In Hotter (Sea) Water

Air Date: Week of October 10, 2014

The NOAA ship Ka'imimoana was used to launch Argo floats into the ocean. (Photo NOAA; CC Government)

As the climate warms, scientists are increasingly concerned about where the atmosphere’s heat has gone. Host Steve Curwood discusses new measurements in a study that has found estimates of ocean warming off by more than 25 percent, with Dr. Paul Durack of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Harvard Prof. James McCarthy, tells Steve Curwood that while this answers some questions, there are still mysteries in the deep ocean.

Transcript

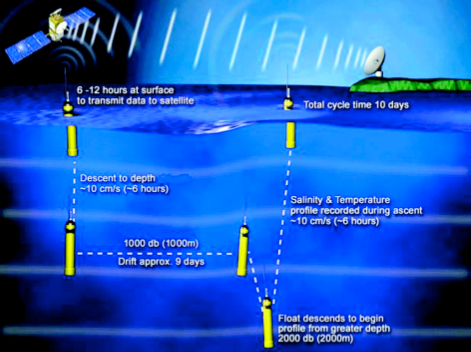

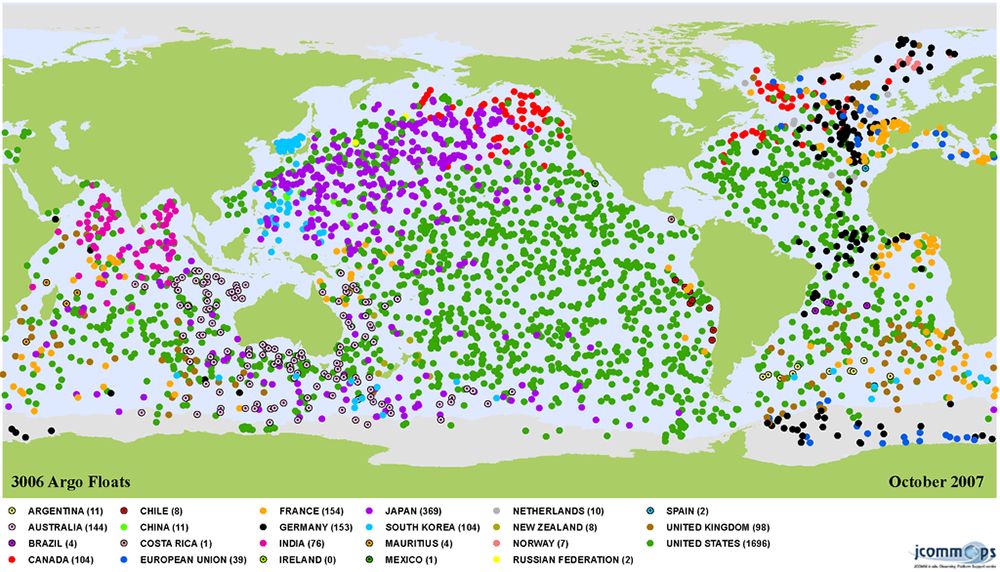

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Science tells us that burning lots of fossil fuel and cutting down lots of trees is warming the Earth, but just how fast and where all the added heat is going has been unclear, though the oceans seem most likely. Now new research based on temperature readings taken over the past decade of the upper half of the seas, is bringing more clarity - and concern. It’s based on the international program called Argo that by 2004 had deployed some 3,500 robotic buoys measuring sea temperatures down to 6,000 feet. Dr. Paul Durack and his colleagues at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory compared the new Argo data with ocean models and satellite readings of the ocean surface.

Scientists deploy an Argo float off of the side of a NOAA research vessel. (Photo NOAA; CC Government)

DURACK: So, what we actually did was we’re basically revisiting estimates of temperature changes in the ocean. And what we found was that there’s an underestimate of how the oceans are warming by a factor of 25 percent or more due to poor sampling of the southern hemisphere that this study has uncovered. So, it’s really not a small adjustment when we consider this analysis with the measurements of ocean warming.

CURWOOD: Some suggest these data indicate the earth is warming at the faster end of current estimates, but as Professor James McCarthy, a Harvard oceanographer points out, there’s still a lot to learn.

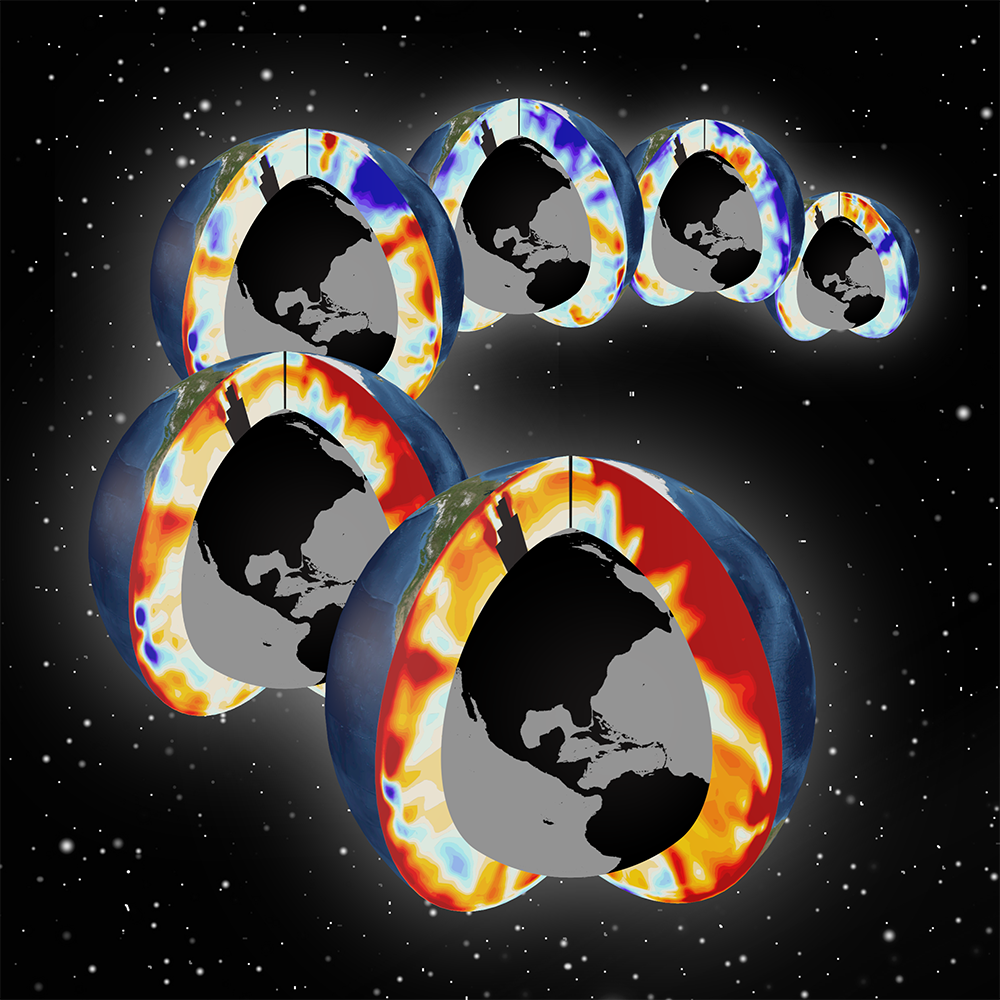

Pacific and Atlantic meridional sections showing upper-ocean warming for the past 6 decades, 1955-2011. (Photo: Timo Bremer/LLNL)

MCCARTHY: So, we talk a great deal about how much the surface of the Earth or the surface of the ocean is warming, and that’s what people look at when they look at a trend—the ups and downs from year to year—but over the last few decades now that we’ve had really good data from the deep ocean, we’ve seen that most of the warming that’s occurring is not in those surface measurements, it’s in the interior of the ocean. So 93 percent - is the best estimate - of the amount of warming that the Earth has experienced with the greenhouse gases we’ve added is in the deep ocean. So when we look at the surface signal of up one year, down the next year, up the next year, down...we’re looking at a very, very small part, and that’s why it’s important to look at these trends in the deep ocean.

MCCARTHY: And what this particular study shows is that in one area of the ocean, the South Pacific—so the Pacific Ocean’s the largest ocean. It covers a little over 40 percent, and more than half of that is south of the Equator. The South Pacific is a region that we have very, very sparse data. This paper uses a variety of approaches to now see whether or not our historic estimates of the heat content of that part of the deep ocean - and here I’m saying deep, but we’re talking about only to 2,000 meters, so 6,000 feet - that’s only half of the depth of that ocean, but we now have data for that upper half of vast areas of the ocean that before were poorly, poorly quantified.

A float mission composed of drifting at a shallow pressure level and then sinking to a deeper pressure level for profiling to the surface. (Photo: NOAA)

CURWOOD: Over the years, the computer models of the Earth’s climate have consistently underestimated the rate of change, how fast again the terrestrial area might be warming. To what extent does this new data make computer modeling more accurate?

MCCARTHY: Well, it makes the modeling, not necessarily more accurate, but it helps us understand where the various components are, that is, where they are in terms of contributing to the warming, and helps us understand what in the past had been talked about, imbalances or the missing heat. So the big mystery that still remains is: what’s happening even deeper than 2,000 meters, 6,000 feet, in other words, the other half of the deep ocean. And this is an area where now the data are really sparse. Some people say, you know, we know more about the surface of the moon than we do the deep ocean. We know more about Mars than we do parts of the deep ocean.

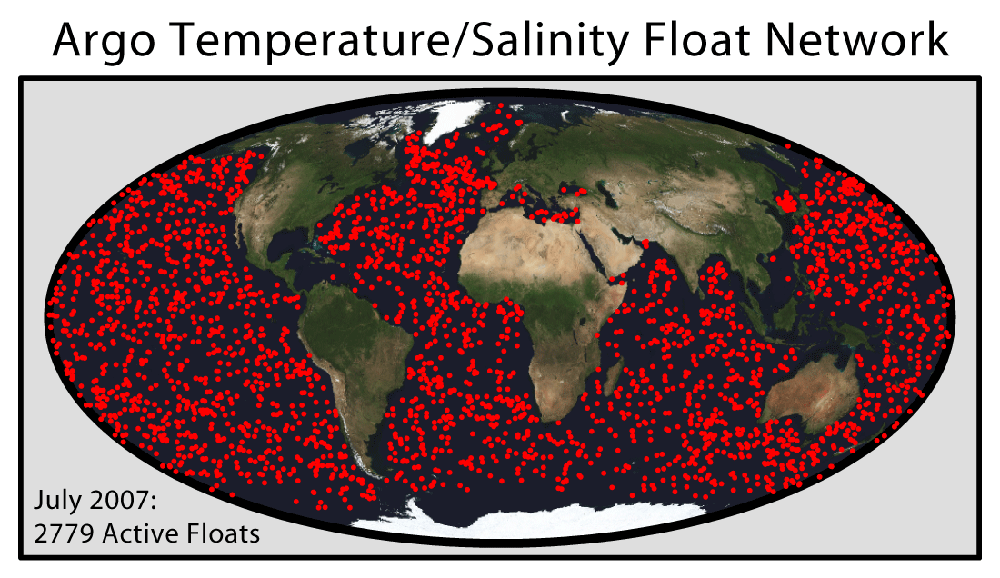

This map shows the distribution of the Argo float network, an internationally managed system of ~3000 free-floating temperature and salinity sensors deployed throughout the oceans. These sensors communicate via satellite, drift on ocean currents, and have the ability to submerge to a depth of ~2 km to create vertical profiles. (Photo: Dr. Robert A. Rohde; Wikimedia Commons)

MCCARTHY: So it’s a frustration for ocean scientists that the resources just haven’t been there to understand what’s happening in the deep ocean. So we have a really good data for the upper 2,000 meters, with the Argo array that had global coverage beginning a little over a decade ago, so they’re 3,500 of these floats, over two dozen nations participating in this really, very successful oceanographic effort. So when people begin to make calculations now about what’s happening in the deep ocean, without observations, we don’t have a really good way to reconcile or to confirm or refute some of those calculations.

CURWOOD: There was an article, recent article in Nature that said that we ought to ditch this two-degrees centigrade warming goal for the Earth for policy. What sense does that argument make to you?

Argo Float Network spans the globes oceans, but the majority of the buoys are in the Northern Hemisphere (Photo: Mathieu Belbeoch; CC-BY-SA-3.0)

MCCARTHY: It’s a very thoughtful critique by a couple of people who are very experienced in this area: Charlie Kennel and David Victor. And when they say we ought to ditch the two-degree, I think they’re saying two things: one is that we’re not doing a very good job in attaining that goal. It’s such a vague process that, having agreed to that, how we’re actually going to do it. And their argument is: “We’re not really making progress so we ought to be realistic about that.”

Host Steve Curwood with Harvard Professor of Biological Oceanography, James J. McCarthy, as he explains the Expendable Bathy Thermograph (XBT). These were deployed around the globe, but primarily in the Northern Hemisphere beginning in 1970. (Photo: Lauren Hinkel)

MCCARTHY: But they also point that the debate about whether these recent trends in surface temperatures indicate the Earth is not warming as rapidly as we thought or not—that’s a really poor indicator, that two degrees—and they think it would be better to develop some sort of composite index that would look at other vital signs, if you wish, of the planetary climate system such as the deep ocean, how rapidly is it warming, such as the loss of arctic ice. So I think there’s a lot of value to that argument, and I think partly it’s a wake up call. But if you look at those deep ocean numbers, it’s a very real thing. So I think it’s something we really need to think about.

Professor James J. McCarthy describes how the Expendable Bathy Thermograph drops a weighted sinker that records temperature data and transmits it. The copper wire snaps at a depth of about 700 feet and the torpedo-shaped part drops to the ocean floor. (Photo: Lauren Hinkel)

CURWOOD: James J. McCarthy is a Marine Scientist at Harvard University. Thanks so much, Professor.

MCCARTHY: Thank you, Steve.

Host Steve Curwood with Prof. James McCarthy in his Harvard office. (Photo: Lauren Hinkel)

Links

Watch a short video on how the Argo floats work

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth