The State of the Planet

Air Date: Week of October 3, 2014

|

The World Wildlife Fund recently released its 2014 Living Planet Report, which studied 10,000 wildlife populations across the globe to assess the overall State of the Planet. Host Steve Curwood discusses the report with WWF’s Director of Renewable Energy and Footprint Outreach, Keya Chatterjee, who argues the sharp decline in wildlife numbers as human population has grown shows there’s an urgent need to limit our global ecological footprint.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. According to the World Wildlife Fund, since 1970 numbers of vertebrate animals are down more than half, with one exception, and that would be humans. WWF has just released its 2014 Living Planet Index, which estimates that numbers of vertebrates - fish, amphibians, reptiles and mammals other than humans - are declining even faster than earlier studies have shown. The bulk of the losses come from habitat degradation and exploitation, especially in the tropics. There is some good news, though, and it’s that some cities have made considerable progress towards sustainability, even though human population has doubled. On the line now is Keya Chatterjee, Director of Renewable Energy and Footprint Outreach at WWF, to detail what’s in the latest Living Planet Report, and why it matters.

According to WWF, fishing practices in French Guiana threaten leatherback turtles. (Photo: Courtesy of WWF)

CHATTERJEE: It’s sort of our State of the Planet report. We put it out every two years, so we can have a science-based analysis on what the human impact on Earth is. And we want to have a consistent data source so we can look at what the trends are over time and how we’re doing as far as the way that we impact the planet in terms of species, abundance, and also the human ecological footprint—so a measure of consumption of goods, greenhouse gas emissions, and the impact that we're having on the planet.

CURWOOD: Give us the report's good news first.

CHATTERJEE: I think the good news is very much at the local level. Just a few weeks ago at the UN Climate Summit we saw for the first-time city leaders being recognized for the role that they're playing in tackling climate change, which gives me great hope, along with the other thing that we saw a couple weeks ago, the People's Climate March. Seeing so many people pour out into the streets and ask for better choices from their leaders gives me incredible hope.

CURWOOD: OK. Now, it's time for the bad news, Keya. Your report sounds an alarm about declining biological diversity and wildlife populations. Tell me, which species are in the worse shape?

The Humphead Maori Wrasse, whose habitat includes the Great Barrier Reef, is an IUCN Red List Endangered Species. (Photo: Courtesy of WWF)

CHATTERJEE: There have been dramatic declines across the board—almost 40 percent decline of all terrestrial species, almost 40 percent of all marine species, and a huge decline in freshwater species, more than 75 percent. The data sets that we use go back to about 1970, and the Earth's human population in 1970 was just under 3.7 billion. And today we're at 7 billion. While the number of animals have been cut in half, the human population has nearly doubled.

CURWOOD: Help me with the math. So if you had said that there was 100 percent decline in species, it would've meant that they all went away.

CHATTERJEE: Yes, so there's been about a 50 percent decline in species over for 40 years.

CURWOOD: And in Latin America you're saying that there's more than 80 percent decline, in other words, more than four out of five are gone?

CHATTERJEE: Yeah, and part of this, of course, is that in the tropics there are more species than in higher latitudes, and you have more abundance in the tropics. But it is a really dramatic decline, and a huge part of that is related to deforestation. And a huge part of that deforestation is related to the consumption patterns that we have here in the United States. Every time we throw away food in United States, for example, that's food that was grown somewhere on this planet for us, and water that was used, and fertilizer that was used. There's a huge amount of this resource consumption that is driving deforestation, that is driving species decline, but the good news is that we are responsible for a lot of this, so we have a lot of ability turn things around. None of these trends are inevitable. We can turn them around today.

The Ethiopian wolf is a Critically Endangered species. (Photo: Courtesy of WWF)

CURWOOD: What's the strategy that the World Wildlife Fund has for counteracting all these losses that you describe in your report?

CHATTERJEE: What we want to do is engage people in this process, in caring about what's happening out there. I think it's really easy for people to not be shocked when data like this comes out—for people to say, "Oh, yeah, I knew things were bad. I knew things would get worse." But people should be shocked. We've become so desensitized to this violence against our planet that we aren't even shocked when we hear this information. We are working towards engaging the American public so that they are the people who care. I was just watching “The Lorax” with my son yesterday, and it struck me that in 1971, Dr. Seuss wrote this book, and it says, "unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing's going to change, it's not." That's still the message that we have today.

CURWOOD: So what can I do? What difference can I make today?

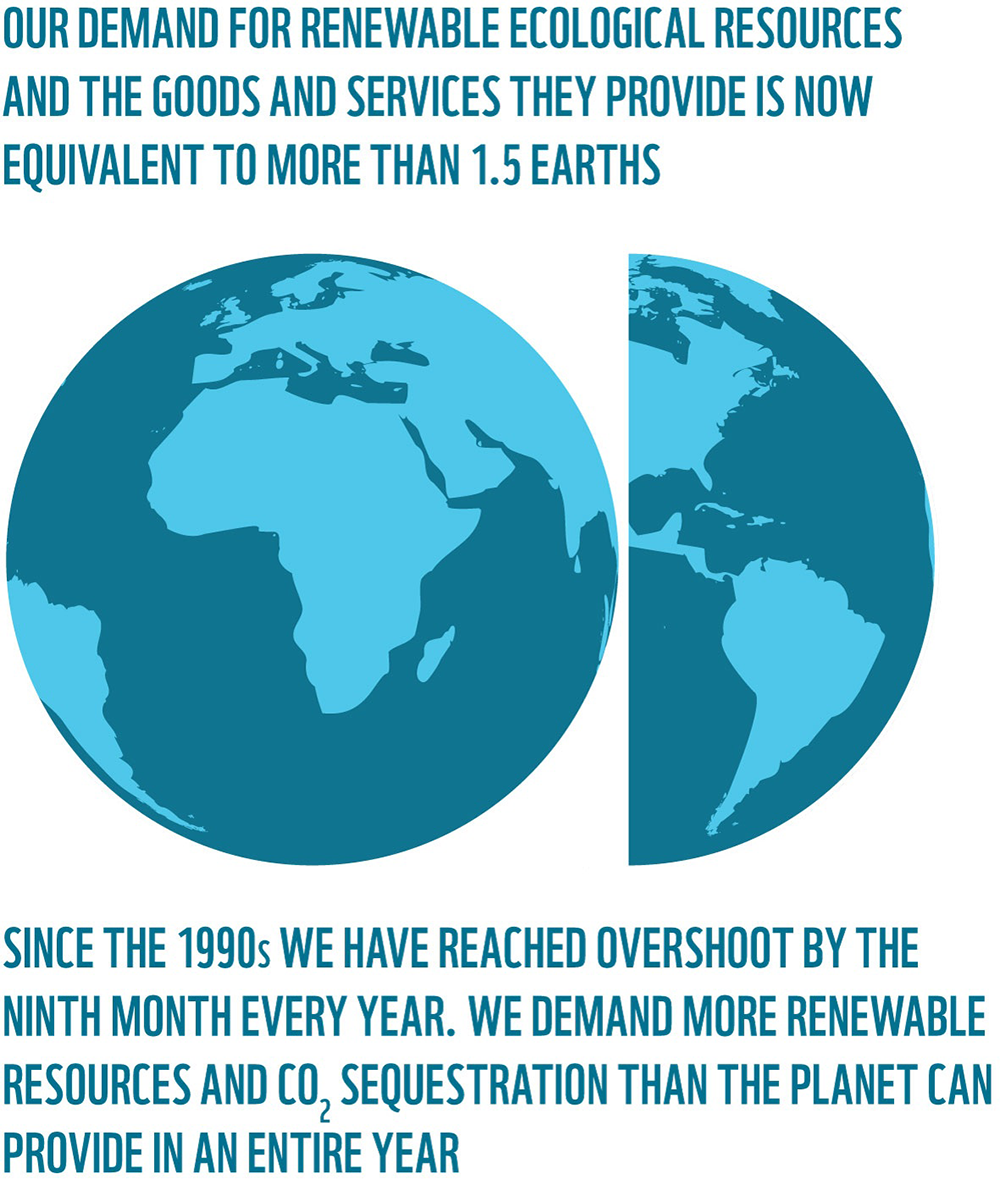

The world is running a deficit: Humans place too much demand on the Earth for its goods and services, and it now takes 1.5 Earths to recycle and regenerate the resources that we require per year. (Photo: Courtesy of WWF)

CHATTERJEE: Well, there's three areas that people make a huge impact in their homes and workplaces. One is electricity, two is transportation and three is food. There's so many things that can be done in each of those areas that save money, save resources, and are just better choices. If you live in a transit-oriented place, everybody knows public transportation and bicycling are good choices. But some of these new technologies that we have and electric vehicles are great options for people who don't live in transit-oriented areas. Around electricity there's a similar suite of options that people have, whether they own their roof and can install solar panels, or whether they sign up for renewable energy through their bill or focus on using less energy in the home. We need everybody to realize that this is not inevitable. We can each make better choices. We can demand more of our leaders: when we go to vote, we can ask people, "What do you plan to do about the food waste crisis? What do you plan to do about the climate crisis?" and then we can vote accordingly. We can demand that we work our way to a sustainable future.

In March 2009, WWF France celebrated its 35th anniversary and raised awareness of giant panda threats by staging 1,600 paper maché pandas in public spaces of several French cities. (Photo: Stéfan; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: You mention population pressures, that we've gone from three-and-a-half or so billion people to about 7 these days from about 1975 or so. What about the choices people are making in terms of having families?

CHATTERJEE: One of the equations that has come out of the population arena is that the impact that we have on the planet is this balance between the population, the number of people, the technology that they're using and the actual rates of consumption. I think, unfortunately, the population conversation has at times devolved into this conversation about how people in other countries shouldn't have so many babies. And I think it's important for us to think about it's not just the number of people, it's how they consume. And here in this country, we're consuming an awful lot. We've got to learn how to live on the one planet that we have.

WWF members participated in the NGO march at the UN Climate Change Conference of Parties (COP) 18 hosted by Doha, Qatar in November 2012. (Photo: WWF International Photo Coverage for Climate COP17; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Keya, the United States is just about the only major industrialized nation whose population is rising rapidly. We're going from about 300 million or in the year 2000 to as much as 420 million by the middle of the century. This has an impact, I imagine, on biological diversity. What kind of other choices should Americans be making in terms of population?

CHATTERJEE: I'm a parent myself, and I think there's two lenses through which parents can make the choice to do everything in our power to bring about a more sustainable country. For me, the most important one is honestly that this has to be done. I see it as my job to protect my child by moving our society in the right direction. The other lens is the additional responsibility that we have as parents having brought more people into the world. Absolutely I think that brings additional responsibility to be more sustainable. The reality is that the United States is a country where our emissions per capita are unnecessarily high. We have the technologies that we need, the economics are there for these changes, and what we now need is a movement that brings about the political changes that we need. That's what parents need to be focused on, is really engaging civically and demanding more from our elected officials.

Keya Chatterjee is the WWF’s Director of Renewable Energy and Footprint Outreach. (Photo: Courtesy of WWF)

CURWOOD: And to what extent should we be thinking about not having as many babies?

CHATTERJEE: Whether to have a baby is a super personal decision, and I think that people who choose to adopt, it's actually a really great decision for the planet. Not everybody makes that decision, I didn't make that decision, right? And the best thing I've done in my life is bring my child into the world and I will say that for me personally it brought about a renewed sense of commitment. So I actually wrote a book called the "Zero-Footprint Baby" that was all about my effort to make our carbon footprint as a family go down, even as we added a person. It's not easy, but it's absolutely possible. And if you can do it, you're doing so much more than reducing your carbon footprint, you're showing all your friends, all your neighbors and our society what the future looks like, what it looks like to live sustainably.

In April 2008, a WWF ad illustrated how forests are “the lungs of the earth”. (Photo: Brett Jordan; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Zero-Footprint Baby, that's the name of the book?

CHATTERJEE: It is. Yes.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] That's cool. Keye Chatterjee is Director of Renewable Energy and Footprint Outreach at the World Wildlife Fund. Keya, thank you so much for your time today.

CHATTERJEE: Thank you so much for having me.

Links

Read the WWF’s Living Planet Report 2014

Browse Keya Chatterjee’s website and her book, The Zero Footprint Baby

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth