Portrait of a Shrinking Town

Air Date: Week of February 6, 2004

In the mid-1800’s, the business of timber turned a little red house into a bustling river town. More than 1,000 residents lived and worked on the land until the lumber ran out. Now Red House, New York is the smallest town in the state and, according to a deal made more than 30 years ago with the state park there, what remains of the town will eventually go back to the forest. Living on Earth’s Jennifer Chu visited with the some of the long-time residents who are keeping Red House history alive.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood and coming up -- the songs of winter.

But first, just northwest of the New York-Pennsylvania border lies a town in the midst of a forest. It’s just three miles from the Southern Tier Expressway, but it might as well be three thousand. Because when you get off exit 20 and drive the gravel road to the town of Red House, you leave the rest of the world behind.

Today, only thirty-eight people live in Red House, and the number gets smaller as the years go by. Living on Earth’s Jennifer Chu visited this shrinking little town and spoke with some of the residents about a deal made thirty years ago that sealed the town’s fate.

[GUITAR STRUMMING]

FRANCE: [SINGING] Left the [inaudible] at Red House, on the river oh so fine, climbed the hills of bay state, my that was quite a climb…

CHU: Lewellyn France sits in his favorite armchair, with his dog Moose at his feet. He’s singing a song about the history of his town -- a town that grew up around a river, a railroad, and a little red house, more than 150 years ago.

FRANCE: [SINGING] It’s the story of a loggin’ railroad, called the Allegany & Kinzua…

CHU: Back in the mid-1800s, rafters would guide their boats down the river, carrying lumber from the forest to the timber mills downstream. Where the river met a small brook, they would stop at a little red house on the riverbank for some food and gossip. As the timber industry flourished, so did the population of the land. A railroad replaced the rafters, and the little red house lent its name to a bustling timber town.

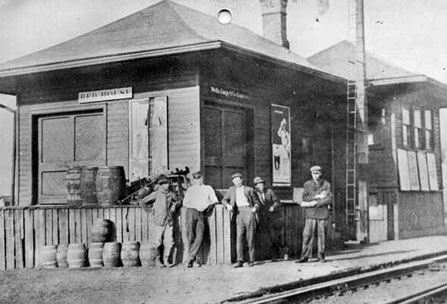

![]() Undated photograph of the Erie Railroad station in Red House. (Photo courtesy of the Salamanca Rail Museum)

Undated photograph of the Erie Railroad station in Red House. (Photo courtesy of the Salamanca Rail Museum)

FRANCE: Oh yeah, it was a busy place. It was really a booming place. I think my grandfather said there was five hotels at Red House Corners down here.

CHU: Lewellyn, or Hook, as his friends and family like to call him, is the highway superintendent and unofficial town historian of Red House, New York. He was born and raised in a farmhouse down the road. Hook is 72 years old, and is the third generation of Frances to live on Red House land.

|

|||||||||

|

CHU: The elder France, Abe, made a living cutting and hauling timber. That was back in the 1880s, when there were more than one thousand residents living and working in the town. Within 20 years, the timber ran out, and the lumber mills moved away. Now, 38 people live along the one remaining road in Red House. [SOUND OF TRUCK GEARS SWITCHED INTO PARK, DOOR CLOSING] FRANCE: It’s kind of a working truck, if you don’t mind. [TRUCK STARTING] CHU: As highway superintendent, Hook is in charge of plowing Bay State Road. FRANCE [IN TRUCK]: Yeah, so this is about all the road we do. CHU: On drives like these, it’s not the trees and the open fields he sees, but the ghosts of old houses and friends. FRANCE: I remember this was the old Kilburn house. This was where the schoolhouse was, right in here, that was it. There used to be a house up on the hill, I remember the old guy Jim Bell lived in it. I was just a little kid and his wife, Mirandee her name was, was crazy, and Jim would be out in the barn and she’d holler and scream, you could hear, “the house is on fire.” And he’d run as fast as he could and she’d be sittin’ at the table laughing. CHU: All these places now live only in Hook’s memory. The schoolhouse, the town church, and much of his neighbors’ land have been taken up by the Allegany State Park, which was set up in 1921. It started out as a 7,000-acre parcel. A few years later, the state drew a line around 67,000 acres and declared that this land would eventually go to the park. With each year, the park took up more of the land, and in the 1970s, it decided it wanted Red House, too. FRANCE: So, we all got letters. I think it was in the fall I got the letter, and it said you got 30 days to get out and it won’t bother you, or something like that, you know, and we’re gonna take the places. CHU: It turned out the state had given the park $12 million dollars to expand its boundaries. The park declared eminent domain, and gave residents 90 days to hand over their land – all 450 acres of it. But Hook and his neighbors would not let go without a fight. FRANCE: You know, my kids were here, my family, and it just meant a lot to me just to fight, I guess [laughs]. And it must’ve meant the same to everybody up in the valley, ‘cause they all did, every one of them stood up and fought for it. CHU: The people of Red House tried to broker a deal with the park. FRANCE: And then one day they called me over to the building and said we got a deal that we’d like to propose to you. We’ll buy your vacant land and leave you four or five acres around your house, and so that was the way it ended up. CHU: It’s been more than 30 years since the deal was made. Today, the park is around 2,000 acres shy of filling its boundaries. State officials say the park is no longer putting the same kind of pressure on residents to move out. But for Hook and the few residents who are left, it’s understood that the town will eventually go to the forest. He says that, in a way, it’s a good thing that the park is there because people always have a willing buyer for their land. But it doesn’t make it any easier signing it away. [SOUNDS OF TRUCK STOPPING, KEYS TAKEN OUT OF IGNITION, RUSH OF WIND] CHU: Hook pulls his truck over and parks under a stand of hemlock trees. Nearby, an old wooden fence leans into the heavy wind. Other than that, there’s not much around except dried weeds and brush. FRANCE: This is the old homestead where I lived right up until I got married. My mom and dad lived here, and then mom died, and dad died in ’85. Then my brother and I sold the place to the park, then afterwards kicked ourselves. So the park bulldozed it down maybe two years ago. It’s like that hill up there. That was all bare at one time and now look at it, it’s all woods. That’s what happens, they just buy it and it grows up to nothing. [SOUND OF FRENCH GETTING BACK IN HIS TRUCK, SLAM OF DOOR] CHU: Residents like Hook feel resigned to sell their family land, either for the money or because there’s no one left to leave it to. But others just can’t let go -- even if what they’re holding on to is an empty house. J. FRANCE: [CRUNCH OF SNOW UNDERFOOT] We’ve got snow on our feet… CHU: Jane France lives down the road from Hook’s place. She’s the town clerk and tax collector, and third cousin to Hook France. She and her husband own two properties: their own six-acre spread, and next door, an old white farmhouse that belonged to her mother-in-law who passed away a couple years ago. J. FRANCE: She always had eight or ten hummingbird feeders up, and she’d have 80 hummingbirds around at a time. It was wonderful. CHU: Do you ever go into the house? J. FRANCE: Oh yeah. It’s just empty, we’ve sold all her things. It’s just a shell, nobody’s there. CHU: It’s up to Jane’s husband, Red France, to decide the fate of his mother’s house. Right now, he doesn’t want to sell. Like Hook, Red’s grandfather built the house himself, and kept it in the family for three generations. J. FRANCE: We raised seven kids here, and they’ve all gone on to other places because there was really no future here for them. And there will be no growth. CHU: Jane says with her children gone, and having less and less money to maintain the house, it’s only a matter of time before her husband’s childhood home becomes park property. J. FRANCE: I guess I’m the most negative person around [laughs] because other people seem to think that it will go on, and I don’t know how. CHU: She says the town has changed a lot since she and her husband first moved in. J. FRANCE: Years ago there used to be some really hot and heavy contests over who was going to be supervisor or highway superintendent. Not like you would picture a campaign, but there was a little door to door neighbor kind of things [laughs]. CHU: These days, Bay State Road is no longer a campaign trail. Red House has just enough residents to fill the posts, and, for years, candidates for town council have run unopposed. SIPKO: I’m the town supervisor. I was the only one who would do it [laughs]. CHU: Melissa Sipko has been a Red House resident since 1995. She handles Red House affairs from the town hall – a small garage and even smaller office space that serves as courthouse, highway department and church on Sundays. Melissa and her husband, who works for the park, are the new generation of Red House – young families who move to the area to work for the park, stay for several years, and then pick up and move on.

|