Climate Change Tourism in Peru

Air Date: Week of November 15, 2013

Pastoruri Glacier in the Andes was once a destination for outdoor enthusiasts and skiers. Today the glacier has melted so much people are no longer allowed to walk there. But Reuters reporter Mitra Taj tells host Steve Curwood that Peru has come up with another way to make money from the glacier; climate change tourism.

Transcript

[MELTING GLACIER SOUND]

CURWOOD: Melting ice isn't only a problem up in the Arctic. Glaciers are quickly melting in mountains in the tropics. And a case in point is the one-time skiing tourist destination in the Andes in Peru called the Pastoruri Glacier. Mitra Taj is a correspondent for Reuters, and a former producer and reporter for Living on Earth. We reached her in Lima, Peru, where the government is working on a novel plan to address tourism in the face of the rapid retreat of the glacier, and the prospect of its disappearance within a few years.

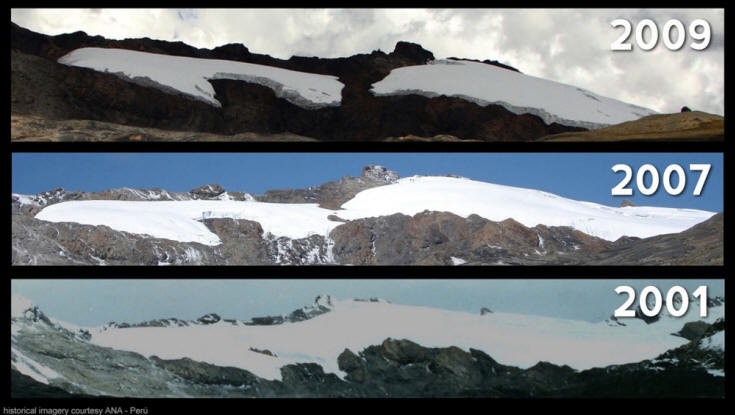

TAJ: The pictures that you see in the nearby city of Juarez in hotel rooms and hotel lobbies and restaurants, you see this big glacier, and there’s people all over it skiing, climbing, having a good time...you don’t see that anymore. You mostly see a big block of ice, and a lot of exposed rock around it, so black rock that used to be covered completely in snow and ice.

Pastoruri Glacier in 2010 (Wikimedia Common)

CURWOOD: So how has the melting glacier affected the regions around it? How’s tourism doing?

TAJ: Pastoruri was the big tourist attraction for a long time. It drew a lot of Peruvians from Lima and nearby cities and towns because it’s just a day away, and you can have fun with your kids. So now that it’s no longer drawing people because it doesn’t look the way it used to look, and you’re not allowed to climb on top of it, and stuff like that, the number of visitors has dropped pretty dramatically, from about 100,000 per year to just 30,000 last year.

CURWOOD: So I gather the plan is to figure out another way to get tourists there by making it a climate change tourism destination? What’s going on with that so far?

TAJ: I think they’re targeting tourists that are interested in things like science and climate change, and also people that want to see something that might not be around that much longer, and you’ll hear them talk about what it used to look like. You know, this used to be an international skiing destination, we used to have international ski competitions here; we used to see children running along and building snowmen, and you contrast that with what you see now and the changes that are happening as a result of the glacier melt, and it’s unique I think in terms of travel destinations.

CURWOOD: Now, other than being a tourist destination, I’m sure the glaciers are also an important source of water for local people. How are they being affected by this rapid melting?

Peru is home to some 700 glaciers. (Bigstockphto.com)

TAJ: That’s an interesting topic. I don’t think there’s been any very serious studies done on it yet but as the water’s melting off it’s taking minerals with it that used to be buried in snow and ice and sort of frozen into place, and that’s more and more of a concern...there’s levels of heavy metals that are unsafe for drinking. The local water company that provides water to the city of Juarez actually had to change the river that it gets its water from because levels of metals were so high that it wasn’t really safe for drinking.

CURWOOD: Pastoruri Glacier isn’t the only one melting in the Andes. This is a regionwide phenomenon, I would imagine.

TAJ: Yes, Pastoruri is in the national park of Huascaran, which has, I think, 700 or something glaciers, and they’re all melting very quickly. In the past few decades, in total, Peruvian glaciers in the Andes have melted to 30 to 50 percent of their previous size. It’s happening really quickly, that tropical glaciers are some of the most sensitive formations to global warming which is why it’s easy to watch them and see what’s actually happening, and that they reflect the global temperature rise really well.

Iceberg off the coast of Greenland (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: What do you think the average person living in this area thinks about this melting glacier in terms of climate change? Do they make the association?

TAJ: Oh, yes. You can ask anybody that lives in these towns near the glaciers and I think it’s very clear that it’s climate change. They can talk to you what it used to look like, about how it’s much brighter now, the sun shines harder. I don’t think there’s any doubt in their mind that climate change is driving this.

CURWOOD: Mitra Taj is a correspondent for Reuters. Thanks so much for taking the time today, Mitra.

TAJ: Thank you, Steve.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth