Farmworkers and the Virus

Published: May 4, 2020

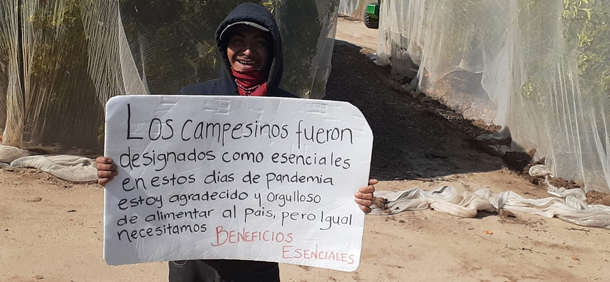

A campesino holds up a poster that reads “Field workers were designated as essential during the pandemic. I am thankful and proud to feed the country, but we also need essential benefits.” (Photo: Courtesy of UFW)

(stream/download) as an MP3 file

Migrant farmworkers are considered essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and if they don't continue to tend and harvest the crops that feed America, there will be food shortages. Many face special risks during the pandemic, as they work in crowded conditions and more than half of them are undocumented, with poor access to healthcare and federal aid. We’ll hear from a longtime California farmworker about his fears and frustrations about working with little protection in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Also, a note on emerging science: as people around the world self-isolate and non-essential work is put on hold, the Earth has grown quieter, according to seismographic data.

BASCOMB: Hi, I’m Bobby Bascomb and today on the Living on Earth Podcast we’ll take a look at how undocumented farmworkers in the United States are extremely vulnerable to the Coronavirus.

But first, your support helps make it possible to bring you this podcast, so please contribute what you can.

Five dollars or more makes a difference.

You can donate right now at LOE.org, and thanks!

[THEME]

BASCOMB: Meat supplies are getting tight in the US as processing plants have become hotspots for the COVID-19 virus, with at least 17 workers dead, thousands more sickened and dozens of meatpacking plants shut down. Meatpacking assembly lines are crowded with low wage workers. Many of them are undocumented immigrants, much like the workers who harvest and process the produce grown in the US. United Farm Workers spokesman Marc Grossman says farmworkers are also at high risk in the face of the pandemic. Marc Grossman joins me now, welcome to Living on Earth!

GROSSMAN: Pleasure to be with you.

BASCOMB: So please tell me first about the average farmworker in the United States. Who are they? Where are they from and what's their daily life like?

Raspberry production in Watsonville, California. Raspberry production often takes place in June-July. (Photo: Courtesy of UFW)

GROSSMAN: Well, even before the pandemic hit farmworkers faced daunting challenges. We know that, you know, they're mostly immigrants today, in very low paying jobs with the exception of a small number that are protected by union contracts. They have few if any benefits, they must live, commute and work under very close quarters often in substandard and unsanitary and crowded conditions. We know from the US Department of Labor that at least half are undocumented, which makes them even more vulnerable to abuse. But all of these factors make them uniquely vulnerable to the pandemic. And when the pandemic began, the UFW first went directly to individual growers who were under a union contract and some companies under contract change, picking practices and styles. Even if productivity was reduced to enforce social distancing, implemented other social distancing practices had training including crew meetings to educate workers about what they should do. But those responses only highlight the urgent need for more widespread action at non-union companies and there although some employers are stepping up, many are not. And you know, we've all seen the shelves of the supermarkets, on paper goods and toilet paper and so on empty, but imagine if the pandemic takes hold in the farmworker community what would happen to the nation's food supply?

BASCOMB: So those sound like really good common-sense precautions to take for essential workers who again, you know, are providing food for the country, but how common would you say those types of precautions are within the industry?

GROSSMAN: You know, we have an expression that the laws on the books are not necessarily the laws in the fields. California leads the nation in protective laws and regulations for farmworkers. Everything from minimum wages and hours to pesticide protections to sexual harassment, but there is too often a gap between what the laws and the regulations and the government agencies require and the actual enforcement and implementation in the fields.

BASCOMB: And a lot of these workers are here temporarily from other countries and I assume have temporary housing. What does that look like for them?

A campesina harvesting grapes on a California farm. California grapes form part of an industry approximately worth $2 billion. (Photo: Courtesy of UFW)

GROSSMAN: Well, the housing and these are H2A guest workers is usually barracks-style housing, where people are packed in closely together in beds or bunks. It's very difficult to enforce social distancing. And if someone gets sick, unless special preparations are made to quarantine them, then that becomes a big challenge too.

BASCOMB: And if they do get sick, do they have access to health care while they're here?

GROSSMAN: No, you know that that's a big problem because the great majority of farmworkers and non-union companies do not have health care. And, you know, one of the problems on paid sick leave is that some growers have made it difficult for workers to actually claim it. Sometimes they require a doctor's note. But since most workers have no health care, they don't have doctors, or some companies have a waiting period 30, 90 days before new workers can claim sick leave benefits if they exist. So all of those things represent challenges that must be overcome quickly if paid sick leave is going to become a reality.

BASCOMB: Now, you said that as many as 50% of farmworkers are here illegally, how possible is it then that they're putting themselves at even higher risk of deportation right now going to work when there are so many fewer people out and about in the world? Is that something you're concerned about? You know?

GROSSMAN: When on the UFW social media platforms, many workers respond to the news that they're now officially considered essential workers with anger, because they say, well, now they think we're essential workers. But they don't have essential benefits and protections that other essential workers have enjoyed for some of them for generations, minimum wages and hours, The Fair Labor Standards Act the federal law, from the New Deal granting industrial workers something as simple as overtime after eight hours a day excludes farmworkers, back in 1938. And it was only in two 2016 that the UFW got a law passed in California that provides phased in overtime after eight hours a day over a four year period. So these essential workers often do not have the essential benefits that protect everybody else. Hazard pay, hundreds of thousands of workers in the retail food industry have been provided sometimes $1, $2 an hour or more in additional pay, because they're putting their lives at risk by going to work stocking the supermarket shelves. Well, farmworkers are also essential workers and they take their lives in their hands when they go to work. Why shouldn't they get the same recognition?

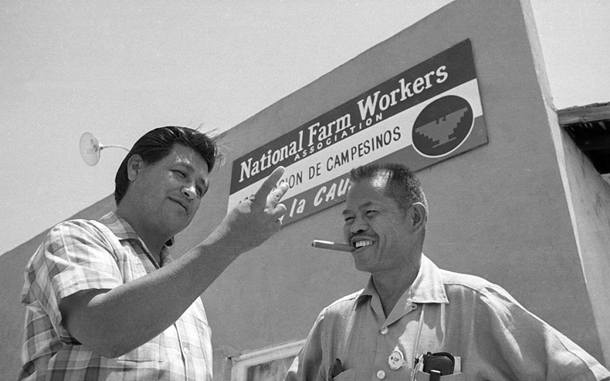

Cesar Chavez and Larry Itliong were leaders in the Delano Grape strikes of 1965. The peaceful strike involved both Mexican and Filipino farm workers protesting against the exploitation of farmworkers by Delano-area vineyards. Thus began a five-year grape strike and later a three-year international boycott of California table grape. (Photo: Courtesy of UFW)

BASCOMB: And how concerned are they that while going to work and performing this essential service, they might get deported on their way? I mean, is ICE, it's still targeting these workers just as much as they were before the pandemic?

GROSSMAN: I believe ICE has indicated that they're holding up on enforcement actions in the interior of the country. But remember, for years there has been a palpable fear by foreign workers just in going to work. So, you know that in addition to the danger of exposing themselves and their family members to infections, many undocumented farmworkers find it very difficult to abandon their fear of being apprehended and deported. You know, last December, the US House of Representatives passed a bill for the first time in decades an agricultural immigration bill that would allow undocumented farmworkers already in this country to earn the legal right to permanently stay by continuing to work in agriculture. The bill is now in the United States Senate, and it was passed on a bipartisan vote, 34 Republicans in the House voted for the measure and it would go along way in eliminating the fear and the terror that undocumented farmworkers live with every day.

BASCOMB: So I mean, it seems like we're in a situation where these farmworkers are considered essential today but could still be deported six months from now when hopefully this pandemic has passed and things go back to normal. Is that really what we're looking at?

GROSSMAN: We hope that Americans use the pandemic as an opportunity to really examine themselves and their society, and equity issues like the denial of essential rights and benefits to farmworkers. That has gone on for too long. So we're hoping that people use this as an opportunity for reflection, much-needed reflection on eliminating the inequities and the injustices that have plagued farmworkers and other people who are vulnerable.

BASCOMB: Marc Grossman is a spokesman for United Farm Workers and former assistant and speechwriter for Cesar Chavez. Marc, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

GROSSMAN: My pleasure. Thank you.

BASCOMB: For more, I’m joined by Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran. Paloma is in Mexico now, riding out the pandemic with her family and has been digging into this story of the Coronavirus and agricultural workers.

Hi Paloma, how are you?

The San Joaquin Valley citrus region has more than 20,000 lemon harvesters. There are more than 700,000 agricultural workers in California, all of whom are considered essential workers during the coronavirus pandemic. (Photo: Courtesy of UFW)

PALOMA: Hi Bobby, I’m good, happy to be safely isolating with my mom and sister. How about you?

BASCOMB: Good, lots of time with my husband and kids.

PALOMA: Nice…

BASCOMB: So, you recently spoke with a farmworker who is struggling through the pandemic. Tell me about him, please.

PALOMA: Right, I talked with a man named Jesus. He is originally from central Mexico but has been an agricultural worker in California for almost 20 years. He makes $13 an hour before taxes at a non-union farm and is just about to start the cherry-picking season then he’ll move to grapes in June. But of course, that’s only if there is enough demand for those products. Already his hours have been cut from 10 hours a day to 8. And he’s really worried about the economy and hopes that it opens up soon.

JESUS: “Si nosotros no trabajamos no comemos."

PALOMA: He says, “If we don’t work we don’t eat.” And Jesus is not just worried for himself. He sends money back to his wife and kids In Mexico each month and that’s their main source of income.

JESUS: “Espero dios y no me enferme y pues yo necesito trabajar para poder mantener a mi familia”

PALOMA: He says, “I hope God spares me from getting sick because I need to work to provide for my family.” He’s really scared.

BASCOMB: Wow, that sounds so stressful. What is he doing to keep himself safe and avoid getting the virus?

PALOMA: Well, I was shocked to hear Jesus say that his employers aren’t providing anything other than soap and water to help him and his co-workers stay safe.

JESUS: “Nosotros de nuestra propia cuenta tenemos que llevarnos pañuelos para protegernos y cuidarnos nosotros mismos”

PALOMA: He’s saying, “we have to buy our own facemasks or wear scarves to protect ourselves and we wash our hands as much as possible.” Some employers are “encouraging” social distancing but it's really hard to distance yourself when you are working in the agriculture industry. It’s a hands-on job that requires teamwork and face to face interaction.

JESUS: “Nosotros trabajamos en cuadrillas de 15-20-25 personas pues si tenemos miedo a enfermarnos. Si nosotros nos enfermamos no tenemos con qué pagar lo que es el seguro médico."

The San Joaquin Valley is the largest cherry production region of California. Most of the United States’ vegetables, fruits, and nuts are grown in California, making California agricultural workers an integral part of the nation's food supply. (Photo: Courtesy of UFW)

PALOMA: He says, “we work tight groups of 15-20-25 people and everyone works closely together, so everyone is scared of getting sick. We don’t have health insurance, if we get sick we would have to pay health care costs out of pocket from the little savings we have.” And I think he feels a bit of resentment about the lack of support. He says the United States is highly dependent on immigrant farm workers like him and he contributes to the economy.

JESUS: “Nosotros también en nuestro cheque nos descuentan lo que es seguro, lo que es médical, todo lo federal también. Osea nos descuentan igual que una persona que tiene documentos ”

PALOMA: Farmworkers pay taxes just like everyone else, he says, including federal taxes and so he doesn’t understand why the federal government is not supporting them as essential workers during this pandemic.

BASCOMB: Jesus is just one person but it sounds like his story is pretty common across the industry.

PALOMA: Yes, for sure. Jesus says he’s also worried for people who work in managerial roles and packing facilities across the commodity chain. And as we’ve mentioned earlier more than half of the fieldworkers in the US are like Jesus and undocumented so they face very similar challenges. Jesus told me that he talks a lot with his co-workers about the virus and fear of getting sick and losing their jobs. And they’re just feeling sad, you know, the missing family that’s so far away.

BOBBY: Right, such a difficult position to be in. Well, thanks for bringing us his story, Paloma.

PALOMA: You’re welcome. Stay safe there.

BOBBY: You too! I’ll talk to you soon. That’s Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran from her family home in Mexicali, Mexico.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, "Lobo Lobo", El Baul]

BASCOMB: We are spending a lot of time indoors these days, and indoor air can affect our health, creativity, and productivity.

For some insights, we'll be hosting a free live streamed conversation with renowned Harvard public health expert Joe Allen.

He’ll be talking about his new book, Healthy Buildings, and exploring how we can design indoor spaces to maximize our well-being.

The event is May 12 at 6:30 Eastern.

To learn more about this and other events in our Good Reads on Earth series, visit the Living on Earth website, at loe.org/events.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, "Lobo Lobo", El Baul]

BASCOMB: In response to the coronavirus outbreak, much human activity has come to an abrupt stop.

In fact, scientists say the earth has actually become more still in the months since we’ve stayed home.

Living on Earth’s Isaac Merson reports in today’s Science Note.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

MERSON: As people around the globe shelter at home, an unusual calm has come to the surface of the earth.

In fact, our reduced activity and physical movement can actually be measured using seismographs, instruments used to measure the minute movements of the earth beneath our feet.

Seismographs are extremely sensitive. They sense vibrations caused by sources as varied as the wind moving across the surface of the earth, the crash of waves on the shore, the hum of pressure as gasses bubble up through cracks and seams in the crust in the earth.

And they also detect vibrations caused by human activities, such as the movement of vehicles or the pounding of industrial machinery.

[MACHINERY SOUND]

Seismographs are incredibly sensitive instruments, and can detect vibrations from sources as minute as the wind blowing across the surface of the earth. The seismograph showing all the blue ink indicates lots of vibration, which is coming from the crater rim of Hawaii’s Halema‘uma‘u Crater. (Photo: Rosa Say, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

All these vibrations create a background which can be hard for earth scientists to tease apart.

But in the weeks since governments have issued orders to stay at home Seismograph data from around the world has shown a tremendous decrease in the amount of these ambient seismic vibrations.

One seismograph located at the Royal Observatory of Belgium showed a greater than 30% decrease in the total background vibrations in the weeks since Belgium instructed its citizens to stay home.

And Brussels isn’t alone. Seismographs from Los Angeles, London, and Barcelona have shown similar or even larger reductions.

Now, in the absence of some of that muddy background data, scientists may be able to gather important information about the influence of other sources of ambient vibrations, such as the exact contribution of the oceans.

[OCEAN SOUNDS]

This may help us better predict future earthquake events, especially in highly populated urban areas.

Update this morning: anthropogenic noise is still low. We also compare the median noise per weekday/hour before/after lockdown! #staysafe #stayhomebelgium pic.twitter.com/iAE1imBuEj

— Seismologie.be (@Seismologie_be) April 6, 2020

In the meantime, the relative stillness of the earth’s crust could allow seismologists to better detect seismic events happening right now,

[EARTHQUAKE SOUND]

as the signal may come through more clearly with less competing noise, like a radio signal with less static.

For Living on Earth, I’m Isaac Merson.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, "Desmontes", El Baul]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Candice Siyun Ji, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Director. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Links

Read more about the California Farm Bureau and the COVID-19 pandemic

Informational Video by the California Farm Bureau for Farmworkers

Link to United Farm Workers of America

Los Angeles Times | Farmworkers face coronavirus risk: ‘You can’t pick strawberries over Zoom’

National Geographic | Farmworkers Risk Coronavirus Infection to Keep U.S. Fed

Nature News | “Coronavirus lockdowns have changed the way Earth moves”

Follow @Seismologie_be to see current seismograph data from the Royal Observatory of Belgium

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth