Fascinating & Toxic - Traditional Moroccan Tanneries

Air Date: Week of October 31, 2014

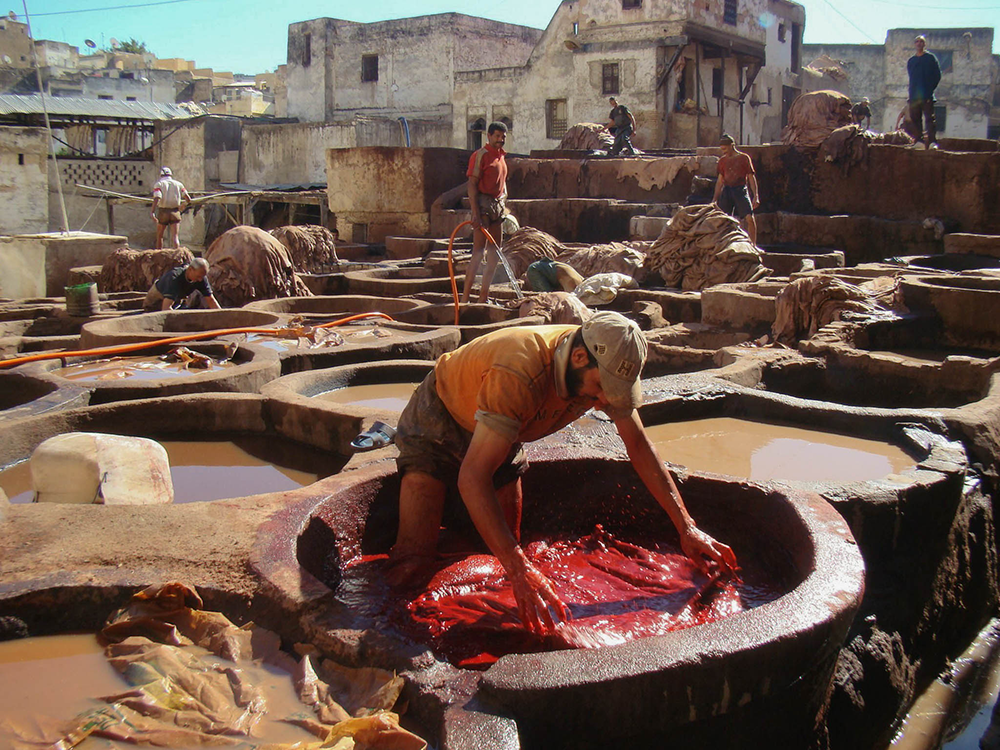

Exposure to toxic chemicals is nothing new when it comes to being a tannery leather worker. It is a job that is highly labor intensive and only pays between $2-5 USD a day based on skill level and production output. This is Chouara Tannery, a traditional tannery located inside the medina of Fez, Morocco. (Photo: Julian Harris)

Colorful leather goods are popular tourist souvenirs from traditional tanneries in Morocco. But workers must stand in toxic, chromium laden waters every day there to soften and dye the hides, and prolonged chrome exposure and lax disposal of waste tannery water can cause serious health and environmental problems. But as Amulya Shankar reports from Fez, modern tanning techniques can help mitigate these issues and maintain some of the old-world charm.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Off on vacation now to Morocco. A million people visit this North African kingdom every year, making tourism its second biggest industry after phosphate mining. Visitors flock to the one-time capital, Fez, and wander in the old medina, a walled city-within-a-city where artisans in small shops work and offer their clothing, jewelry and brightly colored leather goods for sale. The tanneries, in operation in Fez since the 14th century, are the biggest draw. But though leather-working is picturesque, there’s a darker side. Reporter Amulya Shankar has our story from the traditional Chouara Tannery.

[TOURISTS CHATTING]

SHANKAR: The stench is overpowering. I’m part of a tour group that has climbed steep steps to the rooftop of the Chouara Tannery shop. Right away, we are greeted with the smell of wet animal skins from the dye vats several stories below. As we peer down, we see hundreds of vats that cover an area the size of a football field. Men stand thigh-deep in murky water, sloshing hides back and forth to soften and color the skins. A sprig of mint we’ve been given is supposed to combat the stink. Sniffing the mint helps, but not much.

REHACK: It’s like visually exactly what you think Fez is going to be, so you can definitely feel like it’s there for you, for the tourist.

SHANKAR: That's Hannah Rehack, an American student studying in Morocco and touring Fez. She’s right. These men stand in cold, chemical-laden water, handling animal skins, all day, every day of their lives, to entertain the tourists who will buy the goods they help produce.

The amount of waste generated by tanneries is staggering. Chemicals, bacteria, and animal by-products are regularly dumped into the Sabou and Fez Rivers. (Photo: Julian Harris)

[SHARPENING KNIVES]

SHANKAR: Two hundred men work at the Chouara tannery in the ancient city of Fez. Some of them scrape the hair from the skins using razor-sharp knives. Once the scrapers are finished, the skins are dumped into the vats where others take over the softening, dying process. The work never stops, the noise never ceases, and the air is filled with the pungent smell of wet animal hides.

[WATER SPLASHING]

SHANKAR: But it’s the water that’s the main problem. Chromium has been a major ingredient in the tanning process since the 1800s. Its unique properties produce versatile leather that can be used for making saddles, sturdy shoes and suede jackets. Chrome-tanned leather handles high temperatures, absorbs less water, and dyes more easily. But chrome is also a known carcinogen, and the water in the vats is loaded with the chemical. Not a good thing for the men who spend their days up to their thighs in it.

SHANKAR: Abdul Kadhr, who is 32, has been working at the tannery for 16 years.

KADHR: [SPEAKING IN ARABIC]

SHANKAR: Kadhr claims he has had no health effects from his work in the tannery. Perhaps he’s been lucky. According to the World Health Organization, those who work in close contact with chromium can suffer from immune system and respiratory problems.

Tanner Abudul Kadhr said, “I am married and I have kids and I work for myself and my family and thanks to Allah I make enough for myself and my family…This job is good for the health…only natural dyes are used, it is not toxic…people work until they are 80 sometimes and are in good health.” However, there are studies that dispute this and actually state that this job is linked to immune and respiratory illnesses. (Photo: Julian Harris)

SHANKAR: And there are heath concerns beyond the risks for tannery workers. About every 25 days, the dyes lose their potency and need to be refreshed. So chemical-laden water from hundreds of vats is dumped into the Fez River every month.

Ismail Aloui is with the Agency for the Development and Rehabilitation of Fez. He says chromium contaminates the city's food supply and sickens people.

ALOUI: They suffer directly. It’s a health problem, daily problem.

SHANKAR: An official at the water department in Fez, Mohammed Meziani, admits that chromium and other chemicals are fouling the water but he argues that the city’s drinking water is unaffected.

MEZIANI: We know the chromium is toxic. But it’s downstream. The water we drink is from upstream.

SHANKAR: Steven Lange is a U.S. expert on tanning. He directs the Leather Research Laboratory at the University of Cincinnati. He says 80 to 90 percent of tanneries worldwide still use chrome, but modern tanneries have high safety standards. Lange says the difference lies in the controls.

Tanner and salesman Abdul El-Machour stated, “I was born like 70 or 80 meters from the tannery and I started to come to the tannery when I was like four or five years old, not for work, but for playing…When I was 8 years old, I do very bad accident…I fell from tannery terrace into the vats.” (Photo: Julian Harris)

LANGE: We do want to make sure that our industry doesn’t have a negative impact on the environment. In the US, we have the strict laws, and all the tanneries here, they have their processes controlled. Modern tanneries now will have water collection systems to minimize water usage and to reclaim the water and reuse the water. They will have a process in place to capture any leftover chrome from the wash processes, to recycle it and use it again.

SHANKAR: Tanneries in developing countries have a long way to go to meet health and environmental safety standards that are the norm in the developed world. But even in Morocco there are new tanneries, not far from the old ones, that provide safer alternatives.

[MACHINERY IN THE TANNERY]

SHANKAR: 55 modern tanneries outside the old city of Fez use high tech filtering systems to produce less pollution, and they are much safer for the environment. Mohammed Behara owns the modern Saiss Tannery in an industrial complex on the outskirts of Fez.

BEHARA: [SPEAKING IN ARABIC]

Three traditional tanneries in the medina of Fez (including Chouara) practice traditional methods of washing, smoothing and coloring animal skins to produce soft leather goods. (Photo: Julian Harris)

SHANKAR: Behara acknowledges that new facilities like his don't project the air of romance that the historic operations offer. His tannery does not have a shop, and they don’t attract visitors. The business model is different. The leather tanned here is shipped to artisans in cities all across Morocco. While the old tanneries are about producing leather goods for tourism, the modern tanneries focus on the tanning process.

And today that process includes an awareness of environmental issues. For instance, they cluster the tanneries close together so all the water can be collected and treated centrally. Steven Lange says it’s a smart strategy that can save more than just money.

LANGE: The whole idea is to, not just to reduce the chrome effluent, but effluent overall and reduce the water usage. Water’s becoming a very expensive commodity, and we know there’s a limited supply, and you want to preserve that as much as possible.

SHANKAR: Back at the Chouara Tannery, our tour group heads to the terrace shop, one of many that stop here to see the results of the labors going on below. Bags, slippers, and jackets of every color burst from the shelves as shopkeeper Abdul El-Machour shows off his wares to dozens of eager visitors. It’s no surprise that a single shop can make $1,200 to $1,800 a day during the summer.

American student Franny Krieger says she loved the aesthetic of the leather despite the pushy sales pitches.

KRIEGER: It’s beautiful … it’s a buyer’s paradise in there, and they really do try to get you to get you to buy something.

Abudulhay Sadaq, 23, was an apprentice tanner since he was 13 years old. “When I was very small, like 4 years old, I loved my father’s job…and everyday I would go from the school to the tannery…I hope they will bring me back to the school to get a good mind, but I am a little too old to study now,” he said. (Photo: Julian Harris)

SHANKAR: Shopkeeper El-Machour says that the old tanneries are a vital part of Morocco’s tourism industry.

EL-MACHOUR: Now Morocco is like a famous country in the world… it’s important for the economy of medina and it’s important for the tourism also. I think the tannery stays forever.

[KNIVES SHARPENING, WATER SPLASHING, WORKERS TALKING]

SHANKAR: Eventually polluted water and contaminated land, not to mention workers’ health, will have to be addressed. And Steven Lange argues new, creative approaches could be used to preserve some of the magic that tourists are looking for. Maybe the old tanneries could be re-plumbed so that the effluent could be carried away safely without compromising the historical aesthetic.

LANGE: Could it be they could do something like what Disney does, you know, have it look like it’s old, but actually using modern technology in the background?

SHANKAR: Whether tourists – and the traditional tanneries – would accept this Disneyfication is another matter. For now, watching leather being made in the traditional way, taking home the beautiful products, and even enduring the smells of the tanning process is what visitors have come to expect. But for the citizens of Fez and their environmental advocates, change has to come. Their health, and the health of their land and water depend on it.

For Living on Earth, I’m Amulya Shankar in the old medina of Fez, Morocco.

CURWOOD: Thanks for that story to Round Earth Media, SIT Study Abroad, and reporter Oumayma Sbila. There are photographs and more at our website, where you can hear our program anytime, or download the audio. The address is LOE.org. That's LOE.org.

Links

WHO reports on Chromium's negative health effects

WHO Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality, concerning chromium

The Agency for the Development and Rehabilitation of the city of Fez (ADER-Fès)

The Choura Tannery’s Trip Advisor page

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth