This Week's Show

Air Date: February 13, 2026

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

US Losing Economic and Energy Edge to China

View the page for this story

The ongoing efforts of the Trump Administration to walk back climate policy and clean energy development may be handing over the health of the US economy to our chief economic rival, China. Veteran BBC journalist Isabel Hilton, the founder of Dialogue Earth, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss how China is outpacing US economic growth by supplying the world with clean technologies. (20:09)

Wind Power Headwinds

/ Dan GearinoView the page for this story

Onshore wind in the US is hitting a cliff, even in the most wind-powered state, Iowa, which generates about 2/3 of its electricity from wind. Dan Gearino, clean energy reporter for Inside Climate News talks with Host Jenni Doering about how a combination of local opposition, anti-wind rhetoric and tax credit phaseouts has led to a steep decline in new wind projects. (12:13)

Remembering Mike McElroy

View the page for this story

Harvard atmospheric science Professor Michael B. McElroy, a long-time board member of the World Media Foundation (which produces Living on Earth), passed away in January 2026. Host Steve Curwood offers a brief tribute to Mike’s groundbreaking contributions to research and education. (01:11)

Daisy Rewilds

/ Margaret McNamaraView the page for this story

The young hero of children’s book Daisy Rewilds not only likes nature, but she also wants to become nature. Daisy refuses to take baths and reverts the manicured lawn of her family home back into the wild, all with a bit of hilarity. Weeds and worms show her family and neighbors the true beauty in nature, chaotic as it can be. Daisy Rewilds author Margaret McNamara joins Host Steve Curwood to share how the concept of rewilding or allowing outdoor spaces to revert to more natural states, inspired this whimsical tale. (10:30)

BirdNote®: Common Yellowthroat

/ Ariana RemmelView the page for this story

Common Yellowthroats, one of the most abundant warblers in North America, thrive in places that pickier warblers pass over. BirdNote®’s Ariana Remmel reports that they’re easy to find in urban areas, marshes, overgrown fields and more. (02:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

260213 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Dan Gearino, Isabel Hilton, Margaret McNamara

REPORTERS: Ariana Remmel

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

China is now the dominant force in the clean energy future, leaving the US in the dust.

HILTON: Wind energy, solar. There's pretty much everything that you can think of that the 21st century is going to need. And China decided that it was going to be the world's dominant purveyor of those goods and technologies, and it bet the economy on those with great success.

CURWOOD: Also, the fable of a girl who not only likes nature but wants to become nature.

MCNAMARA: Daisy is a kid who goes to school like any other kid, but her passion, her heart, is all in the outdoors, and her particular area of the outdoors is not the mountains and the deserts, but it's her own environment.

CURWOOD: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

US Losing Economic and Energy Edge to China

Wind power plants in Xinjiang, China. China is a global leader in renewable energy. (Photo: Chris Lim, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The Trump Administration is moving to have the Environmental Protection Agency revoke its 2009 finding that global warming gases present a hazard to public health.

The so-called “endangerment finding” came after the US Supreme Court ruled in 2007 that states could sue the EPA over potential damages to their territories from climate disruption.

CURWOOD: Carrie Jenks is Executive Director of the Environmental & Energy Law Program at Harvard Law School.

JENKS: The endangerment finding is the science-based determination that greenhouse gasses endanger public health and welfare. It underpins EPA’s greenhouse gas regulations under the Clean Air Act, including the car and truck emissions standards, power plant regulations and limits on oil and gas facilities.

CURWOOD: And for more than 20 years that finding has vexed the fossil fuel industry, the major source of emissions, with constraints that have come close to putting the US coal industry out of business.

DOERING: But President Trump declares climate change is a hoax, despite overwhelming scientific consensus that emissions are pushing us deeper into the climate emergency. So, he is having the EPA take steps to get rid of the endangerment finding and thereby unleash the fossil fuel industry to sell perhaps trillions of dollars’ worth of natural gas, coal and oil.

CURWOOD: But they may not fully cash in, as the move could prove to be performative. Parties such as the twelve states that won the original Supreme court decision could sue to stall this attempt to revoke endangerment. Again, Harvard Law's Carrie Jenks.

JENKS: So we're going to be watching to see how courts respond to it, and how did EPA justify it, and I suspect that there will be legal risks that are quickly identified, and then it's going to be important to have those raised to the courts.

DOERING: So the repeal may not go into effect until Trump is out of office, when voters may well demand a return to federal climate action. This and other efforts of the current White House to walk back climate policy and clean energy development not only pose huge obstacles to addressing the climate emergency, but they may also be handing over the health of the US economy to our chief economic rival, China.

A coal power plant in Hailar, in the Inner Mongolia region of China. China continues to build coal power plants, arguing that it will use the plants as backup energy sources while prioritizing renewables. (Photo: Herry Lawford, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: As the US fully withdrew from the UN climate negotiations in the fall of 2025, China stepped forward with an absolute emissions reduction target of at least 7 % by 2035. And while the US is the world’s largest historic emitter of greenhouse gases, China is the largest present-day emitter.

DOERING: With the US now gone from the negotiating table, China is effectively in charge of the terms of international climate agreements. And since energy drives so much of modern commerce, China is already seizing the moment to develop its economy by supplying the world with the clean technologies of the future, as the US lags behind.

CURWOOD: Analysis by Carbon Brief already shows that in 2025 solar power, electric vehicles and other clean-energy technologies powered more than a third of China’s GDP growth at the same time the US economy had lower growth and higher inflation.

Joining us now to discuss how the US is losing economic and geopolitical power as China races ahead, is veteran BBC journalist Isabel Hilton, the founder of Dialogue Earth, which started as China Dialogue. Isabel, welcome back to Living on Earth!

HILTON: Well, thank you very much Steve, lovely to be with you.

CURWOOD: Now, what is China's political and economic position in the world today, given the US has abandoned the international negotiations and declaring an end of federal support for climate mitigation and adaptation?

HILTON: China's position in terms of climate negotiations, I guess it's stronger than it ever was. China remains a very big emitter, but it's also the world's second largest economy. It's, you know, the largest trading partner of dozens of countries around the world, and it's now the biggest supplier of low carbon goods and everything you need for the energy transition. It has a virtual monopoly position on a lot of those technologies, and it is the biggest installer of clean energy by far in the world. It installed last year, half of all the clean energy installations globally. So it's a real leader, and it remains committed to climate negotiations. There's no climate denial problem in China. There is an issue around responsibility, how fast China is going to move, when it's going to peak, and how fast it will draw down its own emissions but in terms of the process, it's a very big and central player these days.

CURWOOD: So how successful is China now in making its transition to renewables in its economy? I mean, I understand they're still building coal plants there, huh?

Solar power water heaters are very popular among middle sized cities in China. The photo shows a new neighborhood in Tieshan, a district of the prefectural city Huangshi in Hubei province. As is common in Hubei, the buildings feature solar water heaters. (Photo: Vmenkov, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 3.0)

HILTON: They are building coal plants, and there are a number of reasons for that. As we came out of the pandemic, there were two successive years in which, for different reasons, there were widespread power cuts in China, just as they were trying to get the economy off the ground. Now, if you're a provincial governor in China, you have targets to meet, you have an economy to grow, and losing power is not helpful, so you essentially want to have your form of energy security. So whilst we've seen a huge growth in electrification in China and a surge in electricity demand which has substantially been met by renewables, we still have the anxiety of what happens if there is a drought and there's no more hydropower? What happens if, for whatever reason, we lose supplies of gas and oil? The thing that China has in super abundance is coal. So it's not helpful for climate. They are very, efficient plants, and they are now saying that they're using them largely for the capacity market, which is slightly unconvincing, but that means that they're not going to have the same old system where they're committed to buy X amount of energy per year from the coal plants, which meant that they got priority access to the grid. What they're now saying about coal plants is that they will prioritize renewable energy, and they'll use the coal plants for backup when they need them. So that's the story. I'm not entirely convinced, but you know, that's the excuse, if you like. The other important thing is that the coal industry is very big in China, so you have a couple of provinces in the north that are almost entirely dependent on coal for their economies. It's quite hard to shut down vested interests that are quite that big. So it will go slowly. Building new coal is not helpful, but we have to recognize that China has politics too.

CURWOOD: So China is a leader now in renewable energy. How did it get there? To what extent did horrible bad air stimulate that move, by the way?

HILTON: Well, bad air was certainly around when the decision was made. But it was quite a moment, and in the first decade of this century, you had China with an economic model that was beginning to fail. It was the catch up, the very rapid growth, the you know, let's go for GDP growth at all costs and that works for a while. You're making a lot of cheap, low added value goods. You’re really not counting your externalities but after a while that runs out of steam. You've used up all your first advantages, and you have to get more efficient. You have to move up the technology chain if you're going to go on growing, otherwise, you get stuck in the middle-income trap. And so China was looking at this, thinking, what are the technologies of the future? At a time when, as you say, there was also terrible air. So pollution was a thing. People were very, very unhappy, there were big demonstrations. But also the Chinese realized that climate change was real and that China was going to be impacted heavily by it. But also, if the world was going to make a transition to clean economies, it was going to need technologies, and China decided to combine industrial ambition, economic ambition and scientific realism, if you like, and invest enormously in every aspect of every technology that was going to be required for renewables. So that was wind energy, solar, carbon capture, nuclear power, there's a fusion program. There's pretty much everything that you can think of that the 21st century is going to need. And China decided that it was going to be the world's dominant purveyor of those goods and technologies, and it bet the economy on those with great success.

The Panda Solar Station, just south of Datong in Shanxi Province, China, shown here in 2017. (Photo: Planet Labs, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0 Planet Labs, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: So historically, the West got very rich with fossil fuels. The economy really built up with the fossil fuel economy. So given that history and China's advance in the area of renewable energy, what does this put the United States and China vis a vis each other when it comes to economic growth and competition? I mean, to what extent is China in a position to eat America's lunch now for further development?

HILTON: Well, that's certainly what it looks like because, you know, the United States, no doubt, for its own reasons, because it has big incumbent industries, because it has a lot of relatively cheap fossil fuel and industries want to defend their interests, has been a very stop-start player in climate right from the beginning, actually. I mean, you know, the current administration is probably certainly the worst, but right from the start, the United States has been, you know, not entirely a helpful player. It had its good moments, and it had its not so good moments, like signing up for Kyoto, then not ratifying it and so on. So, you know, it is unfortunate for the world that the United States is such a big emitter. It's unfortunate for the United States, I think that it's turning its back on the future because right now, if you look at all the technologies that China now dominates, and which China because it's a very efficient manufacturer and has secured its supply chains, has managed to lower the cost of those technologies. So now it's actually cheaper to generate renewable electricity than it is to generate any kind of power with fossil fuels, and all the technologies that ride on that, the electric economy, and that includes electric vehicles. It includes, you know, all forms of transport. There will at some point be an electric plane, I guess. All of these things and all the associated technologies, like amazing battery technologies, are now dominated by China. Now both Europe and the United States are not short of innovation, but China has scale. It has an enormous domestic market and it has a planning system which committed the entire economy to go in that direction. And the fact is that it's very hard now to compete with China, and if the United States draws back from all this sector, it's going to be very, very hard to catch up, in my view.

CURWOOD: My guest is Isabel Hilton, veteran journalist and BBC presenter, and founder of Dialogue Earth. We’ll be back in a moment with more on China’s dominance in the clean energy future. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

Wind farm in Guangling County, Shanxi. (Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 4.0)

[MUSIC: Joshua Redman Elastic Band, “Shut Your Mouth” on Momentum, Nonesuch Records, Inc.]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the estate of Rosamund Stone Zander - celebrated painter, environmentalist, and author of The Art of Possibility – who inspired others to see the profound interconnectedness of all living things, and to act with courage and creativity on behalf of our planet. Support also comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joshua Redman Elastic Band, “Shut Your Mouth” on Momentum, Nonesuch Records, Inc.]

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

We’re back now with Isabel Hilton, veteran BBC journalist and founder of Dialogue Earth. One of the ways China has been asserting itself as the dominant force in the clean energy future is by forging trade partnerships with other nations, including Canada, which recently cut tariffs on Chinese EVs from 100 percent to just 6 percent. Talk to me about that deal, what does it mean both in terms of geopolitics and economics?

Pictured above is the BYD Song L EV, one of the many vehicles produced in China by a Chinese company. Europe has raised security concerns about the capabilities of a fleet of foreign-made smart vehicles. (Photo: JustAnotherCarDesigner, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 2.0)

HILTON: It's obviously distressing for the Canadian motor industry, and it raises another set of concerns. You know, if you look at the politics of energy these days, we used to talk about energy security in terms of a reliable supply at a reasonable price. So, you know, you secured your oil, wherever you secured it, and when the prices went up, your economy suffered when they went down and so on. So that was energy security. Now, energy security in a renewable age, is a given, because, I mean supply is a given because you install your wind or your solar energy, and you have storage. There is no problem of supply, but what there is a problem of is that all these technologies remain connected. So particularly electric vehicles, remain connected to their manufacturer. You know, they're intelligent machines. And the difficulty with that is that it opens up a whole other set of security concerns when the origins of those technologies are not in a country that you can reliably assume is a friendly country, and that is the case with China. We all have relations with China, but it is in some ways potentially an antagonistic power. Here in Europe we are deeply concerned about the China-Russia relationship because of Russia's invasion of Ukraine. So there are all sorts of questions about security, about energy security, which are to do with critical national infrastructure and access to the grid and the collection of data and the capacity to hit a kill switch, which are embodied in things like electric vehicles. So there is a whole parallel conversation going on about how you secure your systems with those technologies, or can you?

CURWOOD: What you're alluding to is the prospect that, say, a Chinese electric vehicle might have a circuit in it that could be activated that shuts it down. And if you had a whole bunch of those vehicles, they might just be stuck the side of the road because somebody doesn't like it, sort of the way that the satellite telephony stuff that Elon Musk has, it's been used in Ukraine, can also be shut down at a moment's notice, that Starlink can just go away. Am I talking about the right set of concerns here?

HILTON: You are. I mean, one is that there's a kill switch. You know, there's very likely to be a kill switch because the manufacturer needs to upgrade the technology. You know, this connection has to be maintained. So, you know, you get software updates over the air, you get firmware updates over the air. So that's kind of a given. There are also, you know, the possibility that a car could be hacked and accessed and made to commit an act of urban terrorism. You know, a driverless car could be used as a terrorist vehicle. There are all sorts of security concerns about these technologies, and they are now being mapped on to industrial concerns. So again, in Germany, you have the question of the German car industry which is central to the economy, not just in terms of the motor industry, but all the surrounding suppliers, or the Mittelstand in Germany, that's a huge part of the economy, and it's in trouble now because of China. So there's that aspect, but the security aspect, in terms of connectivity, is a real problem. If you look at how the Chinese treat, for example a Tesla car in China, all the data has to stay in China, and there are places you're not allowed to drive that car. You're not allowed to drive it near a military base. You're not allowed to drive it around town if a leader like Xi Jinping is visiting. So the Chinese are very well-aware that there are security issues around electric vehicles.

CURWOOD: So by the way, how important are certain minerals that the Chinese seem to have a pretty good hold of when it comes to the renewable energy business? What about these critical minerals and to what extent are US tech industries, as well as other industries, dependent on China for this material?

An electric bicycle store in China. (Photo: Robbie Sproule, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

HILTON: We have abandoned, we the collective West, abandoned the processing, in particular, of critical minerals to China, because it's a very dirty process. And in that time when the China price was what counted, so outsourcing of manufacturing of all kinds, that phase of China's growth and that phase of relations with the West, critical mineral processing was also left to China. And China has been de-risking its relations with the rest of the world since 2015 and part of the strategy of de-risking was to secure supply chains. So it made a concerted effort to source critical minerals all over the world, particularly in Congo or in Chile, in the lithium triangle in Latin America. It has some at home though it's looking speculatively at Afghanistan security issues, but still. But it's not just the mining, it is particularly the processing that China virtually monopolizes, and that is going to take some time for Europe or the United States to substitute, because we have left the technology to the Chinese. They've got very good at it. And we would be starting from scratch. Other countries would be starting from scratch. So although sourcing of these minerals is not a major problem, rendering them useful is, and they are absolutely essential. They're essential to batteries. They are essential to the defense industry, even if you know, the United States is turning its back on renewables, at least at the official level, it has a defense industry. So yes, every vehicle, everything you drive, everything you fly, you know, uses these critical minerals. So it's a very, very big and potentially powerful monopoly that China has at the moment.

CURWOOD: And that those minerals were also actually in the iPhones or the smartphones that we're using to talk with each other, yes?

HILTON: They're in everything. Your house is full of them. Your pocket has quite a few. [LAUGH] So yes, I mean, they are, in a way, they're as essential to the contemporary economy, to the digital world as oil was to or coal was to the old industrial world. These are the new, you know, you can't do without them.

CURWOOD: So my iPhone speaks Mandarin, apparently, huh?

HILTON: Apparently it does, yes. And the Chinese have passed new rules on the export, they have facilitated export controls on critical minerals, and that includes recycling technologies as well. So they are very determined to keep a hold of it. And this is a weapon that can be deployed at any point. At the moment, we have a one-year suspension in the full deployment of these controls, but you know, that could change any minute.

China dominates the processing of many of the critical minerals present in modern technologies like smartphones. (Photo: Pc1878, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: Let's talk a bit about the geopolitics here and the climate. I mean, to what extent is progress on the climate a political, ideological warfare matter between the US and China?

HILTON: I think that it's very hard to understand why the US administration has taken the turn that it did. It's quite clear that the Chinese decided to build their capacity in renewable technologies, and they did it with great success. The benefits to the world are that they have lowered the price of all these technologies to the point that the price barrier has virtually gone, and that means that countries that have yet to build their energy systems don't have to go through the high emitting fossil fuel stage. They can go straight to renewables. Now, if you're in the oil business, that's a threat. If you're in the coal business, that's a threat. I don't think that political pressure from the United States to keep the oil and the coal business going is going to be very successful, because in the end, business is business, and the administration's efforts to stimulate the domestic coal business in the US didn't work first time around, and I very much doubt they'll work this time around, because those days are kind of over. So there is a geopolitical confrontation which touches every aspect of the relationship, including very fundamentally, the economic relationship. In geopolitical and if you like ideological terms, I think it's greatly to China's benefit to be seen as a responsible climate player. And 20 years ago, China was pointed out as the big, you know, bad boy of climate, because it was a very high emitter. It is still a very high emitter. It still needs to get its emissions down, but reputationally, it's not nearly as bad as it was 20 years ago. Reputationally, it has quite a few cards to play, including its phenomenal installation of renewable energy at home and its supply of cheap and reliable technologies abroad.

CURWOOD: Veteran journalist Isabel Hilton is the founder and former CEO of Dialogue Earth. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

HILTON: Steve, it's an absolute pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Learn more about Isabel Hilton, former CEO Dialogue Earth

- Read Inside Climate News' "Planet China" series

- Dialogue Earth | “The Belt and Road Boomed in 2025”

- Council on Foreign Relations | “What Canadian and Mexican EV Imports From China Mean for the United States”

- Carbon Brief | “China Briefing 5 February 2026: Clean Energy’s Share of Economy | Record Renewables | Thawing Relations With UK”

- Union of Concerned Scientists | “What Does the New Partnership Between Canada and China Tell Us about Future Chinese Foreign Policy?”

[MUSIC: Joshua Redman Elastic Band, “Shut Your Mouth” on Momentum, Nonesuch Records, Inc.]

Wind Power Headwinds

Wind turbines at the Shenandoah Hills wind farm. The project faced a lot of local opposition before going online. (Photo: Anika Jane Beamer, Inside Climate News)

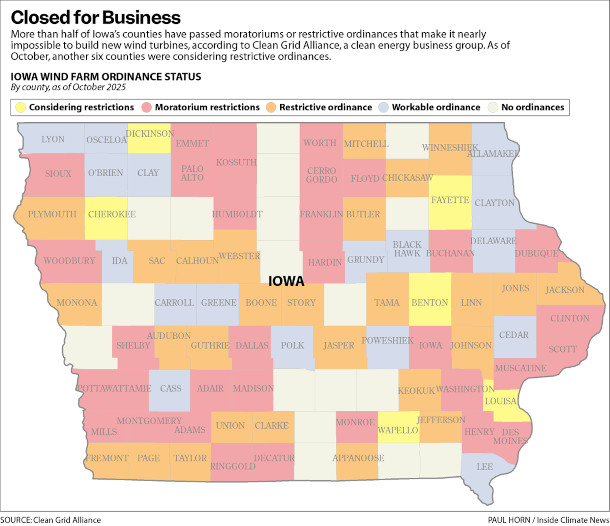

DOERING: As the Trump administration moves to scuttle clean energy, one target is wind. Offshore wind projects have faced shutdowns and onshore wind in the US is also struggling, even in the most wind-powered state, Iowa. As of 2024, Iowa’s grid was about 63% powered by wind, and the state generates more wind power than any other in the U.S. except for Texas, whose sheer size gives it the edge. Windfarms are common in Iowa, thanks in part to how compatible they are with another economic powerhouse in the state, corn and soy farming. But in recent years, a combination of local opposition, anti-wind rhetoric and tax credit phaseouts has led to a steep decline in new ventures. For more, we turn now to Dan Gearino, a clean energy reporter for our media partner Inside Climate News. Dan, welcome back to Living on Earth!

GEARINO: Yeah, good to be here.

DOERING: So the focus of your recent article is Iowa, which generates a huge amount of wind energy, and one project in particular called Shenandoah Hills. Why did you decide to focus on this wind farm?

GEARINO: So there were a total of three projects that were nearing the end of construction this year in Iowa, and it was striking just how little activity there was compared to just a few years ago. If I had gone there four or five years ago, you would have seen a dozen projects that were under construction. So basically, we wanted to find why is it so hard to do these projects? And the way we did that is showing one that barely overcomes all the hurdles. It's hard to develop a wind project, it's also hard to develop a solar project, but it seems especially hard to develop a wind project. So we wanted to see how the development kind of got started, which would have been, you know, about 10 years ago now, and how several years into this process, a whole bunch of opposition started to coalesce, and that very nearly stopped the project.

DOERING: Dan, what did local leaders initially see in the Shenandoah Hills wind farm? What benefits are coming to the area from this project?

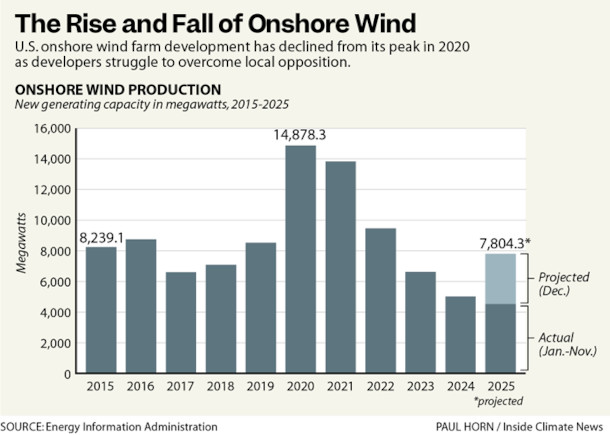

This graph, using data from the Energy Information Administration, shows the last decade of wind farm development in terms of generating capacity. After reaching a peak in 2020, the decline since then has been significant. (Graphic: Paul Horn, Inside Climate News)

GEARINO: So this is a lot of money for schools. It's a lot of money for the county government. Also, a whole bunch of money is going to landowners. This is an opportunity to just retire, or if you're already retired, have a much more comfortable retirement. So the host properties, the landowners where these turbines are built, are doing really well. And if they live in the community, that spending benefit happens in the community, and some of those people do live in the community, so if you're a farmer, then you have more money to buy a tractor, et cetera, et cetera. But I think the main thing in terms of what locals will see is how this creates a lot less pressure to raise taxes, because you're getting this gigantic source of taxes. These are small, in terms of population, there aren't a lot of people in these places. And if you have a project that's hundreds of millions of dollars, it's a lot. And the idea of a project giving a million dollars plus per year to the schools, that is transformative for a school district, a school district that is probably struggling with can it keep staff, it's probably struggling with declining enrollment, and it's just a question of how much do the people in the community value those local benefits? If this is a community where the median age is 45 which is true for Page County, a significant chunk of your population don't have kids in schools anymore, so that affects the debate. But for the places that have had a bunch of these projects go in, it has been an incredible amount of investment that has had a positive effect in so much of rural Iowa.

DOERING: So Dan, please walk us through the reactions that you heard from local Iowans when it came to this new Shenandoah Hills wind farm.

GEARINO: An important thing to remember when you're looking at new proposals for an onshore wind farm is that, in a place like Iowa that already has a lot of wind farms, people who live in rural areas have already seen wind farms all over the place. Certain parts of Iowa, like Adair County, you see hundreds of turbines from certain vantage points where it's just like, they're everywhere. Now those kinds of clusters are in the most wind rich area, so it isn't like that's all over the state, but there's this idea that maybe if a project was proposed 10 years ago, people didn't really know what this looked like. Now they very much know what the end result is like. They also know, for example, if you're driving at night near a wind farm, you see all these red lights, you know, to avoid airplane collisions, all blinking in unison, you know. And it's off putting to many of the people who live there. And a related issue, and I think an even larger issue, is that a lot of the people who are seeing these wind turbines, literally in their backyards, are not necessarily getting paid for them. A lot of the property owners in rural America are investment companies, or they're the heirs of a farmer that lived there two generations ago. It's different from maybe even 20, 30, years ago, when you had a lot more family farmers, and farms tend to be smaller. So that means that even a big project like this one, it isn't a huge number of owners, and a lot of the owners don't live there. It isn't like there are, you know, 40 people showing up and saying, "This is great. This is what I want to do on my property. You all know me. I'm a local person." It's a different dynamic, and I think that has a big effect too. This, like, "Wait a minute, this project means that somebody who lives in Chicago is going to get a check mailed to them every month. But I don't get anything, and I live three miles away?" So it is this sense of money is being made, but some of the residents just feel like it's not fair, the way it's being allocated.

Former Shenandoah Mayor Gregg Connell looks out at the Shenandoah Hills wind farm. Part of the Shenandoah government’s intentions with building the wind farm came from a need to bring jobs and investment to the area. (Photo: Anika Jane Beamer, Inside Climate News)

DOERING: In your article, you mentioned a little bit about the role of anti-wind campaigns, even like on a national level. And websites that publish anti-wind information, some of it not factual at all, and to what extent has that played into some of this local opposition?

GEARINO: One of the things that happens if a community finds out that there's a proposed wind farm, they will go to social media, or they will just Google, and they will quickly fall into this kind of series of messages and photos and memes that are talking about wind energy as incredibly unreliable, incredibly expensive, incredibly dangerous. There was an incident in Iowa where a wind turbine caught fire. And, my goodness, you saw that photo everywhere. That photo was broadcast high and low. Evidence of a wind turbine not working is—it’s a megaphone. The people who are against it have thrown out so many objections, some of which don't necessarily have clear answers. There isn't a ton of body of research about this or that, and that's kind of the point, is to try to stop a project from happening by throwing everything at it, every single possible thing that could go wrong. You know, talking about threats to human health, threats to animal health, effects on farming, effects on, like the drainage systems in fields, effects on, “How is this going to affect my cell signal? My cell signal is really bad. What's going to happen when there are five wind turbines between me and the cell tower?” And all you need to do is get a couple of these local officials to say, “You know what? You've raised enough concerns. Let's research this. Let's do a moratorium, spend some time taking a look at this.” And then, once you pass a moratorium, there's just no development. So in Iowa now, so much of the state has some sort of restrictive ordinance, including many of the most wind rich portions of the state, and I really feel for the local elected officials, like, what are you supposed to do? A lot of these meetings, people don't show up often, and then there's this one issue where your room is full and people are ticked off at you. They're saying you're not answering the questions. They're saying that democracy has failed and they're going to run against you. It's like, this is what's happening, and this is what happened in Shenandoah.

DOERING: And by the way, what do we know about human health and wind?

This map, using data from the Clean Grid Alliance, shows the Iowa counties that have restricted the building of new wind turbines as of October 2025. (Graphic: Paul Horn, Inside Climate News)

GEARINO: Well, that is a topic that is incredibly fraught, and it's one of these things where, when you look at peer reviewed research, you have a hard time saying, here is hard evidence that if you live near a wind turbine, these health effects happen. But we also know that if somebody lives near a wind turbine and there's like shadow flicker from a wind turbine blade, or the red light at night is blinking in their home, and some of the changes in air pressure around, having a wind turbine say, you know, a mile away, or something like that. It's not that these things have zero effect, and I don't think anyone would say they have zero effect. And if somebody is feeling stressed because they don't like this thing that is right outside their window that leads to real, measurable health effects, you could also have somebody who lives in the exact same spot and feels fine because they just they don't mind having that thing there. I suspect whether or not you're getting paid has a lot to do with the extent to which you're willing to adjust. But yeah, it's very difficult to say anything conclusively about health concerns related to wind, and I feel like the kind of blanket dismissal of all health concerns is not helpful. But at the same time, the way that opponents talk about health concerns is if they're proven and sure is also unfounded. So yeah, it's a very messy area.

DOERING: So Dan, you report on all sorts of clean energy for Inside Climate News. What would you say is wind energy's biggest draw?

GEARINO: In some of these windy areas in western Iowa, where it's extremely windy, wind power is strong at night. And if you want to get to a point where the grid is almost all renewable energy, or almost all carbon-free energy, where you have some sort of mix of, say, nuclear, wind, solar, one way you get that is a combination of solar and wind. Solar is super inexpensive on a per unit basis, but it's only available during the day, so you need to have some sort of energy storage to save that for off hours. Wind is something that could conceivably be going strong at three in the morning, and it's not like it's going the same all the time. There are ups and downs with wind, but there's weather forecasting that's pretty good, so that grid operators have a good sense of what to expect. And wind is generally going to be strong at times when solar is weak. So you have this ability through the combination of the two. If you go to almost no new onshore wind development, it just creates this big hole that you have to fill with something else, and what that something else is, at least in the near term, is going to be more expensive, and it's something that we don't necessarily have as much of a core competence with developing. So presents some real challenges.

Dan Gearino is a clean energy reporter who writes for Inside Climate News, covering renewable energy and utilities. (Photo: Dan Gearino)

DOERING: What are we seeing overall, in terms of the trajectory of onshore wind?

GEARINO: If we look across the country, there were a pretty substantial number of projects that went online last year, and this current year will be pretty good in terms of the total number of projects. And by that, I mean it's not just dropping off a cliff. You're seeing some healthy development activity, but a lot of that has to do with what was happening 5, 10, years ago, when some of this development activity was starting. And it has to do with kind of the ebb and flow of tax credits. The concern is that once you get through the projects that are currently in the pipeline, that are currently in construction, or currently nearing the start of construction, there's almost nothing. There are very few projects. And also, when you look ahead, the projects that are getting built, we're seeing a few big projects, these gigantic projects that are hundreds upon hundreds of megawatts of capacity. And this idea of just seeing these smaller projects in more places, you're seeing less of that. So it's like, if you're going to kind of grit your teeth and get through the very contentious process, you want to do it with a project that is just absolutely huge. In 2028, 2029 we're going to see a severe drop off in project, just because the pipeline isn't there of stuff that's earlier in the development cycle, and that is, that's the real concern, because this is a time when electricity demand is going up by a lot. This is the absolute worst time to have the most prolific renewable energy resource in the country kind of just stumbling.

DOERING: Dan Gearino is a reporter with our media partner Inside Climate News, and he covers the business and policy of renewable energy. Dan, thanks so much for taking the time today.

GEARINO: Yeah, thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “What’s Killing Onshore Wind Power?”

- More from Dan Gearino

[MUSIC: Andrew Gialanella, “Swamp and Steel” single, Andrew Gialanella]

DOERING: Just ahead, a wild child named Daisy turns her yard into a haven for nature. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Waverley Street Foundation, working to cultivate a healing planet with community-led programs for better food, healthy farmlands, and smarter building, energy and businesses.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Andrew Gialanella, “Swamp and Steel” single, Andrew Gialanella]

Remembering Mike McElroy

Michael McElroy was an atmospheric scientist and professor at Harvard University. He was also a board member of the World Media Foundation, which produces Living on Earth. (Photo: Kris Snibbe, Harvard University)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Behind the stories and voices you hear on Living on Earth is a dedicated corps of volunteers who help make it all happen, and sadly, cancer has taken one of our most generous and brilliant supporters, Harvard atmospheric science Professor Michael B. McElroy. Mike was a long-time board member of the World Media Foundation, which produces Living on Earth, and a key member of the science and technology brain trust that keeps our reporting accurate. The expertise Mike developed during his 86 years on this planet went beyond science and tech to inspire the creation of Harvard’s undergraduate program in Environmental Science and Public Policy, and its Earth and Planetary Sciences department for more advanced studies. He also brought diverse disciplines together in a university-wide center and launched the long running Harvard China Project to promote Sino-American understanding about energy, the economy and environment. We will miss his invaluable insights about the perils and promises of environmental change especially, of course, about the climate emergency and we will miss him. Thanks for all, Mike.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “Trailblazing Atmospheric Scientist Was ‘a Titan in the Scientific World’”

- The Crimson | “‘A Towering Intellect’: Michael McElroy, Giant of Harvard Environmental Sciences, Dies at 86”

[MUSIC: Dream Sounds, “September Morning” on Dream Sounds, Vol.2, Dream Sounds]

Daisy Rewilds

Daisy Rewilds, published in 2025 by Penguin Random House, follows a young girl’s journey reverting her own front yard to its natural state. (Photo: Taken by Andrew Skerrit, Book Cover via Penguin Random House)

CURWOOD: Many, perhaps most young children love nature and being outside, if given the chance to stomp in a mud puddle or try to catch a frog or a butterfly. And then there is the story of Daisy, a most intense third grade nature girl, the hero in a fable created by author Margaret McNamara. Daisy not only likes nature, she wants to become nature. She refuses to take baths and reverts the manicured lawn of her family home back into the wild, all with a bit of hilarity. Weeds and worms show her family and neighbors the true beauty in nature, chaotic as it can be. Daisy Rewilds by Margaret McNamara is the latest of her three dozen books for young readers, and it was inspired by the concept of rewilding, or allowing outdoor spaces to revert to more natural states. It’s also about the power of acting ecological just about anywhere. She's on the line now from New York City, where she lives, except when in Maine during the long days of summer. Margaret, welcome to Living on Earth!

MCNAMARA: Thank you. I'm so thrilled to be here. I'm a big fan of this podcast.

CURWOOD: So, tell us who is Daisy? What does she look like in her everyday life?

MCNAMARA: Daisy is a kid who goes to school like any other kid, but her passion, her, her heart, is all in the outdoors, and her particular area of the outdoors is not the mountains and the deserts, but it's her own environment, and she is a child who was born with a green thumb. I make a joke about how she was composting her own diapers at a very young age, but she is one of those kids who just gets obsessed, and you've seen it with dinosaurs or with trucks or with ballet and Daisy has that passion for the outdoors and for gardening. And she takes her gardening in a different area than her parents at first want her to do, which is to let the land go back to nature.

CURWOOD: So by the way, for some folks who may not be acquainted with the term, what is rewilding?

MCNAMARA: Rewilding is a movement in conservation where land, or tracts of land, or even small portions of land, are permitted to go to seed, as it were, to go back to nature. So you'll see a lot of people nowadays, especially in areas where wildfires are an issue, they will let their lawns, instead of being grass and turf, be comprised of indigenous plants that are hardier, harder to burn, promote more of a barrier. So kids can do this on a small scale. They could just take a portion of a lawn or space that they might have access to and see what happens when they don't cultivate it. Lot of grown-ups, adults do this on a much bigger scale with indigenous flora and fauna, and really encourage species to come back to where they originated.

CURWOOD: You might say it's just letting the weeds grow.

Margaret McNamara has written over three dozen children’s books, including How Many Seeds in a Pumpkin and The Apple Orchard Riddle. (Photo: Amy Wilton)

MCNAMARA: It's exactly letting the weeds grow, because what is a weed but a plant in the wrong place.

CURWOOD: You know, as Daisy proceeds rewilding, um, she's not very tidy, is she?

MCNAMARA: No, Daisy is not tidy. Daisy allows whatever nature wants to happen to happen. And as that takes hold in the land that she's tending, which is her front lawn, you begin to see the order behind that chaos, the natural order, which is plants that get sunlight and water thrive. There are plants that want to be close to each other, to feed off each other. There are insects who come visit the garden, and that has its own natural beauty and order, just like a meadow does or a lone oak tree. It may not be formal, but it has its own beauty, even in the chaos.

CURWOOD: Now your character Daisy is, may I say, a nonconformist. She has no trouble defying the rules of hygiene, for example. I mean, she doesn't want to wash.

MCNAMARA: She doesn't want to wash. Have you never known a child who also didn't want to wash? I mean, they're out there and the kids who don't like to take baths. Of course, this is a fantastical story, because Daisy starts growing weeds in her hair, and birds come nest in her, so it's not a for real story, but I think it endorses kids who are not averse to having dirt under their fingernails after they come back from digging, and kids who like to get dirty, kids who don't mind getting elbow deep in the soil. And there are kids like that, and there are more kids like that as this kind of movement goes forward. So no, I'm not saying that children should never take a bath, but I'm saying that this child decided not to, and decided to make her own science experiment, and lo and behold, now there's a book about her.

CURWOOD: Of course, now people like Stephen Trimble and Gary Paul Nabhan and Richard Louv would say that the natural place for a child to be is dirty in the backyard, digging from the very youngest age.

MCNAMARA: Exactly, I'm with them. I'm with them, even though I brought up a city child, I'm with them.

CURWOOD: So how important do you think nonconformists are to the success of, of dealing with the environmental emergency we have?

MCNAMARA: Well, that's an interesting question. I'm sorry that they have to be nonconformists to deal with this question. I wish they were the conformists who, just like everybody else, were concerned with the question of the environment. I think that Daisy's rebellion is pretty small. It takes place in the safety of her own backyard. Her parents know what she's doing. Her auntie Betsy is there to aid and abet. And I love that her wise parents call in the real gardener in the family. And so she's getting homeschooled. There's a page in the book where you see Daisy learning about photosynthesis to indicate that she's not missing out on her education. It is kind of a science experiment. So this is good for girls who are interested in the sciences, the STEM subjects. And by the end of the book, everybody in the neighborhood wants to conform to what Daisy's doing. So she does turn it on its head a little bit. She's not too much of a rebel.

Margaret McNamara gardening. She and her family live in New York City and spend summers in Maine. (Photo: Mr. Charles, Courtesy of Margaret McNamara)

CURWOOD: Yeah, I mean, you have Auntie Betsy. How vital is it for adults to nurture and encourage kids who are paying attention to the environment?

MCNAMARA: I think it's crucial. And I'm lucky enough to have a friend whose name is Betsy, who is an avid gardener in Maine, who really has introduced me to gardening and to composting, her favorite subject. So I named this character after my friend Betsy, and she takes the very youngest little babies out into the garden, and she has them digging and watering and being responsible. It's a wonderful thing for children, I think, to be the responsible one who's going to bring the watering can and water the tomatoes, whether it's a tiny little pot outside of your window, or if it's a big bed, you know, in your expansive garden, to engage a child, to do that is a wonderful thing. And you do see initiatives like that. There's one here in the city called Harlem Grown. You probably know the folks involved in that, where empty lots are transferred into gardens and viable areas to feed people, the viable gardening beds to feed children and older people. And so I'm a big advocate of that. I came a little late to gardening in my life, but, you know, now I have the zeal of the convert, so I'm keen to imagine other people bringing their children into the gardens.

CURWOOD: So what's been the response from young readers encountering Daisy on these pages for the first time?

MCNAMARA: Well, I'll admit that the young readers I show this to tend to be kids I've met in Maine and kids who already have a vested interest in the environment. They love it. They love the idea that, like you know, you could start growing plants on your body, which children, you cannot do. But in this book, that's what Daisy does, and they love the imaginativeness of it. And they also enjoy that Daisy converts her neighborhood to her way of thinking, even though she's a child, but it's a very good way of thinking for the environment. A lot of them have been inspired by other young people who've worked as environmental campaigners, and they want to know what they can do. A small thing that you can do is even you know, three square feet of space or less, you can cultivate your own garden. It's not impossible. It just takes some determination and a little sunlight and soil and water.

CURWOOD: And let's face it, a taste for things like lettuce. Mean, it's not exactly easy to get a kid to eat lettuce.

Rewilding is a conservation practice that allows indigenous nature to grow with minimal cultivation. This photo shows the rewilding of Forty Hall, a historic manor house in the Enfield borough of London. (Photo: Christine Matthews, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

MCNAMARA: It's not but if they grow it themselves, then it's a whole different story. Because they see it as a seed. They plant it, they water it, they watch it grow, and then, you know, hey presto, they made food. And I've seen kids who wouldn't be able to swallow a fork full of broccoli, who are entranced by the idea of growing their own food, and who will eat it, and will find the joy in that and the taste in that, and then might not eat it again at the kitchen table, but they like it because they grew it themselves.

CURWOOD: So you know, at the core the book, Daisy Rewilds is a win for the environment. So what's the overarching message from this book?

MCNAMARA: Well, the message is that we ought to look around us and look at the available spaces that we have to invite the vital species back to our land, the species that belong there, whether they're the wild turkeys that appear in the book or simply butterflies, bees, worms. We need them to keep this whole crazy Earth going, and if we don't have them, we suffer. So my big message is, look around you, appreciate the natural world and see what you can do to contribute to its health.

CURWOOD: Margaret McNamara's book is called Daisy Rewilds. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

MCNAMARA: Thank you. It was a wonderful conversation. Thank you so much.

Related links:

- Author Margaret McNamara’s website

- Real life rewilding explained by The Rewilding Institute

- Purchase a copy of Daisy Rewilds (Affiliate link supports Living on Earth and local bookstores)

BirdNote®: Common Yellowthroat

A male common yellowthroat perches atop a treebranch and sings. (Photo: George Gentry, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

DOERING: One of the birds that occasionally brightens Daisy’s front yard could easily be the common yellowthroat warbler, chirping and whistling as it darts and dives to find its meals of insects and spiders. Here’s BirdNote®’s Ariana Remmel.

BirdNote®

Common Yellowthroat

Written by Conor Gearin

This is BirdNote.

[Common Yellowthroat song]

Flitting from stem to stem, a yellow bird in a tiny black bandit mask sings with a voice many times his size.

[Common Yellowthroat song]

Common Yellowthroats are one of the most abundant warblers in North America. They’re adaptable birds, thriving in places that pickier warblers pass over. So it’s easy to find yellowthroats in urban areas. Check for them in marshes, overgrown fields, and brushy areas along streams or trails.

[Common Yellowthroat song]

Many people remember the yellowthroat’s song pattern with the phrase “witchety-witchety-witchety!” During the breeding season, males may repeat the song an earworm-inducing 300 times an hour.

[Common Yellowthroat song]

Only adult males have those bandit masks. But females and young males have light brown backs and those signature bright yellow throats, which helps distinguish them from similar-looking warblers.

[Common Yellowthroat call]

To get a good look, you might have to look down rather than up. Yellowthroats spend most of their time among low-growing plants and shrub branches. There, they feast on insects and spiders on leaves and bark, or grab a snack from a fruit bush.

Common Yellowthroats are warblers that are skillful at living alongside people — making them a great introduction to the songs and bright colors of the warbler family.

[Common Yellowthroat song]

I’m Ariana Remmel.

###

Senior Producer: Mark Bramhill

Producer: Sam Johnson

Managing Editor: Jazzi Johnson

Content Director: Jonese Franklin

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Common Yellowthroat ML527195 recorded by Wil Hershberger, and Common Yellowthroat ML219656 recorded by Bob McGuire.

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2023 BirdNote April 2023 March 2025

Narrator: Ariana Remmel

ID# COYE-01-2023-04-25 COYE-01

Reference:

https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/comyel/cur/introduction

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Common_Yellowthroat/overview

DOERING: For pictures, flit on over to the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related link:

Find the common yellowthroat warbler story on the BirdNote® website.

[MUSIC: Paul Alan Morris, Whalebone, “Riverborn, Tidebound” single, Paul Alan Morris, Whalebone]

DOERING: Please join us for our next Living on Earth Book Club event on Thursday, February 26th! Acclaimed nature writer and New York Times bestselling author Terry Tempest Williams will join us on Zoom to discuss her new book The Glorians: Visitations from the Holy Ordinary, and you can be part of the conversation. In a time of political fragility and climate chaos, the author of Refuge again turns to the natural world for glimmers of hope. From an ant ferrying a coyote willow blossom to its queen, to a black bear cub fleeing a wildfire, Terry Tempest Williams invites us to witness and learn from the fellow inhabitants of our sacred, threatened home. So, join us online for this free event, Thursday, February 26th at 6:30 pm Eastern. Sign up now at loe.org/events! That's loe.org/events.

[MUSIC: Paul Alan Morris, Whalebone, “Riverborn, Tidebound” single, Paul Alan Morris, Whalebone]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Sophie Bokor, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Julia Vaz, El Wilson, and Hedy Yang.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram, Threads and BlueSky @livingonearth radio. And we always welcome your feedback at comments@loe.org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth