Sacred Sea

Air Date: Week of September 14, 2007

Lake Baikal, the deepest, oldest, and largest supply of fresh water in the world, holds powerful sway over the hearts and minds of Russians. It also drew former Living on Earth Senior Editor, Peter Thomson, on a journey around the world to visit its majestic shores. He’s written about his experience there in his new book, “Sacred Sea: A Journey to Lake Baikal” and joins host Steve Curwood to talk about it.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Lake Baikal, in the middle of Siberia, is no ordinary lake. One hundred eighty six miles long, one mile deep, and 25 million years old, Baikal is the oldest, deepest lake and holds more fresh water than any other lake in the world.

For Peter Thomson, a freelance journalist and former Living on Earth senior editor, Lake Baikal also holds countless stories waiting to be told. To get there, Peter and his brother, James, traveled across the Pacific Ocean by freighter to Siberia.

He writes about their adventure in his new book, “Sacred Sea, a Journey to Lake Baikal.” Peter, tell me about this amazing place—what does it look like?

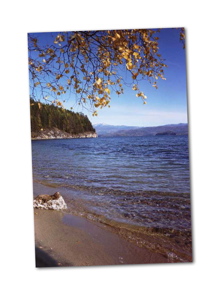

Lake Baikal. (Photo: Peter Thomson)

CURWOOD: So, you go halfway around the world to this place. And you’re standing-- your first day-- on the shore of Lake Baikal. The van that’s taken you from the train station has broken down and there you are getting your first up-close look and touch of this place. I mean, was it everything you expected?

THOMSON: Well, it was and it wasn’t and it was a very weird experience, which I try to describe in the book although I’m not sure that I really captured it. We had been traveling through Russia for a week at that point and we were tired, we were a little bit sick, we were incredibly disoriented—my brother and I—and in a way it was this very anticlimactic experience. You know, you’ve traveled halfway around the world to this place that you have revered and that everyone who knows about it says, ‘Oh my God, I’ve got to get there!’ And you get there and you’re just sort of tumbled out onto the beach and all of a sudden there’s this water. And you go up and you look at it and you touch it and—it’s just water.

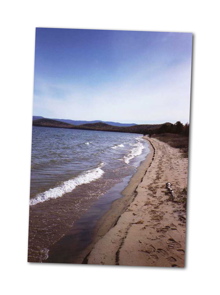

Baikal Beach. (Photo: James Thomson)

CURWOOD: You sure it wasn’t that Russian vodka?

THOMSON: Uh, actually, now that you mention it.

CURWOOD: What makes Lake Baikal so special? What makes it ecologically unique?

THOMSON: Well, it’s incredibly pure. And that’s a result both of sort of geologic processes and biologic processes and I think most people think of purity as something that’s, you know, a result of human processes but actually in Baikal it’s what scientists call oligotrophic, which means it has almost no nutrients or minerals in it.

Lake Baikal. (Courtesy of the Image Science and Analysis Laboratory, NASA Johnson Space Center (http://eol.jsc.nasa.gov))

And at the top of the food chain you have the world’s only unique species of freshwater seal. There is no other freshwater seal anywhere in the world than the Baikal seal, which is called the ‘nerpa’ locally. And it somehow made it’s way upriver from the Artic Ocean—2,000 miles of river—to this lake.

Baikal Silhouette. (Photo: Peter Thomson)

THOMSON: Well, it’s almost difficult to imagine—living in the United States. You know, we have a number of incredibly beautiful, revered places like Yosemite Valley and the Grand Canyon, which we think of as sort of these pinnacles of wonder in the natural world. But if you could somehow add a layer of religious fervor and deep nationalism to your engagement with those places you might have an idea of what it’s like to be a Russian imagining Lake Baikal.

Millions of Russians feel they need to have a pilgrimage to Baikal in their lifetime sometime. Almost like Muslims wanting to go to Mecca for the Hajj or Christians or Jews wanting to go to Jerusalem.

And most of those people don’t make it there but on my way into the lake, I was riding in on the train and I spent most of my time looking out the windows and I was usually the only person in the hallway but all of a sudden I see a glint of blue out the window and the hall fills with people and they are singing. And they are toasting with vodka and tea. And I don’t know Russian but what I could understand was Baikal. They were singing this ode to their lake and it was an incredibly powerful and moving experience to witness that, and it gave me a sense that this was a place which was unlike anything that I’d ever experienced before in terms of their relationship to it.

CURWOOD: So, Lake Baikal is this amazingly pure, intact ecosystem but it faces an awful lot of challenges, you found.

THOMSON: Yeah, well, I mean I went in I think somewhat eyes wide open. You know, I knew that it was probably as close to intact as you can get for a large body of water like this but also that there were definite threats to it.

Chivyrkuysky Gulf, Lake Baikal. (Photo: Peter Thomson)

On the other hand, there’s a lot of industry and cities upstream in Mongolia and Eastern Siberia that flow by river into the lake so there is real impact on the lake. And then there are a couple of paper mills-- one in particular that’s right on the lake-- that have a very strong local impact and traces of this pollution are found throughout the food chain, throughout the water, from top to bottom of the lake. So there are some real concerns there, to be sure.

CURWOOD: By writing this book, of course, somebody a hundred years from today can take a look at it. What do you think will have changed in Lake Baikal from today to say, a hundred years from now? And why would someone perhaps be grateful for the record you’ve created, based on today?

Chivyrkuysky Gulf, Lake Baikal. (Photo: Peter Thomson)

I’m not certain that that will happen but I sure hope so because it’s entirely possible that we can do that. We know enough not to make the same mistakes there that we’ve made elsewhere, to pull back from the industrial impacts in the region, to build an economy there that is based on an intact ecosystem rather than at the expense of the ecosystem, through clean, low-impact industry, through a recreational economy, really, I mean it can’t be much more than that without having much of an impact.

It’s a very tough trick to turn as people are learning all around the world as they do try to develop what is called ‘ecotourism’ or ‘sustainable tourism’ but I think that Baikal is the kind of place where it’s still possible to do the right thing by nature and by the people who live there and there have been people there for thousands of years. So I hope in a hundred years that that will be what people remember and that this book somehow played a role in making that possible.

CURWOOD: Peter Thomson’s book is called “Sacred Sea: A Journey to Lake Baikal.” Thank you so much, Peter.

THOMSON: Thanks, Steve.

CURWOOD: To see photos of Lake Baikal and hear Peter reading from his book, go to our website, loe.org.

Photo: (16-1 Baikalsk Pulp and Paper Mill)

Caption: Baikalsk Pulp and Paper Mill. (Photo: Peter Thomson)

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth