Citizens on the Watch for Hummingbirds

Air Date: Week of July 26, 2013

Calliope hummingbirds are the smallest birds in North America (Photo: Dan Tracy for Hummingbirds at Home).

Hummingbirds are particularly susceptible to the changing climate because of their speedy metabolism and lengthy migrations. They need a reliable nectar source, but some flowers now blossom earlier. National Audubon Society scientist Geoff LeBaron joins tells Steve Curwood about a new citizen science project to monitor hummingbirds in the US.

Transcript

CURWOOD: The changing climate is impacting birds, from the largest of all to the smallest of small - the hummingbird. Hummingbirds are more fragile than many bird species, in part because their fast metabolism requires nearly constant feeding. Geoff LeBaron is a scientist and the director of the Audubon Society’s annual Christmas bird count. He’s working on a citizen science project called Hummingbirds at Home, where people can share their observations, and I called him up in Northampton, Massachusetts to ask him why it’s important to monitor hummingbirds.

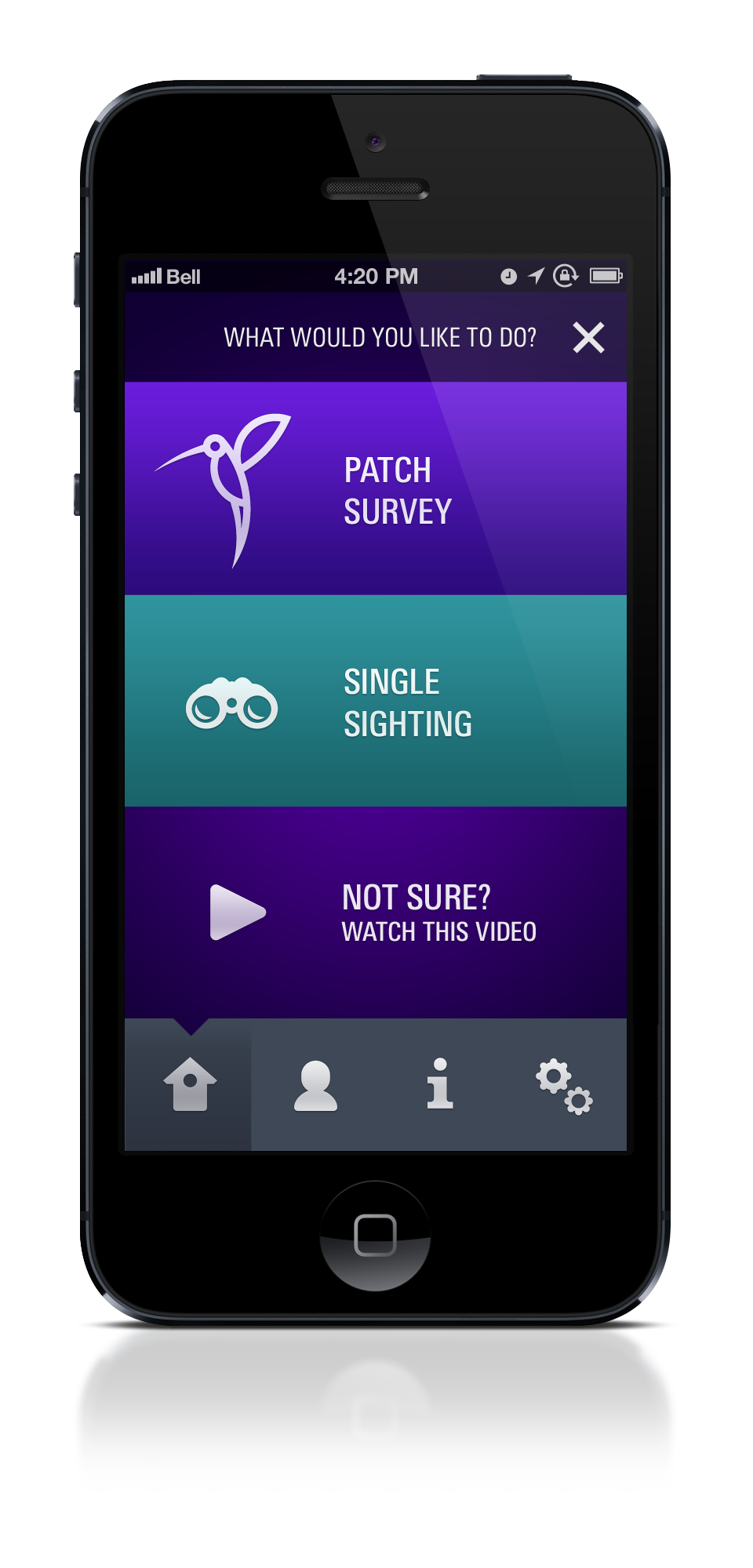

Hummingbirds at Home includes an app to add geographic tags and make hummingbird monitoring easier (Photo: Hummingbirds at Home)

LEBARON: Well, what we’re learning, what we’re realizing, is there’s a growing mismatch in the time when the hummingbirds are arriving here from their wintering grounds and the initial blooming of the wildflowers. When they’re first arriving, they’re very energy stressed and need all the nutrients they can get, especially out west; in some areas of the Rocky Mountains, we’re discovering that the initial flowering is happening as many as two, two-and-a-half weeks ahead of when the hummingbirds arrive. They’re actually arriving at the end of that first flowering, and there isn’t anywhere near as much nectar and resources for them available. So we’re concerned about how that will affect, or how that is affecting, their nesting success, and also their long-term survival and their ability to then head south again for the next fall.

CURWOOD: By the way, how far do hummingbirds typically travel when they migrate?

LEBARON: The two furthest species are Rubythroated hummingbirds here in eastern North America, which travels about, back and forth, between most of eastern North America and northern South America. In the west, the Rufous hummingbird actually goes from Mexico, and they bred as far as southeastern Alaska.

A ruby-throated hummingbird, the hummingbird most commonly spotted in the Northeast, hovers above a backyard feeder. (Photo: Cheryl Gayser for Hummingbirds at Home)

CURWOOD: Wow! So what kind of data do scientists have on hummingbird migrations?

LEBARON: There’s a lot of known data and a lot of people studying arrival dates, and where species of hummingbirds are and at what time, and what’s happening to them in terms of vagrant species showing up in the east, which is happening more and more.

CURWOOD: Vagrant?

The Rufous hummingbird follows the Rocky Mountains to migrate from Alaska to Mexico (Photo: Diana Douglas for Hummingbirds at Home).

LEBARON: Vagrant species in terms of ones that actually aren’t supposed to be here in the fall necessarily. In the east, some of these western long distance migrant birds, that end up in the northeast late in the fall, when hummingbirds should have left.

What isn’t known though is what are the interactions between hummingbirds and their nectar sources. And that’s really what the Hummingbirds at Home project is about. We hope to learn, do they have hummingbirds in their yard, and what nectar sources do they have, including do they have a hummingbird feeder. And as you’ve probably noticed this, if you’ve had a feeder up in the past, and don’t get it up in time, your hummingbirds are going to be buzzing around where that feeder was last year saying ‘where’s our feeder this year?’ They’re incredibly good at learning where the nectar sources are in their territory, and they monitor them on a daily basis.

Geoff LeBaron, Audubon scientist and director of the Christmas Bird Count, monitors the hummingbirds in his backyard (Photo: National Audubon Society).

CURWOOD: So you have an app.

LEBARON: We do.

CURWOOD: Let’s see. I set up an account, and I can enter a patch or list a single sighting. So I click ‘patch’ and a timer starts ticking...and when I see a hummingbird?

LEBARON: When you see a hummingbird you can select...there’s a list of species of hummingbirds there. For us in New England this time of year, it’s just going to be Rubythroated, unless you want a lot of birders visiting your yard, in which case you could try to report something else.

Sometimes Allen’s hummingbirds end up in the Northeast in the late fall after they lose their bearings during migration (Photo: Jack Ludwick for Hummingbirds at Home).

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

LEBARON: So here we would just say ‘yes, I have hummingbirds that are Rubythroated’, and then there’s a box for each nectar source that you can check when you see the hummingbird go to that nectar source.

CURWOOD: So with climate disruption, the temperate zones are moving north. What are the odds that we’ll see different kinds of hummingbirds in the northeastern part of the United States?

LEBARON: Especially in the fall, I think that it’s an increasing pattern that we are seeing. The Rufous tend to migrate over land, so they follow the Rocky Mountains down, and then they really have to make a sharp turn to head south, to head down to Mexico. If there’s a weather pattern. - most of our strong weather comes across from west to east across northern North America - those birds will just continue eastward until they actually get here to the northeast.

So we are seeing an increasing number of Rufous hummingbirds. As more and more of these out of season hummingbirds are being banded, we’re realizing there’s an increasing number of Allen hummingbirds as well, in addition to the tiniest bird in North America which is the Calliope hummingbird, which is another long distance migrant hummingbird, and they show up also here in the northeast late.

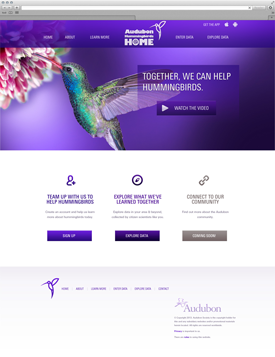

People without smartphones can also log their data using the Hummingbirds at Home website. Once the scientists begin to analyze the data they will post the results here. (Photo: Hummingbirds at Home).

And we are trying to figure out what the long-term ramifications are. For most of these birds, especially the Rufous and the Calliopes, on any given day, they are actually experiencing sub-freezing temperatures because they breed up high in the mountains in the northern Rockies. So it’s not the temperature that is in their detriment, as much as just the lack of nectar source for them if they get up in the wrong place at the wrong time.

CURWOOD: Your citizen science project, Hummingbirds at Home, this year was a pilot season, but I gather you have a fair amount of data. How many folks have signed up for this?

LEBARON: Last I heard, we had 6,000 or 7,000, people, or as many as 10,000. But we’re hoping there will be quite a bit more than that for future seasons.

CURWOOD: Really, what are your aspirations?

LEBARON: The more the better, really. People as you know, love hummingbirds. And in the long term, what we really hope to do is develop guidelines on what people can do in their yard that will actually enhance the survival and chances of reproductive success for the hummingbirds in the area.

Because of their small size, hummingbirds must feed frequently to fuel their speedy metabolism. (Photo: Lea Foster for Hummingbirds at Home).

CURWOOD: Geoff LeBaron is an Audubon scientist and the spokesperson for the Hummingbirds at Home citizen science project. Geoff, thanks so much for joining us today.

LEBARON: Well, thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: There are more details about the citizen science hummingbird project at our website, LOE.org.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth