Cotopaxi Pilgrimage

Air Date: Week of December 17, 2004

Until recently many Ecuadoran Tigua Indians had never visited the mountain that rises so often from their paintings—the volcano Cotopaxi. When the government of Ecuador began charging admission, they stopped going. But recently the sons of Ecuador’s most famous Tigua painter climbed their sacred source of inspiration for the first time with producer Nancy Hand.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. During the past 30 years, Ecuador has become known for meticulously detailed paintings on sheepskin. The painters are Tigua Indians and their work depicts life in the Andes Mountains, of which a recurring image is the nearly perfect snow-capped cone of their sacred mountain, Cotopaxi—the highest active volcano in the world. No Tigua has set foot on Cotopaxi for three decades since it became a national park and started charging admission. Recently, some Tigua painters decided it was time to go back. And producer Nancy Hand accompanied them as part of the “Worlds of Difference” series.

[DRUM AND FLUTE MUSIC IN GALLERY]

HAND: In the village of Tigua, in the folds of Ecuador’s highland moors, Julio Toaquiza and his son, Alfonso, stand in a long room, serenading visitors with a wooden flute and sheepskin drum.

|

HAND: The walls surrounding them are hung with dozens of brightly colored paintings. They show hills quilted with fields of potatoes, beans and barley, and condors circling over grazing sheep and llamas. Within this painted landscape hovers the great white cone of their holy mountain, Cotopaxi. TOAQUIZA: (VOICE OF TRANSLATOR) My name is Julio Toaquiza. I learned to paint from a dream. HAND: Julio Toaquiza was the first Tigua painter. Now 57 years old, he stands barely five feet tall, his skin weathered by cold and wind. Julio married at 14 and had 12 children. Then one day a shaman told him he would have an important dream. TOAQUIZA: Don’t let it go to waste, he said. And I thought to myself, I have no schooling or anything, what work is there for me? What dream am I going to have? HAND: But one night, Julio did have a dream. His wife was spinning yarn and he was painting her image on sheepskin. TOAQUIZA: I didn’t know what to paint with. I went to buy dye, like the kind we use for ponchos. I brought green, purple, black and red. HAND: He began painting his people who had worked this land since long before it became a country named for the equator it straddles. TOAQUIZA: That’s how I learned. And I have taught all my children. Before they were in school, they were already helping me fill in colors. [FLUTE SOUND] HAND: Thirty years later, most of the 1,500 Tigua partly support themselves by painting. Their works have been shown in Washington and Paris. Visitors make the three-hour trip from Ecuador’s capital, Quito, to Julio’s one-room, dirt-floored house to meet the father of Tigua art. [FOOTSTEPS ON TILE IN GALLERY] TOAQUIZA: This is my painting. This is Cotopaxi. Our grandfathers worshipped it. HAND: As a young man, Julio Toaquiza climbed the 19,000-foot volcano for sacred ceremonies. But in this painting, the climbers are white-skinned. They carry cameras.

HAND: The only Tigua people in this painting are far below, selling other paintings of Cotopaxi to tourists. Since Ecuador’s government made the volcano a national park and began charging admission, Tigua don’t go there. TOAQUIZA: Now you have to pay to get in. Why don’t they let our people go and see it, like our schoolchildren? HAND: But now Julio’s son, Alfonso, has decided the time has come to go to the mountain. His father is too old and ill, so Alfonso has gathered some of his brothers and cousins – all painters – with their families to visit Cotopaxi for the first time. [MOTOR STARTING. VOICES, VAN NOISE] ALFONSO: My name is Alfonso Toaquiza. I am the third son of Julio Toaquiza. EDGAR: My name is Edgar Toaquiza. HAND: What’s your name? ALEX: Alex. ALFREDO: (VOICE OF TRANSLATOR) My name is Alfredo Toaquiza. I’ve been painting since I was eight years old.

|

Julio Toaquiza and his family. (Photo: Alan Weisman)

Julio Toaquiza and his family. (Photo: Alan Weisman)

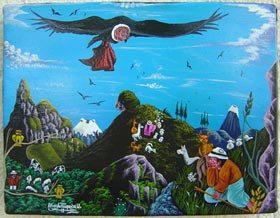

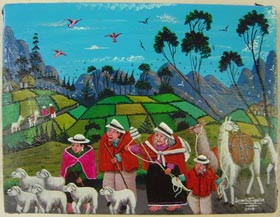

Top: Painting by Alfredo Toaquiz Bottom: Painting by Luzmilla (Photos: Alan Weisman)

Top: Painting by Alfredo Toaquiz Bottom: Painting by Luzmilla (Photos: Alan Weisman)  Painting by Alfredo Toaquiz (Photo: Alan Weisman)

Painting by Alfredo Toaquiz (Photo: Alan Weisman)  Alfredo Toaquiza at Cotopaxi (Photo: Alan Weisman)

Alfredo Toaquiza at Cotopaxi (Photo: Alan Weisman)