A Window On Eternity

Air Date: Week of July 4, 2014

Elephant in tall grasses (Photo: Gorongosa National Park/ Michael Paredes)

Pulitzer Prize winning author and Harvard biologist, E.O. Wilson, talks to Steve Curwood about his new book A Window on Eternity. Wilson describes Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park and its many unique and extraordinary species and how biologists were able to reintroduce large mammals like hippos and buffalo after they were wiped out in a series of armed conflicts.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Pulitzer Prize winning author and Harvard biologist E.O. Wilson is perhaps best-known for his detailed work on ants. But Professor Wilson recently traveled to Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique to study wildlife on a much larger scale—elephants, baboons, buffalo—as the park rebuilds from the loss of almost all of its large animals during armed conflicts. His new book detailing this experience is called A Window on Eternity, A Biologist's Walk Through Gorongosa National Park. Professor Wilson stopped by our studio to talk about the park.

Elephants (Photo: Piotr Naskrecki)

WILSON: The main vegetation of Gorongosa Park is savanna and seasonal dry forest. It is an environment in which humanity evolved. Every species of organism that is mobile—that is, moves around—has a favored habitat, and I believe the same thing is true of human beings—that we have an ideal habitat. And that habitat would be the one in which our species evolved, and if that's true it helps to explain why the African savanna, exemplified so marvelously by Gorongosa, has inspired poets, novelists, all kinds of people to say essentially the same thing: “I felt at home here. I felt good. I really like this place.” They saw this part of Africa, particularly around the great African drift, as something special, emotionally.

The savanna of Gorongosa National Park (Photo: Gorongosa National Park/ Piotr Naskrecki)

CURWOOD: At Gorongosa, the war there in Mozambique between the government and the RENAMO, supported by the apartheid of South Africa, meant that virtually all the large, the megafauna—the big animals: hippos, elephants, lions—I think in your book you say everything down to about ten kilograms; twenty, twenty-two pounds was pretty much eaten. But now today a lot of animals have returned. What's there now, and how are they able to make this return?

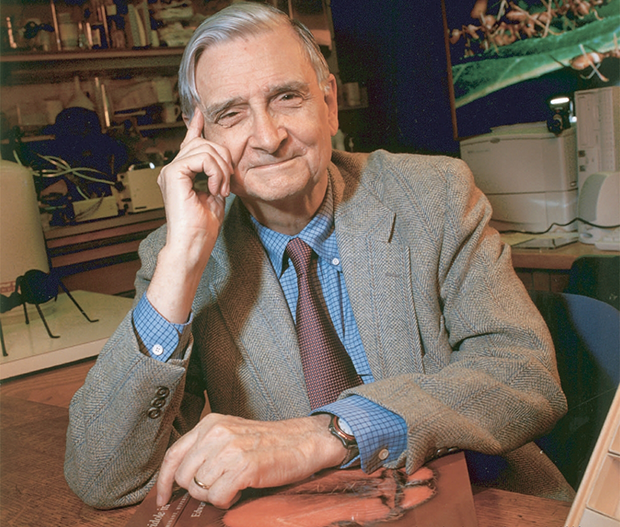

E. O. Wilson (Photo: Piotr Naskrecki)

WILSON: Yes, a few species did survive in small numbers, maybe a dozen or so elephants. There were a couple of Cape buffalo and so on, and Greg Carr, who’s been masterminding the re-building of the game, the big animals, got animals for breeding purposes, and released them from the surrounding countries. And so we are in the process of building up a healthy lion population; as they say, what a wonderful thing to hear the roar of these returning lions around you in the dark, in the evening. And every other species except for a few that are just too dicey to get back in right away, including the cheetah, is being returned.

During Mozambique’s series of wars almost all large animals, such as hippos, were eradicated from Gorongosa National Park. (Photo: Gorongosa National Park/ Steve Le Vourch)

CURWOOD: Let’s talk for a moment about the elephants in the park. There’s a small population there and some of them must have been there during the Civil War as well. Biologists speculate that they're living with something akin to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Could you tell me about that—what you saw, what you heard?

The elephants of Gorongosa Park suffered from something akin to PTSD following the years of conflict in Mozambique. (Photo: Gorongosa National Park)

WILSON: Yeah. They’re the most aggressive elephants in Africa, and the reason appears evident that a few young elephants witnessed the slaughter, brutal slaughter, of their brothers, sisters, their parents and so on. These young elephants that had the trauma survived, as matriarchs today, and they visibly are agitated by the approach of people. They are much shyer than elephants elsewhere, and they’re much more likely to charge if you get them in any kind of a situation where they appear trapped. But there're easing up now. One of the leading authorities on elephant biology and behavior, Joyce Poole and her brother Bob Poole, they went out and over long period of time, simply parked near browsing elephants and did nothing—just sat there talking quietly. Gradually the elephants calmed down. They “habituated,” is a word we use in animal behavior, to the two humans. And the result is, they’re much more peaceful, but you're advised not to go out alone, stand in front of a matriarch and wave a big flag or something.

E. O. Wilson examines an orb weaver spider web. (Photo: Gorongosa National Park/ Bob Poole)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Now part of your reason for traveling to Gorongosa National Park is to catalog its diversity, particularly the diversity of insects, spiders living in specific areas within the park today, and you call part of that effort, a bio-blitz. Please tell me about a bio-blitz and what you found.

A lion from Gorongosa National Park (Photo: Gorongosa National Park/ Michael Dos Santos)

WILSON: Well, a bio-blitz really—I conducted the first one in Gorongosa—and the idea is bringing people into the study of biodiversity, and it's especially effective with school kids—to invite everyone in, to join in a search for all organisms, and make a complete census. And included among all the invitees, of course, are all the experts that might or might not be in the area to assist in this. And it’s sort of a combination treasure hurt, serious natural history search, and just community activity, which is wonderful. We are just beginning to find out what’s in that park. In a model, for example, the great Smoky Mountain National Park, one of the few parks in the world that is striving for complete census of its biodiversity, have yielded eighteen-thousand species of organisms, with an estimate of as many as sixty-thousand present. In a tropical, extremely rich environment like Gorongosa, I think we're eventually going to find into the hundreds of thousands of species of organisms in that one park. And it’s then we can come fully to understand how these ecosystems work. Here then is an area for pioneering in a major part of biology.

A local researcher observes Matabele ants. (Photo: Gorongosa National Park/ Piotr Naskrecki)

CURWOOD: Now your expertise and some of your fame, of course, could be attributed to the studies that you’ve done on ants. In your book, A Window on Eternity, you talk about the Matabele ants and what they do to termites. Could you describe that for me please?

WILSON: Oh, yes. Everywhere you go in the park, you're likely to find an army of Matabele ants crossing the trail. Big black heavily-armored warrior ants moving in a group of anywhere from maybe fifty or a hundred to over a thousand. They are moving in a way I have never encountered in any other social insects, ants, termites or whatever, as a solid group—all of them close to the fellow ants around it and all moving in the same—as one body of ants charging along. You see them crossing the road, and it’s part of the wildlife spectacles of Gorongosa because the local people have a custom, superstition: do not cross or ride over a Matabele column; it’s bad luck. The column is on its way. They've been aroused in their nest by scouts.

Ants (Photo: Piotr Naskrecki)

Scout Matabeles can be seen out wandering the ground, the countryside out as much as a hundred yards, and when a scout finds a termite nest or opening into one that allows an army to come, to break in, it runs straight back to the nest. And by means of some communication we do not know, arouses the warrior ants, the adults, and out they come in a solid body marching together, behind the scout ant. They arrive at the termite nest, and they just crash through the entrance. And the termite mound—termite nest, I should say—responds by sending down, or in that direction, large numbers of soldier termites. So what ensues in the mounds and all around the entrance is open battle between the Matabele and the termites, which are smaller, they’re armed, but their soldiers are smaller. And the Matabele ants always win. The termite soldiers are always killed. And as the battle subsides, each Matabele worker gathers up as many dead soldiers or termites as it can and almost by signal, the entire group, each one carrying a bunch of dead soldiers in its mandible, marches in the same formation back. And at the nest, they eat the termite soldiers. That’s what the Matabele feed on—they’re specialists. In other words, they go to war in order to collect dead soldiers of the enemy for dinner.

An image from E.O. Wilson’s book, A Window on Eternity (Photo: Gorongosa National Park/ Piotr Naskrecki)

CURWOOD: Interesting way to live and eat. Tell me about the ants that would clean your house.

WILSON: Driver ants which is what you’re referring to.

CURWOOD: Yes.

WILSON: They have swarms of up into the millions because each colony can have over twenty-million workers, always under orders of the single queen. People have known for millennia that when these Driver ants arrive at your house, get out of their way and let them go into the house, and just go away and have a cold drink somewhere. After a few hours, the army passes on through, and it's caught, massacred, carrying all this food, every cockroach, every lizard, every kind of spider or anything it finds in the house, it cleans out. And as the army of Driver ants recedes in the distance, why, you can return home—a home that’s been perfectly cleaned for you.

[LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: What are the take-home lessons from your time at Gorongosa?

E. O. Wilson is a biologist and author. (Photo: Wikipedia Commons)

WILSON: There are a number of take-home lessons in Gorongosa. We have in Gorongosa, as we do in parks elsewhere around the world preserved at least to an important degree, these immensely complicated ecosystems. And they evolved over three-and-a-half billion years, overall globally, three-and-a-half billion years to what they are today. And we’re not going to find out how they work any more quickly than we’re going to find out exactly how the human mind works. So we should regard this as a major area for future biological research and not just an interesting place to visit. We should plan land-use globally that includes substantial parts of the world set aside for the rest of life, and allow it to continue indefinite time, eternity if you will, on its own like a parallel universe as we learn more and more about it.

CURWOOD: E.O. Wilson’s new book is called, A Window on Eternity, A Biologist's Walk Through Gorongosa National Park. Professor Wilson, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

WILSON: It’s been a privilege.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth