Dispersant Discussion

Air Date: Week of July 23, 2010

A plane sprays dispersants over the leaking oil in the Gulf of Mexico. (NWFBlogs)

Nearly 2 million gallons of chemical dispersants have been applied to the Gulf of Mexico in the wake of the BP oil leak. Host Jeff Young reports that many of the country's leading marine scientists have signed a consensus statement against the use of dispersants on that scale.

Transcript

YOUNG: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios in Somerville MA this is Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young. Well, since late April some 1.8 million gallons of chemical dispersants were sprayed on the Gulf of Mexico’s oiled surface or injected deep into the plume escaping BP’s Macondo well.

Now toxicologists and marine scientists are calling for an end to wide use of chemical dispersants and the start of more focused research into the harm dispersants may have caused.

SHAW: It’s a controversial thing, the use of dispersants, because the ecosystem down there is so toxic this will be a legacy for decades to come. Not months, not years… decades.

Marine toxicologist Susan Shaw authored the consensus statement opposing the use of chemical dispersants in the Gulf of Mexico.

SHIPP: I think almost all of us in the marine science area who study the ecosystem are in agreement that the use of dispersants is a terrible choice.

YOUNG: That was Marine Sciences Professor Bob Shipp, and toxicologist Susan Shaw. They’re among scientists circulating a petition opposing chemical dispersants. Oceanographer Sylvia Earle was the first to sign on.

Earle is a pioneering figure in ocean science. She’s explorer-in-residence at National Geographic, and in the early 90’s she was chief scientist for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. NOAA is one of the federal agencies that allowed the broad use of dispersants in the Gulf crisis. Sylvia Earle says that was a mistake.

EARLE: The role of dispersants is exactly what the name suggests: that is to break the oil up into small pieces and spread it widely. When applied at the surface, it means that the oil sinks, it is no longer a problem for those who are trying to clean up the oil, becomes a problem, though, for the oceans…looks as though it’s gone- it’s not gone- it just becomes a part of the ocean system.

A black tip shark swims through oil in the Gulf of Mexico. (NWFBlogs)

The real goal should be to get the oil out of ocean rather than to keep it in the ocean. And, the second thing is, in small pieces it becomes available and touches many more creatures in the water column than it does if it’s just floating on the surface.

YOUNG: Sylvia Earle’s name adds some heft to the scientists’ petition. It was written by Susan Shaw, a toxicologist who directs the Marine Environment Research Institute in Maine. Shaw dove into this issue—literally. She swam in the Gulf’s dispersed oil to gather samples. She found the combination of dispersant and oil is more toxic than either material alone.

SHAW: The dispersant acts like a delivery system for oil in the water. And oil contains hundreds of compounds that are toxic to every organ in the body and many are carcinogens. So if you have the dispersants making that oil more easily moving into cells and organs of the body, you have a much more toxic oil than just crude oil alone.

A plane sprays dispersants over the leaking oil in the Gulf of Mexico. (NWFBlogs)

YOUNG: Other scientists are documenting the early effects of that combination Shaw describes. Marine Sciences professor Bob Shipp of the University of South Alabama is measuring the organisms at the base of the Gulf’s food chain.

SHIPP: Take for example, an anchovy. An anchovy swims through the water with its mouth open, filtering food with its gill filaments. If it has to swim through a mass of water that has oil in it, those oil droplets will collect on the gill filaments and the anchovy will die. Now the anchovy, as well as many other species, is the major link between plankton and the higher members in the food web.

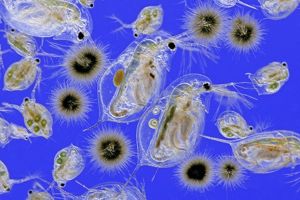

The same thing happens with the plankton, many of the little plankton organisms, almost microscopic, filter feed. And when they filter the oil it’s going to kill them. So most of us feel like using dispersants and putting oil in the water column is absolutely the worse thing that could happen.

Plankton are the tiny microscopic organisms that make up the base of the ocean food web. Scientists are concerned that these filter feeders are eating oil and will bioaccumulate in higher sea life. (Wellcome Images)

YOUNG: Bob Shipp at the University of South Alabama. The main dispersant used, COREXIT, is made by the Illinois-based company Nalco. Nalco spokesperson Mike Bushman says Corexit has approval from the Environmental Protection Agency.

BUSHMAN: Our product is safe. It biodegrades very rapidly. It does what it’s intended to do which is to break the oil into droplets where it can biodegrade more rapidly in the water column. We have provided that service and made available whatever we have been requested to provide.

YOUNG: Nalco was criticized for not providing information, especially about COREXIT ingredients. Bushman says that information is now available. But, when a Senate subcommittee asked Nalco executives to testify at a July 15th hearing on dispersants, they declined. That left government officials like EPA administrator Lisa Jackson to take the heat. Jackson told the panel that this is the most dispersants that have ever been used on a U.S. oil spill.

JACKSON: BP had gotten up to 70,000 gallons of chemicals used in one single day. That was an alarming number.

YOUNG: In late May EPA told BP to scale back its use of dispersants and to switch to products less toxic than COREXIT. But subcommittee chair, Maryland Democrat Barbara Mikulski, reminded Jackson that BP largely ignored EPA’s demand for weeks. And Senator Mikulski took Jackson to task.

MIKULSKI: Often we’re told, “Don’t worry honey. We’ll take care of you and it won’t hurt.” We only then find out that what we thought was a good product turns out to have vile consequences. I don’t want dispersants to be the agent orange of this oil spill.

JACKSON: Madame chairman we are in a situation with no perfect solution.

YOUNG: Again, EPA’s Lisa Jackson.

JACKSON: Because there are scientific unknowns we had to make decisions that are a series of trade-offs. At the time we were risking that which we’ve all seen on TV, which is large amounts of oil at the surface, which got by the skimmers and got by the burners and would end up in the marshes where they do the most damage, and in the shallows. That trade off isn’t easy.

YOUNG: Jackson says EPA continues to test the toxicity of COREXIT. Marine scientist Bob Shipp was also scheduled to testify at that Senate hearing. But he broke his foot and couldn’t travel. Had he been there, Professor Shipp might have picked a bit of a fight with Administrator Jackson. He says EPA’s testing misses the point.

Dr. Bob Shipp chair of the marine science department at the University of South Alabama. (Photo: Bob Shipp)

SHIPP: I think there is a red herring here with this talk of toxins, you know, whether the dispersants are toxic or not. They’re toxic but that’s not the main concern. The main concern is they are putting them and oil in the water column and that’s lethal to much of the life that lives there.

YOUNG: This is the major tool that BP and government agencies have been relying on.

SHIPP: Yes, [laughs] that’s right. What’s the purpose of it? It’s to hide it. Out of sight, out of mind. And it makes no sense at all. If you use dispersants on a limited spill on the surface that’s ok. But this spill is so massive that the justification, you know, that if we use dispersants it won’t get to the marshes…that’s not true. So, the use of dispersants is just totally unjustified.

YOUNG: Part of the petition Professor Shipp and other scientists are signing says, “The use of dispersants does not represent a science-based, quantifiable “tradeoff” but rather amounts to a large-scale experiment on the Gulf of Mexico. Oceanographer Sylvia Earle says the lack of solid science about dispersants should have led decision makers to be more cautious about their use.

EARLE: The precautionary principle would seem to be the wise course of action rather than, ‘let’s just do it and then see what happens.’

Dr. Sylvia Earle is a National Geographic Explorer in Residence and the 2009 TED Prize Winner. (National Geographic)

YOUNG: The Obama administration has made a strong point that it will make policy based on science. Does this seem to you like a decision based in science?

EARLE: The policies that are in effect are based on previous experience. That led those at the time to think that this was, perhaps the best course of action to protect beaches and marshes. And, from the coast’s standpoint the place where most of the people are, you have helped solve the problem.

But if you think like an ocean, which is how I tend to think, you’ve caused a greater problem. It is frustrating to see the consequences of what is happening and the inability to do what seems like the right thing to do sometimes. But perhaps the effects of what has happened now will cause a re-thinking of these policies.

YOUNG: Pretty painful way to learn a lesson.

EARLE: Very painful. But, let’s hope we do learn. The greatest tragedy would be if we have lived through this experience for the last three months and failed to change our ways as a consequence of it.

YOUNG: You can hear more of our interview with Sylvia Earle and read the scientists’ consensus statement on dispersants at our website LOE dot ORG.

Links

Click here to read the scientist’s consensus statement on the use of dispersants.

Susan Shaw is Director of the Marine Environment Research Institute

Click here to hear an extended interview with Dr. Sylvia Earle

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth