Backyard Tigers in America + The Lion in the Living Room

Published: May 27, 2020

The US Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that more tigers live in America than remain in the wild. Most live in small cages like the one pictured. (Photo: Rachel Nuwer)

(stream/download) as an MP3 file

Private ownership of big cats is completely legal in several US states. In fact, experts estimate more tigers live in captivity in the United States than remain in the wild. Bobby Bascomb speaks with investigative journalist Rachel Nuwer, host of the podcast “Cat People”, about the exotic predators living in roadside zoos and backyards.

Also, America is a nation of cat-lovers, but the reality is that they don’t always bother to love us back. They don’t need to, as we provide for them anyway, according to the book, The Lion in the Living Room. Author Abigail Tucker shares with Steve Curwood how house cats came to thrive in a human-dominated world, and how we didn’t tame them -- they tamed us.

BASCOMB: Hi, I’m Bobby Bascomb and today on the Living on Earth Podcast we’ll take a look at the phenomenon of owning big cats, including lions and tigers, right here in the United States.

Also, a chat about a cat most of us are much more familiar with, the lion in the living room.

But first, your support helps make it possible to bring you this podcast, so please contribute what you can.

Five dollars or more makes a difference.

You can donate right now at LOE.org and thanks!

[THEME]

BASCOMB: Tiger King is a Netflix documentary series about the infamous Tiger breeder Joe Exotic. The series has taken America by storm, with more than 34 million viewers within the first 10 days of its release. The show explores feuds between big cat owners and a murder for hire plot. The series is popular but it’s also been widely criticized for its lack of objectivity setting big cat breeders and big cat sanctuaries on an equal plane. Still, the issue of private big cat ownership is very real. Investigative journalist Rachel Nuwer hosts Cat People, a limited series podcast that explores big cat ownership in the United States. She joins us now from Brooklyn, New York. Rachel, welcome to Living on Earth

NUWER: Thanks so much for having me.

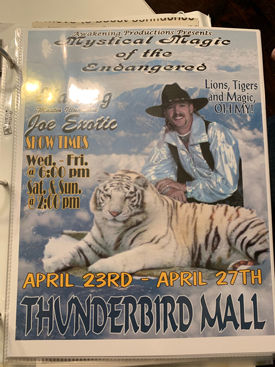

Joe Exotic is the focus of the Netflix documentary series Tiger King. He was a major player in America’s tiger breeding business until he went to prison for his involvement in a murder-for-hire plot. (Photo: Rachel Nuwer)

BASCOMB: So, Rachel, how many big cats are living in the United States right now, roughly?

NUWER: This is crazy. But we actually have no idea how many big cats are living here, you know, in backyards, truck stops, like even in people's like basements. But a few years ago, the Fish and Wildlife Service did estimate that there are more tigers in the US than there remain in the wild. And researchers think there's about 4,000 tigers remaining in the wild around the world. So yeah, there's probably more than 4,000 Tigers here in the country.

BASCOMB: Well, you have a great podcast called Cat People in which you profile a few people, a few big cat owners. Can you tell me about one of them? How did they decide to own a big cat, a tiger, a bobcat and you know what made them want to go down this road to begin with?

Joe Exotic’s roadside zoo is in Oklahoma, one of four states with no laws restricting big cat ownership. The others are North Carolina, Nevada, and Wisconsin. (Photo: Rachel Nuwer)

NUWER: Sure thing so I kind of think about big cat owners as falling into one of three categories. The first category is people who just really love these animals, like truly they love them. They often are interested in conserving the animals, they want to help the species. I met a woman, for example, named Deborah Pierce. She lives in South Carolina. And she just you know, since she was a little girl, she loved lions. And finally, she talked her husband into getting a baby lion cub. And then shortly after, she also got a baby mountain lion to keep the lion company. And, like, right from the beginning, things just went terribly wrong for Deb. You know, like there was a landslide that took out her cages that she had built for these animals. She realized that she had underestimated how much it costs to feed them. Like as they grew like they eventually ate over $5,000 of meat a year. Veterinary bills just like piled up. You know, we're talking over $10,000 a year on vet bills. Eventually, the stress contributed to Deb's husband leaving her and now she can't travel. She can't move. She can't really do anything. Like she's almost like in a cage of her own making because of these animals. But the thing about Deb is, you know, she was motivated because she loves the animals, she wanted to be near them. And people like her are also motivated by the desire to contribute to their conservation, they think, okay, these animals are endangered. So if I can have one, if I can make more, and keep them safe, I'm helping that the survival of the species.

BASCOMB: I mean, a lion in a cage in South Carolina isn't really serving its ecological purpose. So I mean, what use is it to the species as a whole if these animals are in a cage far away from their natural habitat?

NUWER: It's really not. I mean, it's not useful at all for conservation period. You know, I write a lot about poaching of wildlife in places like Southeast Asia and the exotic pet trade is just a booming market around the world. And once that, like lizard or whatever is snatched from the wild, it's dead ecologically speaking. It's not playing any more role in its habitat. It's not perpetuating the species, and the same goes for all these excess big cats in the US, you know, they're just over here in their little bubble not helping conservation whatsoever.

A lion in a roadside zoo. (Photo: Rachel Nuwer)

BASCOMB: Right. Well, that that makes perfect sense. You said there's three categories of people, what are the other two.

NUWER: So the other two are kind of, think of the kind of person who would go out and buy a Ferrari, to show off and to try to be special. It's people who want to stand out from their neighbors who want something to kind of affirm their uniqueness and their coolness and toughness in the world. People will start calling themselves you know, like, I'm the lion woman, or I'm the tiger man. And that's what they become known for. And it's just, it's a way to assert themselves in the world. The last category of people are really the breeders and dealers. These are the Joe Exotics of the world, the people who are in this business, for business, to make money.

BASCOMB: What about animal welfare? I mean, how are these animals usually kept? Are they treated humanely would you say in the whole?

NUWER: Definitely not, unfortunately. This industry is built upon cruelty. So the reason why there are so many pet tigers in the US is not necessarily because there's so many people who are dying to have a tiger. It's because of this cub petting phenomenon. You know, you go to these roadside zoos, you take a selfie with a tiger, you pay like 100 bucks for 10 minutes to cuddle the cub. And then you know, it's the next person's turn. So to produce all these cubs, you know, female tigers are just repeatedly speed bred. As soon as they have a litter of cubs, those cubs are taken away, often within you know, an hour of their birth and bottle fed. The cubs themselves have a terrible life. They often have ringworm, they're malnourished, sometimes they're drugged into submission, you know, so they won't be biting kids that are playing with them, or they're just completely exhausted from being passed around all day long. So there's definitely an element of animal cruelty in the industry.

Cub petting experiences offered by roadside zoos incentivize the continued captive breeding of big cats. (Photo: Rachel Nuwer)

BASCOMB: What is the legality of owning these animals here?

NUWER: About two thirds of states have laws banning big cat ownership, then I think about a dozen have laws saying like, okay, well, you can have a big cat, you can have a tiger, whatever, under these certain conditions. And then there are four states that don't have any laws at all. So you can like get whatever you want. It might be harder to get a dog then a tiger.

BASCOMB: Wow, that is that's a crazy notion. And what are those four states? Where can anybody just go get a bobcat? A tiger, a lion, if you feel like it?

NUWER: Those four states are North Carolina, Wisconsin, Nevada and Oklahoma.

A tiger cub. (Photo: Rachel Nuwer)

BASCOMB: Wow, so really all over the country then?

NUWER: Yeah, exactly. I mean, yeah, it's I don't know why you wouldn't have laws about this. I think people just haven't really thought about it in the past and it's more recently become sort of like a states rights issue and you know, like individual citizens rights issue, like "you can't take away my guns, you can't take away my tigers" kind of thing.

BASCOMB: Now, this is obviously a public safety concern. I want to play a clip from your podcast. This is a 911 call from Ohio.

911 OPERATOR: 911

KOPCHAK: Yeah, this is Ms. Kopchak on Kopchak road, and we live next to Terry Thompson, and there's a bear and a lion out.

911 OPERATOR: There's a bear and a lion out.

KOPCHAK: Yeah, right up behind us.

911 OPERATOR: What's your name?

KOPCHAK: Kopchak

911 OPERATOR: And it's behind your house?

KOPCHAK: Pardon me?

911 OPERATOR: Is it behind your house? Is it behind your house?

KOPCHAK: Yeah, it's up in and they're chasing Terry's horses.

911 OPERATOR: Okay, I'll send them over.

BASCOMB: So what's happening here.

As tigers grow, many big cat owners find that they can no longer properly provide care for their pets. (Photo: Courtesy of Rachel Nuwer)

NUWER: So these are people that, you know, are seeing tigers running down the interstate and are worried and calling in for help. What happened there was this exotic animal owner there named Terry Thompson. And Terry had been arrested for some kind of gun charge. And he actually told the judge, you know, if you put me in jail, the moment I get out, I'm going to release all my animals and blow my brains out. And they're like, haha, whatever, Terry. They put Terry in jail. When Terry got out of jail, he did exactly that. He opened the doors to most of his big cats' cages, and then he committed suicide. And police officers had this situation where they had to then hunt down and kill 18 Tigers, 17 lions, and three mountain lions, plus a bunch of bears, wolves and baboons running around Ohio. So yeah, luckily no humans got hurt in that incident, but very easily someone could have gotten killed. I mean, Terry's place was near a school. It was near hotels. You can imagine.

BASCOMB: Yeah, for sure. That's obviously very, very dangerous.

NUWER: Yeah.

BASCOMB: Well, I mean, we are in the situation now though there's, you know, nobody really knows but thousands certainly of these big cats across the country and relatively unregulated people are getting in over their heads. It seems like a pretty big problem not many people have heard of. But at the end of the day, what should be done about it at this point, do you think?

Rachel Nuwer is an investigative journalist and host of the podcast Cat People. (Photo: Courtesy Rachel Nuwer)

NUWER: So? I think what we really need is federal oversight of this issue. You know, we just need a law like it is or it isn't legal to have these things. And luckily, there is a very strong, ongoing effort to get that into law. There's a bill right now, it's in the house and it's awaiting a vote, but it's called the Big Cat Public Safety Act. And what the Big Cat Public Safety Act would do is first of all, it would ban all public contact with big cat species. So that means no more cub petting. So that automatically would cause the industry to dry up because people wouldn't have any incentive to breed these big cats anymore because there would be no more cub petting. And it would also slowly phase out big cat ownership.

BASCOMB: And how likely do you think that is to pass?

NUWER: Surprisingly, I think there's a really good chance because, you know, it's not just like this tree hugger, animal lover issue. For a lot of Republican lawmakers it's a issue of public safety. So there's actually a national sheriff's organization that signed on to it. There's a former police officer who's really been champing it hard, and, you know, when he gets push back from policymakers, he visits in DC who say, you know, like, "Oh, well, I don't want to take away the rights of my constituents." He's like, "Oh, well, so you're not supporting police officers? You don't want to protect police officers?" And that usually gets a reaction. So it's really great. Because the bill does have bipartisan support, and I think it can pass.

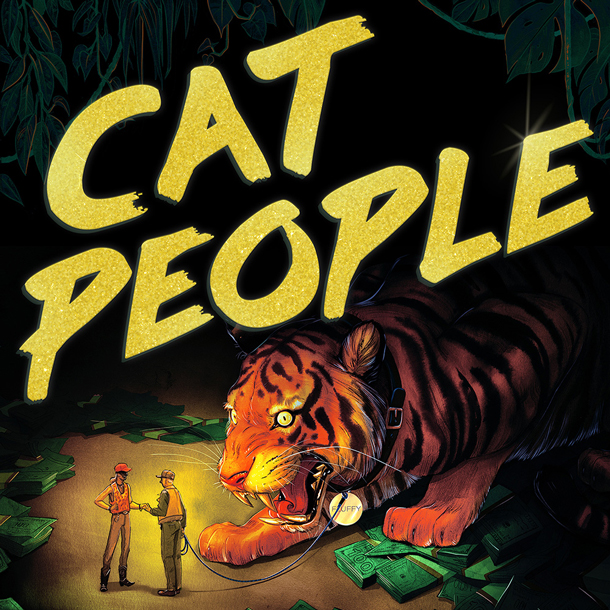

Cat People is a limited series exploring big cat ownership in America. (Illustration Courtesy of Rachel Nuwer)

BASCOMB: Rachel Nuwer is an investigative journalist and host of the podcast, Cat People. Rachel, thank you so much for for sharing these stories with us.

NUWER: Thank you so much for having me and for your interest.

[MUSIC]

BASCOMB: To get the stories behind the stories on Living on Earth as well as special updates please sign up for the Living on Earth newsletter.

Every week you’ll find out about upcoming events and get a look at show highlights, and exclusive content.

Just navigate to the Living on Earth website loe.org and click on the newsletter link at the top of the page.

That’s loe.org.

[MUSIC]

BASCOMB: Plenty of people in the world really love cats, but of course most of them are much smaller than the tigers and lions we’ve been talking about.

Here in the US, house cats outnumber dogs three to one, which seems a bit counterintuitive, considering that Fluffy doesn’t really seem to give us the unconditional adoration we get from Fido.

But Abigail Tucker says there’s a reason why cats came to rule the roost, and, she says, they really do rule the roost.

We didn’t tame them.

They tamed us.

Back in 2016 she spoke with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood about her book.

Even as they’ve comfortably moved into domestic life, cats haven’t compromised too much of their self-sufficiency – they still have the ability to hunt in the wild as feral cats. (Photo: Jennifer Barnard, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Your book is called the "The Lion in the Living Room: How House Cats Tamed Us and Took Over the World", huh?

TUCKER: That's right.

CURWOOD: So, exactly how much of a success story is that of the modern house cat?

TUCKER: It's really kind of a staggering success story because there's at least 600 million and some people think closer to a billion house cats on the planet today which is a shocking number for an animal of any kind. It's especially shocking, though, because house cats are, of course, felines. In nature, felines are relatively rare because they tend to sit atop whatever ecosystem they're in, and they have these huge protein requirements that they have to satisfy, so they're actually rarer than other kinds of carnivores typically, and in the modern age the feline family has been in a lot of trouble because basically they clash with people over meat. And so it's even more spectacular that house cats have been able to carve out a global spot for themselves when so many of their wild relatives, from tigers to sand cats to pretty much any other member of the feline family, have come on hard times in recent years because of their long-standing animosity with man basically.

Cats were originally attracted to human settlements – especially our trash. (Photo: Anton, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, what's the secret of success for the house cat and the role of humans in that?

TUCKER: Well, basically house cats have been able to succeed by sidling up to humanity and harvesting our resources without giving us too much in return and also without compromising their feline forms in a way that would prevent them from surviving without us. Cats have undergone this very interesting and complicated process of domestication, but only to a degree, and they have changed the structure of their brain to get along with us better, but they haven't really changed their bodies that much, and they remain hunters as magnificent as tigers or lions or any other member of the wild feline clan.

CURWOOD: To accomplish this, how did house cats manipulate humans in their rise that they can be such huge numbers, be in our cities and you know be in our houses, or not? How did they do that?

TUCKER: Well, basically, the story goes back about 10,000 years ago to the first permanent human settlements that popped up in the - in the Middle East, in the near east, and basically in these settlements humans began changing the environment in really profound ways and then they started making homes and ultimately planting crops and all the things that would doom many of their wild relatives, and they, as humans, began just taking up more and more space. But rather then fighting with humans and having conflict with humans, cats, sort of lured by our trash came closer and closer into our settlements and started changing themselves to get along with the times rather been struggling against humans, basically as lions and other kinds of wild cats tend to do.

The large members of the feline family are rather uncommon in the wild, since cats require so much concentrated protein – more than 70% of a cat’s diet is meat. (Photo: Steve Wilson, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Yeah, one the things that's a little bit surprising your book, Abby, is that you say that in our society we think of cats as great for going after vermin, mice, and rats and yet at the end of the day where there more cats or more mice, there seem to be more rodents. What's going on? Cats aren't living up to this imputed bargain that I thought we had with them.

TUCKER: Yes, it's really interesting. One of the things that's kind of fascinated me about learning about cat-human relations in a more formal way is all these stories that we kind of make up to make excuses for cats and to explain why we have these animals around and, of course, the classic story is that these animals are very important for vermin control.

Scientists from Johns Hopkins have had this ongoing rodent ecology project going on for maybe 50 years, and they basically have been hanging out with Baltimore's many rats and seeing how they live their lives in these alleyways and watching to see what impacts their ecology. And at one point in the ’80s one scientist who I met with decided to watch the effects of Baltimore's many stray cat on these alleys, and he kind of charted it out, and he found that cats do in fact live in alleyways with more rats and sort of the cat excuse for that would be, oh, that's because they're bravely killing out these rats which are so harmful to human health. But actually what he found was that cats and rats do not fight in these environments at all and that they are more or less peacefully sharing another resource which is trash.

CRWOOD: So, in other words, the Hanna Barbera cartoon series Tom and Jerry, the cat Tom never catches the mouse. This is the reality.

TUCKER: [LAUGHS] Yes, That's exactly the reality.

CURWOOD: You make it sound like, in some respects cats are rats with fur that purr.

TUCKER: [LAUGHS] That's really interesting. I mean, scientists do you think of them, as the pathway that they followed to come and live with us in our settlements, in our cities…Scientists do think of them almost more as animals like rats or pigeons that became affiliated with people without ever really coming under their control.

Cats are highly adaptable and can live in a wide variety of environments (Photo: Michael Frank Franz, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, you know, one of the takeaways from your book is the sheer scope of the cat population, this big rise over the last few decades, and then the feral cat population across the globe. I think you write that in the US there are as many wild or feral cats as house cats, and in Australia it's like a six-to-one ratio of feral cats to house cats. So what's the genetic difference between feral cats and house cats, or is this strictly a matter of upbringing?

TUCKER: Yeah, I mean that's one of the really interesting things. We tend to classify these animals as different, very different in our minds and think of the stray cats as being wilder and in some ways different than our very pampered house pets, but actually, genetically they're exactly the same animal. I talked to scientist who studies, who’s an expert in carnivores and he was doing a study in Madagascar and studying a different kind of animal, and he begin catching these cats in his traps and they were so big and so fierce and so formidable that he actually ran genetic tests on them to ascertain that they were in fact just regular house cats that had been living in the Madagascar interior for, you know, maybe a couple of hundred years but genetically they're just the same kinds of cats as we have in our own homes, which is kind of spectacular. It's this idea that cats can... They're so incredibly adaptable that they can make a go of it in a studio apartment or patrol thousands of acres in the middle of the woods and do fine in either environment.

CURWOOD: Now, you say there are about a billion cats around the planet. How many birds do these cats kill in a given year?

TUCKER: You know, right, so that would be a billion cats - owned pets as well as strays - and the estimates that we get from federal scientists are that these cats kills billions of songbirds per year and also wreak havoc on small mammal populations, and they also kill plenty of amphibians and even insects. But it's also interesting just to think about where the food in your cat's canned food comes from as well. I mean, the fascinating thing about cats and what makes them such unusual candidates for being a globally invasive species is that they're what's called hyper-carnivores, so that means that more than 70 percent of their diet is meat.

Cat lovers who look for strays will find plenty eager to be fed. (Photo: Scott Granneman, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0)

Cats basically eat meat and nothing else, so whether they're going out your garden and hunting a chipmunk or eating something that they get in a can, which could be a wild sardine caught in a far off ocean or a chicken raised a farm somewhere, all these things are meat, and all these things have an environmental impact. So, in a way I think it's a little limited to just think of, “OK, well, my cat is inside so it doesn't eat any wild animals.” That's important, and that's good, but it's not that your cat is existing on, you know, on air and water alone. You know, these animals eat things, and the fact that they do take a toll on the environment and on human resources only makes it more interesting that we tolerate them and even encourage having huge numbers of them around.

CURWOOD: Looking ahead at how cats might involve. What are the indications for what future house cats might look like given their pace of evolution?

TUCKER: Yeah, that's a really interesting question. So, basically one of the things that I learned when reporting this book is that so far humanity has really had no intentional impact on the way that house cats look or behave. We've influenced them certainly because they sort of came to be because of our settlements, but we never exerted any intentional control over these animals, and that continues today.

Felidae is a diverse taxonomic family that includes lions as well as house cats. (Photo: Pauline Guilmot, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

So, you'll see these animals, like I mentioned the scientists who discovered an unknown population of marooned house cats in interior Madagascar, which is not a place where cats normally occur. Those had been deposited by sailors at some points in human history, and those animals were like really big burly house cats with very kind of striped camouflaged looking coats that were making a living for themselves in the wild. And so that's one direction that house cats can go, and becoming almost more lion-like in the way that they look and act if they are reverting to a more wild environment.

At the same time, though, that's not really the evolutionary pressure that's on cats right now. Basically humans are just becoming a bigger and bigger global force, and really where the pay-dirt is, is still in our settlements and living closely with us, and that set of factors does not favor the cats that are big and strong and burly and good at fighting. It actually favors tame cats and meek cats that are able to get into our settlements and live in high densities and not fight so much but have as many babies and eat as much food as they possibly can. And so that's the cat that the 21st century belongs to. While cats can still hack it in the wilderness, the human settlements are really kind of where the future is at, and I think the only way that we as humans have really collectively influenced the feline phenotype, as far as I can tell, is by how fat cats have become as a population, not just our house pets which are frequently in a morbidly obese state, even stray cats and other animals that live in our settlements are really growing larger in a way that doesn't have to do with muscles necessary, but is more just kind of chubbiness.

CURWOOD: Hmmmm, our civilization promotes the fat cat, huh?

TUCKER: [LAUGHS] Yeah, it really does.

CURWOOD: Not just limited to felines, I gather. Hey, on a more personal note, Abby, how did the process of writing "Lion in the Living Room" change how you feel towards cats?

TUCKER: Well, that's an interesting question. I had always been a cat person, and I grew up with cats, and my mom grew up with cats, and it's just been kind of a familial trait, and I still think of myself very much as a cat person. But I don't think that I necessarily gave cats credit for what amazing and formidable animals that they are, even though I write about animals in a professional way and have gone to different places around the world to write about different rarified creatures in their native environment. I was just as guilty as the next person when it came to looking at my cats as little, cute little fur babies and infantilizing them and pretending that they needed help from me.

Abigail Tucker is a self-described “cat person” (Photo: courtesy of Simon & Schuster Publishing)

Now I understand that you know even though I been accustomed to traveling across the world looking for interesting animals, this is an interesting animal that has come to meet me in my living room. This creature is a creature of conquest and a creature that is a global survivor and is sort of an example of how amazing nature is. And I think that in a way, you know, that's a lot more kind of stimulating and interesting than thinking of my cat is just being a kind of slow-witted, furry human, which is how I used to think about them.

CURWOOD: Hmmmm...they're not so slow-witted are they?

TUCKER: They're really not.

BASCOMB: Abigail Tucker’s book is called “The Lion in the Living Room: How House Cats Tamed Us and Took Over the World.”

She spoke with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jay Feinstein, Jenni Doering Merlin Haxhiymeri, Candice Siyun Ji, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari.

Tom Tiger engineered our show.

Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth.

We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio.

Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer.

I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green, and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Links

Rachel Nuwer’s Cat People Podcast

Longreads | “The Strange and Dangerous World of America’s Big Cat People”

The Lion in the Living Room book

The American Bird Conservancy’s official statement about the threat of housecats to wildlife

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth