How Systemic Racism Exposes Black Americans to Pollution and Extreme Heat

Published: June 24, 2020

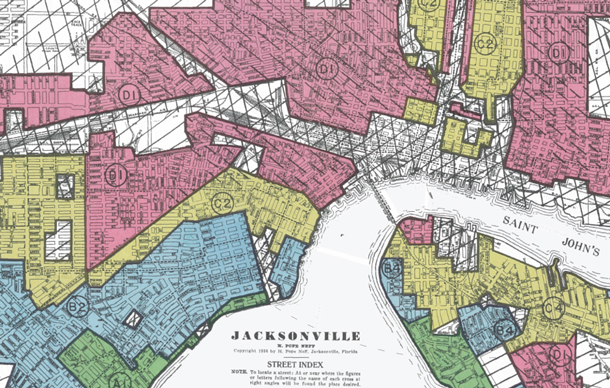

Jacksonville, Florida has a long history of segregation. (Photo: Digital Scholarship Lab)

(stream/download) as an MP3 file

Systemic racism has set Black Americans up for far greater exposure to pollution, and extreme heat brought by climate change. Both environmental concerns have been primarily caused and exacerbated by white Americans, yet it’s Black communities that bear the brunt of the harm.

Also, some stereotypes about who can be “outdoorsy” can leave people of color out. So environmental educator CJ Goulding actively and creatively works to encourage young people of color to feel that they belong in the outdoors, too -- with an assist from his Air Jordan "Bred 11" sneakers.

CURWOOD: Hi, I’m Steve Curwood and today on the Living on Earth Podcast we continue our celebration of Juneteenth, a holiday that commemorates the end of slavery in the United States.

We’ll hear about a century- old US government policy of redlining that still negatively impacts the health of communities of color today.

Also we’ll hear from a young man who is bridging the cultural divide for African American youths in the great outdoors.

But first, your support helps make it possible to bring you this podcast, so please contribute what you can.

Five dollars or more makes a difference.

You can donate right now at LOE.org and thanks!

[THEME]

CURWOOD: In the 1930s, while the world was digging out of the Great Depression, the US government drew up maps of more than 200 cities and gave grades to individual neighborhoods based on perceived suitability for homebuyers to obtain a bank loan. A-grade areas were outlined in green. They were largely suburban and white. D grade neighborhoods were outlined in red. Those tended to be in city centers and black and brown. Despite similar household incomes, home age, and other factors minority areas were more likely to be inside a red line than white ones, making it much tougher for people of color to get home loans. Nearly 100 years later the legacy of redlining persists in many ways, including increased risks from heat waves linked to climate change. Writing in the journal Climate, researchers found that during heat waves redlined neighborhoods can be as much 10 degrees hotter than other districts in the same city. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb spoke with Vivek Shandas, a lead author of the study and a professor at Portland State University.

SHANDAS: What we wanted to look at is just one climate induced stressor that we know is going to increase in frequency, magnitude and duration over the coming decades and that's urban heat. Urban heat kills more people than all other natural disasters combined in the U.S. and it particularly is a very selective killer in that the people who have died have been historically underserved communities, historically, black communities. And so we wanted to see was that policy that was fundamentally based on race and social class was that playing out to affect the communities today in terms of who's exposed to those intense heat waves at a much higher magnitude than others. And what we found was that pretty much across the country in the hundred and eight cities, we looked at those areas that were hotter, were those redlined neighborhoods.

BASCOMB: And to be clear, I mean, this is the same city we're talking about. So you're sitting in Portland, Oregon, which I believe was the city with the highest discrepancy of temperature in these redlined areas versus non-redlined areas. But why is that? I mean, why within the same city are you seeing such a dramatic temperature difference?

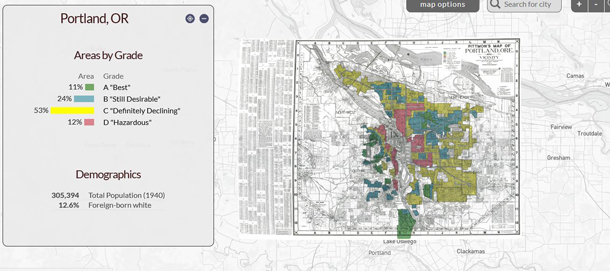

Only 11% of Portland, Oregon was considered desirable for mortgage loans between 1930 and 1940. (Photo: Digital Scholarship Lab)

SHANDAS: The temperature differences are largely a factor of differences in the physical environment. So what is in those neighborhoods now that where formerly redlined. And what we see consistently is that those neighborhoods are often either right on top of or adjacent to industrial areas. Those areas are often where the biggest freeways or highways were put in, in the 1950s. We see those areas as often having a lot fewer trees and a lot more impervious surface or that kind of concrete or asphalt that really absorbs heat over time. And so this is a phenomenon that is consistent across these cities we looked at and these historically, redlined areas have the built environment that absorbs the sun's radiation and amplifies temperatures a lot more. And as you were saying Portland, Oregon is top of the list though, Denver, Minneapolis, Columbus, Jacksonville, Philadelphia, Louisville, Baltimore. They're all in that top range of cities as well.

BASCOMB: Well, what kind of effects do you see in communities that are hotter than others? I'm thinking of even crime. I mean, I know I get cranky when it gets hot out. And we routinely see spikes in crime rates in cities, particularly when it gets really hot. Do you think that any of that can go back to this policy?

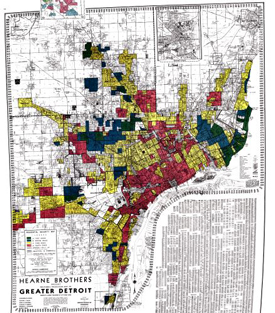

Map of redlined areas in Detroit from 1940: 6% were considered desirable (marked in green), 14% was considered still desirable (marked in blue), 51% were considered declining areas (yellow), 28% were considered hazardous (pink). (Photo: Digital Scholarship Lab)

SHANDAS: Yeah. So we've seen that people's behavior changes when it gets hotter. We've seen for example, more use of energy, we've seen greater hospitalizations, we've seen more issues of road rage and violence that happen when things get hotter in cities. And what that really comes down to is our mental health ability to cope as well as our physiological ability to cope and health impacts from increased heat as well. So we can talk about children that are exposed to heat. We've seen studies come out about how children at school are not able to focus are not able to actually do well and learn as a result of hotter classrooms or hotter environments. And so that can have a long-term effect on an ability to actually complete school. And that leads to a whole series of outcomes as well. We see this playing out in terms of our financial health; people are running their air conditioner much harder if they have access to air conditioning and have financial resources to run it. So that's money that's going away from other things like food or education or health that can be some of the basic needs for a community. And then of course, we have older adults, particularly those that have pre existing health conditions like asthma or any kind of heart condition. We've seen more recent work that's been done on stroke, brain health, in terms of heat, and that can have profound effects as well. Working with some folks at UCLA Medical School to try to better assess some of those impacts and there's no shortage of heat and and health related impacts that are occurring.

BASCOMB: We had a story on the show recently, in which we talked a bit about the dramatic difference between white and African American babies and infant mortality rates. And the statistic that really struck me is that a black woman with an advanced degree is more likely to lose her baby than a white woman with an eighth grade education. So it's not about affluence. It's not about, you know, education. To what degree is it possible that living in hotter communities is putting a physical stress on pregnant African American moms and resulting in higher infant mortality rates for them?

SHANDAS: Right. Fascinating question about the relationship between race, health and climate and a lot of the study really has some potential directions. While we don't study that in this work right here, I will say that with redlining, we find that the communities living in historically redlined areas are still communities of color are still immigrant communities are still indigenous communities and, in part what that suggests is that if you have communities of color, like a black woman living in a formerly redlined area, what you're going to see is temperatures that are sometimes five eight, ten, twelve and we've even documented air temperatures of 20 degrees hotter in particular parts of a city. So if you're talking about a 90 degree day for one part of the city, another part of the city could see 110 degree day. And once you cross that, around 98.6, about 37 Celsius degree our body is trying to cool down so our body uses sweat to be able to cool itself down. And I'm not a medical doctor though in collaboration with them, I've learned that this sweating process really helps us cool down though if the ambient temperature is hotter than 98.6 and if the humidity levels are high, we could reach this threshold called wet bulb temperatures, that's W-E-T B-U-L-B temperatures which are a point at which our body is unable to kind of cope and cool down. And so that stress that the body faces goes right into the womb that an unborn child is in and that's a level of stress that's part of that pregnant mother and that then affects the child. What we've seen in a project we're working on with five states and cities and in five states where we're looking at birth outcomes in relation to heat and air quality, we've actually seen that the smallest babies have some of the biggest effects. So these are preterm births have some of the biggest effects from the mother being exposed to extreme heat and poor air quality. So what that means is that a child being born very small actually ends up being born even smaller as a result of this exposure. And the smaller the baby gets, the more that baby has to really struggle in order to be able to live and it leads to as we've learned from the field of epigenetics, long term consequences on the health and well being of that person. The effects of redlining then can really play out in terms of what the environmental conditions are that a person, let's say, in this case, a black woman is exposed to, and that can lead to long term consequences on their ability to manage their own as well as their children's health.

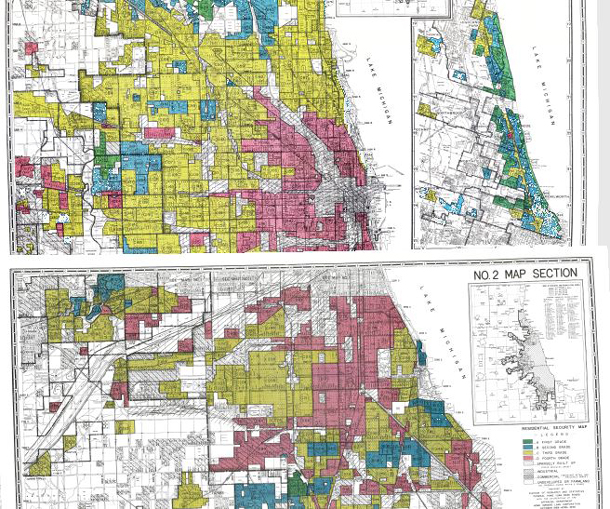

This is a map of the different levels of redlined areas in Chicago. The green areas represent desirable areas (A areas), the blue areas are still considered good but not a “hotspot” (B areas), the yellow C areas are considered declining areas, and the pink D areas are considered hazardous. (Photo: Digital Scholarship Lab)

BASCOMB: Well, it's just, it's just shocking, really how, a racist policy from almost a century ago, is persisting in so many different ways and has such long term health impacts on people that had nothing to do with that back then.

SHANDAS: Right, right. And you know, in public health, it's a very common phrase now to be talking about your zip code is more important than your genetic code. And I've heard that said by a lot of very impassioned and very committed public health staff and various agencies and community health workers, etc. And what occurs to me is that the fact that your zip code is so important for your health and well being has a lot to do with how we're going about planning our places and planning our cities. And that's really what a lot of this work kind of comes back to is, how did this policy really underscore the racial underpinnings of the country.

BASCOMB: So for somebody that's listening right now and nodding their heads in yeah, you know what it is hotter where I live, then where I work. Maybe I'm living in one of these communities that's suffering from these racist practices, what can you say to those people?

Vivek Shandas is a professor of climate adaptation at Portland State University and co-author in this study. (Photo: Vivek Shandas)

SHANDAS: Part of my job is to study cities. And I've heard a lot about people really pointing and blaming and saying, you know, I wish people in that neighborhood would take better care of their place, or I wish they would be more engaged, or I wish they would be doing things differently. And there's a lot of this, that I hear from communities that I talked to about blaming communities of being kind of, quote, sketchy or being, quote, not really worth visiting. And these are things that really hit me pretty hard, because I see through studies like the one we did, that this was a very systematic process that actually is no fault of the people that actually live there. And I guess that's really kind of at the core of what I'm hoping that this study will help reveal is that these are kind of underlying challenges that have been there and a long time. And our work then in front of us is to be engaged with the planning that's happening in our backyard with the planning that's happening all around us and to be kind of really mindful about the fact that the decisions made today could have repercussions twenty, fifty, one hundred years later, and to kind of go into this planning process thoughtfully and with recognition that these historical practices are things we have to undo and things we have to center in our current work, climate or otherwise.

CURWOOD: Portland State University professor Vivek Shandas, speaking with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

[MUSIC]

Emissions rising from working factories. (Photo: Unsplash, Desmond Simon)

CURWOOD: Dirty air is common in the US and studies show that African American and LatinX communities are disproportionately affected, especially by particulate pollution, which has been linked to high corona virus death rates among people of color. And a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science documents the racial gap between who’s responsible for air pollution and who breathes it. Here to tell us more is Christopher Tessum, a research scientist at the University of Washington, and he joins us from Seattle. Welcome to Living on Earth!

TESSUM: Hello. It's great to be here.

CURWOOD: So talk to me, what kind of air pollution are we talking about? And why is it dangerous to public health?

TESSUM: In our study, we looked at fine particulate matter, or PM2.5. These are particles that are basically so small that you can't even see them. When there's a lot of PM2.5 pollution in the air, it will show up as kind of a haze. But otherwise, you can't see it at all. These particles are so small, they go all the way down into your lungs and get stuck in the very bottom. And then they cause inflammation, which can lead to problems with your heart problems, with your lungs, and eventually it can contribute to death.

CURWOOD: How important is the risk of air pollution for environmental health?

TESSUM: Ambient exposure, to PM2.5, just fine particulate matter is the largest environmental cause of pollution. Ambient air pollution causes about 4% of total deaths United States, which is more than three times the number caused by motor vehicle crashes.

CURWOOD: Your research added some statistical certainty that racial and ethnic minorities are acutely vulnerable to air pollution because of where they live. There's also an interesting element that you put in here, which is to look at who's responsible for those pollutants that are inhaled disproportionately by blacks and Hispanics, what made you consider the exposure here for this, and the responsibility by blacks and Hispanics, and what was your measurement for that responsibility?

TESSUM: One way of thinking about it is that there's these two kind of problems or issues in society that, you know, people spend a lot of time thinking about, talking about. One is inequity in income. And then there's kind of inequity, racial ethnic inequity and exposure to environmental burdens. So what we're trying to do is trying to look for a way to look at these two problems together, because they're really related. When you have somebody operating an electricity generator, they're not just operating it for fun, you know, and they're not just sending the pollution out of it for fun, they're doing that to meet an economic demand for electricity. We try to connect, you know, who's demanding products and services with who’s emitting the pollution and who's exposed to that pollution. And so in order to do that, we came up with a metric called pollution inequity, which basically is kind of the percent difference in between the amount of pollution and the amount of exposure to pollution that people are causing, through their activities, their daily activities, their consumption of goods and services, as we call it. So the percent difference in between that, and the amount of pollution that those people are being exposed to.

CURWOOD: So what exactly were your results; give me some numbers here, compare the responsibility versus the burden for pollution among blacks, Hispanics, and then whites.

TESSUM: So we find that blacks and Hispanics are bearing kind of on average, we call a pollution burden, which is that they're exposed to more pollution than they're causing. So we find that black people are exposed to about 56% more pollution than they cause. And Hispanic people are exposed to about 63% more pollution than they cause. Conversely, we find that white people and other races on average are exposed to about 70% less pollution than they cause.

CURWOOD: So 17% less pollution than generated by their own consumption, you're saying?

TESSUM: Yeah.

The “haze” that Dr. Tessum was referring to. (Photo: Unsplash, Anz Designs)

CURWOOD: Now, from your findings, what are the overall driving factors for the air pollution problems that create these particles? And how did you measure the pollution for the folks who are in your study?

TESSUM: One of the kind of tricky parts of all this is that there's not any kind of one or a couple of different things that are causing all this air pollution, it's really a lot of different things. So historically, things like coal power plants, and heavy duty trucks and light duty cars were kind of the, maybe the three dominating factors. But over time, there's been a lot of regulation in those sectors for the power plants and the cars and the trucks, so that now, you know, the pollution is less from those; hasn't necessarily been decreasing as much for some other sectors -- in agriculture, is a more important one over time; industrial sources, things like that.

CURWOOD: So many sources of air pollution have been decreasing along the years thanks to regulation, but the inequity of exposure seems to have remained the same. So why are blacks and Hispanics contributing less to pollution but still being affected more do you think?

TESSUM: What we saw in the study was that the amount of pollution per dollar spent was getting less over time. But the thing is that black and Hispanic people are still living in places that had higher pollution levels, and white people and other races are still spending more money on average. So the underlying factors that were contributing to the inequity are staying the same, it's just that kind of pollution intensity of the economic activity has decreased over time.

CURWOOD: So when you look at an urban area, what do you see in terms of this racial disparity in terms of exposure to pollution?

TESSUM: There's kind of this long history of why people live in certain neighborhoods in the US, you know, and why certain racial ethnic groups tend to live in certain neighborhoods that may be nearer to highways, things like that, within a certain city. And different racial ethnic groups tend to live in different neighborhoods. It turns out that the neighborhoods that black and Hispanic people live in tend to have higher concentrations of PM2.5.

CURWOOD: So what's next for you for research?

TESSUM: Yeah, so there are a couple of things that we kind of ran into while we were doing this study that we would be interested in exploring a little bit more. One is looking at how this type of story plays out on a global scale, kind of looking at how maybe pollution in one country is induced by consumption in another country. And another thing that we're interested in is that this kind of pollution inequity metric that we've introduced here could really be used to study all kinds of different things, you know, things like inequities in water pollution, climate change, things like that.

CURWOOD: Christopher Tessum is a research scientist at the University of Washington and lead author of the study we've been discussing. Christopher, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

TESSUM: Thank you. It was great to be here.

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: To get the stories behind the stories on Living on Earth as well as special updates please sign up for the Living on Earth newsletter.

Every week you’ll find out about upcoming events and get a look at show highlights, and exclusive content.

Just navigate to the Living on Earth website loe.org and click on the newsletter link at the top of the page.

That’s loe.org.

[MUSIC]

CJ Goulding has only ever owned one pair of Air Jordans – a status symbol to some African-Americans -- but he’s not too concerned with keeping them pristine. (Photo: Cherish, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: A lot of backpackers wear special hiking boots when they are out on the trail, but not C.J. Goulding. CJ is a Program Manager for the Children and Nature network and when he leads young folks out for a hike C J himself wears basketball sneakers named after Michael Jordan. Here’s an excerpt from his blog on why.

GOULDING: I am an African American natural leader. That phrase is not an oxymoron but it's also not something that you normally see in the environmental world. In the few years that I've been involved in environmental education and connecting people with outdoor spaces, there have been numerous occasions where I'm the only person of color in the program, or the only African American leader. Growing up, there was no one from my neighborhood traveling, hiking, canoeing, or spending time outdoors unless it was a part of a regimented program.

But do not misunderstand the meaning behind that statement. Do not miss my point. I write neither to complain that the outdoor world is an elitist one, nor to lament the disconnect between the world I grew up in and the natural world where I now lay roots. I write to celebrate the amazing opportunity available for me and others like myself to be a bridge between the two worlds.

On my feet as I write our Jordan Bred 11s the only pair of Michael Jordan sneakers I've ever owned in my life. His sneakers are a status symbol in the neighborhood I grew up in, a memento of importance and significance. Unfortunately for some people, they hold higher value than food, books rent, and in some extreme cases, even the life and well being of another individual.

So it makes sense that while facilitating an outdoor youth summit at Harpers Ferry National Park in Virginia, an African American teenage boy stopped me to ask why I was wearing these Bred 11s outdoors. I laughed. I asked him if he had seen anyone who would wear Jordans exploring the outdoors like we were. He said no. Right there, the disconnect between the two circles was evident. And as we looked around, we could see that even there at that event we were in the minority.

I've heard the rallying cry echo, through the trees affirming that the outdoors are for people of all creeds, countries and colors.

My Jordans are now falling apart, worn from adventures in places like the Grand Tetons and the Grand Canyon. Hiking through the topography of Los Angeles and Arctic Village. This goes directly against how people quote unquote should wear them and what people quote unquote should wear outdoors. But I wear them wherever I go to remind me of the fact that though there are two worlds, I am a bridge. And I'm constantly reassured of its validity whenever I see another young leader follow the footprints of my Bred 11s into the woods.

CJ Goulding leads participants from Los Angeles and Alaska in the Fresh Tracks: Leadership Program. Fresh Tracks is a cultural exchange program that builds participant skill/knowledge in cultural competence, civic engagement, and hometown stewardship. (Photo: Tony Teske)

CURWOOD: So CJ, what was the outdoors experience that hooked you?

GOULDING: Growing up as a kid I was a wanderer and so I'd just explore the neighborhood, the trees, any forested areas, my grandmother's backyard, spending a lot of time working in her garden, and planting things and flowers and vegetables and things like that. So that's a key component of my environmental ethos.

CURWOOD: CJ, what do you think it is that keeps Black people away from nature here in the United States?

GOULDING: I think white supremacy has existed to amplify the disconnect that we have had with nature. A lot of times, history of Black people and African Americans is told starting at slavery, and that's not true. Before that, way before that we had a connection to the land, we had a connection to each other and communities. And so oftentimes, that story gets lost. And it's on purpose because a grounding and a connection in nature, amplifies and completes us and strengthens our culture. So that disconnect shows up through the way that communities of color and black people live inside inner cities with not easy access to nature, that shows up in the way that our education doesn't include that kind of knowledge. That shows up in the way that white folks have taken over some of these industries connected to the outdoors and made them an experience that requires a lot of time and a lot of money. So that connection is always with us. But I think white supremacy showed up in a way that wants to separate us from these life giving qualities.

CJ Goulding has been involved in REI’s #OptOutside campaign, which is aimed at connecting people to nature and reducing waste across the outdoor industry. (Photo: Tony Teske, REI)

CURWOOD: Tell me how do you think the the Jordans Bred 11 helped to connect with folks.

GOULDING: I call it my stepping stone theory. And for me the idea of connecting people to nature or connecting people to anything unfamiliar sometimes it's like a river that's or a creek that's running by and you can't jump it immediately. You're not comfortable enough to make that large leap. And so the Jordans helped me to be that stepping stone in the middle where I'm able to build a connection with someone and help them feel comfortable stepping into the middle because they understand that I'm there. They connect to me because I'm showing up as myself because they understand that I know who they are and where they come from. And then they feel more comfortable stepping into that unknown whether it's nature or anything else in terms of development and exposure that they're looking for.

CURWOOD: So, to what extent did you get pushback or question or even ridicule from white people who saw your show up in what they see is anachronistically his tennis shoes?

GOULDING: I think sometimes it shows up as 'hey, you're not wearing the right shoes' because they think they know the correct shoes to wear outside or outdoors and understanding that the outdoors can get to gear centric and you really don't need right shoes. You don't need $120, $200 boots to go outside. All you need other sneakers that are on your feet.

CJ Goulding is lead organizer at the Natural Leaders Network based in Seattle, Washington. (Photo: Tony Teske)

CURWOOD: Those Jordans aren't cheap though.

GOULDING: Well mine were. I got those for $4.95 at a thrift store in Alabama, so I would definitely consider that inexpensive.

CURWOOD: So after they said those aren't the right shoes, what did you say to them?

GOULDING: I don't care. [LAUGH] I mean, I realized that I had something to teach them as much as they had to teach me. Understanding that there are some cases where I need special gear and equipment and then understanding that there are some cases where it's just marketing. And I knew that my primary purpose was one to stay safe and I was doing that but ultimately to connect with the young adults I was working with.

CURWOOD: CJ Golding is a program manager for the children and Nature Network. CJ, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

GOULDING: Thanks for having me.

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Anne Flaherty, Don Lyman, Mark Seth Lender, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Kori Suzuki, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us please, on our Facebook page- Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening! And Happy Juneteenth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Links

Click here for a virtual map of redlined zones across the United States

NPR | "Study Finds Racial Gap Between Who Causes Air Pollution and Who Breathes It"

CJ Goulding's essay is featured in the book, “Coming of Age at the End of Nature”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth