Mister Chairman

Air Date: Week of May 7, 2004

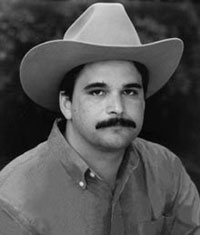

The Endangered Species Act is thirty years old and the Chairman of the House Resources Committee, Congressman Richard Pombo, a rancher from California, wants to make changes that he says will make the act more effective. He explains how it will all work to host Bruce Gellerman.

Transcript

GELLERMAN: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Bruce Gellerman, sitting in for Steve Curwood.

Thirty years ago, President Richard Nixon signed the Endangered Species Act into law. Considered by some a legal Noah’s Ark, the law was supposed to save threatened plants and animals from extinction by preserving their habitats. But now environmentalists say the Endangered Species Act itself is endangered.

Recently the House Resources Committee held the first of several rounds of hearings on proposed changes to the landmark law. Joining me from Washington is Congressman Richard Pombo, a six-term Republican from California who’s the chairman of the Resources Committee. And Mr. Congressman, thank you very much.

POMBO: It’s great to be on, thank you.

GELLERMAN: So why the hearings?

|

|

POMBO: Well, what we’re doing is taking a serious look at a law that is 30 years old, and trying to find out what we can do to improve upon the effectiveness of the law. GELLERMAN: But as Ronald Reagan said, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. POMBO: Well, but it is broken, and that’s a big part of the problem. You know, over the years we’ve had over 1,300 species that have been listed. Twelve of those have been recovered or taken off the list. And that is not a good record in terms of the billions of dollars that have been spent both in public money and private money. I happen to believe there has to be a better way of recovering species, and doing a better job of what the intentions of the Act were, than what we’re currently doing. GELLERMAN: But environmentalists say that the law is a safety net, and it’s not realistic to expect a species near extinction to recover quickly -- or sometimes not at all. POMBO: It is a safety net, but at the same time, we are spending millions of dollars of public money – billions of dollars in total, in public and private money – and we’re not effectively bringing these species back from the brink, so to speak. What we have is a law that is based on 30-year-old technology, 30-year-old ideas, and I think we need to look at what has worked and what’s not working. GELLERMAN: So what would you like to change? POMBO: Well, one of the things that we are – in fact, it’s what we had the hearing on last week, is having the ability to, as a part of the critical habitat process, also adopt the recovery plan. So that in effect what we’re doing is, we have the science that’s being done to determine how you’re going to recover this species, and at the same time, you’re designating what the critical habitat is necessary to recover that species. Those should be done together. Currently, in the law they’re done completely separately. GELLERMAN: My understanding is that you want to make it more difficult to preserve critical habitat. POMBO: Well, that’s not true. That is not what we’re doing. What we’re doing is we’re trying to set aside the habitat that is necessary to recover the species. What they do now is they adopt critical habitat based upon very limited knowledge, or limited scientific information, as to how they could go about recovering that species. It’s backwards the way the law is currently being implemented. They should know what it’s going to take to recover the species or maintain its numbers before they go out and designate critical habitat. GELLERMAN: Well, according to a position paper you issued before the hearings, you called this provision of the law about critical habitat “perverse.” POMBO: And it is, because it’s backwards. Before they’ve even done the science to determine how they go about doing a recovery plan, they are required to go in and designate critical habitat when they really don’t have the information to do it. GELLERMAN: So what you want to do, if I get this correctly, is that you want the land deemed absolutely essential and indispensable to save the species. And only then would it become critical habitat. POMBO: And that is part of determining what a recovery plan is, and what a process they would go through in terms of recovering the species. GELLERMAN: But isn’t that a high barrier? POMBO: I don’t believe so. I believe it’s what we should be doing in terms of what habitat is necessary to recover the species. Right now, they declare habitat where the species may or may not be, that may not be necessary for a recovery plan. Or they may miss land that should be included as part of the critical habitat, just for the simple fact that they don’t know. GELLERMAN: But aren’t we gambling? I mean, extinction is forever. And if this doesn’t work, if your plan wouldn’t work, we stand to lose hundreds and hundreds of plants and animals. POMBO: Well, I would contend that what we are proposing, and what the proposed bill would do, would actually do a better job of recovering species than what we’re currently doing. GELLERMAN: Um-hmm, because I was reading something from the Defenders of Wildlife. We called them up, we spoke to Jaime Rappaport Clark of the organization, and she says, speaking about you, “yet this chairman is single-handedly leading a crusade to eviscerate the habitat protection standards of the Endangered Species Act.” POMBO: I’m glad that you talked to Ms. Clarke, because as the director of Fish & Wildlife Service in the Clinton Administration she advocated that we fix the critical habitat plan. And in fact, when she was the director of Fish & Wildlife Service, she said that she had seen no positive benefit to any species of declaring critical habitat. Now that she has a different job she’s saying a little bit different things. But as the director of Fish & Wildlife in the Clinton Administration her position was that it did little if no good to recovering species the way the law currently works. GELLERMAN: Well the law doesn’t seem to work all that well if you consider how long it takes for some animals to actually make it on to the list. Some animals spend twenty, even 30 years, just waiting to get listed. POMBO: And some of those species should not be listed. Just because a species is on the candidate list does not mean that it is endangered. GELLERMAN: Do you consider yourself an environmentalist? POMBO: Sure I do. I mean, who is not an environmentalist? Who doesn’t care about the natural environment around them? I mean, find someone who doesn’t want clean water or clean air. Find somebody who doesn’t care if species become extinct. That is a moral value that we as Americans share. But the problem we run into is that people invest so much into a law they lose sight of the fact that the law is not working. And there’s gotta be a better way to do this than what we’re currently doing. GELLERMAN: Because you know what your critics say. They say, you know, here’s a guy who runs a ranch in California, and he’s more interested in the property rights and compensating landowners than he is about protecting endangered wildlife. POMBO: Well, as a rancher and somebody who grew up on the farm and spent all my time in and around wildlife and with animals, I care very deeply about it. But I also do care very deeply about people’s private property rights and the individual rights we as all Americans have. It’s no different than any other civil right that is protected. I happen to believe that we can protect endangered species, that we can have a clean environment, that these people that are out there saying we have to choose between having a healthy economy and a healthy environment are presenting a false choice. I think we can do both, we just have to be willing to do it. Unfortunately some of these folks are more interested in maintaining the status quo, even though it’s proven to be a failure, than they are in looking at what we can do to make it better. GELLERMAN: But in striking this balance, where do you come on the side of property rights versus preserving species? POMBO: I don’t think you have to make that choice. I think you can do both. Part of that is by changing the incentives that exist in current law. Right now it is seen as a big disincentive if a property owner finds endangered species on their property. We can change that and make it a positive – through grants, through programs that are run through the federal and state government, so it becomes a positive incentive for people to have endangered species and to manage their property in a way that creates and maintains habitat. GELLERMAN: At one point a few years ago, you wanted to pay landowners to preserve their habitats. POMBO: And I think we should. And I think that would completely change the negative incentives that exist in the law right now. By having a cooperative plan between private landowners and the government, in terms of protecting endangered species habitat, would completely change the incentives that exist right now in current law. GELLERMAN: It would be tough to pass any changes to the Endangered Species Act this year – it’s an election year. POMBO: Oh, absolutely. This year is going to be tough to – it’s going to be tough to pass anything. But I do want to start people talking about it and thinking about it. I do believe there are responsible people within the environmental community who will come to the table and say, you know, there are problems with the current law, these are the things that we think need to be fixed. GELLERMEN: Congressman Pombo, I know that before you became a lawmaker you were a full-time rancher. And you got into politics kind of in a strange way. I guess there was a case of endangered species on your land? POMBO: Well, most of my district is considered habitat for one endangered species or another. In the area in which I live in California we have an endangered fox. It’s a kit fox in our area. And that has had an impact on decisions that are being made out in that part of California. GELLERMAN: You’ve had an interesting political career, Congressman. You’re sitting as the chairman on this committee and you, I understand, bypassed nine other more senior Republicans? POMBO: Yeah, I did. And it was – when there was an opening in the chairmanship of the committee I decided that I would make a play to become next chairman of the committee. And I was successful in doing that. GELLERMAN: How’d you do it? POMBO: Well, I think a lot of it was just convincing my colleagues that I could do the job, that I could hopefully change what some of these old debates are. It’s like what we’re talking about today. A lot of these old debates are people that rush to opposite ends of the political spectrum and start throwing rocks at each other. I believe there’s a better way to do this. I believe that there are ways for us to sit down and talk about these issues and figure out a better way to do it. Not everybody is going to get everything they want, but in the end I think we can come to a compromise that will do a better job than what we currently do. And there are a lot of issues like this that are out there that I think we just need to put down our swords for a little while and actually sit down and talk to each other. GELLERMAN: Congressman Pombo, thank you very much. POMBO: Well, thank you. I’ve enjoyed having the opportunity to talk to you. GELLERMAN: Richard Pombo is a Republican from California and chairman of the House Resources Committee. [MUSIC BREAK] GELLERMAN: Coming up on the menu: Healthy fish and sustainable seafood. Stay tuned to NPR’s Living on Earth. Links

|