we studied were swordfish. And swordfish are top predators, and they also live deep in the ocean, and that kind of double whammy gives you the highest levels, and those are fish that one really has to consider how much they eat because the exposure to mercury is really quite significant.

CURWOOD: What do you hope comes of this study, Joel?

BLUM: Well, what we’ve really done is improved our understanding of the whole cycle of mercury, of how it gets into the marine environment, how it becomes toxic and where it gets taken up in the food chain. And so by having a better understanding of this process, we hope that we can inform people about which fish should be avoided and which fish have lower levels of mercury and would be better choices for consumption.

CURWOOD: Joel Blum is a geochemistry professor at the University of Michigan who traces toxic metals through the environment. Joel, thanks for taking the time with me today.

BLUM: You're very welcome. It was a pleasure.

Related links:

- Details of the fish mercury study

- About Joel Blum

[MUSIC: Funkadelic “A Joyful Process” from America Eats It’s Young (Westbound Records 1972)]

Tough Neighbors--Coopers Hawks

Coopers Hawk (Photo: Finiky)

CURWOOD: One of the great joys of life in the American South can be getting to know and understand your neighbors really well. Commentator Pat Priest of Athens, Georgia, though, finds the way some of them behave is alternately delightful - and off-putting.

PRIEST: I caught my neighbors in our pool some weeks ago, two of them, bathing. I slipped back into the shadows of my den and pulled out my binoculars. My husband and I bought a better pair just for this reason. Spying on the neighbors is endlessly fascinating.

I don't know where they spend the winter. The parents fly in sometime in the spring to ready their home. Only when the weather warms do we see the mom and her plump babies out and about, hunched . . . and see her watching us, eagle-eyed.

She's often gorging on some kind of meat, ripping, ripping, head back pulling. I shout, "Hullo!" to them sometimes, but the mother only shrieks to her youngsters to stay back. I'm wary of them, too. When my mom visited with her tiny Chihuahua-mix, I never let the pup outside without supervision.

Through the binoculars I study one of the youngsters. It looks like he has yellow tights on. They all have the loveliest breasts – like vanilla ice cream streaked with caramel. Their toenails, their beaked noses could rip me to shreds. I see this one scratching his face. That has got to hurt!

They're big; maybe 18 inches tall. Coopers Hawks, I think. I get some of my best nature watching in while I'm brushing my teeth, standing at the window that looks out at the woods. Once I saw one of the hawks sitting on the fence, minding its own business. Suddenly a squirrel rushed at him, running along the fence top, appearing out of nowhere. The hawk exploded in flight.

Coopers Hawk (Photo: Pete)

What instinct or desperate courage propelled that squirrel?

Another time I watched as a hawk - maybe in a grudge match - raced after a squirrel, which circled round and round a tree trunk. I'd seen squirrels chase each other in tight circles and figured it was only playful - or fueled by romance. That practice paid off: the hawk couldn't turn in such spirals, and the squirrel got away. That time.

This year the hawks have moved into our blueberry patch, and we didn’t even need to cover our blueberries to keep birds out, as about 80 percent of a Cooper's Hawk's diet consists of birds. The hawks are like scarecrows that suddenly pounce.

Sometimes I see the red and dun-colored feathers of their victims. I'd like to shout up at them: can't we all be vegans here?

Thoreau wrote, ‘I love a broad margin to my life.’

Our woods are a green and leafy margin that provides astonishing sights and sustains my neighbors . . . owls, bats, salamanders, inchworms, and more. Whether they're passing through or live here year round.

I don’t see or hear the hawks much these days, a sure sign that summer is waning. I look at all the wild creatures and think: Rest a while on your journey. Or make yourself at home. I hope these woods provide shelter for many generations of your family.

CURWOOD: Pat Priest teaches nature writing and dreams up fund-raising events for nonprofits in Athens, Georgia. Thanks to Neal Priest for production assistance.

[MUSIC: Coleman Hawkins “Think Deep” from The Hawk Flies High (Riverside records 1957)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...it’s harvest time in much of the US and for some folks, when it comes to tomatoes, bigger is better. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Horace Silver: “Senor Blues” from Six Pieces Of Silver (Blue Note Records RVG Reissue 1998)]

Data Gaps For Chemical Safety

Deteriorating portion of the MIC plant, Bhopal, India, decades after the deadly gas leak. Source of ongoing contamination. (Wikipedia, 2008-06-17 original upload date)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. On April 17, a chemical fertilizer plant in the town of West, Texas, blew up. The explosion killed 15 people, wounded over 150, and prompted nationwide questions about the hazards of chemical plants, particularly those that handle fertilizers. But when a team of reporters at the Dallas Morning News tried to find out how often accidents like the one in Texas occur, they discovered that no regulators are keeping track. Daniel Lathrop is a Staff Reporter and data specialist at the Dallas Morning News.

LATHROP: Initially we had a simple question, how often do things like what happened in West happen elsewhere? What have been the warnings leading up to it? How could this have been prevented? What do we know? And so the most basic question of that was how often has this happened before? And we couldn’t find out. And we talked to agencies, and we gathered data, and we increasingly realized that no one knew.

CURWOOD: So is there any government agency at any level that’s tasked specifically with collection and analysis of data of chemical storage or processing facilities?

LATHROP: No. No, there isn’t, which seems shocking, but it’s split between OSHA, the EPA, the Department of Homeland Security, state agencies of various kinds, and often simply left in the hands of local fire marshals and local fire departments.

Noxious smoke billowing from the Magnablend chemical plant in Waxahachie, TX, prompted the evacuation of nearby neighborhoods and schools in October 2011. (Dallas Morning News)

CURWOOD: So do potential regulators of companies want to know what’s going on?

LATHROP: We had trouble answering that question. The environmental groups that we asked suggested that it’s pressure from industry, other experts that we’ve talked to have said that industry certainly has no interest in promoting this, but hasn’t necessarily opposed it either. One of the things an EPA official who’d been involved in that effort in the mid-1980s said was essentially different people come in, they lose interest in what somebody else was doing and it’s not necessarily their priority.

CURWOOD: Well, back in 1986, the Emergency Planning and Community Right to Know Act was passed in the wake of a huge chemical disaster that killed thousands of people in Bhopal, India, when a Union-Carbide plant exploded. And that legislation, as I understand it, requires companies to disclose information about dangerous chemicals that they store, and to calculate worst case scenarios so that nearby communities can plan for disaster. That law’s on the books. What’s happening with it?

LATHROP: Well, since then there’s been a lot of rollbacks. There’s been a concerted effort from a variety of sources to make that information hard to get, hard to access. There’s no real data verification or confirmation that goes on with any of what gets reported. Most of it is reported only to state agencies, and again, a state agency here in Texas told us, well, we collect it, but we don’t have the authority to do anything with it.

CURWOOD: One of the things that we found that was interesting about the Emergency Planning and Right to Know Act is that only certain chemicals are regulated under that, and the list doesn’t include fertilizer, the ammonium nitrate that blew up at the West fertilizer company.

LATHROP: Yes, in fact, the ammonium nitrate in federal law and regulation has a very special status, it’s one of a small number of chemicals that not just isn’t regulated, but has special sort of anti-regulatory status where the EPA is prevented from regulating it under some circumstances. For example, it’s illegal for federal and state and environmental agencies to regulate ammonium nitrate when it is for direct sale to the consumer, in this case, generally farmers. So ammonium nitrate fertilizer, like the kind that was mixed and sold at West, is, in fact, not required to be dealt with under EPCRA, if it is for direct sale to consumers. In the case of West, they chose to disclose it anyway. It’s not clear to us whether they actually had to.

CURWOOD: Now ammonium nitrate, of course, it’s a fertilizer, but famously it’s quite explosive. Oklahoma City bombers, for example, used it. Seems kind of amazing that there’s no record being kept of where the stuff is stored or what’s happened in terms of accidents.

LATHROP: It is amazing. We can’t understand why this particular chemical has sort of had regulatory cryptonite. There have been major disasters involving this, either deliberate terrorist attacks or major accidents that have happened - quite a few going back 70 years in the United States.

CURWOOD: In your story, you wrote, I believe you quoted Sam Mammon, he’s a nationally recognized chemical safety expert, who told you, “We can track the Gross National Product to the second and third decimal, but there’s no reliable way of tracking simple things like how many chemical accidents happen.” He recently testified on Capitol Hill. What appetite do you detect in Washington to take on this issue?

LATHROP: We’ve detected no appetite in Washington to take on this issue. It’s a kind of boring issue. It’s something as simple as knowing what has happened so that you can make intelligent decisions about it. In the mid-80s the EPA took a stab at this. They created a pilot program to track these, and that was basically not very successful and not renewed afterwards.

CURWOOD: You said this is boring, but the disaster in West, Texas, was far from boring.

LATHROP: I agree. I think it’s incredibly important. I don’t think we can make good decisions as a public. I don’t think that we can set proper regulations on companies. I don’t think that we can make any real decisions if we don’t know what it is that we’re making decisions about. The things that are not being collected as data are frequently horrifying accidents that kill people, that maim people, that destroy property, that lead to neighborhoods and cities being evacuated. But no one in Washington wants to talk about how to keep track of it.

CURWOOD: Daniel Lathrop is a Staff Reporter and Data Specialist with the Dallas Morning News. Thanks for taking the time with me today, Dan.

LATHROP: Pleasure to be here, Steve.

Related links:

- fter West disaster, News study finds U.S. chemical safety data wrong about 90 percent

- Many Texas plants lack safety inspections despite risks, data shows

- Developing a Roadmap for the Future of National Hazardous Substances Incident Surveillance, Texas A&M University, 2009

- U.S. Chemical Safety Board website

- Explosions: How They Work

[MUSIC: Club D’Elf “Sand” from Electric Moroccoland (Club D’Elf Productions 2011)]

Mortgage Lifter Tomatoes

Photo courtesy of Jeff McCormack

CURWOOD: For many gardeners, this is the best time of the year, when they get to harvest their eggplants and peppers and cabbages and above all, tomatoes, and show them off at harvest festivals and county fairs. And even for those less expert with the spade and the trowel - nothing can beat the sight and smell of vines laden with Big Boys and Romas and Sweet 100s.

The most desirable of all tomatoes are those heirloom varieties in all imaginable colors and shapes - the deep red and pink Brandywines, the dark Cherokee Purples, the Black Krims and stripey Green Zebras. Reporter Jeff Young decided to investigate the history behind one of his favorites - a tomato with an especially peculiar name - and he discovered a story behind it is as colorful as the fruit itself.

YOUNG: Where I grew up in West Virginia, old timers called them Mortgage Lifters. They’re tasty without being acidic, and the flattened, pinkish fruits get big. Really big—I’m talking a pound or two a piece. The best of them carried a longer name: Radiator Charlie’s Mortgage Lifter Tomato. I often wondered about that name. So did Jeff McCormack.

McCormack runs a seed catalog company from his home in Charlottesville, Virginia. He specializes in rare lines of heirloom plants and seeds passed down through families and friends.

MCCORMACK: You know when it’s being passed down in a family for 200 years there must be something good about it.

YOUNG: In the mid 80s McCormack got his hands on some tomato seeds and a heck of a story. It came in the form of a scratchy old tape recording of a conversation between Ed Martin of Virginia, and his grandfather, the originator of the Mortgage Lifter tomato.

[ARCHIVE TAPE: "I am sitting at 860 Lee St talking to my grandfather MC Byles and he’d get mad if anybody said it is Marshall Cletis…”]

YOUNG: Marshall Cletis Byles preferred to go by M.C. or just Charlie. The tape is tough to hear—cars, trains and at one point an ice cream truck interfere. But it rewards the careful listener. Martin tries to keep his grandad on topic—he wants to know the origin of the mortgage lifter tomato.

[ARCHIVE TAPE: “That’s a heck of a tomato. Look didn’t you tell me there

were five tomatoes that made that thing?”]

YOUNG: Byles talks about the tomato all right, but not right away. He wanders in his recollection, as 85-year-olds are wont to do. He talks about cars he’s owned, jobs he’s worked, place he’s lived—and what emerges is the story of a truly remarkable life. The grandson asks how Charlie got started with gardening. Byles tells him it was when his mother sent him to work in the cotton fields of North Carolina. He was four years old.

[BYLES: "Mother said ‘come out from under there’ I said ‘what do you want?’ She said, ‘you’re going to work.’ ‘I’m too little to work.’ ‘No you are not.’ I had to go out there and start pickin’ cotton."]

YOUNG: As a young man in the National Guard Byles took up wrestling and got so good he went on a wrestling tour of towns in Appalachia—where it’s called wrasslin’. The pay was a dollar for every minute he lasted in the ring.

[BYLES: "What you did, if he didn’t throw you in 10 minutes you’d get a dollar a minute. I never lost, but very few times."]

YOUNG: Byles learned to pilot small planes and flew airmail routes. He loved fixing planes and inventing things. He once came up with a new kind of garden tiller, but didn’t think to get a patent. He found business success as an auto mechanic in the rugged hills of Logan, West Virginia, where heavy coal and timber trucks constantly blew out radiators grinding up the steep grades.

MCCORMACK: And I think that’s where he acquired his name Radiator Charlie.

YOUNG: That’s seed saver Jeff McCormack.

MCCORMACK: Incidentally the shop was located at the foot of a large mountain where the trucks had to roll back down the mountain to his shop after the radiator blew.

YOUNG: Location, location, location. He sounds like the classic American tinkerer.

MCCORMACK: Exactly. And the beauty of it is that he did this all without formal education.

[BYLES: "Well I’ve always had a mind of doing things that nobody else couldn’t do. I never been to school a day in my life but anything I wanted to do, I done it.”]

YOUNG: Sometime in the early 40s Radiator Charlie Byles wanted to build a better tomato. You remember this is a story about a tomato, right? Well, this is how he did it.

[BYLES: "What I did I took ten plants and put them in a circle and put one in the center…"]

YOUNG: McCormack has studied this part of the tape carefully and says Byles invented an unorthodox but elegant system.

MCCORMACK: He started with 4 varieties of tomatoes and he placed a tomato called German Johnson in the center of a ring of 10 tomatoes. All these tomatoes were the largest seeds he could find in the country at the time. So he would go around the other tomatoes, collect pollen in the baby’s ear syringe, then squirt it on the flowers of the German Johnson, then he would save seed. After seven years he felt he had a stable tomato with all qualities he was looking for and once he was satisfied with that he never worked with any other tomato plants, did any other plant breeding. But he really ran with it after he developed it.

YOUNG: Ran all the way to the bank. Turns out Radiator Charlie Byles had quite a knack for marketing, and sold tomato seedlings for a buck a piece—a lot of money for a little plant in those days. He sold enough of them to pay off the mortgage on his house.

[BYLES: “I didn’t pay but $6,000 for my home and paid most of it off with tomato plants."]

YOUNG: So there you have it: Radiator Charlie’s Mortgage Lifter Tomato. McCormack says the story is more than just a good yarn. When he put it in the seed catalog it attracted curious gardeners who grew the tomato, saved the seed, and, perhaps unwittingly, helped keep the strain alive - a small victory for preserving genetic diversity at a time when most agriculture is heading toward a homogenized industrial scale. And McCormack finds something else of value in these seed stories, something a little harder to pin down.

MCCORMACK: What I’m trying to do is also sort of save the soul behind these seeds, the thin line that extends from one generation to another. And each, the people are connected with the seeds, culture and agriculture are inexorably intertwined, they’re like two sides of the same coin.

YOUNG: M.C. "Radiator Charlie" Byles died at the ripe old age of 97. At the time of his talk with his grandson he had already outlived many of his friends and family. He wondered aloud why he had lived so long.

BYLES: The lord left me here all these years for some purpose. I don’t know what it is.

MARTIN: Maybe it was that tomato.

[LAUGHS]

YOUNG: Maybe it was that tomato. And maybe that’s not so bad. For Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young in Charlottesville, Virginia.

CURWOOD: To see pictures of Radiator Charlie and his Mortgage Lifter tomato and to learn more about heirloom seeds visit our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Seed Savers Exchange

- Southern Exposure Seed Exchange – Mortgage Lifter seeds page

[MUSIC: Guy Clark “Homegrown Tomatoes” from Better Days (Warner Bros. 1983)]

CURWOOD: Next week on Living on Earth, rethinking refrigeration - using a very old method - cooling with CO2.

MAN: Technology is the key for us; we've found away to address a greenhouse gas problem using a greenhouse gas itself.

CURWOOD: A cool way to cool. Next time on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: We leave you this week with an insect orchestra. Lang Elliott and Will Hershberger recorded this Insect Concerto on a forested hillside in Land of Lakes, Kentucky. It features the raspy song of the Common True Katydid, and appears on their CD, Songs of the Insects.

[EARTH EAR SOUNDTRACK: Lang Elliot/Will Herschberger “Insect Concerto” from Songs Of The Insects (Houghton Mifflin Publishers 2007)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Poncie Rutsch, Erin Weeks, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. And congratulations to Bobby - she just got married! Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of The Nation, where you can read such environmental writers as Gwen Stevenson, Bill McKibben, Mark Hutzgard and others at TheNation.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth