Gulf of Mexico Ocean Health Update

Air Date: Week of November 1, 2013

PhD student Michelle Masi from the University of South Florida displays some of the data she's gathered on fish stomach contents. By examining the last meal of fish brought in by other researchers, she's helping provide valuable information on who's eating who in the Gulf of Mexico—a necessary step for creating an ecosystem model. (photo: David Levin)

Three years after the BP oil disaster fouled the Gulf of Mexico, scientists are still analyzing the effects on the ecosystems. David Levin (luh-VINN) reports that mathematics and computers are vital tools, as well as field work

Transcript

CURWOOD: Testimony in the multibillion dollar civil damage trial of the 2010 BP Gulf Oil spill recently wrapped up, and US District Judge Carl Barbier is now taking written post-trial briefs before the final penalty phase. That will determine exactly how much BP and its drilling partners must pay in damages under the Clean Water Act.

At the same time scientists continue to assess how the ecosystems of the Gulf are functioning, how they're recovering, and how they might best be protected from another spill. This is an enormous task for researchers. Some are biologists, but there's also a vital role for mathematicians and computer specialists at the Center for Integrated Modeling and Analysis of the Gulf Ecosystem, or C-IMAGE, as reporter David Levin discovered.

LEVIN: It’s been more than three years since the Deepwater Horizon spill hit the Gulf of Mexico, dumping more than 5 million barrels of oil into the ocean. Since then, researchers have been unraveling the impact it’s had on the Gulf as a whole, how the oil moved in the water, how that oil degraded, and how it affected marine animals along the way. But every spill is different, and studying one doesn’t guarantee that scientists can tell how the next one will play out. According to Jason Lenes, predicting that involves serious math.

LENES: You don't truly understand something unless you can describe it mathematically. What we try to do is use math to describe ecosystems and biology.

LEVIN: Lenes is a researcher at the University of South Florida. He’s one of a small group of people using complex equations to build a computer model of the Gulf - a kind of digital reproduction of the entire Gulf ecosystem.

Inside that virtual world, they’ll be able simulate future oil spills, and anticipate how they’ll affect fish and other organisms. But getting the model to work – well, that’s the hard part.

LENES: It's such a large picture, and there's so many questions, in terms of just the ecology itself, let alone the physics. It’s so much information.

Ecological Modeler Jason Lenes studies the fate of tiny creatures in the Gulf of Mexico, like plankton and algae. Based on data collected in the field, he's creating a detailed computer model of their life cycle. (photo: Courtesy Aimee Blodgett / USF)

LEVIN: First, the scientists need data on all the key species in the Gulf, from tiny plankton to huge whales. They have to know roughly how many are out there, where they live, how often they reproduce, how quickly they grow, and most importantly, what they eat. Without understanding the food chain, or who eats who, it’s almost impossible to build an ecosystem model.

AINSWORTH: If you want to make predictions about predators, about fisheries, about recovery time, that information on the food web is really not negotiable.

LEVIN: Cameron Ainsworth works with the modeling team at USF, and he’s trying to simulate the life cycle of fish in the Gulf. He says getting data on what they eat is actually pretty tricky. Most of the fish studies in the Gulf focus on commercial species, like red snapper or grouper, and there’s a lot less information on species fishermen can’t sell.

AINSWORTH: There’s no end to the holes. [Laughs] You know, just the nature of ecosystem modeling is that you’re bound to run into data deficiencies. And, you know, in a lot of cases those can’t be swept under the rug. Sometimes, he says, his team has to fill in the missing data themselves, by studying fish collected by other researchers.

AINSWORTH: What my laboratory did in particular was just survey the gut contents of fish. So we would take fish, bring it into the lab and then dissect it, and try to determine what the species has been eating…

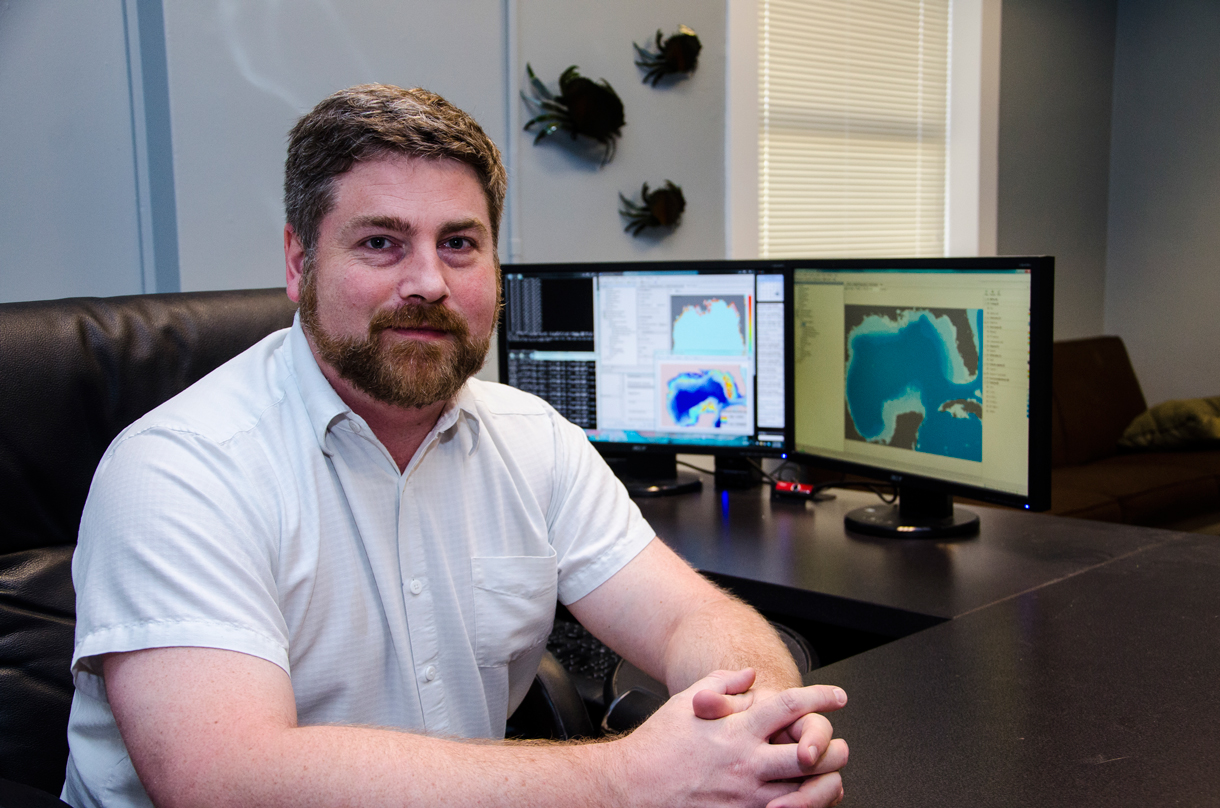

Oceanographer Cameron Ainsworth from the University of South Florida. On the screen behind Ainsworth is Atlantis, a computer model that will ultimately offer a complete simulation of the Gulf of Mexico's Ecosystem. (photo: Courtesy Aimee Blodgett / USF)

LEVIN: For a group that works with computers most of the time, being elbow-deep in fish guts is kind of unusual. But it’s something that Michelle Masi does all the time. She’s Ainsworth’s PhD student. When the fish come in, she spends hours cutting open their stomachs and recording what’s inside.

MASI: So you'd look in there for anything that looks like it might be a little prey item. A claw perhaps, or some bones or scales. If there are scales in there, you know that it's eating fish.

LEVIN: But looking for scales and claws inside fish bellies can only tell you so much about who’s eating who. To build an accurate model of the Gulf ecosystem, you also have to factor in the tiny stuff, like plankton and bacteria. That's where Jason Lenes comes in.

LENES: The stuff that we're trying to model are at the base of the food chain. We're interested in the bacteria, we’re interested in algae, we're interested in the zooplankton, which are the little guys that eat the algae. So we want to see what is the baseline, what is the standard that goes on in the Gulf, and then when you add oil, how that would impact the algae and the zooplankton.

LEVIN: It’s a big job. For every one fish in the Gulf, there are huge numbers of those little critters. And they’re growing, reproducing, and being eaten every minute of every day, so the population can change dramatically in a short time. To keep track of that many organisms, the model Lenes is creating needs some heavy computer power.

Running a computer model of an entire ecosystem involves millions of calculations, and terabytes of data. In order to process that much information, the USF team turns to this high-powered computing center, which uses huge racks of processors to crunch numbers around the clock. (photo: Courtesy Brian Lindblom)

[FOOTSTEPS IN HALLWAY, DOOR OPENS]

SMITH: Hi, Dave,

LEVIN: Hey, nice to meet you.

SMITH: Good to meet you. So we're going up to the third floor where the data center is at...

LEVIN: Brian Smith oversees the University of South Florida's research computing center, the place where Lenes runs his models. He leads me into a squat brick office building, through a maze of cubicles, to a glass security door.

[SWIPE CARD BEEPS, DOOR OPENS, WHOOSH OF FAN]

LEVIN: Inside is the heart of the system. It’s a huge white room filled with racks of powerful computers. The fan noise is deafening.

SMITH: It's high performance computing. Lots of processors, lots of memory, very fast network. So we can actually take one simulation and run it on all these machines simultaneously in order to harness all of their power.

LEVIN: Even with all that computing power, the millions of calculations that Jason Lenes needs for his model can still take up to a week to run. And that’s just his latest version, which covers only a small fraction of the Gulf.

At the moment, he’s working on expanding and perfecting the model. Next, he plans to combine it with Ainsworth’s fish model, and together, they’ll create a simulation of life in the Gulf that covers everything—from the tiniest microbe to the biggest whale.

AINSWORTH: Yeah, that’s our hope.

LEVIN: Again, Cameron Ainsworth. He says that once the full ecosystem model is up and running, it’ll be incredibly useful for studying future spills, and testing how they might affect marine life.

AINSWORTH: For a given level of oil concentration, how do we expect fish to be impacted? What’s the impact on growth, on longevity, on their ability to reproduce and things like that. So I think what we hope to get is a little bit of a better perspective on what to do in the case of the next oil spill which is surely coming.

LEVIN: In other words, with more than eight thousand oil wells in the Gulf, it’s only a matter of time until another disaster. In the past, scientists have had to react to those spills after they happen, but using these models, they might be able to predict how they’ll play out ahead of time. They’ll know which fishing grounds should close first, which species will be hardest hit, and ultimately, what the impact will be on people in the Gulf.

For Living on Earth, I’m David Levin in Tampa, FL.

CURWOOD: David's story comes to us from Mind Open Media. To learn more, dive into our website, LOE.org.

Links

USF College of Marine Science homepage

Center for Integrated Modeling and Analysis of the Gulf Ecosystem (C-IMAGE)

USF Fisheries and Ecosystems Ecology Lab (Cameron Ainsworth's Lab)

Collaboration for Prediction of Red Tides (Jason Lenes' Lab)

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth