How the Border Wall Could Harm Wildlife

Air Date: Week of September 13, 2019

The border wall between the US and Mexico follows the hills and valleys of the rugged arid landscape (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

Amid outcries about its immigration policy, the US government is moving forward with an expansion of the border wall with Mexico. Biologists are raising the alarm that the wall can be a dead-end for migrating animals, including some bird species. Host Bobby Bascomb reports from the border on how construction of the wall can disturb nesting birds and damage sensitive habitat.

Transcript

BASCOMB: The US border with Mexico spans more than 1900 miles from the Pacific Ocean off the coast of California to the Gulf of Mexico in coastal Texas. Over a third of the border, nearly 700 miles, currently has some sort of barrier or wall and amid the controversy over immigration the Trump administration has pledged to fill in the rest. I went to the border region to see what that might mean for wildlife in the area.

[WIND SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: I’m standing on a hill at the base of the Patagonia Mountains, about 60 miles south of Tucson, Arizona. Thorny cactus with pink and yellow flowers dot the arid landscape. From this elevation it’s easy to see how the border wall perfectly mirrors the topography of the land, rising and falling with these hills and valleys. Except for a small break at a river, the wall extends as far as the eye can see to the West, some 40 miles to Nogales. But to the east it’s a different story.

SERRAGLIO: Up here on the hill we can look East here and see the point at which the border wall ends out there, it doesn't actually go up and over this really rugged terrain that crosses the border right here.

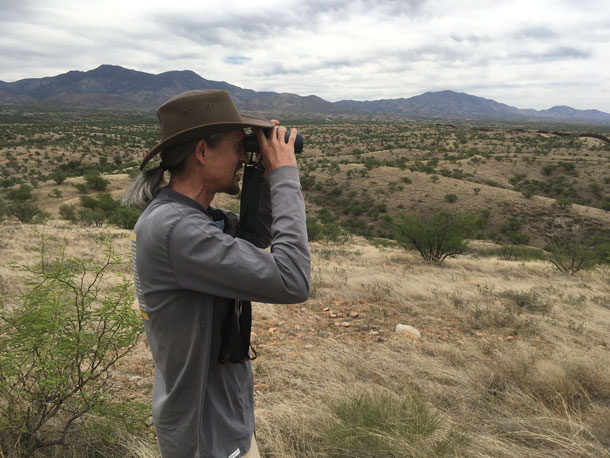

Randy Serraglio from Center for Biological Diversity, looks across the landscape towards the US Mexico border wall. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Randy Serraglio is the Southwest Conservation Advocate with the Center for Biological Diversity. He’s tall and thin with gray hair pulled back under a cowboy hat and binoculars, at the ready, hanging from a strap around his neck. He says this break in the border wall is a lifeline for migrating animals, including jaguar.

SERRAGLIO: This is one of the handful of really prime Jaguar movement corridors, places where jaguars can move back and forth across the border.

BASCOMB: Historically jaguars ranged from Brazil's Amazon rainforest through Central America and as far north as the Grand Canyon. Starting in the 1960s hunting claimed some 18,000 per year in the US and today only a handful of juvenile males are known to live north of the border including el Jefe or the boss, so named by local school kids. Randy points across the wall to the Mexico side of the border.

SERRAGLIO: He was born there and emancipated and came up here as a relatively young and vulnerable male Jaguar at the age of maybe two or three.

BASCOMB: Using camera traps, biologist were able to keep tabs on El Jefe for several years as he grew into a healthy adult while living in the nearby Santa Rita mountains. Then he abruptly disappeared.

SERRAGLIO: And biologists believe the most likely explanation, he came right back through here and went right back to wherever the females are, and then when he got to his breeding prime around the age of seven, he went back to wherever those females are. And that is critically important for jaguars, they have to be able to do that in order to survive, they have to be able to roam long distances and find territories of their own, and yet still remain connected to that core population. And that's why a place like this is absolutely essential for Jaguar recovery.

BASCOMB: The borderlands in general are home to a huge variety of animals including pronghorn, javelinas, ocelot, mountain lions, bobcats, Mexican Gray Wolf, black bears, and bison to name a few. Dozens of endangered and threatened animal species use these rugged, barrier free, mountains as a highway for migrating between the US and Mexico.

The US border wall is strung with razor wire on the US side of the wall. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

SERRAGLIO: There's a herd of bison in the boot heel of New Mexico. And their favorite foraging grounds is on one side of the border and their favorite watering holes on the other. So they often cross back and forth on a daily basis. But if there's a border wall built there, they won't be able to do that anymore. At a certain point, you fragment the landscape enough and you fragment habitat enough and you isolate populations, and they start winking out. That's how species go extinct. I mean, we just know that for a fact.

[SFX DOOR CLOSING CAR DRIVING SOUND]

BASCOMB: Randy and I pile into his pickup truck and drive a few miles down a dirt road to another type wildlife corridor. A lush green band of walnuts, willows, and cottonwood trees hint at the water that lies just below the surface.

SERRAGLIO: These are trees that rely on water, they have to have shallow groundwater in order to survive. So they only grow in these narrow stretches right along the river.

[GETTING OUT OF THE CAR SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: In the monsoon season this river bed would be full of rain water. But it’s the dry season so we stand in the middle of the dusty riverbed to have a look around. Randy lifts his binoculars and points out a small brown and yellow bird.

[BIRD CALL]

SERRAGLIO: Oh, there’s a cute little fly catcher. Oh, yeah. They have a crest in their head. And so they'll perch out in the open like that. And then they'll fly out and catch bugs on the wing and then go back to the same perch again.

BASCOMB: Hence the name flycatcher.

SERRAGLIO: Yeah, they're very acrobatic, they're fun to watch.

BASCOMB: What are those two there?

SERRAGLIO: Those two were kestrels, and one of them had a lizard in its mouth. And the other one was chasing it. There, they just landed up in the tree.

Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb at the border wall in Arizona. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Oh, like the other one is trying to get its dinner.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

SERRAGLIO: Yeah, that's why they were kind of whining. Like, give me that. It could be that that the one was a young fledgling flying around after mom or dad saying feed me feed me. And they're at the point where like, now you gotta start feeding yourself. Get a job.

BASCOMB: Tough Love. Yeah.

[HAWK SOUNDS]

SERRAGLIO: That's the high plaintive call of a gray Hawk, which is a beautiful Hawk that lives in these riparian areas and nowhere else. So it's probably in that big giant cottonwood tree over there. Might even might even have a nest, which would kind of be a disaster.

BASCOMB: A disaster because this riparian habitat teeming with life is also a construction zone. It’s Sunday, so the bulldozers and cranes are sitting idle but Border Patrol is hard at work 6 days a week building a box culvert, a kind of small bridge, across this river. And Randy says all the noise, lights, and cleared land is devastating for wildlife.

SERRAGLIO: See that bank of high intensity lights over there. Yeah, with the shiny covers and everything. I mean, that is completely disorienting for bats and migratory birds and insects at night. You've got these big dump trucks and cranes, and, you know, concrete mixers, and all this other stuff going on here. And they've completely bladed all the vegetation. It's just this big, dusty, you know, wasteland, now it's like acres of just dust now, whereas before, it was this lush vegetation.

BASCOMB: Indeed, nearly all the birds we’ve seen are on the Mexican side of the border which is lush and green with huge trees and a blanket of grass at the bottom of the riverbed. The US side is a dirt road, a pile of gravel, and heavy equipment.

The border wall needs constant maintenance and frequent upgrades. Those construction projects can be disturbing for wildlife in the area. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

[WALKING SOUND]

BASCOMB: We can easily see into Mexico from here because instead of 18 foot tall steel slats, which is much of the wall, the border here is simply a car barrier, waist high pieces of metal sticking out at 45 degree angles from the ground.

SERRAGLIO: When we have our summer monsoon, we have these big thunderstorms and the floods would knock this border wall down if they built it right through there. So instead, what we have here, vehicle barriers that are actually in the floodplain, in the riverbed, and they're this old school, Normandy style, cross hatch, you know, steal things, and they stopped cars from driving through, but you know, people could climb right over.

BASCOMB: And so can wildlife. It’s relatively short with large gaps, which allow water to flow through as well as migrating animals.

SERRAGLIO: So vehicle barriers are much more wildlife friendly. And there's still a road that gets bladed, you know, when they have vehicle barriers, but they're not the kind of, you know, absolute obstruction that the border wall creates.

BASCOMB: Customs and Border Protection recently received 2.5 billion dollars for barrier replacements, which includes repairing damaged walls but it also means “improving” the wall from these vehicle barriers, permeable for wildlife, to the full border wall, steel slats up to 30 feet high and a complete dead end for animals.

This section of the US side of the border wall is a construction zone to build a small bridge across a floodplain. Ecologists say the heavy machinery and disturbance to the land is detrimental for local wildlife. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

SERRAGLIO: They call it replacement barriers, and they're trying to pretend it's not a big deal. But it's a huge difference in the disruption that's caused between, you know, a border wall and a vehicle barrier in terms of wildlife.

BASCOMB: And it’s not just large mammals that can’t get around the wall. Even some birds, including the cactus pygmy owl, will have a hard time getting over a higher wall.

SERRAGLIO: The border wall would be a blockage for this animal because they rarely perch any higher than about 10 feet off the ground. And in some places, this bollard construction is going to be 30 feet tall. And so it will block migration of the cactus pygmy owl. And again, this is a species that exists on both sides of the wall, we have a small population remaining in the US, and there's also a small population in Sonora, and for those populations to be split, just makes it more likely that either or both of those populations will wink out. I mean, again, that's how species go extinct. You know, they become fragmented and smaller and smaller to the point where they're no longer viable.

BASCOMB: So the wall will be impassable for some wildlife but Randy says, not necessarily so for the people it’s supposed to stop.

SERRAGLIO: There was a school group down here looking at the border a few years ago, and these two high school girls, they're like 16, 17 years old, they climb to the top of the border wall, free climbing in about 17 seconds. I mean, you know, it's not gonna really slow people down very much.

BASCOMB: The top of the wall was recently strung with spools of sharp razor wire, on the US side.

Construction on the US side of the border can be disturbing for wildlife. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

SERRAGLIO: They could put it on the other side, because actually, there's another 10 feet there of US property. It's on this side so people can see it. It's for show, this is for people to see to make it look like the military is doing something and be afraid. And it's this Mexican invasion, and oh, my God, we all have to be so scared and spend billions of dollars on this ridiculous monstrosity, you know?

BASCOMB: So if you are somebody trying to get over this wall it would make a heck of a lot more sense to put the razor wire on the wall on the side that you're scaling, not the side that you're jumping off from. Because I mean, if you really wanted to, you could, you could jump out over this and land right here.

SERRAGLIO: Yeah, you could you probably a little banged up. But you could do that easily, relatively easily. You might sprain your ankle, and a lot of people do. But you know, it's a it's just the whole thing is just for show.

BASCOMB: That sentiment is echoed by Congressman Raul Grijalva, who represents Arizona’s 3rd District, including a 300 mile long stretch along the US Mexico border.

GRIJALVA: The effect is going to be minimal, in terms of unauthorized people coming or going. The wall is not the deterrent that Trump wants it to be.

BASCOMB: Mr. Grijalva is chair of the House Natural Resources Committee. Nearly 60 percent of his state is public land and because of that, Mr. Grijalva says Arizona has been targeted for more border wall construction.

GRIJALVA: I think he put Arizona's public lands at crosshairs. And the reason the public lands are so susceptible, is because they're public. They don't get hung up like they are in Texas or the issue of eminent domain and takings.

BASCOMB: Mr. Grijalva says those large tracks of public lands are often critical habitat for wildlife and a source of revenue for Arizona. And a border wall puts both in jeopardy.

GRIJALVA: It's going to rip through two wildlife refuges, wilderness areas, a very fragile desert river and two units of the National Park Service Organ Pipe, and the Coronado National Memorial, both those brought in about 260,000 people and about 30 million to these local economies in terms of revenue and tax, and spending in the area. So one has to wonder what is the purpose? It's been part of a campaign strategy that everybody in the Borderlands is going to have to pay for, and suspending and waving laws is a dangerous precedent for the rest of the country.

The Mexico side of the border wall is lush and green, habitat for numerous species of birds, mammals, and reptiles. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: The Trump administration invoked the REAL ID act of 2005 to suspend dozens of environmental laws in the borderlands including the Endangered Species Act, the National Environmental Policy Act and the Clean Water Act. Under normal circumstances, those laws could be grounds to sue the government and suspend construction projects. But the dozens of laws routinely cited to protect the environment and wildlife do not apply in the borderlands.

GRIJALVA: And that's what I think bothers us the most than anything else, the rationale for it doesn't fit the price tag cannot justify the kinds of violation, suspending of laws and more importantly, the long term harm that it does to the environment.

BASCOMB: Paul Enriquez is the acquisition, real estate, and environmental director in the border wall program management office for the US Border Patrol. He says it’s necessary to waive those environmental laws so the Border Patrol can meet their deadlines for wall construction.

ENRIQUEZ: Getting the barrier up and making sure that the Border Patrol has resources, the tools they need to secure the border is what's the priority and why the expeditious construction is needed.

BASCOMB: But Paul says they still do what they can to work within the existing environmental laws even though they are not required to do so.

ENRIQUEZ: The goal is not to just disregard the environmental laws that are waived, the goal is to ensure where we're following the intent as closely as possible of those laws, working with the resource agencies that generally have the responsibility for executing those laws, like Fish and Wildlife Service.

[DRIVING SOUNDS]

Sections of the US side of the border wall are construction zones, full of heavy machinery and equipment that disturbs animals in the area. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Back at the border Randy Seraglio stops his truck at a scenic vista near the Coronado National Monument and looks across the rugged hills towards Mexico.

SERRAGLIO: Now you're looking at the world the way a Jaguar sees it. He stands up here and he sees that mountain range over there. And he says, Yeah, I could get there tonight. And see that one over there farther away. I could be there by tomorrow night.

BASCOMB: But, of course, only if there’s not a wall blocking the way. The Customs and Border Patrol recently received 1.375 billion dollars for new wall construction in the Borderlands, including right here in the Coronado National Memorial.

[MUSIC: Glen Velez, “Pan Eros” on Pan Eros, CMP Records]

Southern Arizona, the way a jaguar sees it. The rocky landscape is a critical migratory corridor for animals in the Southwest. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

Links

Center for Biological Diversity

Center for Biological Diversity on El Jefe

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth