A Man, His Clarinet and Nature’s Singers

Air Date: Week of October 17, 2014

David Rothenberg is covered in cicadas as he plays along with their collective buzz. (Photo: Charles Lindsay/Courtesy David Rothenberg)

David Rothenberg teaches music and philosophy at the New Jersey Institute of Technology. And he takes his clarinet, and plays along to and with birds, bugs and whales. He talks with Steve Curwood about his music, why creatures sing, and the rare moments of interspecies harmony he’s enjoyed.

Transcript

[MUSIC CLIP WITH CICADAS AND CLARINET]

CURWOOD: David Rothenberg is a philosopher and musician who likes to collaborate when he plays his clarinet, as here, in this track from his latest CD - Cicada Dream band - which features birds, bugs and whales. Now, biologists tell us that creatures sing or call or howl for a reason – to mark their territory, to warn of danger or to attract potential mates. But David Rothenberg, who is a professor at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, thinks that some animals sing simply for the joy of it, and that’s why he likes to play along with them. Professor Rothenberg joins us now from Cold Springs, New York. Welcome to Living on Earth.

ROTHENBERG: Thanks so much for inviting me.

CURWOOD: So growing up what was your personal interaction with nature and its sounds?

Rothenberg played with a Veery thrush and also manipulated the sound by slowing it down. (Photo: Christopher Elliot; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

ROTHENBERG: Well, I grew up in Connecticut, kind of in the suburban countryside, and I was always going outside behind my house into the meadow and by the river and listening to sounds. I was always interested in music and also natural world, and trying to figure out how to connect them.

CURWOOD: So, David, everyone hears the sounds of nature walking through the woods, but not everyone hears music like you do. One example is a little experiment you did with a Veery Thrush song. Let's play the thrush song as you would hear it in the forest.

[VEERY THRUSH SONG AT NORMAL SPEED]

CURWOOD: And then you took that song and slowed it way down.

[VEERY THRUSH SONG AT SLOW SPEED]

CURWOOD: Wow! Who would've known? What did you take away from this little experiment?

ROTHENBERG: I mean, this is one of the most surprising examples of taking a birdsong in its real speed and slowing it down, kind of into the human realm of hearing. And you hear what's already in there, and you hear what the birds are getting. And you kind of grasp how this song can mean so much to the female Veerys that hear it. You know, birds hear five times faster than we do. The Veery on its own is going [WHORLY SOUNDS], and this is kind of a somewhat familiar but strange sound you hear in the woods. To bring it into the human realm, bring the pitch down, this song is an amazing example of the music contained in that little phrase, it really sounds like a jazz trumpet phrase.

David Rothenberg plays his clarinet with a Starling. (Photo: Courtesy Cheetah Television Ltd)

[VEERY THRUSH SONG AT SLOWED DOWN]

ROTHENBERG: [SINGS JAZZ TUNE SIMILAR TO SLOWED VEERY SONG] It's got all the qualities of a good jazz phrase. It's got not only a form and structure, but a real quality of performance and emotion and verve to it somehow; like, if you were playing that it in a lesson with your teacher, they'd say, "Yeah, you got it. You’ve got it figured out."

CURWOOD: Uh-huh. You know, I always thought John Coltrane got his rifts from the Wood Thrush.

ROTHENBERG: Ah! What did he say to that? He probably did.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Now you have a new record out; it's called the "Cicada Dream Band." And there are sounds from cicadas, crickets, whales, but you also have some other musicians on this.

[MUSIC CLIP FROM RECORD]

CURWOOD: How does playing with creatures change when you're joined by other human musicians?

Cicada Dream Band’s album cover. (Photo: Charles Lindsay)

ROTHENBERG: Well, this album came out of the concerts we did when the cicadas were emerging last year, 2013, in the New York metropolitan area, and every 17 years this happens. I had heard that 17 years before, that Pauline Oliveros, the famous experimental composer had done a whole festival of cicadas; so I said, "Let's do it again." So we performed in New York City and in some other places, and in the record we ended up with Pauline playing this kind of digital accordion called a V-accordion along with Timothy Hill, who’s an overtone singer. He specializes in singing—you can sing more than one note at the same time, kind like birds and insects can do. And so we formed this group, and so we kind of based the music, you know, not so didactically like some of my other records have done, but really kind of use it as part of the mix. So we are playing live. I was playing clarinets and also computer, playing some of these sounds, and we were kind of improvising together to form music around the whole possibility that all these sounds are out there in the natural world. And what I hope in this whole process is that my own music and the music of my collaborators—human and from other species—has changed by the encounter, like it leads to something new that we couldn't do on own.

CURWOOD: You've played with different kinds of creatures: birds, whales, cicadas even. So talk about the similarities and differences of playing with those different animals.

ROTHENBERG: Well, the thing is with playing with insects then you are one sound in the midst of millions. It's very humbling to make a little noise in around you. You hear so many individuals altogether forming this kind of collective musical composition where everyone's doing their own little part and somehow it fits together. And although at first it might sound like noise; when you pay closer attention to it you realize there's a lot of organization going on there. With birds you get a sense you're connecting to an individual: an individual is doing something and you're responding to it. And of course it's one thing to take the song, slow it down, make it sound that you interact with, like in the studio or in a concert where you’re playing the recording. That's kind of easy in a way. What's more challenging and kind of daring and surprising is to do it in the wild where you don't know what's going to happen. Like last year I was out in Berlin in late spring playing with nightingales in these parks. Berlin is somehow full of nightingales and they just sing very intensely in the middle of the night.

Rothenberg plays music with many creatures including the Nightingale. (Noel Reynolds; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So how did the nightingales respond to your clarinet?

ROTHENBERG: They kind of keep jamming with you. Scientists have told us there's three ways the nightingale will respond to a sound played to it.

[NIGHTINGALE SINGING]

ROTHENBERG: They will alternate. They will let you do your sound; then they'll do something.

[NIGHTINGALE SINGING AND ALTERNATING CLARINET]

ROTHENBERG: Or they can try and compete with you and jam what you're doing. When alternating, it's a more peaceful sense of, OK, you've got your space; I've got mine. When they're kind of interrupting you constantly it's more like a competitive situation: they're trying to define their territories against yours.

[NIGHTINGALE SINGING AND COMPETING WITH CLARINET]

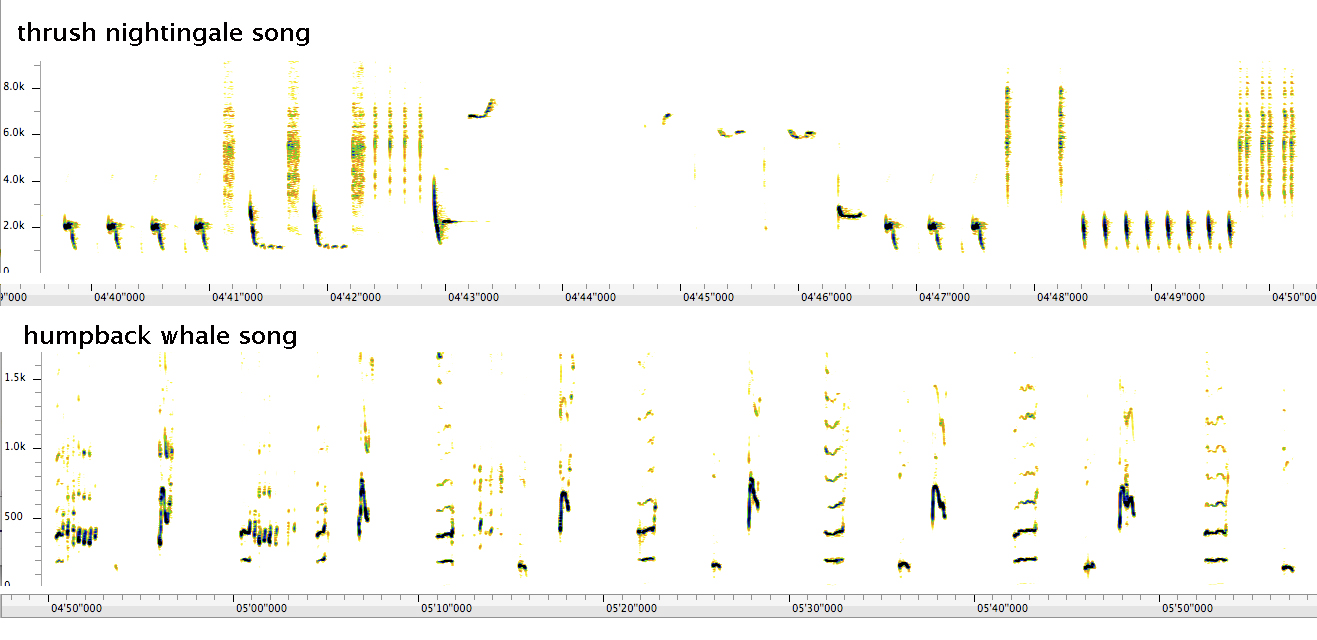

Comparison of the frequency and duration of a nightingale’s song to that of a humpback whale. (Photo: David Rothenberg)

ROTHENBERG: And then finally, the most superior, top nightingales just ignore what you do—maybe they sing, maybe they don't. They couldn't care less.

[NIGHTINGALE SINGING AND IGNORING CLARINET SONG]

ROTHENBERG: This is similar to, say, human jazz musicians—these three types of musicians you will easily meet onstage. Any jazz musician would confirm that.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Well, maybe the jammers are trying to teach you how to play the clarinet a little better.

ROTHENBERG: I'd say sometimes. You know, there's a recent scientific study written by these scientists in Berlin saying that, you know, the nightingales are either playing rhythmic clicks or whistle songs [CLICKING AND WHISTLING], but occasionally they make this sound, which the scientists describe as an "ugly" sound like [MEAH MEAH]. But I listened to it, and all the other musicians we had out there playing with nightingales—it just sounded like a cool bent blue note like a [MEAH MEAH]. And whenever it did it, everyone would smile and laugh because it sounded so cool. It was interesting: the scientists just thought it was unmusical, and all the musicians said it was very musical.

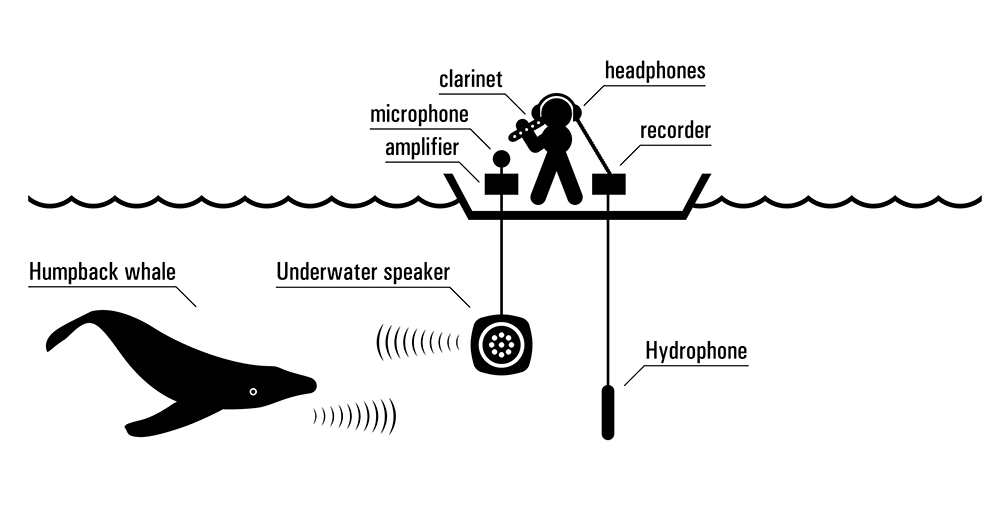

David Rothenberg, headphones on, listens to the sounds of humpback whales and plays along into a microphone. His sound is then transmitted to the whales through an underwater speaker. (Photo: Dan Sythe/Courtesy David Rothenberg)

CURWOOD: So birds like half notes, huh?

ROTHENBERG: They like blue notes like in between the major and minor, like we all do, these in between things that you can't quite define, just like the Veery song has this swinging bluesy quality: ba-da ba-da ba-da. That is surprising ending, but it's just the perfect ending. And every animal that sings is really a world in itself. They all have their own aesthetic sense, something Charles Darwin talked about. Like he wrote in "Descent of Man", birds have a natural aesthetic sense. They appreciate beauty; that's why they've evolved beautiful feathers and beautiful songs. People often forget that. It's not a very common subject to study biology—the aesthetics of evolution—but I'm happy to say more and more scientists are starting to take this more seriously.

CURWOOD: A long time ago, Beatrice Harrison went out with her cello to play with nightingales. What did you think of her music?

ROTHENBERG: Well, what’s so fascinating about that story is this is the first outdoor radio broadcast ever made; so it was a really big deal for the BBC to do this in the 1920s. And they repeated it every year up until World War II; it was a very famous and popular program. And she was confirming just what I was saying: that you can play any sound, the nightingales will join in.

CURWOOD: Let's listen to a little bit of Beatrice Harrison.

[BEATRICE HARRISON CELLO PLAYING DVORAK’S “SONGS MY MOTHER TAUGHT ME” WITH NIGHTINGALE OBBLIGATO]

ROTHENBERG: To listen to this, you really have to put yourself back in mood of the 1920s, when a sound just like that, just as scratchy, was heard as being incredibly realistic, incredibly unique, something utterly new, like a sound recording outdoors mixing humanity and nature. No one had heard anything like that before hearing this. So you just have to say, wow, listen to this; humans can reach across to nature playing a human instrument that birds respond [to] and more than that, this broadcast on shortwave was heard all over the world.

CURWOOD: David, what do you learn about nature, or at least the creature you play with when you do this?

Diagram of David Rothenberg’s setup when he plays with whales underwater. (Photo: David Rothenberg and Martin Pedanik)

ROTHENBERG: You learn that there is music in nature; it's not just a human imposition. It's this aspect of evolution that Charles Darwin was well aware of, but today it's hard to find a biology textbook that admits that evolution creates a lot of weird, cool, beautiful stuff. I wrote a book called "Survival of the Beautiful" just dealing with this aspect of evolution: that evolution produces all this beauty, which is amazing, but you can't always explain it away with some practical purpose. And I think this has profound implications for how we understand nature. The way so many animals communicate is in a way much more like music than like language. They repeat the same phrases over and over and over again, so they're not just saying some specific message like, "Hey, I'm here. I'm hungry. Look at me." They need to say this with the phrases that are shaped and formed, and you find that in all kinds of animal sounds, even in these long songs of humpback whales, the complete song of which takes about 20 minutes to sing. Already in the 1970s, Katie Paine was writing that these songs have a structure, and you could say they have a sense of rhyme at the end of a long phrase. They come to the same sound. And they'll sing something different, and it'll come to the same ending – a sound like [SCREECH] at the end of a long phrase.

CURWOOD: OK, you listen to the animals, and you play along. So to what extent do they listen?

ROTHENBERG: Well, that's a good question. We can study the hearing apparatus of different animals so we know what kinds of frequencies they hear, but it's harder to know what's going on in their minds. Birds have been the most studied in this regard. You can tell what goes on inside the brain of a songbird. Certain areas light up when certain sounds are played or sung. They do respond to certain kinds of things. What's so fascinating with insects is that many of them make sounds they can't even hear. Why does that happen?

CURWOOD: And the answer is?

ROTHENBERG: We don't know. Much of this is just not known. The notion that animals are making music has been understood by humans for thousands of years. Musicians have thought about it. Scientists have thought about it, but they debate whether it's a useful way to think about nature in a scientific way. Is it just a human subjective imposition or is it a useful way to analyze that?

CURWOOD: Let’s listen to another clip now. This is from your record Whale Music. The tune is called "Never Satisfied".

Humpback whale glides by. (Photo: Courtesy Tomawak Productions)

[WHALE SOUNDS WITH CLARINET]

CURWOOD: What was it like playing with the whales? Where were you? When was it? How long did it go on?

ROTHENBERG: It's not so easy to play clarinet along with humpback whales. One reason is that they're underwater and I was sitting on a boat wearing headphones. You can't tell where the sound is underwater; there's no sense of space. It's just everywhere around. It's ether louder, nearer or quieter, further. So this whale was right under the boat. You could almost hear him without the headphones at all. And what's interesting about humpback whales is they’re always changing their song, always listening for new sounds, and it makes it interesting to play with them because sometimes, only sometimes, they respond to what I'm doing. I have to say I have done this for many hours, and most of the whales seem to ignore me, no surprise. But in this one example I showed you, you can really hear that as the clarinet plays a steady note [MIMICKS CLARINET NOTE], then the whale actually tries to go [WHALE MIMICKS NOTE]. He tries to sing in a more steady way than he usually does.

A Humpback whale breaches. (Photo: Courtesy Tomawak Productions)

[WHALE SONG WITH CLARINET]

ROTHENBERG: Whales don't usually sing horizontal steady sounds. They're usually more going [UP NOTE] or [DOWN NOTE], they go up and down like that. And so this is a kind of surprising moment where the whale showed some interest. And so, at that moment, you feel like, ah, maybe something's going on here—maybe there's a sense of getting through to another species through music.

[WHALE SONG WITH CLARINET]

CURWOOD: David Rothenberg is a musician, author and professor of Music and Philosophy at the New Jersey Institute of Technology. Thanks so much, Professor, for taking this time.

ROTHENBERG: Thanks a lot.

[WHALE SONG WITH CLARINET AND CICADAS WITH CLARINET]

Links

David Rothenberg’s story in the New York Times about playing with whales

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth