Erosion: Essays of Undoing: A Conversation With Terry Tempest Williams

Published: April 27, 2020

Castle Valley, the home of Terry Tempest Williams. (Photo: courtesy of Terry Tempest Williams)

(stream/download) as an MP3 file

Writer Terry Tempest Williams’ latest book, “Erosion: Essays of Undoing”, grapples with the erosion of democracy, science, compassion, and trust, as her beloved Utah red rock landscape faces oil and gas extraction, and the planet faces destructive warming. At a Good Reads on Earth live event, Williams spoke with Steve Curwood about how science and Native knowledge alike can guide us on a more sustainable path, and why erosion also creates an opportunity for evolution towards a better future. After the interview, Terry responds to audience questions.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood and today on Living on Earth we have a conversation with author Terry Tempest Williams about how responding to loss can be a source of empowerment.

But first, your support helps make it possible to bring you this podcast, so please contribute what you can.

Five dollars or more makes a difference.

You can donate right now at LOE.org.

Now for today’s program.

In these times it may seem the whole world is eroding before our eyes. But grappling with profound loss, uncertainty, and change is nothing new for writer Terry Tempest Williams. Her 1991 memoir Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place, set her searing exploration of grief and courage in the arms of nature. Now almost thirty years later Terry has written, Erosion: Essays of Undoing that mourn the erasure of public lands as well as personal losses. As a Writer-in-Residence at the Harvard Divinity School, Terry Tempest Williams divides her time between Cambridge, Massachusetts and Castle Valley, Utah, nearly a mile above sea level on the Colorado Plateau. She joined us at a Good Reads on Earth live event in Cambridge, thankfully before physical distancing made such gatherings impossible.

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: So let's start at Castle Valley, Utah, a place that is so essential to this book. Paint a picture for us, would you, of how it's been shaped by the forces of erosion over these millions of years?

WILLIAMS: Steve, if you and I were having this conversation on our porch, facing south you would see Round Mountain, which is a volcanic plug. It looks like a breast. If you were to see beyond Round Mountain, you would see the La Sals, rising almost 14,000 feet. To the west, is Porcupine Rim. To the north is the Colorado River running red. And to the east with the rising sun is Castleton Tower and a red rock sandstone formation called The Priest and Nuns, created out of erosion. It is a still place; my measure of quiet is to be able to hear the wingbeats of ravens, which we do. And in the spring, certainly the, the songs of the meadowlarks, and at night, coyotes. So it's a wild place. It's also a domesticated place. It's a community of about 250 people, as diverse as you can imagine; but we are known in Moab, Utah, about an hour from us, as the People's Republic of Castle Valley.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

WILLIAMS: And so it's an unpredictable place.

Terry and Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood at the “Good Reads on Earth” live event in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in January 2020. (Photo: Jay Feinstein for LOE)

CURWOOD: So, the red rocks are so seductive, aren't they? It's just amazing. Pictures, though, are tough on radio, but I understand you've brought some sound for us, right? It's a sound of the Earth that you can share with us, straight from the desert. Please tell us about what we're about to hear now.

WILLIAMS: Last fall, Jeff Moore, a geologist from the University of Utah, with four graduate students. They've been doing work looking at the porosity of these landforms: buttes, mesas, in particular, arches, hoodoos in the Valley of Gods, and spires. What is their lifespan? What is the process of erosion? How strong are they? They came to Castle Valley, they brought their seismometers; it would be like a stethoscope. They enlisted two climbers, and they put one seismometer at the base of Castleton Tower. Imagine that it is a 400-foot, Wingate Sandstone monolith, one of the largest freestanding spires in the world. The climbers went up that 400 feet, placed a second seismometer on top, and Jeff Moore and his graduate students listened. What they heard, surprised them. Castleton Tower has a pulse.

[SOUND OF CASTLETON TOWER VIBRATIONS]

And it amplifies the energy that flows through them. It can be local: helicopter, traffic, climbers, wind. It can be planetary: the waves of magma, the waves of the Pacific Ocean, earthquake. So with their permission I brought a recording, and see if you can hear the pulse. It's a vibration. It's a resonance. But as you listen, it mirrors our own heartbeat.

[SOUND OF CASTLETON TOWER VIBRATIONS]

The Castleton Tower red rock formation, near Terry Tempest Williams’ home in Castle Valley, Utah. (Photo: courtesy of Terry Tempest Williams)

Castleton Tower has a pulse. We have a pulse. The earth has a pulse. We took that to Jonah Yellowman, who is the Spiritual Advisor for the Bears Ears Coalition, with Utah Diné Bikéyah, Steve, and I'll never forget him holding that to his ear and just nodding, for three or four minutes. And then he said, "This is what we know." And I think about Western science, geologists; what scientists know, and what native people know. And that we're at this point where those knowledges, those wisdoms, the facts, and the feelings are merging together in a common language. And I think if we could realize that Castleton Tower has a pulse; Bears Ears have a pulse; the ocean, the Atlantic right here, just outside Cambridge has a pulse. Would we treat the earth differently? Would we see ourselves in relationship to the natural world differently?

CURWOOD: I understand you have a passage from your new book, "Erosion: Essays of Undoing" that you'd like to read, Terry; please set this up a bit for us, comes from the very end, I think.

WILLIAMS: You know, what is erosion? It's a natural process. A scientific definition would be the surface of the Earth, worn down and moved from one place to another, through the force of gravity, and I think movement is the key with erosion. It's different than just weathering in place, of wind, water and time. I have to say, I met a geologist named JoAnn Holloway, who works for the USGS, the United States Geological Survey, and she came up with her own definition, which is "the inevitable process by which rock seeks the ocean." Don't you love that? And then a literary definition: "All souls come here to rub the sharp edges off each other. . . . This isn't suffering, it is erosion." Chuck Palahniuk of Fight Club. So this is the end of the book actually. [READING FROM "EROSION"] "Early in our evolution, we discovered as Homo sapiens through need and necessity that our imaginations can summon power. Fire became a dream ignited that enabled us to feed ourselves and gather round to share stories. Stories are power. Power resides in community. When power is denied and oppresses others, we can resist, and when we resist together, something else can occur, something new emerges. This is the essence of erosion and evolution in human time. In geologic time, transformation can be slow and corrosive, or catastrophic and quick. It may be a cataclysmic moment or it may happen incrementally over time. Deep change requires both. And it is not without its ruptures. It can be associated with devastation or determination. It can also be beautiful. Weathering agents are among us. This is a time of exposure. I dwell in Utah. I am witnessing change. Wind does wear down stone." I think it's that idea, Steve, that we are both evolving and eroding together. Wind does wear down stone. We can resist, we can insist change, together.

CURWOOD: Now a central piece of your theme of erosion in this book is the shrinking of national monuments that the Trump administration undertook at Bears Ears. Now, granted, President Obama waited till the last second in his administration, really, to set aside Bears Ears. But when President Trump came in, the Bears Ears designation shrunk by 85% of its original area. Why did these dramatic changes to these designations affect you so, so deeply? And paint a picture in our minds of what we would see if we were there and of course, the iconic piece that everyone calls Bears Ears.

Bears Ears National Monument has been reduced by 85% of its original designation. (Photo: Bob Wick, BLM, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

WILLIAMS: Bears Ears are two buttes, and they look like bears' ears. They're covered with piñons. They are in the middle of what we refer to as Grand Gulch. It's just outside of Blanding, Utah, very near the Four Corners region, where Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona share a common boundary point. They can also be seen from Monument Valley. They're powerful. I've known them as a child, but I didn't know their history until really, relatively recently. The Diné, Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute, Ouray Ute, many of the Pueblo people. These are sacred lands. Bears Ears is a gathering place for many, many nations. And as Johan Yellowman would say, they're not just protecting Bears Ears for their people, but for all people. President Obama heard their cries, as did Secretary Jewell. It was a handshake across history. It was new trust. And it was this commitment that traditional knowledge would be married with Western science in protecting these very fragile desert lands. Trump came in and gutted it by 85%. And now it's open for business. Uranium mining, oil and gas leases, coal; and Bears Ears isn't the only one affected, and I want to read you the list. Chaco Canyon. Hovenweep. Mesa Verde. Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Canyonlands National Park. Great Sand Dunes. Rocky Mountain National Park. Big Cypress. Grand Teton National Park. Carlsbad Caverns. Dinosaur National Monument. Sequoia National Park. All of these national parks and monuments are being affected by oil and gas leasing, in the parks and outside the parks. This is, 25% of the greenhouse emissions are excavated out of our public lands. If we were to halt oil and gas leases on our public lands, that belong to all of us, and we have to keep in mind before they were public lands, they were native lands, we would stop 450 million tons of climate pollution.

CURWOOD: You point out that there's all this carbon, gets spewed into the atmosphere from the excavation and drilling and extraction from public lands. And tell me about, back in 2016 when you and your husband Brooke decided to take a unique stand against the erosion of public lands and the leasing of public lands for oil and gas development, by purchasing the leasing rights to, what, more than 1100 acres near your home there in Utah, to be developed by the Tempest Exploration Company, LLC. Not for fossil fuels, but apparently for the energy that will fuel the moral imagination, you wrote. What inspired you to do this?

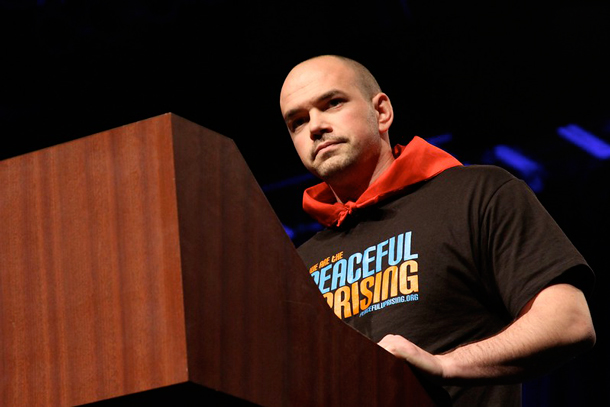

Tim DeChristopher, also known among climate activists as “Bidder #70”, served nearly 2 years in prison for bidding up oil and gas leases on 22,500 acres of public land in Utah’s redrock country, with no intent to pay for them. “Erosion” features a transcribed conversation between DeChristopher and Terry Tempest Williams, about courage, democratic participation, and building a better world. (Photo: Linh Do, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

WILLIAMS: Rage? . . . I think anger goes a long way, and with a name like Tempest, I have to be careful. You know, we belong to a community; eight years prior, a young man, college student at the University of Utah named Tim deChristopher, was part of a protest with the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, protesting, again, oil and gas leases on fragile desert lands in the Colorado Plateau. It was snowing, he went inside, the lease was going on. He walked in, someone said, "Are you here to bid?" and he said, "Why, yes." Saw these lands that he knew by name, and bid them up to fair market value -- he was an economics student -- as an act of civil disobedience. He served two years in prison for that. Eight years later, Brooke and I were part of a protest with our students at the University of Utah in the Environmental Humanities program, sponsored by many groups in Salt Lake City. We went in to protest. Being an introvert, I went into the shortest line; it ended up not going where the protesters were, but where the oil and gas lease was being held. I found myself sitting next to the CEOs of major oil companies. The protesters disrupted the lease, they were asked to leave; they stayed. They protested again, interrupted, disrupted, and they were asked to leave and they were forced out by the police. I stayed inside. I listened, and watched, the vile language, the misogyny, the racist language. I was appalled. I, too, knew these lands by name in our very county, Grand County in Utah. I also knew that if we waited until after the auction that we could go to the Bureau of Land Management and purchase them on a remnant sale. We went in for the remnant sale, got out the map, saw the key parcels in terms of endangered species and in terms of wilderness value, and we purchased, as you said, 1,120 acres, on our debit card --

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

WILLIAMS: -- hoping to heaven that we had enough to cover it. And it was $1.50 an acre. That, these are our public lands; that's cheaper than a cup of coffee, certainly here in Cambridge. And we immediately formed the Tempest energy company, LLC. The BLM, because we said we would not develop these leases untel science could prove to us that the oil and gas was worth more above ground than below, they took that as an offense, even though many of those men -- and they were men, that I was sitting next to -- had no intention of developing those leases until the price of oil went up; nine months later they revoked our leases. Through the Freedom of Information Act we learned that no leases have been revoked since the 1920 Minerals Leasing Act but ours. We've appealed the decision. It's now before the Board of Land Appeals in the Department of Interior. It's now going on four years. And we're about to put some pressure on, with a very friendly administration right now, as you know.

“Erosion: Essays of Undoing” follows in the spirit of other books by Terry Tempest Williams, including “When Women Were Birds: Fifty-four Variations on Voice” (2012), and the environmental classic “Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place” (1991). (Image: Courtesy of Sarah Crichton Books)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] So, you repeat over and over again as a mantra, really, as a prayer, the phrase that "we are eroding and evolving all at once," throughout this book, "we are eroding and evolving." Why does that feel so vital, to have a mantra like that?

WILLIAMS: Hope is not a word in my vocabulary, I have to tell you. Faith is. I remember my great grandmother, a Mormon, born in Mexico, said, "faith without works is dead." But in the middle of this erosion of democracy, of decency, of science, all the things that you and I care about, I think back to home. Castleton Tower, The Priest and Nuns, Round Mountain, Porcupine Rim, the Colorado River, Monument Valley, Grand Canyon, Bears Ears. There is beauty in erosion. And that has been evolving over time. So I think it takes us to our essence. It may take us to our knees; our consciousness is evolving. And I think it's not so much about hope as knowing where hope dwells. And I think for me, hope dwells in community. I don't know about you, but there are moments where I wake up and I think I don't know if I can get up today, you know? Despair is very real. But that is the limits of my own imagination. Imaginations shared create collaboration; in collaboration, we create community, and in community, anything is possible.

CURWOOD: So Terry Tempest Williams, we've been asking you a lot of questions tonight. But since you wrote in the preface of, of this book, that it is a book of questions as I recall, I'd like to ask you, what is your question, if you could pick one for this moment?

WILLIAMS: How do we find the strength to face our grief? How do we find the strength to bear our broken hearts, whether it's with what we're facing with a loss of species, with what we're facing with rising tides. We're going to be facing some very hard things in the future. And I, I hope that we have a consciousness that can rise to this moment. That's the question I have: how do we strengthen one another? How do we find the courage to act? How do we support one another? How do we find the strength to not look away? To stay steady? And here's, here's a story. One of the things that Jeff Moore said, Jeff Moore's the geologist that found the pulse with his graduate students. Five of them; they came to our house for a cup of tea. And as we sat there, he said, "Terry, there's something I want to ask you. We have found a piece of information and we don't know what to do with it. We do not have the language to articulate this to where we don't sound soft-headed." Here's what they found, if I understand it. Castleton Tower has gone through millions of years of fractures, shearing, ice, wind, water. There was another tower next to it, it is gone. It has just been whittled and whittled and whittled into this perfect point. What they have found, through algorithms and through their resonance studies, is that it has now achieved a steady state of stability. I mean as a writer, metaphorically that is so exquisite. So if we are in this process of eroding, can we, too, find this steady state of stability, calm, consciousness.

Formations in Arches National Park. Utah’s red rock landscape has been whittled into fantastical shapes over the course of millions of years of weathering and erosion. (Photo: Stephen Walker on Unsplash)

[MUSIC: Doctor Turtle, "The Ants Built A City On His Chest", The Double-Down Two-Step, CC BY 4.0]

CURWOOD: You're listening to our conversation with writer Terry Tempest Williams, about her book Erosion: Essays of Undoing. After the break, the audience has some questions for Terry.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners and United Technologies combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

CURWOOD: Now we return to our conversation with Terry Tempest Williams in front of a live audience in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she answered some questions from the audience.

We have a question here that asks, could you please share your thoughts on the idea of East Coast people being different than the middle of the country? How do we deal with this polarity?

WILLIAMS: Well, first of all, you can find a New York Times here. That's not the case in the county where I live. That's a tough one. And I don't live in the middle of the country. I would say I live in the interior West. I think It's a different vocabulary. People in the American West know immediately what public lands are, federal lands. I mean, the state of Nevada is 84.6%. owned by the federal government. You understand why there's a hostility. Why you have a Bundy standoff, by the way they're relatives, as is Mitt Romney.

CURWOOD: On which side?

WILLIAMS: My grandmother's.

CURWOOD: As is Mitt Romney?

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

CURWOOD: So he left. Well, he left Salt Lake to come to Massachusetts, and then went back to Utah. So maybe his experience reflects what this questioner is, is getting at.

WILLIAMS: Mitt Romney does not understand public lands. Otherwise he would be supporting them because over 80% of the state of Utah, and Utah's almost 70% on public lands, appreciate them and support them and I think he was fearful that he wouldn't win a primary election. And therefore he put on a hat that said, Make America Great Again, a cowboy hat, and went the way of a minority of a few of what I call the frontier Mormons in San Juan County. That's one example. But I think that I find people more reserved here than I do in the West. You know, I think a more interesting question right now is the rural urban divide. I was just in Louisiana with a woman named Becky Duet, who I love. She's Cajun comes from Cajun country lives on the bayou in Galliano. I met her when I was doing a story on the BP oil spill. She's very, very sick and has been given a time period, but I do have faith in her spirit. Her cajun community were sprayed every night with dispersants by the Coast Guard, and that wasn't under Donald Trump. That was the Obama administration. When I walked around her neighborhood and, and as we went through the bayous, everyone's voting for Trump, including Becky. And when I sat down and said, Can we talk about this? You know, she said, for the first time, we feel seen. And I think that's something for those of us who are progressives to think about, and to not stereotype. Many of my own family members in Utah, feel unseen, my brother felt unseen. And I think part of his erosion and his death by suicide was a result of that. And so I think we have to really see each other not as urban or rural or Northeastern or Western, but as Americans, as planetary citizens and most importantly, human beings. Regionalities I love. I think it shows our distinctiveness. But I am not equipped to say the difference between Easterners and Westerners. I think inevitably it leads to stereotypes. And as a Westerner, I have been stereotyped for a long, long time.

Social distancing in the desert. (Photo: courtesy of Terry Tempest Williams)

CURWOOD: Well, of course there's there's much more that brings us together. There's so many ways that we are similar, as opposed to being divided. We have a question here. Rachel asks, How can we help foster a felt connection to nature as people increasingly live in cities, and often don't have access or time to reach more wild places?

WILLIAMS: I mean, one thing I would say about, really the endangered outer landscape and the maybe impoverished inner landscape is direct experience. I think that's really, really important. I just have spent the last six weeks at home in the desert There's nothing like being there outside with the weather with other creatures, eye to eye, I try and have one eye contact a day with another species. So I think that when you when you are with other species, there's a beautiful when I taught on the Navajo reservation, there was a poem that I remember a first grader made of seeing herself in the eye of a cricket and the reflection of that. And I think it's that idea of reflection, being in a quiet place where your imagination is piqued. You know, certainly we're all victims. My friend Jack Turner, who wrote 'Abstract Wild' calls us all cyborgs that are connected to our phones and our screen. That's obvious. Social media, I think creates a lot of anxiety among our young people. But I think direct experience and ecological literacy To know the names of things, birds, geology, plants, to have a rich outer life so that you have a rich inner life. The specificity of this beautiful broken world, I think helps us connect with something so much larger than ourselves. And I think that is a spiritual relationship, both to the land to each other and to the self.

CURWOOD: So Michael says, we see erosion as a wearing away as we erode morals, political beliefs. Talk to us about how we can see this for good and not leading to a lesser place in these times.

WILLIAMS: I mean, what comes to my mind is a year ago, after my brother, his death by suicide, my father did not want to live. My father is 86 years old and a year ago he just said there, there is nothing left for me. On December 16, he got married. And at 86 to have one of your last gestures be love, I think is erosion and evolution. And you know, my mother has been gone since 1987. They had a beautiful marriage. He's been with a beautiful woman for the last 20 years. And he woke up the day after Thanksgiving. And they've been living together for the last 10. And he said, Will you marry me? And she said, Yes. And it was the most wonderful, joyous, beautiful day. And, you know, we went to the courthouse, and I just thought that seems rather sterile. So I went and got these huge plumes of cedar, and wrap them with red ribbon, carried them in a basket. I guess it's the Mormon in me, you know, favors, I don't know. And there were 13 of us, four generations, and both families. And when we walked in, the judge came in and said, he whispered to me, what cult is this? I just love that. And so, you know, I think erosion, at the point where you think there is nothing left, there is love and risk. And I just think my father was a beautiful example of that. And I think there's parallels in all of our lives, the resiliency, even the resiliency of this planet. It will be here long after we are and that thrills me. I actually think the nitrogen cycle is a beautiful form of erosion. And that's more than enough for me.

Terry signs copies of “Erosion” after the “Good Reads on Earth” event. (Photo: Jay Feinstein, Living on Earth)

CURWOOD: This person says, I feel often so enraged at those who don't take nature seriously. That my love for nature is overshadowed by rage. How can I reconnect to the reason why I fight?

WILLIAMS: What a great question. Willie Gray-eyes is a hero of mine. He lives at Navajo Mountain, one of the most remote places in the lower 48, that spans both Utah and Arizona. After Donald Trump gutted Bears Ears by 85%, I went down. And I saw Willie and I said, Willie, what do you do with your anger? And he said, Terry, it can no longer be about anger. It has to be about healing. And I said, Willie, that sounds so passive to me. I said, What do you mean by healing? And he said, if you have a splinter your heel, and you don't take care of it, it's going to fester, it's going to get infected. And ultimately, if it goes deep enough, you may lose your foot. But he said, If you locate the source of your pain and extract it, then you will heal. And he said, we have to go to the source of our pain. And, Steve, I think that goes back to what we were saying about America's relationship, our relationship to the history of African Americans, to our history with native people, to our treatment of women, and to really heal in this country. Also the disparity of class, and to really go to the source of where our pain is, and not blame it ultimately, on Donald Trump or the United States Congress, but to really look toward each other in our own communities on that scale. And I know for me, I remember after nine women in my family had all had mastectomies and seven were dead, I had a rage I didn't know what to do with as a young woman of 30. And as the matriarch of my family. They all died of cancer and I remember going to the test site to commit an act of civil disobedience, I had to do something I had to act.

CURWOOD: This is the atomic test site.

WILLIAMS: Right, at the Nevada Test Site, the atomic bomb. And what came into my mind was sacred rage. You know, how do we turn our anger and employ it into a sacred rage? How do we take our anger and turn it into right action? And that that really was a turning point for me. Again, engagement is my prayer.

CURWOOD: Before you go, someone's looking for a bit of advice and this is advice for the partner of Tim DeChristopher, you referred to him and, earlier he was a student who bought leasing rights there in Colorado in wound up in jail, actually has come to the Cambridge area. So the partner of Tim leads a conversation project for those of us questioning having children, now, in this age of catastrophe. How do you advise?

Terry Tempest Williams at home in Castle Valley. (Photo: courtesy of Terry Tempest Williams)

WILLIAMS: I love Megan, who is Tim's partner and she's also engaged in public office. And I think she's an extraordinary leader and I expect her to both run and be senator of the state of Rhode Island. And she has been talking about families and bearing children. And I think it's a deeply personal decision, and it's every woman's decision, and certainly in partnership with the beloved. I can only speak for myself. Brooke and I chose not to have children. Every time we made love, it was a conscious choice. At 50 I became a mother. And we adopted Louis Gakumba. We all adopted each other and re-imagined what family looks like. And Louis is now 38. He's married to Rosette Kibamba, and they have two beautiful children, Amalka and Sheja, his birthday is tomorrow. He's one. I could never have imagined that I would be a grandmother. Nor that at that moment, um, you would really reimagine family in a non traditional way. So I don't think you have to give birth to children to have children in your life. I think the women who have children and men and women and women and men and men, you know, I think it's about imagination and what that looks like, and I I have no advice. I would always side on love and whatever that however that manifests, a love for the planet a love for a child, a love for one another. A love for this moment shared.

CURWOOD: Terry Tempest Williams is the author of Erosion: Essays of Undoing, Refuge, and numerous other books and she's currently a writer in residence at the Harvard Divinity School. Terry, thank you so much for taking this time.

WILLIAMS: Thank you, Steve.

[AUDIENCE APPLAUSE]

[MUSIC: Doctor Turtle, "His Last Share Of The Stars", The Double-Down Two-Step, CC BY 4.0]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Candice Siyun Ji, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts, and Google Podcasts- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And you can find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

Links

Outside | “This Rock Has a Voice And You Can Listen to It”

NYTimes op-ed by Terry Tempest Williams | “Keeping My Fossil Fuel in the Ground”

About Utah Diné Bikéyah and its advocacy for Bears Ears National Monument

A coalition of Bears Ears advocates is suing the federal government to restore the national monument

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth