Juneteenth

Air Date: Week of June 21, 2013

|

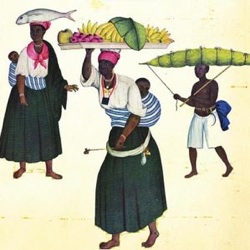

African Americans celebrate their ancestors’ emancipation from slavery on June 19th, a holiday known as Juneteenth. On that day, families gather to picnic and cook out across the South. The voyage from Africa isn’t often on people’s minds, but it is in their stomachs. Ike Sriskandarajah digs into the green foodways of the Black Atlantic.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Since 1865, many African American communities have marked and celebrated their emancipation on June 19. Juneteenth, as it’s known, is a day for picnics and cookouts in honor of the end of American slavery. But often overlooked at those gatherings is the role that Africans and the slave ships played in bringing some of those picnic foods to American tables. Today we revisit how Living on Earth's Ike Sriskandarajah explored the way culture and agriculture overlapped in that dark chapter of American history.

SRISKANDARAJAH: For 1,000 years before the Atlantic slave trade started, the origin of humanity was also its cornucopia. Many of the world’s staple foods first sprouted from African soil. They’re on your picnic table, from the sesame seeds on your bun to the Worcestershire sauce in your hamburger to your slice of watermelon. And if you reach into the cooler…

[COKE CAN OPENS]

CARNEY: The cola in cocoa cola is an African plant as well, the cola nut.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Judith Carney, is the author of In The Shadow of Slavery, Africa’s Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World. Her book traces the path of foods that traveled with slaves including an ingredient in the world’s most ubiquitous fizzy drink.

CARNEY: Cola came on slave ships - they used cola in the casks of water that were carried on the ships to refresh water that was going bad during the prolonged voyage.

SRISKANDARAJAH: So they were drinking coke 400 years ago on slave ships?

CARNEY: [LAUGHS] No, no, but, you need the coca part of it and the sugar I think. I would say it’s slightly more bitter than eating a potato raw.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Another of our favorite drinks, coffee, also comes out of Africa and millet, black-eyed peas. Judith Carney tracks the migration of these foods through historical records.

CARNEY: I went back and looked at the journals and the diaries of the ship captains and the “slavers”. How are they feeding people for six weeks to three months voyages?

SRISKANDARAJAH: One such log was written by a 17th century slave trader, moored off the coast of western Africa.

[OCEAN WAVES, SEAGULLS SQUAWKING]

MAN 1: A ship that takes in 500 slaves, must provide above a hundred thousand yams; which is very difficult, because it is hard to stow them, by reason they take up so much room; and yet no less ought to be provided, the slaves being of such constitution, that no other food will keep them; so that they sicken and die apace.

SRISKANDARAJAH: The slaver’s human cargo was valuable. So captains bought food the captured Africans could eat, and they bought enough of it. Sometimes the ships would even land in the New World with surplus.

Judith Carney is the author of “In the Shadow Of Slavery: Africa's Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World.” (University of California Press)

CARNEY: And that I argue, the unwitting conveyance of bringing African food to the Americas was the slave ship.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Once in the Americas the slaves were scattered to work on plantation cash crops. But they were also expected to feed themselves.

CARNEY: We think of plantations as places that produced export crops, but we don’t think about them as also places where human beings had to also know how to farm for their own nourishment.

SRISKANDARAJAH: A Danish Traveler, Johan L. Carstens, wrote a diary describing his observations of the Americas during the early Eighteenth Century

[FIFE MUSIC]

MAN 2: These plantation slaves received nothing from their master in the way of food or clothing except only the small plot of land at the outermost extremity of his plantation land that he assigns to each slave.

SRISKANDARAJAH: The staples from Western Africa flourished in the South, and from those meager plots came a rich food tradition. It was good enough for slaves, it was even good enough for a founding father. Culinary historian Michael Twitty says that Thomas Jefferson actually bought food from his slaves.

Michael Twitty curated the African American Heritage Seed Collection.

TWITTY: Oh yeah, oh yeah. The day to day needs of his own kitchen table, much of that was supplied by the enslaved population of Monticello. There are extensive records of purchases for the main house from the enslaved community. He would buy cabbage, watermelon, he’d buy sprouts.

SRISKANDARAJAH: President Jefferson wasn’t alone.

TWITTY: Before the new immigrants come in at the turn of the 20th century, we are the ethnic restaurateurs of America.

SRISKANDARAJAH: And Twitty says that African Americans didn’t just add ingredients to America’s Melting Pot, they spiced it up too.

TWITTY: Red pepper was the most important, ubiquitous spice.

SRISKANDARAJAH: So important, that in 1780, close to 100 slaves newly imported from West Africa, protested until plantation owner Josiah Collins supplied the spice.

TWITTY: Within a year of their arrival he has to order 1000 pepper pods to season their food because they will not eat bland food. They expressed to him that we want the pepper pods!

SRISKANDARAJAH: Hot sauce has been on most southern tables since. African American cuisine still has its roots in those peripheral plots but, but African Americans’ connection to the land has changed.

TWITTY: We were an agrarian people for millennia even through the period of slavery. We went from being 90 percent agrarian to 90 percent urban in less than a 100 years think about that.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Freedom wasn’t free, emancipation cost the slaves their link to the land. African Americans couldn’t own or lease land - their only option was punitive sharecropping.

TWITTY: All that oppression hurt us in the long run because it divorced us from the land, it divorced us from nature and through food we can reconnect with that and begin to repair that link.

SRISKANDARAJAH: That’s part of Michael Twitty’s mission, he works to bridge that gap. He’s put together the African American Heritage Seed Collection. It offers heirloom seeds to today’s gardeners.

TWITTY: To see an okra plant that you know was growing in gardens of Mt. Vernon or Monticello, to see a kind of rice that was grown in 17th century South Carolina. It gives you the sense of such connection. Because I always tell people my own little corny saying, growing history is knowing history.

SRISKANDARAJAH: And knowing history can turn your bowl of gumbo into a portal back through time. I’m Ike Sriskandarajah. Happy Juneteenth.

Links

Check out Michael Twitty's seed collection from the Landreth Company

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth