July 1, 2005

Air Date: July 1, 2005

SEGMENTS

Wangari Maathai: A Watering Can, Some Seedlings, and the Greening of a Nation

/ Ingrid Lobet(48:30)

Part I: How to Persuade 100 Thousand Poor People to Plant Trees

View the page for this story

Kenya has offered the world a new model for what an environmental movement can be, one that harnesses the power of thousands of hands. Even the hands of people with little means. In 2004 the Norwegian Nobel Committee recognized this new model and its founder, Kenyan scientist and environmentalist Wangari Maathai. In the first part of this special edition of Living on Earth, Ingrid Lobet introduces us to the basic mechanics of the Green Belt tree planting movement and its Nobel Prize winning founder. (12:30)

Part II: It's More Than a Tree Planting Movement

View the page for this story

As tree planters in Kenya's central highlands have reforested their region, they've seen a change in fuel availability, the food they can cook and the vegetables they can grow. And the organization they've built to plant trees gives them a way to address other problems, including government. Green Belt has been at the center of conflict to create a more democratic Kenya. But many village members, especially women, say the most important change is in their sense of self worth. (18:00)

Part III: Soldier Planters, River-Keeping Children and Green Belt's Future

View the page for this story

Wangari Maathai's Green Belt Movement continues to forge its own path, trying to bring planting to dry regions, creating revolving loans for livestock that are paid back with seedlings instead of money, and planting trees in the national forests. Now the movement faces unprecedented demand from Kenyans inspired by their Peace Prize winner. The movement entertains possible offers from the new climate change markets as it tries to find new sources of funding to meet growing demand. (18:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

(THEME MUSIC)

CURWOOD: From NPR - this is Living on Earth.

(THEME MUSIC – UP AND UNDER)

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Today, the story of Wangari Maathai, her quest to plant trees far and wide across Kenya launched a movement and won her the Nobel Peace Prize.

MAATHAI: When God created the earth, He covered it, the way it is here, in its green color. That’s the nature of the land. It needs cloth of green. That’s where the concept of the Green Belt Movement came from. It just clothes the earth with her dress.

CURWOOD: Over the decades, Maathai’s Green Belt Movement has strengthened democracy in Kenya and empowered its women, through the planting of thousands upon thousands of seedlings.

MAATHAI: That’s how it all started. Wangari Maathai and the greening of Kenya, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

[THEME MUSIC- UP AND UNDER]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

Wangari Maathai: A Watering Can, Some Seedlings, and the Greening of a Nation

Wangari Maathai on a hillside in Kenya, 2004. (Photo: Mia McDonald, Friends of the Green Belt Movement North America)

Related link:

Friends of the Green Belt Movement North America

Part I: How to Persuade 100 Thousand Poor People to Plant Trees

Wangari Maathai on a hillside in Kenya, 2004. (Photo: Mia McDonald, Friends of the Green Belt Movement North America)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. In 2004, for the very first time in its history, the Nobel Committee awarded its prestigious Peace Prize to an environmental activist.

The winner was a scientist and an African woman. Her name: Wangari Maathai. Perhaps you've heard of the Green Belt Movement she founded to reforest the landscape of her East African nation.

In today’s program we ask two questions: Who is Wangari Maathai and why has her Green Belt Movement blossomed? Wangari Maathai says she had little idea in the beginning that teaching women to plant trees would not just demystify forestry, but would also change the lives of women and help clean up government as well. Living on Earth’s Ingrid Lobet has our story of how this very Kenyan approach to environmental activism may hold lessons for the rest of the world.

LOBET: A boundary of coffee, mango and papaya trees encircles a steep hillside in Kenya's Central Highlands. The ground is packed with seedlings, their roots wrapped in black plastic. On any morning, in 3500 nurseries like this one across central Kenya, volunteers tend their prospects. Heisal Bangui and a group of her neighbors shows me how they do it.

Eunice Nyokabi at her nursery in Ruiru, Kenya, watering a few of her 30 to 50 thousand seedlings. (Photo: Ingrid Lobet)

BANGUI: We take an empty, an empty bag, we fill with soil. We have mixed the soil with the manure and we fill and we do like that. After watering, we take seed, we put, we make a hole with finger, then we insert. We insert the seed inside here, then we water again.

LOBET: Nurseries like this one are the core of the Green Belt Movement. They begin with a call or letter to the Movement office in the capital Nairobi. Green Belt tells them: “Find a meeting room in your school or church and invite everyone.” Then a staff member goes to the meeting and helps the community choose the most gung ho or best organized among them to be leaders. People learn to collect tree seeds and how to choose a nursery plot. They prepare the ground. Then the Movement gives them the precious black polyethylene tubes for tamping in the soil, the African version of the cardboard seedling pot.

LOBET: Heisal and her friends lead me over to a hand-dug hole, about six-feet deep.

BANGUI: This is where we get water for watering. We use the can... this is the can we use.

LOBET: To get water you must step steeply down into the hole, brace your feet against its dirt sides, bend over, and fill the bucket below your feet, then swing the 20 pounds of water over your head, then up onto the ground. And you must do this for two hours at a time, twice a day until the seedlings are six inches high.

BANGUI: Oooh. Ah, this is what we do daily.

[LAUGHTER]

BANGUI: This is what we do.

[SOUND OF WATER BEING POURED]

LOBET: When the plants are one foot tall, they carry them to be planted.

BANGUI: And then we use sacks. We put about 20, and then we use our back.

LOBET: They carry the 40-or-so-pound sacks of seedlings up the hillside strapped to their foreheads.

BANGUI: You see the place is steep. So we come more than 10 times, yeah, going up and down, carrying this heavy nini. We carry 20. 20 seedlings. Just 20. And it is heavy. They are heavy because the soil, the soil is wet. Yeah, that is what we do, mmm. We feel it is our work so we can’t get tired. We can see the fruit of the work we are doing.

|

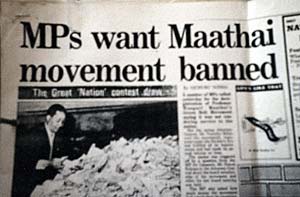

LOBET: The young trees go to members’ homes, for future firewood or shade. They go to neighbors, nearby schools, and, nowadays, to rehabilitate Kenya's ragged forests. Wherever they go, these seedlings are free, but the person receiving them must dig all the holes--a show of commitment. Green Belt members continue to tend the baby trees for three months. Then the office in Nairobi pays them an amount that's small, but crucial-- five shillings-- about seven cents a seedling. These acts of reforestation reverberate within Kenyans and their society. And the Movement has confronted the government armed with seedlings and been viewed as subversive. Once was in 1996, when Green Belt founder Wangari Maathai and her supporters, armed with seedlings, staged a series of protests at Karura National Forest, a 2600 acre wood on the northern outskirts of Nairobi. It turned out then-president Daniel Arap Moi was selling off pieces of forest to his backers. SOUTH AFRICAN NEWSWOMAN: The crowds approaching the gates of Karura are each being met by a huge police blockade. MUCHUNGI: Yeah, that day I saw death. LOBET: Lillian Muchungi is a Green Belt organizer and mother of two. And, as usual, she was with Wangari Maathai on this day to retake Karura symbolically by planting. MUCHUNGI: I was standing right next to her. That was the day I thought: maybe one day we will die over Karura. But she said there then, “on my dead body that Karura will ever be subdivided to individuals.” LOBET: A crowd of young security guards, hired to keep the protesters at bay, waited a few yards away on the other side of a fence. MUCHUNGI: When I looked at them, I knew these guys were going to beat us. They were carrying knives. They were carrying some daggers, you know, those very sharp pieces of wood and some whips, and machetes, you know. And I wanted to protect her and I wanted to talk to her to ask her not to do it and maybe go back, maybe get back there another time but she insisted, "this is the day that we are going to plant this tree. We must do it today.” LOBET: A South African news team was on hand to record the standoff. Wangari Maathai held a seedling in one hand and a wooden crucifix in the other. MAATHAI: As you can see, I am holding the power of Christ. I am quite sure that the anti-Christ will not keep us away from the forest. This is the power that the man who died on this cross did not believe in and I don't either. MUCHUNGI: And she was trying to dig a hole. That is when they all jumped over the fence. And some were on her with whips and some very sharp daggers. Ten, ten young men, yes, were on us! MUCHUNGI: I was hit with a big stone here, I remember. And for her, she was now... One of them landed on her head with one of the sharp objects and when I saw blood, I started screaming, but others were on her now with the whips, from all the sides. LOBET: Maathai's head injury required stitching; she was released from the hospital a few days later. University students later joined the protests. The names of some involved in the real estate transactions were published and forest development halted. [BIRDSONG] LOBET: Where does a movement that can change a country begin? Maathai often recalls the heavily wooded hills of Nyeri where she was born. MAATHAI: I grew up in a beautiful part of the country. Full of trees, full of food, a lot of happiness, a lot of water, a lot of firewood, a lot of building material. Everything that I am now trying to replenish, there was plenty of it when I was a child. [BIRDSONG] LOBET: Wangari's Maathai's mother also planted. She sent her daughter to school in the 1940s. In middle and high school her teachers were nuns and Maathai said she learned from their model of life in service to others. Then she traveled to Kansas to major in biology at a Catholic college, then more study in Pittsburgh and Germany and back home. MAATHAI: In Nairobi, I pursued a Ph.D in anatomy in the early 70s. It seemed as though besides being a wife and mother I was destined to be a university professor, to help produce graduates of veterinary medicine who would feed the nation and East Africa with the products from the livestock industry. [‘70s MUSIC] LOBET: It was an exciting time to be Kenyan. Independence from Britain was a decade past. A young scientist wanted to advance her people. Wangari Maathai focused on livestock. She studied the brown ear tick, collecting thousands of them in the countryside in the hope of alleviating Rhinderpest, a fatal East African cattle fever. [AFRICAN SINGING] MAATHAI: When I was collecting ticks I saw environmental degradation in my country. I noticed the animals from which I collected the ticks were thin and clearly suffering from hunger. There was little grass and other fodder . Rivers were low. This information was hitting me from all angles. LOBET: Maathai saw the signs in the countryside and heard discussions about hunger at the National Council of Women of Kenya. MAATHAI: I realized the real threat to cattle in my country was not the brown eared tick, but the deteriorating environment around me. I also recognized that not only the livestock industry, but me, my children, my students and my entire country were threatened by a deteriorating environment. Deforestation, soil loss, pollution, and non-sustainable management of the land. At one seminar, I was struck that children from the central part of Kenya where I grew up, amongst plenty, were suffering from malnutrition. LOBET: Kenyan women were seeking faster-cooking meals because firewood was getting harder to find. What the British colonists had begun--cutting timber to build the East African railway--rural women were continuing in their search for fuel. MAATHAI: I listened to the women from the rural areas, and I noticed that the issues they were raising had something to do with the land. They were asking for firewood, they need clean drinking water, they needed food, they needed income because they were poor. I immediately understood that what we really needed to address those problems is to rehabilitate the environment. I started encouraging women that we plant trees. That's how it all started. [WOMEN SINGING] LOBET: Though it wasn't clear at the time, Wangari Maathai and the National Council of Women of Kenya were inventing a playbook, an operating manual not just for planting trees but for transforming the lives of Kenyan women. But to do so they had to enter the province of men, the nation's professional foresters. They weren't always eager to share their knowledge. Maathai sought then, as she would many times, to disarm the opposition, telling them, "we’re just a bunch of women planting trees." CURWOOD: Coming up, we'll hear how the Green Belt Movement and its founder Wangari Maathai reforested whole regions of Kenya and, in the process, drew the wrath of the Kenyan government. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

Part II: It's More Than a Tree Planting MovementCURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. SINGERS: Wego-yo! Wasi no kyo! [SINGING] CURWOOD: We're hearing this hour about the Green Belt Movement founded by the Kenyan biologist, environmentalist, and Nobel Peace Prize winner, Wangari Maathai. Our story resumes in the Central Highlands of Kenya, in the district of Murang'a, where women tree planters wrote this song in Maathai’s honor. [SINGING AND CHANTING] CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s Ingrid Lobet continues our story: LOBET: Today In Murang'a, the landscape is lush and green. But the older women say back in the 1970s, it looked quite different. [WAMBUI SPEAKING SWAHILI] VOICEOVER: I can give you an example from here, right where we’re sitting. LOBET: Green Belt veteran Margaret Wambui [WAMBUI SPEAKING SWAHILI] VOICEOVER: This was bare soil, all the way over to there, bare soil! The birds would take dust baths here. There weren't any trees or even grass like you see now. The soil you see over on that hill could even have come from here, because the wind was always blowing away our soil. We even called it "the devil wind". [WAMBUI SPEAKING SWAHILI] VOICEOVER: From the moment we planted these trees we've noticed our soil doesn't blow away anymore. Plants like these that you see just multiply now because the soil is rooted here, it stays put. And with these trees we now have fodder for our cows and firewood. That is the goodness of Green Belt. We're always singing the praises of Green Belt. [WAMBUI SPEAKING SWAHILI] VOICEOVER: When I was a girl there was a lot of firewood. But later we had to go farther, to the forest to get wood, far away. We even had to go by bus, it was so far, and come back by bus, too. And since we couldn't bring back very much in the bus, we would have to go again the very next day. [WAMBUI SPEAKING SWALIHI] LOBET: On the other side of the hill in Murang'a, another veteran leader, Edith Nyoki, sits in the shade of a stand of trees, on her property. She calls it her Garden of Eden. [NYOKI SPEAKING SWAHILI] VOICEOVER: We get wood planks for building, we get them from this very farm right here. And if you talk about eating, we plant fruit, fruit trees, we can even plant bananas, right here! This close to the house! [NYOKI SPEAKING SWAHILI] VOICEOVER: Yes, it is much better than it used to be. [NYOKI SPEAKING SWAHILI]  “There was nothing in between these houses, you could see straight from one to the next. Now you can hardly see the next house!’ said Edith Nyoki. The bare spaces have been filled in with lush green vegetation. (Photo: Ingrid Lobet) |

VOICEOVER: You could see very far! It was very dry. There was nothing in between these houses, you could see straight from one to the next. Now you can hardly see the next house! LOBET: Are the trees what she feels most proud of, the biggest accomplishment of the movement in this area? [NYOKI SPEAKING SWAHILI] VOICEOVER: We came together as one, we became a group, as a group we rear our goats, we rear our cows, like these goats right here and we're very happy because we’re even getting milk from them. It's almost as good as the trees, this coming together. [NYOKI SPEAKING SWAHILI] LOBET: The women of Murang'a have another song they sing. "Switch on the light, Wangari. Now we can see, you have been our guide. We're grateful we don't rely on anyone anymore.” [SONG: HUTIA SUI-SEE] LOBET: As the Movement spread in the 1980s, like any good organizers, Green Belt workers adapted and refined their goals and methods. They had to when they came face to face with some painful realities, realities that reached inside Kenya’s society and soul. Wangari Maathai: MAATHAI: I realized part of the problems that we have in the rural areas or in the country generally is that a lot of our people are not free to think, they are not free to create, and, therefore, they become very unproductive. They may have knowledge. They may have gone to school but they are trained to be directed. They are trained to be told what to do. And that is some of the unmasking that the Green Belt Movement tries to do, is to empower people, to encourage them, to tell them it's okay to dream, it's okay to think, it's okay to change your minds, it’s okay to think on your own, it's okay to decide this is what you want to do. You don't have to wait for someone else to tell you. LOBET: But if a certain passivity is entrenched, how to move beyond it? Many Kenyans can't read, and for others, hunger is a day away. So civic education is now at the heart of Green Belt Movement work. It sounds like this: [MURITHI LEADING A CALL AND RESPONSE IN A CHURCH ROOM IN MIRICI] LOBET: When Green Belt organizers like Muriithi Kaburi visit a community, the energy between trainer and audience in a common native language--in this case Kikuyu--can be palpable, even if, as on this day, a wicked heat radiates down on the assembled through a metal church roof. [MURITHI LEADING A CALL AND RESPONSE IN A CHURCH IN KALUCHO]. KAHARE: It's like you give people analytical skills to analyze their problems, not to just sing "problems, problems," like a song. You are telling them "Analyze your problems, and you can do something about them, don't just sit!" LOBET: That's Njogu Kahare, another Green Belt staff member. Once a local Green Belt chapter has begun planting trees, organizers urge members to examine their community problems one by one. KAHARE: All their problems they have in the world. So they list them. Sometimes they go to about 400, 500 and then you tell them “okay, are these the problems we have?” Yes. Let's see where they come from. And that is usually a very sensitive time when people are careful they are not incriminating themselves as the cause of the problem. LOBET: Often, one problem the community identifies is corrupt local government. KAHARE: So they see like "Oohhh...so a government can be bad without us knowing.” And also they start seeing themselves as a cause of many of the problems. LOBET: For example, water may become scarce because someone illegally diverts the flow, so community members challenge each other. KAHARE: Why do you do that? Why are you selfish? Now that is a root cause. You are selfish, you don't consider your neighbors, or the water is not being distributed properly. Or the chief favors you or the people in charge of that water favors you. And, therefore, the solutions could be, "now we need to make regulations that do not favor some people." Then they decide, “now we want to go into fair solutions." LOBET: The community looks to solutions to food, water, and wood shortages that are within its power to address. It may decide to conserve water together, or to remove water-hogging trees from a nearby stream. It may insist on greater accountability from local officials. For the first 12 years of its existence, the Green Belt Movement worked this way, focusing on local concerns in largely rural areas. But in the late 1980s, that began to change when Wangari Maathai started connecting more dots, this time between Kenya's degrading land and its political leaders. As the movement broadened, it became more threatening. MAATHAI: In the beginning I was intrigued because it’s such a benign activity. It's development, exactly what every leader speaks about and so I thought that we would be celebrated and we would be supported by the system. But what I did not realize then is that in many situations, leaders, especially leaders in undemocratic countries, have not been keen to inform their people to empower their people to help them solve their problems. They almost want them to remain needy, to remain poor, to remain dis-empowered so that they can look up to them, almost like gods and adore them and worship them and hope that they will solve their problems. Now, I couldn't stand that. LOBET: A crucial moment in the evolution of the Green Belt Movement came in 1989 when the Kenyan government brokered a deal with media mogul Robert Maxwell to build a 60-story building and a four story statue of President Daniel Arap Moi in Nairobi's Uhuru Park. MAATHAI: Here is a public park, the only huge public park, it is a beehive over the weekends, especially because that is where most people from low income areas escape with their families. And the ruling party at a time when it felt very, very powerful, like nobody could touch it, it decided to build this tower and take over the park. LOBET: Maathai said she couldn't condone the project and call herself an environmentalist. MAATHAI: Every city needs green spaces. Every city needs trees. Every city needs a space where people can rest without being asked questions and without being perceived as if they are intruding. Because they, too, need space. Space is a human right, you need space. And so I campaigned to have that space protected. LOBET: Wangari Maathia's outspokenness drew immediate fire.

|