The End of Night

Air Date: Week of July 18, 2014

Light pollution in major cities prevent many people from experiences natural darkness and a clear night sky (Photo: Tom Bricker; Creative Commons 2.0)

Humans have always had a basic fear of the dark, but the advent of electric light in the late 19th century brought control over the night in the developed world. But with an explosion of light pollution blocking out the natural night sky in much of the world, host author Paul Bogard tells living on Earth’s Helen Palmer we might have gone too far and it might be harming our health.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. One of the glories of the summer, the Perseid meteor shower, comes up in August, putting on an amazing show for stargazers in the Northern Hemisphere. That’s assuming one can find a nice dark place to watch it. Most of us now live where the advent of electric light has banished the darkness, too much so, says Paul Bogard. His book called The End of Night has been shortlisted for the PEN/E.O. Wilson Literary Science writing award. We found Paul Bogard’s thesis intriguing, so Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer got in touch with him.

PALMER: So Paul, you grew up in the countryside in Minnesota. Tell me about your relationship with the dark when you were growing up and how did that influence your decision to write this book?

BOGARD: Well, we were lucky enough to have a cabin in the northern part of Minnesota, so all my life I've come to the woods here by a lake, and I've experienced real night, real darkness, standing on the end of the dock with more stars than you could ever count, and woods so dark that you can't see your hands in front of your face. And I think it's that first-hand experience, especially as a child, that just imprinted on me how beautiful darkness can be, how beautiful the night can be, and when it came time to learn the constellations - which was actually after college - I quickly found out that we've lost so many of the constellations, so much of the night sky, because of light pollution and that we need darkness to see the stars. And from there it just kind of led me to understanding how important darkness is for so many reasons.

PALMER: So in fact the world's really changed—you talk about light pollution. I mean, we haven't really had electric light for that long—basically since the end of the 19th century, but it's changed most dramatically in the last couple of decades, I think.

BOGARD: Yeah, it's really true. It's, you know, I like to say that it's happened very quickly when you look through the course of time as you say, most significantly just over the last two or three or four decades, but just slow enough that we haven't really noticed the lighting on the gas stations and parking lots in the U.S. It's about ten-times as bright as it was just 20 years ago. And I think, you know, if that happened from one night to the next, people would be alarmed and obviously they would notice and think maybe we don't need all this light, but because it's happened so gradually over the last 20 years we tend not to notice. And we just tend to think that all this light is normal.

Paul Bogard met many dark sky enthusiasts who seek out the earth’s darkest places (Photo: Jay Raz; Creative Commons 2.0)

PALMER: I learned reading your book there's actually a scale where you can measure this—measure all this light. It's called the Bortle scale - could you tell me about that?

BOGARD: Sure, the Bortle scale is a scale that astronomers use to really gauge the levels of darkness. The scale starts at 9 in our brightest places, like Las Vegas or Times Square or really the downtown of any major city, and it works its way down to 1, which would be no evidence of artificial light in the sky or on the ground. And the significant thing for me with that scale is a couple of things: One is that most Americans live most of their lives in levels five and above, and rarely or never experience anything darker, and then what's even more troubling is that when I started the book and I began to ask folks where I could go to experience a level 1 on the scale, they recommended the outback of Australia, or other places like that. They said, "You know, we might not even have any of those nights left in the U.S."

PALMER: Do we? I mean, are there any number ones left here in the U.S.?

BOGARD: You know, what they told me is that—and when I say they I’m talking about the National Park Service's Night Sky team—they go around measuring the levels of darkness in the national parks. Dan Duriscoe, who's a friend of mine and who was kind enough to take me with him out into Death Valley, told me that he's taken measurements in more than 200 locations in the U.S., and he's only ranked three of them as a level 1 darkness. So, they're very rare at this point.

PALMER: Now, one of the reasons I think that people have embraced light is basically this fear of the dark. Do you think that's really what’s at the base of this growth in light?

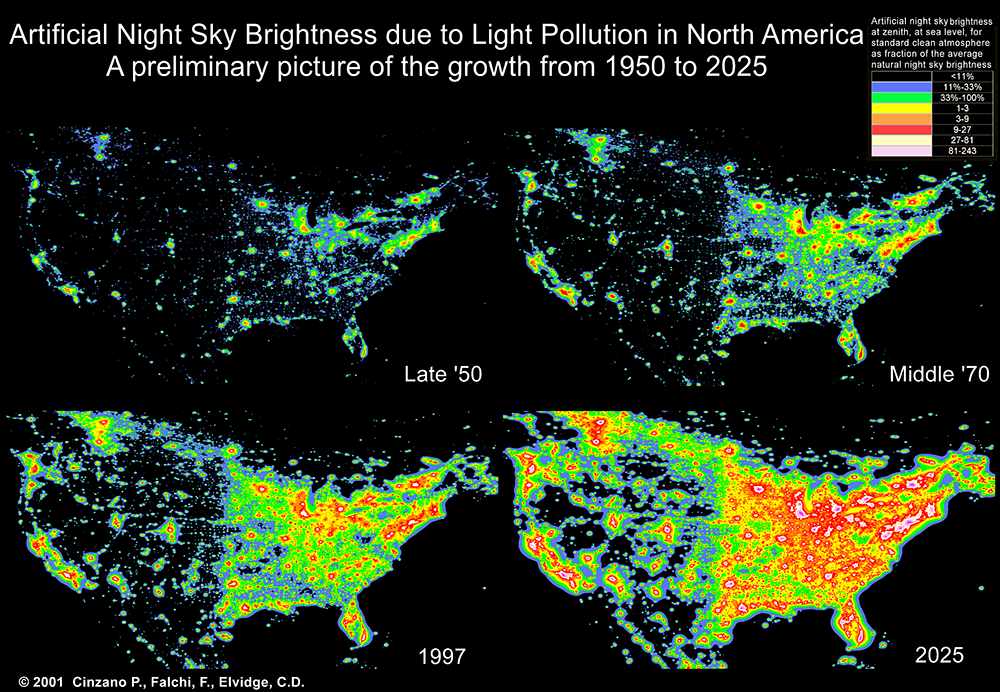

Growth in light pollution in the last 75 years (Photo: P. Cinzano, F. Falchi [University of Padova], C.D. Elvidge [NOAA National Geophysical Data Center, Boulder]. Copyright Royal Astonomical Society. Reproduced from the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astromical Society by permission of Blackwell Science)

BOGARD: Well, you know it's a complex problem, a complex issue, but I do think that we have a basic fear of the dark. [LAUGHS] I sometimes laugh because I admit in the book that I'm afraid of the dark, and people think, you're the guy who wrote the book on the value of darkness, how can you be afraid of the dark? But I think it's a perfectly natural thing to be afraid of the dark. I think what's not natural is to then compensate for that fear by trying to light up our nights as bright as our days and to think that we can somehow do away with darkness by turning up the lights ever brighter.

PALMER: But I think there is this feeling that with light will come security, you know. You have this feeling of the murderer or the thief sort of lurking in the darkness, and so obviously, we turn on the lights to become more safe. Has it made us in that way more safe, or does more light make us more safe?

BOGARD: Yeah, sure, I think that's really at the heart of it. When you ask people, you know, do we need all this light? People say often times, "Well, yeah, we need it for safety and security." But the truth is that well, some light can help us be more safe and secure, and no one's suggesting that we just turn off all the lights. But what people are suggesting is that we don't need all this light for safety and security and that in fact, when you have ever more light, you often create more problems than solutions. Oftentimes when you have lights that are too bright, they cast shadows where the bad guys can hide. There's so much light in our nights that are glaring lights that make it hard for us to see. And then also too much light which tends to create the illusion of safety; we think we can be reckless purely because it's light out, and that's obviously not the case.

PALMER: So basically, it destroys our night vision as well.

The Bortle Scale (Photo: The International Dark Sky Association)

BOGARD: Yeah, it really does. I mean, one of the most startling estimates that I found when I was doing the research for the book was that some 40 percent of Americans and Western Europeans ever experience or rarely experience night vision. We're in the light so much that our eyes never switch to night vision.

PALMER: You told that very sad story of somebody saying, "What are all those white dots up in the sky?"

BOGARD: [LAUGHS] Exactly. You know, if you live in a major urban area, major city, you're not seeing anything close to the night sky that we ought to be able to see, and I had several nights where I was traveling for the book where, say, I was standing on a bridge in London, and I looked up and I could count about 20 stars. And that's nothing when it comes to the night sky.

PALMER: Well, it's not only our inability to see the stars that's the problem. You actually point out that this excess light is actually making us sick.

BOGARD: We're learning more and more. More and more research is showing us that light at night, in fact, is impacting our physical health, and in three primary ways. It is interrupting our sleep and contributing to sleep disorders, which are tied to every major disease that we're dealing with now. It's confusing our circadian rhythms, those internal rhythms that orchestrate our body's health, and then perhaps most troubling, it's impeding the production of the hormone melatonin. Melatonin is only produced in the dark, and what scientists are finding is that a lack of melatonin in our bloodstream is linked to an increased risk for breast and prostate cancer. So, nobody's saying yet that light at night gives you cancer, but what everyone I talked to did say was, we've evolved in bright days and dark nights just like all life on Earth. And we need both for optimal health; to think that we can simply flood our nights with artificial light and have it not have an effect on our health is probably foolish.

PALMER: Obviously one thing that I know, night workers complain of is that they all put on weight. It seems that somehow it really upsets the circadian rhythms in terms of digestion as well.

BOGARD: Yeah, it really does, and I think, you know, the folks that are bearing the brunt of all this light probably most directly right now are those people who are working the night shift or rotating shifts, and that happens to be more and more of us. And too often, it's the poorer folks who need to work at night. But I talked to a number of folks who work the nightshift who have put on weight and just say it's really, really difficult to live this way. You feel exhausted all the time; you feel tired all the time. And they can sense that it isn't right, but they have to do it.

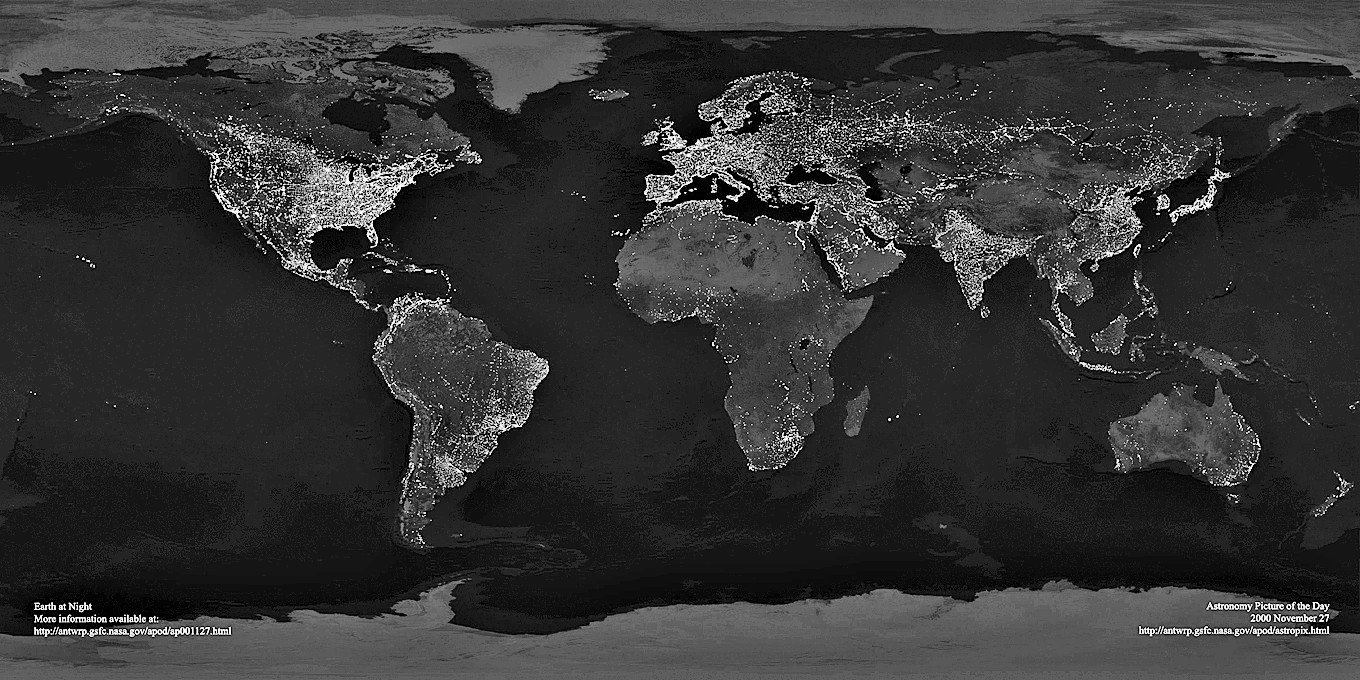

The earth at night (Photo: C. Mayhew & R. Simmon (NASA/GSFC), NOAA/NGDC, DMSP Digital Archive)

PALMER: Well, even if we actually sleep in a theoretical dark room, there are all sorts of LED lights—the little lights on the alarm clock by our bed, the lights on our watches, the lights on our phones—it's amazing if you just look around the bedroom, theoretically the dark bedroom, what’s still on.

BOGARD: [LAUGHS] It's true. We have lots of little lights, and I think though that a lot of folks aren't even aware of how important it is to be sleeping in the dark—to pull those shades completely shut and to turn off the lights in the hall room. And to, if you get up to use the bathroom in the middle of the night, to not turn that bright light on.

One thing that researchers are seeing a lot of is that people are doing a lot of reading on the computer or on the tablets, their phone, what have you, right up to the time they turn off the light and go to sleep at night, and this keeps the production of melatonin from starting when it normally should. What scientists are finding is that it's the blue lights in the screen that's having the most negative effect on her physical health. And, you know, a lot of the new LEDs that were seeing in our streetlights and in a lot of our gadgets and that kind of thing, are really heavy with this blue-rich white light that we really shouldn't be seeing in the night.

PALMER: Of course, people like the idea of LEDs because they're much more energy efficient, and everybody's thinking, oh, this could be a really good answer to how much electricity we're using all the time, but you're saying this actually may be doing a number on our melatonin production and our health.

BOGARD: When I talk about LEDs I like to say, you know, they're full of promise, but they also may be full of peril. They're full of promise because they do immediately cut our energy use, our electricity cost, which is obviously a good thing. They're highly programmable so that a city could have a system of streetlights where, maybe they're a little bit brighter during rush hour, maybe they're a little bit darker or even off at three o'clock in the morning when we don't really need all that light. But the peril is that, at least right now, a lot of the LEDs that we're seeing are full of this blue-rich white light, and they also tend to be brighter than a lot of the lights that they’re replacing.

PALMER: Do you think there's a kind of spiritual aspect to this, the excess of the light and the harshness of the light?

Excessive glare from artificial lights can actually make it more difficult to see people lurking in the night (Photo: George Fleenor)

BOGARD: Oh, I think absolutely. I think it all goes back to being able to see a real night sky or not. You just to start to think about all the different inspirations that come from standing face-to-face with the universe, whether it's religious or spiritual or just thinking about your life. I think, sometimes I say, think of all the young van Goghs out there who haven't been inspired to paint a night sky because they've never seen something like that. When you're standing there under the stars you can feel really small, like your troubles aren't so bad, but you can also start to feel how wonderful life is here on earth and how we need to take care of everything that we have here.

PALMER: What about the rest of life on Earth, all the other species that we actually share a planet with. What effect are we having with all this light on other species?

BOGARD: Well, it seems like we’re having a tremendous effect. A couple of specific examples: Many people have heard about the sea turtles in Florida that have come ashore for hundreds of millions of years to lay their eggs and those baby turtles when they hatch—they've evolved to swim or scurry to the brightest light on the horizon, which for all those hundreds of millions of years has been the stars and the moon reflected on the water, but now it's the hotels and parking lots in the wrong way, and migratory birds are drawn off course, for example. Bats are impacted. The wild world comes alive at night and really needs darkness, and we benefit from that as well. So, it's important that we cut down our use of light for our health; it's also important that we cut down on the use of light for the ecological health.

PALMER: One of the things you're doing in your book is going around searching out these advocates for dark skies across the world, actually there seem to be many of them. What did they advise or could we basically do to reverse this trend of ever-brighter, ever-brighter, ever more destructive?

Paul Bogard (Photo: James Madison University)

BOGARD: Well, you know, I'm optimistic about it. I think there's a lot that we can do, and it starts with the way that we use light. And I like to say that light at night is not the problem, it's how we use it—so that is true in our homes where we can have light that is shining only downward; we can turn off our lights when we go to bed. That continues into our communities where we can have a lighting ordinance in our communities that will describe the kind of night that we want to have in the places that we live. Most of us don't want to live in places with glaring super bright, ugly lights. We prefer to have lighting that is subtle and nuanced and maybe even beautiful, even as it provides us with the safety and security that we know we want. So from the individual all the way up to the community and even on the statewide level, there are things we can do right now to begin to control this.

PALMER: Things like downward pointing streetlights and stuff like that you're talking about?

BOGARD: Absolutely. You know, one of the biggest problems that we have with our lighting, one of the, I guess, basic problems is that we have light shooting in all directions right now. We have light that's being sent straight into the sky; we have light that's being shined into our eyes as we drive down a street. And we have too much light that's just shining from one neighbor or one streetlight into our houses, and none of that light is doing any good. In fact it's just all a waste of light. So simply by directing our light downward just to where we need it, we can have a huge positive impact.

PALMER: Now, one of the things you did in your book was to go around visiting various national parks, and you end the book with a visit to Great Basin National Park in Nevada, and that's a very dark place not far from a very bright place, Las Vegas. You go stargazing there with a group of amateur astronomers. Can you take us out by reading the final page please?

BOGARD: Absolutely. So the epigraph for my book—and I come back to it at the end here—is a really beautiful poem by Wendell Berry, and I'll read that and then read to the end.

“I think of the Wendell Berry poem I have carried with me while writing this book.

‘To go in the dark with a light is to know the light.

To know the dark, go dark. Go without sight,

and find that the dark, too, blooms and sings,

and is traveled by dark feet and dark wings.’

How upside down this world where what was once a most common human experience has become most rare, where child might grow into adulthood without ever having seen the Milky Way and never feel as though lifted from Earth into surrounding stars. Where most of us go into the dark armed not only with a light, but with so much light that we never know that the dark too blooms and sings.

How right it feels to be in this place standing with dozens of others gazing at the Milky Way. How right it feels to know a true night sky; how right to know the dark. And as my companions and I head back toward the parking lot, back toward the light, I let the others walk ahead and turn one more time before I go inside, before the lights take my night vision. To see in that darkness our home in the universe, the rising ribbon of billions of stars slashed overhead, horizon to horizon, just as it always has been.”

CURWOOD: Paul Bogard’s book is called The End of Night. He teaches English at James Madison University in Virginia. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth