Antarctic Volcano

Air Date: Week of November 22, 2013

Mt. Sidley is the largest known volcano in Antarctica. Unlike the active one found under the West Antarctic ice sheet, Mt. Sidley hasn’t erupted in millions of years. (photo: Doug Wiens)

Many scientists are concerned about the impact global warming is having on the Antarctica, and Doug Wiens from Washington University in St. Louis tells Steve Curwood that he’s discovered a new kind of threat lurking beneath the vulnerable West Antarctic ice sheet—an active volcano.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. For years scientists have been concerned that a warmer Earth might lead to the melting and sudden collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet, which could add as much as ten feet to world sea levels. Now scientists at Washington University in St. Louis have discovered a surprising new threat lurking beneath the West Antarctic ice sheet - an active volcano. Joining us to discuss the finding is Douglas Wiens, professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Washington University. Welcome to Living on Earth.

WIENS: Thank you. I’m glad to be here.

CURWOOD: So, imagine that! A volcano beneath Antarctica, huh?

WIENS: Well, we’ve known there’s volcanoes around Antarctica, but what’s kind of unique about this one is it’s below about a mile of ice.

CURWOOD: Where is it exactly?

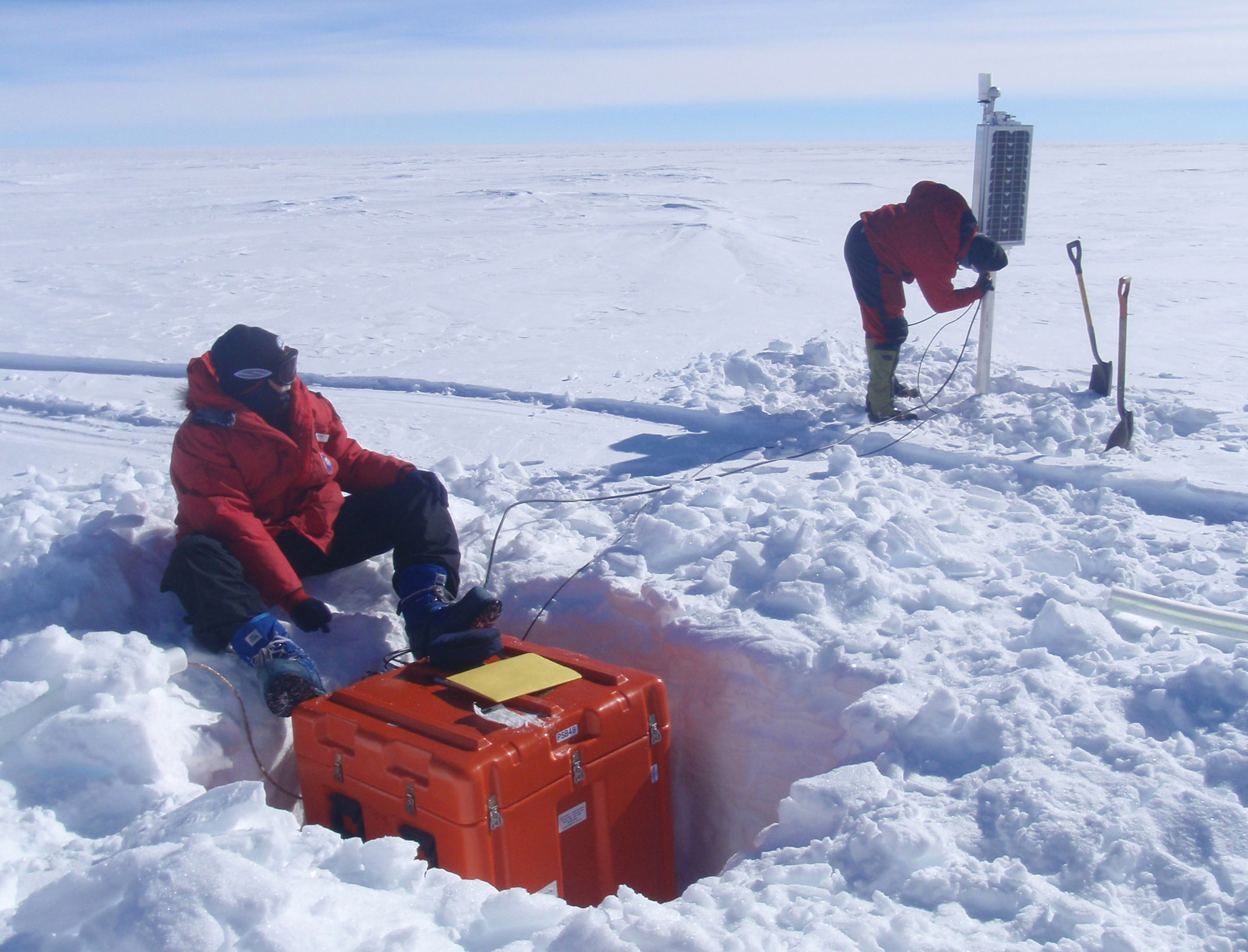

Installing seismographs in the ice (photo: Doug Wiens)

WIENS: There’s a remote corner of West Antarctica called Marie Byrd Land. It’s maybe about 400 miles from the coastline.

CURWOOD: So where it is in West Antarctica, this is under the West Antarctica ice sheet?

WIENS: Yes.

CURWOOD: So when’s the last time you think this volcano blew?

WIENS: We have no way of knowing. So in 2010, we went out and put seismographs in this area, and as soon as we put the seismographs down they were recording these small earthquakes that are related to the movement of magma beneath the ice sheet. So we don’t really know when the activity started, we think this activity does not mean there’s an eruption going on now, but there could have been an eruption almost any time in the past and we wouldn’t know.

Installing the equipment (photo: Doug Wiens)

CURWOOD: So how many volcanoes are down there do you think?

WIENS: Well, that’s a really good question. I think there’s quite a number of undiscovered volcanos across west Antarctica. There’s a few of the big ones that stick out, so like this newly discovered volcano is about 30 or 40 miles from Mount Sidley, which is this spectacular volcano that sticks out of the ice sheet and was first discovered by Robert Byrd when he flew across Antarctica in the 1930s. But that volcano hasn’t erupted for three million years so we had no idea whether volcanoes in this area were currently active.

CURWOOD: So what are the chances the thing underneath the ice erupts?

WIENS: Well, we would think it would be pretty good. If you have this kind of volcanic earthquakes, they’re only found beneath active volcanos such as in Cascadia, in Pacific Northwest, or Alaska or Japan or Hawaii. Those are places where active volcanos have had this kind of earthquakes beneath it. So we think that there’s a pretty good chance that at some point in the future this volcano will erupt.

Amanda Lough, the lead author on the paper in Nature Geosciences (photo: Doug Wiens)

CURWOOD: And the question is, of course, how soon?

WIENS: How soon and how large of an eruption? And we really don’t know much about what happens when a volcano erupts under this much ice. I mean there’s a lot of study of volcanoes in Iceland, for example, that erupt beneath a few hundred feet of ice, but beneath a mile of ice is something we haven’t really considered very much.

CURWOOD: What happens in Iceland?

WIENS: Well, in Iceland, they have something called a jokulhlaup - I don’t know if I’ve pronounced it exactly right, - but basically a lot of water builds up underneath the ice as the volcano heats up, and then it all of sudden rushes out towards the ocean in kind of a catastrophic flood. Something somewhat similar may happen in Antarctica, but here the ocean is about 500 miles away, so the water has to go a long way.

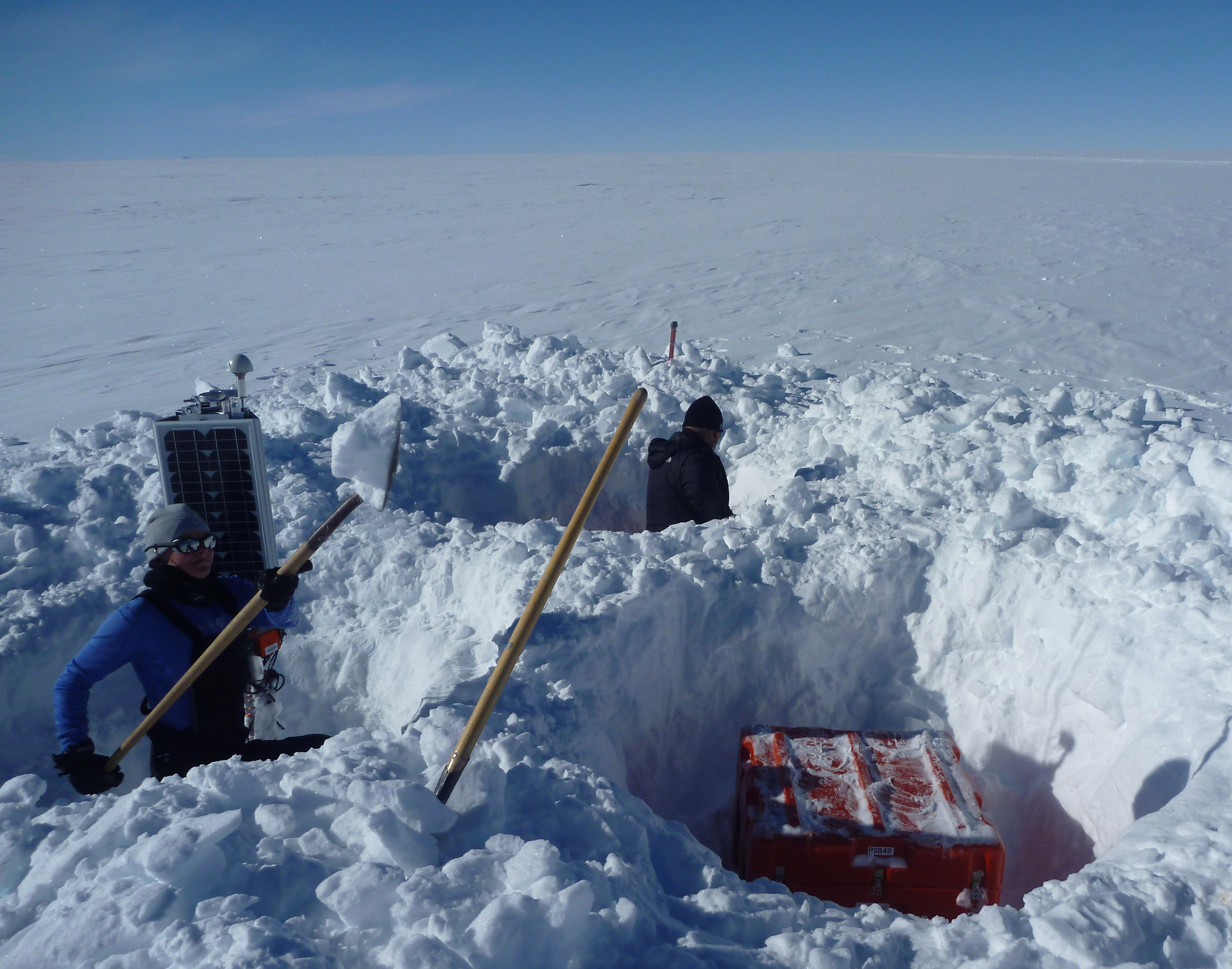

Scientists burying seismographs in the icepack of Antarctica (photo: Doug Wiens)

CURWOOD: What are the odds an eruption could melt through the ice sheet?

WIENS: Well, we did a little calculation for our paper for Amanda Lough, that’s my graduate student for her paper in Nature Geosciences, and her calculation suggested that if we had a really really large eruption, like some of the most famous large eruptions in history like Krakatoa or Mount Tambora, that such an eruption would melt through the ice sheet and vent to the atmosphere, but that a small sort of garden variety eruption would not and would essentially build up a large amount of melted water beneath the ice.

CURWOOD: West Antarctic ice sheet is kind of like a boat run aground. What are the odds that this volcano could help push portions that ice sheet into the ocean?

WIENS: Well, we don’t think this volcano would catastrophically melt the West Antarctic ice sheet. I think that’s probably out of the picture. An eruption like this though could perturb the ice sheet and maybe for a period of years cause increased flow of the ice sheet towards the oceans, and so that would maybe increase the rate of melting for a while. I wouldn’t encourage any sort of doomsday scenarios though with the volcano. There is a larger question in West Antarctica which is what is the amount of heat coming into the bottom of the ice sheet from the Earth, and how does that affect the ice sheet and its behavior?

Doug Wiens outside his tent in Anarctica (photo: Doug Wiens)

CURWOOD: OK. So you asked the question and what do you think the answers might be?

WIENS: Well, there is some evidence recently that the heat flow into the bottom of the ice sheet is larger than what we thought. So there was an ice core in the West Antarctic ice sheet ice drilling project at a place called Wais in west Antarctica, and it has found a higher level of heat flow that anybody thought. So there are indications like this volcano, like this high heat flow measurement, that the heat flow is higher in West Antarctica than we previously thought.

CURWOOD: And that means the water would be going back to the ocean which of course would raise sea level if that ultimately happens?

Doug Wiens looking a little icy (photo: Doug Wiens)

WIENS: Yes, because if the ice moves faster from the middle of Antarctica to the edges, it doesn’t melt in the middle. We’re there on the hottest day of the year and it’s way below freezing. The ice only melts at the edges though, and so the faster that the ice moves from the center to the edges, the faster that the ice is going to melt, and so that’s what we’re really worried about. How fast is that ice moving from the center to the edge and how is that going to change in the future?

CURWOOD: Douglas Wiens is a Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Washington University in St Louis. Thanks for taking the time today.

WIENS: Yes, thanks for having me on your show.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth