Inheriting Fear

Air Date: Week of December 20, 2013

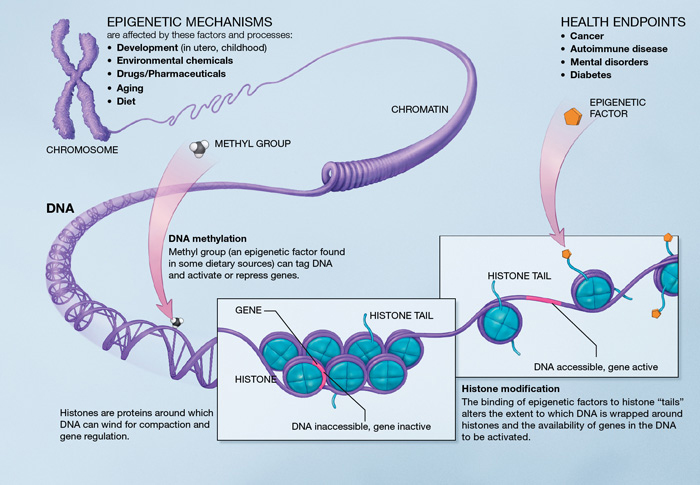

This diagram shows the method by which epigenetics works. (Wikipedia Commons)

Moshe Szyf of McGill University tells host Steve Curwood about new research demonstrating that fear can be passed on from one generation of laboratory animals to the next. Epigenetic changes are most likely responsible, and this provocative study is bringing new challenges to how scientists think about behavior and evolutionary change.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Whenever we welcome a new baby into a family, someone's bound to say, "Look, he has his father's eyes," or "She has her mother's hair." For most of us, that's how we understand inheritance, that we get particular physical characteristics from our parents. But new research recently published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, based on lab animal research, has found that direct experiences and fear could be transmitted down through generations. We turn now to Moshe Szyf, a professor at McGill University in Montreal, to learn how the experiment worked.

SZYF: What the researchers did was to expose a mouse to a smell, and at the same time, shock the mouse with a mild electrode shock. So now the mouse associates the smell with the shock, and whenever the mouse will smell that smell, then the mouse will startle because the smell reminds the mouse of the shock. This is a known property of animals, they recognize smell that protects them from fearful experiences, for example, mice and rats are afraid of fox urine, and that makes sense because a fox is a predator of a mouse, and this way the mouse can recognize when there’s a fox around and survive.

CURWOOD: So how did they transmit this to their offspring?

SZYF: So usually this is selected probably by natural selection. Animals that acquire mutations during their evolutionary lifetime that protect them and allow them to survive against their predators, probably that’s how mice recognize fox urine. But in this case, this was not going through natural selection because the mouse passed it directly to its offspring, through the sperm.

CURWOOD: So the offspring...this worked in the first generation as well as the next...

White mouse (Bigstockphoto.com)

SZYF: The second. I think it went up to two generations.

CURWOOD: So if we were talking in human terms, you’re talking not just a child, but a grandchild.

SZYF: A grandchild who will remember an experience like this. Yes.

CURWOOD: How is this possible? How could the children and grandchildren of the original mouse fear something that they never experience themselves?

SZYF: We don’t know how this could happen. I mean, I still...you know, it sounds like science fiction. This idea that experience can direct the phenotype of the next generations, is very problematic and controversial because we don’t have a clear mechanism, however, what is coming up in the last decade, that it’s possible there is a epigenetic mechanism that allows this to happen, that is, the experience changes the epigenetic state of the sperm, and I’ll explain immediately what’s epigenetic, and that sperm is now marked, and can pass this mark to future generations.

CURWOOD: Yes, I’m ready to hear the explanation of what exactly is epigenetics and how that works.

SZYF: So epigenetics is the additional information on genes. So we inherit from our parents the genes, and they are inherited in a very accurate way from generation to generation, and up until now we thought that only those genes are inherited from generation to generation, and therefore there was no way an experience could be inherited from generation to generation. But now we know that genes are programmed, and that programming involves marking of the genes by chemicals, and also packaging the genes in chemical material. And that will define if a gene works or not. So, for example, if the experience managed to change the way a particular gene is marked in the sperm, that mark could be passed to the next generation, and indeed, what the authors have shown is that a chemical mark on the gene that codes for the receptor of this specific smell was changed in this way, and that was probably passed to the next generation.

CURWOOD: But what evidence do we have that epigenetics works from one generation to the next?

SZYF: The evidence is still sparse, but there is accumulating evidence. There are epidemiological studies from humans that show that experiences could be transmitted across generations, and the most famous one is the Dutch famine of 1944, and these are Dutch who were exposed to very low calories, punished by the Germans, and we see now phenotypes in their grandchildren, metabolic phenotypes, and there is a suspicion that that was an epigenetic transmission of the experience of famine. You know, the famine during the pregnancy of their grandmother kind of adapted them to a lifetime of famine, right? And in a life of lack of food, you better binge on every food you find, and turn it into fat. But what happens when the grandchildren are born into a rich Dutch society? That preparation by the experience becomes maladaptive.

Moshe Szyf is a professor in the department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics at McGill University. (McGill University)

In animals there is evidence that certain exposure of chemicals, like Skinner’s work, could be passed four or five generations. And in that case it was pesticides, then there is evidence about depression and aggression. So there is evidence that experiences could be passed from generation to generation, and exposures could be passed from generation to generation. But what’s unique about this paper is that it points to a specific gene, a specific receptor, and a specific smell. This idea of smell-fear is so fundamental in evolution because it is something that is required for animals to protect themselves from their prey, and it was always believed that the way that is generated is through natural selection. This is the first time we have an epigenetic mechanism for that.

CURWOOD: So first time that instead of being hard-wired this a the function of one’s parents or grandparents’ experience.

SZYF: Right.

CURWOOD: What do you suppose is the role of epigenetics in evolution? I mean, it would seem that the fear response that was found in mice is evolutionary adaptation, but is expressed far more quickly than we typically think evolution could do.

SZYF: Absolutely. The classic evolutionary theory is basically what we call natural selection, which is there are random slow-changing genes that are selected by environment, and those few individuals that are selected would eventually form founders of the next generation of animals and all the others will disappear, and that’s how natural selection works. That’s a very slow process, and epigenetics introduces a whole new speed to that process because in difference from natural selection, which is random, this process is directed. If indeed epigenetics works in evolution, it will change all our calculations and the whole way we look at the way species originated and the way species evolve.

CURWOOD: So, what about those things that we just usually call “instinct”, and what I’m thinking of now is the generational migration of Monarch butterflies, right? It’s the fourth generation of Monarchs. They migrate thousands of miles from the north back to Mexico to the exact same tree where their great-grandparents started the migration months before to a place where they’ve never been to themselves.

SZYF: Right.

CURWOOD: No one really seems to know how they do that. I’m just wondering if epigenetics could be an explanation.

SZYF: Epigenetics could be a very interesting way of explaining that, and, in my opinion, probably the only way. I don’t know about anybody that has actually demonstrated that there an epigenetic change in these butterflies, but epigenetics might play a big role in those transgenerational experiences that are so dominant in the animal world.

CURWOOD: This research really raises a lot of questions, of course, about people and acquired behavior. I mean, what about people born and raised in cities with a lot of crime and violence. Does this study indicate that they might be more prone to living a life of involving crime and violence? Is there--are we talking about learned behaviors or would epigenetics be a factor?

SZYF: Being born in an aggressive environment causes changes by itself, and so you can pass from generation to generation aggression just by the behavior. So if the father is aggressive, and the child is born into an aggressive family, the child will become aggressive and so you don’t need sperm to transmit that, you can transmit it through behavior. But epigenetics could be a factor and if part of it is indeed transmitted through the generational line, it makes it harder to solve, right, because if it’s behavioral, if we change the environment, we can change that. But if it was already transmitted in the sperm, how can you change that?

CURWOOD: What could be the dark side to this? I mean, you talked about depression going down generational lines, aggression going down generational lines.

SZYF: I think the dark side is that, to a certain extent, you’re a consequence of the sins of your father, but there is an optimistic side to epigenetics. Genetics is final. Once you change the sequence, it’s impossible to change it back, whereas epigenetics is reversible. So if experience could create epigenetic marks, there should be experience that could remove epigenetic marks, and therefore, there might be a way that, even if you inherited dreadful experiences from your past generations, that a different experience will be able to remove it, and that might guide a lot of our behavioral studies and research in the next decade.

CURWOOD: Moshe Szyf is a Professor in the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics at McGill University. Professor Szyf, thanks so much for taking this time with me today.

SZYF: Thank you.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth