Spinach Power

Air Date: Week of September 7, 2012

(Julie Turner/Vanderbilt)

Scientists at Vanderbilt University have found an exciting new use for spinach, harnessing energy from the sun. Kane Jennings, a Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, tells host Steve Curwood that using a protein found in Spinach can create a highly productive solar cell.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Popeye claimed that spinach was the key to bulging biceps, but researchers at Vanderbilt University have just found a new use for the super-vegetable, harnessing the power of the sun.

Kane Jennings teaches Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at Vanderbilt University. With his colleague Professor David Cliffel, he has developed a new way to use proteins found in spinach to generate solar power. He joins us now from Nashville. Professor, welcome to Living on Earth.

JENNINGS: Thank you very much, I'm glad to be here.

CURWOOD: So, it sounds like Popeye was right… spinach really is strong to the finish…

JENNINGS: That’s absolutely true!

CURWOOD: Now, how do you get juice out of spinach… the electric type… what exactly have you developed here?

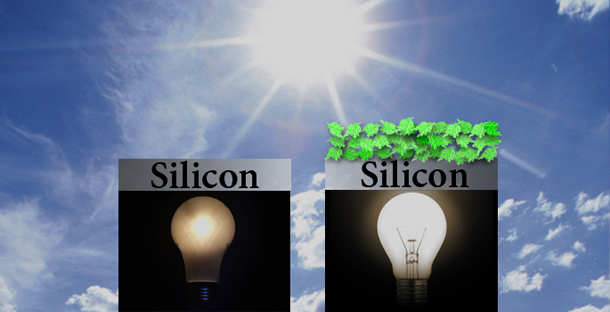

JENNINGS: What we did was extract out a key protein found in spinach and all other green plants known as photosystem 1. We placed photosystem 1 on a surface, it’s able to capture incoming light, much like it does in photosynthesis – both current and potential – to power a solar cell.

CURWOOD: What made you think, though, of using vegetables to make solar cells?

JENNINGS: Well, photosynthesis, if you look at the rate of power of all of the photosynthesis on the planet… it is eight times greater than all of the power we are developing through fossil fuels at the moment. So photosynthesis is just a giant solar conversion process out there in nature. So, therefore, we want to use green plants that are very well known for capturing the sun’s light and producing power.

CURWOOD: What makes your spinach solar cells more productive than other bio-hybrid solar cells?

JENNINGS: We have found that if we place this protein onto a positively built silicon electrode, that we get 2,500 times more power than if we placed this protein film onto a metal electrode. We’ve also found that we get six times more power out over just a silicon electrode alone.

CURWOOD: You’re saying that, by using spinach, you can have solar cells that are basically six times more powerful than what’s on some people’s roofs right now?

A team of senior undergraduates from Vanderbilt made a 2 ft by 2 ft solar panel out of spinach-based Photosystem to win three awards at the EPA's National Sustainable Design Exposition. (Vanderbilt University)

JENNINGS: Not exactly. Because, what we’re…. in that case we’re comparing apples to oranges. What’s on folk’s roofs right now would be a silcon-based photovoltaic, which is a very solid-state type device. What we’re looking at here is more of a wet-based solar cell. More like kind of a solar battery, where you’ve got small cells that act to transfer the power away from the protein film.

CURWOOD: But power-wise, how does this compare to the conventional cells that we have today?

JENNINGS: We’re not quite in the conversation at this point, with say, conventional PVs. What we have shown is that we’ve increased the power output on these simple liquid-based solar cells by a million-fold in the last five years. If we stay on this same trajectory, we’ll be very close to those more traditional photovoltaics in about three years.

CURWOOD: And spinach is cheaper than silicon?

JENNINGS: Spinach is very affordable, that’s right.

CURWOOD: Now, spinach is a very nutritious vegetable, we don’t always like to of course… what impact does that have on its uses for solar energy. I mean, might there be a tighter spinach market once this gets going?

JENNINGS: Yes, what I would really like to see long-term is if we are able to continue to make these substantial improvements in our performance, is for us to shift away from traditional food sources like spinach, and ultimately use energy sources that are non-food based. For example, we are now working on a project where we can actually extract photosystem 1 from kudzu.

CURWOOD: Ah!

JENNINGS: Now, kudzu is an invasive, rapidly growing vine that covers many millions of acres in the southeastern United States.

CURWOOD: So, Professor Jennings, how far away are we today from having commercially marketable spinach, or, say, kudzu, solar cells?

JENNINGS: I would say that we are about, in the neighborhood of five to ten years, of having commercially marketable solar cells based on bio-hybrid technology. We need to make performance improvements to get us much closer to what traditional photovoltaics are giving out right now. And we need to really investigate all of the materials issues to make sure that we’re getting the highest efficiencies we can out of these systems.

CURWOOD: Before we go, do you think SweetPea would approve?

JENNINGS: I think SweetPea would be happy to know that we are getting alternative types of power out of spinach.

CURWOOD: Kane Jennings is Professor of Chemical and Bimolecular Engineering at Vanderbilt University, thank you so much, professor.

JENNINGS: Thank you very much, I've enjoyed this.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth