Quiet Places Around the World

Air Date: Week of December 12, 2014

The Kelso sand dunes of the Mojave Desert. (Photo: Courtesy of Trevor Cox)

Trevor Cox, a professor of acoustic engineering at the University of Salford in the UK, explores the world looking for its most interesting sounds and wrote about them in The Sound Book. But he also considers silence and tells host Steve Curwood about the uncomfortable effect of a totally dead room, the natural silence of the Mojave desert and the importance of preserving quiet places to our well-being.

Transcript

[MUMBLED TUNE]

CURWOOD: Now, that sounds something like Rossini’s William Tell Overture played, well, somewhat out of tune. But it’s actually highway rumble strips in Lancaster, California, recorded by Trevor Cox as part of his research for “The Sound Book”. Trevor Cox is a Professor of Acoustic Engineering at the University of Salford in England, and he travels the world in search of beautiful or surprising sounds. But for one chapter, he takes off his headphones and explores silence. Trevor Cox joins us now from the UK. Welcome to Living on Earth.

COX: Hi, there.

CURWOOD: So, you're out in the Mojave, and you're listening. How do you feel in this experience?

COX: Well, it was kind of an odd experience because we had gone there to hear booming sand dunes. We had to go in the middle of the summer, in the middle of June, so it was very hot, and we were actually high up on Kelso Dunes, which is also quite hard to walk up. Even when you just walk on it, you can actually hear, well, it sounds a lot like someone playing the tuba badly as you walk along, so you can actually hear your footsteps making these weird sort of baap, baap, baap, baap..

[SOUNDS RECORDED ON THE DUNES].

Recording the “droning sand dunes” in the Mojave Desert’s Kelso Dunes. These are not the only dunes that make this noise, but it only occurs when grains of sand are the same size and tumble over each other at the same rate. (Photo: Courtesy of Trevor Cox)

COX: So, I suppose one of my feelings was vague exhaustion and heat, but beyond that I thought of it as a beautiful silence because it really did seem very natural for a desert not to have any sound. I mean, if I had been somewhere...if I had gone to the normal countryside and heard silence, I might have felt, well, where's the wildlife…it all sounds a bit dead. But in the desert, you don't expect to hear anything, so it seemed quite natural.

CURWOOD: So, the reason you went to the desert in the first place was to capture very big sound, that sound of the famous singing sands. Let's hear that.

[BOOMING SANDS SOUND]

CURWOOD: It almost sounds like the sand is alive is some way. Tell us about the moment when you first heard the sound in person.

COX: Yeah, you talked about the dune sounding alive. Well, it feels alive because to create it, if there's no spontaneous avalanche happening, what you need to do is to sit on your backside and create an avalalanche yourself. So, when you hear that sound, what I think about is not just the sound, but the memories of the whole dune shaking around me as the whole lot of sand went down underneath me. There's a lot of debate of about why it particularly makes that sound, but it's all to do with the friction of the grains as they move past each other, with grains all the same size, they slip over each other at exactly the same rate.

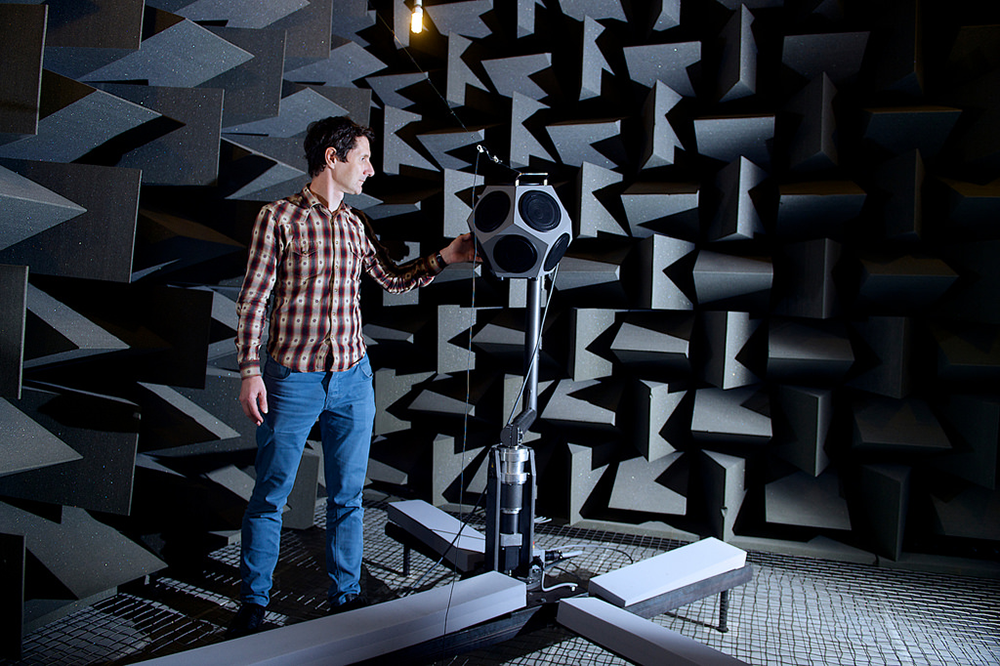

CURWOOD: Now, you have a place that's made to be completely silent at the University of Salford, an anechoic chamber. Tell us about the chamber and how it can keep out all the noise.

COX: It's a very strange place to enter into. You have to go through these very thick heavy acoustic doors, which are there to shut out the outside world. When you arrive in it, in ours you have a trampoline wire floor you stand on, which is a bit disconcerting, and then all around you're surrounded by these big gray wedges on the floor, on the walls, on the ceiling. Everything you say just disappears into the wall and vanishes so when you talk it sounds odd because it's quite a lot of effort and everything sounds a bit muffled. I was going to say the nearest description is if you're in a plane and you know your ears need to pop, and then if you stop for a moment, you notice you can't hear any outside sounds because you're inside - essentially you're inside a room within a room - and it's all mounted on springs to stop any vibration from getting into it, so it's an incredibly quiet space.

Trevor Cox stands in the University of Salford’s anechoic chamber. (Photo: Courtesy of Trevor Cox)

CURWOOD: So, let's get an idea of what it sounds like to be in there. We're listening to a little bit of you playing Claude Debussy's Syrinx on your saxophone in the chamber.

[SAX INSTRUMENTAL]

CURWOOD: So now why does that sound so different than in the concert hall or someplace that's not so dead?

COX: Well, normally in a concert hall, whenever you stop in there, the sound lingers in the room for a little while. In a concert hall, it lasts probably a couple of seconds before dying away, and even, I'm talking to you from a little office here, it will last maybe half a second before dying away, whereas in that place there's nothing, there's no reflections off the walls, there's no reflections off the ceiling, or a floor to make the sound linger, so everything just dies immediately. So it's very unnatural. As a player, one of the things I noticed is my vibrato doesn't very good and all the little details of my playing which aren't quite right are really really clear. So, musicians don't really like playing in that because there's no support from the room, it feels like really hard work, and all your mistakes are kind of highlighted.

CURWOOD: That's right. You know, every vocalist's trick for performance is a little echo, a little reverb on there. It makes them sound sweeter and better.

COX: Yeah, and even if we're not professional vocalists, we like to go into the bathroom and sing because we know the supporting effect of the tiled walls make it sound better.

CURWOOD: Let's play another clip from the chamber. This one is of you firing a starting pistol.

[SOUND OF A CLICK]

CURWOOD: I'm going to play that again because I can barely hear that.

[SOUND OF A CLICK]

CURWOOD: Now, we're going to play you firing that starting pistol out in the real world.

[SOUND OF A GUNSHOT]

CURWOOD: So this is really a surprising example of how much the chamber can take a huge sound like a gunshot and turn it into a helpless little pop.

COX: Yeah, it's just a little click isn't it? Yeah, because we're used to hearing a gun, I suppose we're used to hearing a lot of Hollywood guns for one thing aren't we? Which have got lots of extra reverberation on that, lots of room effect to make them sound powerful. Whereas, in reality, the gun itself really just makes a little click. When I made that recording, I actually went back and thought, "No, that can't be right. I have to do it again," because I couldn't quite believe how quiet and how pathetic it was really.

Professor Cox fires a starting pistol in Bridgewater Hall in Manchester for a class of University of Salford students. (Photo: Courtesy of Trevor Cox)

CURWOOD: Unless, of course, you're a spy and you want a silencer on that gun, doing somebody in.

COX: I guess so. I suppose it's an ideal place for assassination. I never really thought of that before.

CURWOOD: What did you take away from thinking about and visiting the silent places like the Mojave?

COX: Well, it made me think about how there's different kinds of silences. I mean, strictly speaking, silence is an absence of sound. But you don't usually hear that, and the reason is that actually you make internal noises. So, if you go into an anechoic chamber like the one we have at Salford, what you'll hear is actually the sound of blood moving in your head, or you might here some firings on your auditory nerves. So you don't tend to find complete silence, that's one of the surprises, but if you travel around you find that for a lot of people, peace and quiet is not about getting into complete silence places which is after all, rather desolate, but actually places where manmade noise is absent. What you then have is a lot of natural sound.

CURWOOD: Now, the Campaign for Rural England is one group that's working to identify the most tranquil places in England and had you record a few of them. Let's listen to a little bit of what they call the most tranquil place.

[SILENCE, WITH SOUND OF TAPE HISS]

CURWOOD: Well, it's not completely quiet, what are we hearing here exactly?

COX: Well, the hissing you're hearing is actually the electrical noise on my recorder. And I had some recording equipment, I tried to record it. But I had to turn the gain up on my amplifier as much as I could and what you'll hear is a little bit of electrical hissing. It's quite hard to get to, so I didn't have the quietest of recording gear because it's tranquil, it's away from manmade places. It's not near any roads. And, in fact, to get there, I had to bike on the road, mountain bike across the country, and then go for a hike to get to the actual spot they identified. So it's quite a long palaver to get to the place. And there, there really wasn't anything to hear. I mean, it was quite, quite surprising. I was expecting to maybe hear some nature, but it really was almost completely silent. There was occasional bird sound, but it was very rare.

CURWOOD: And Trevor, where is this place?

COX: Well, it's kind of kept a little bit secret. If you look at a map of Britain, it's about about three-quarters of the way up, so it's right at the corner of England and Scotland and Northumberland And it's quite a funny place when you go visit it, because when you go towards it, what you'll actually find is, it's right near a Royal Air Force firing range. And one of the reasons it's very quiet is because it's the Air Force training. There's nothing else around because it's normally used for shooting practice. But if you turn up there on the day they're all there practicing, I can assure you it is anything but tranquil.

CURWOOD: Now, what other kinds of attempts to protect these quiet places are already in place, legislatively or otherwise?

A view from the most tranquil place in Britain, near the border of England and Scotland. (Photo: Courtesy of Trevor Cox)

COX: Within Europe, they actually have a directive to say that countries have to identify quiet areas and identify actions they will take to preserve them. Now, I know across America, the National Park Service look to try and preserve soundscapes, so not just preserve the landscape - what you can see - but also preserve the sounds that you can hear in places. So there's quite a lot of campaign groups and regulation trying to deal with this problem of noise. It's quite a difficult balance to strive because most human activity makes noise and because we don't want to stop people doing what they want to do.

CURWOOD: Now, how are silent or at the very least quiet places at risk?

COX: Well, they're at risk in the cities and out in the countryside, so out in the countryside we have problems like aircraft overflying. In cities, we have a problem that the city itself on average isn't really getting very much louder, but what's happening is we're losing little quiet pockets, little places where you can get away from the noise.

CURWOOD: What about aircraft...it seems that any time I'm in the wilderness someplace that seems far and away and early in the morning, extremely quiet...then the planes.

[PLANES FLYING OVERHEAD]

COX: Yes, the thing is, engineers are doing quite well at making planes and cars quieter, but we're flying more, we're driving more. So what's happening is individual planes and cars are getting quieter as technology gets better, but there's many more people using them. Especially in a plane, because you're high up in the air, it pollutes a very large area, so, yeah, there is a problem in lots of countries about the noise from aircraft. At the moment in the UK, they're debating where to build another runway near London, and all discussions are nearly all about the noise problems this creates.

CURWOOD: Well, why are these quiet places so important and why should be concerned about losing them?

COX: There's lots of evidence that noise causes us problems. We know that noise getting in the way of sleep is a problem, so we know that it's important that we can get away from noise, and psychologically that's important for us as well. There's been a variety of scientific studies into the importance of having quiet refuges, and for example, there was a study in Sweden, which showed that if you lived on a busy road then that was OK provided that one side of your house backed onto somewhere quiet because that gives you somewhere in your house to get away from the noise for some of the time. So provided people can get away from the noise of the city and they're not stuck listing to noise all time, they seem to find it much less annoying.

CURWOOD: Now, what about being around people who are constantly chattering?

Trevor Cox is a professor of acoustic engineering at the University of Salford. (Photo: Courtesy of Trevor Cox)

COX: Well, I think it's quite interesting because there's something quite pleasurable about chattering provided it's not too much, because we're social animals, we do very well because we live in a society where we corporate with each other. So, actually the sound of gentle babble you get as you sit in the corner of a cafe, I suspect is rather good for you.

[SOUNDS OF CHATTER IN A QUIET CAFÉ]

CURWOOD: So what got you into sound?

COX: Well, I did physics originally. I was good at science as a kid and I was also a musician. I played the clarinet when I was younger, and so it seemed a natural way of combining two things, my interest in music and my interest in science.

CURWOOD: And so, all those hours sitting with a clarinet have paid off?

COX: Well, I don't know if they paid off. I'm not the greatest of musicians, but they certainly inspired an interest that lasted the rest of my adult life.

CURWOOD: Trevor Cox is a Professor of Acoustic Engineering at the University of Salford in the UK. Thanks so much for joining us.

COX: Thanks very much.

[SAXPHONE CROONING]

Links

The Sound Book by Professor Trevor Cox

Cox’s “sound tourism” blog highlights strange and interesting sounds all over the world.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth