Training Your Brain to Crave Healthy Foods

Air Date: Week of January 16, 2015

A new study involving MRI brain scans suggests that nutritious dieting can shift cravings towards healthier foods. Tufts Professor of Nutrition and Psychiatry Susan Roberts tells Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer about the findings and how food interacts with the brain.

Transcript

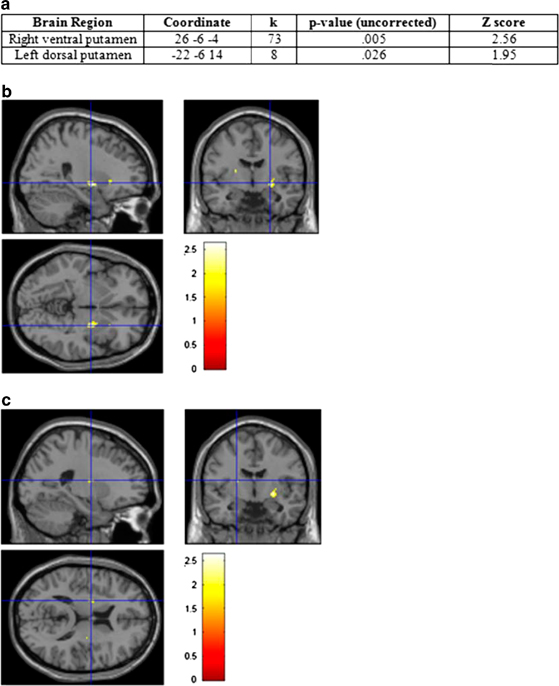

CURWOOD: Now a fair amount of food waste comes when affluent consumers buy healthy foods they should eat, but then leave them to molder in the fridge in favor of high fat and sugared junk food. Let’s face it, junk food can be addictive and hard to kick. But a recent study in the journal Nutrition & Diabetes suggests that it’s possible to retrain the brain to crave healthier options, by using a strategy called cognitive restructuring. For the study, researchers randomly assigned overweight or obese people to either a control group or a weight-loss intervention group, which met regularly and was provided a high-fiber, high-protein diet. After six months, an MRI showed the intervention group had an increased brain response to healthy protein and fiber-rich foods, and less response to high-calorie junk foods. To find out more, we called up a study co-author, Professor Susan Roberts of the Nutrition School at Tufts University. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Researchers showed participants images of ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ foods while in an MRI. The scientists then compared brain activities between the groups. (Photo: Courtesy of Susan Roberts)

PALMER: So can you give me a short description of your study and what its results were in terms of dieting?

ROBERTS: What we have is the first demonstration that it's really possible to rewire people's brains so that they learn to like healthy food and that they're less tempted by junk food. We did some baseline brain scans and then we randomized people to what we called a weighted-listed control, or to our own weight loss intervention and then six months later we remeasured them, and we were looking at changes in the brains’ addition centers to see how much they were lighting up for different kinds of foods.

PALMER: And what did you find when you look at the brain scans?

ROBERTS: So, we showed people a bunch of pictures, and some of the pictures were of healthy food. There was green salads, grilled chicken, all the things that people know are healthy. And then, there was also things like french fries, big deluxe chocolates and fried chicken, things that everybody knows it's not good to eat too much of. And we were looking for their brains’ response to these pictures. What you're doing is you're looking for the amount of neuronal activity in this rewards center. This was a study about what tempts people, and the results are really quite amazing. They really were less tempted for things like fried chicken, and more tempted for grilled chicken after they'd been through the intervention compared to our weight-listed people who got nothing.

PALMER: Now, you call this cognitive restructuring. What exactly are you doing?

The iDiet, which was developed by Dr. Susan Roberts and used in the study, includes recipes for Tanzanian Chicken Kebabs, using ingredients found in most supermarkets. (Photo: Courtesy of the iDiet)

ROBERTS: So, cognitive restructuring is the process of changing your brain. When you see a brain scan that has somebody lighting up less for junk food and lighting up more for healthy food, what you've done is you've changed the pathways in the brain. You've effectively put some of those pathways connected to junk food to sleep, and you've rewired some other pieces so the healthy pathway is more active.

PALMER: But surely that means that if you happen to pass a donut shop and say, "Oooh, I really feel like a donut or I'm really feeling hungry, I'll just have one of those,” could you backslide into the old junk food ways?

ROBERTS: You could definitely backslide. I mean, the power of this approach is that people say they're less tempted, and so they're less likely to stop for that donut. But, you know, you can regrow those craving circuits for donuts. It's not like we've killed the circuits. I think we've put them to sleep. And so, there's a certain amount of care if you'd like not to get casual and eat the things you're no longer craving just because they're around in order to maintain this new and kind of healthier way of eating.

Diets high fiber help people feel full and satisfied after a meal. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

PALMER: I'm interested if there are lots of different possible circuits or if there's one circuit and what you've done is change the one circuit.

ROBERTS: There's a ton of different circuits. There's a circuit roughly speaking for every food.

PALMER: Oh, really. So it's just of matter of which circuits light up?

ROBERS: Well, I think eating healthy food when you're hungry is one of the most important things people can do on their own. Because hunger is a very important way to kind of push those pathways in the right direction.

PALMER: So tell me a little about the intervention. What did it entail?

ROBERTS: So, first of all, a disclosure. I think this is a really advance in obesity and treatment, and as a scientist I can't possibly scale this to make this available to millions of people. So I have given the program to a company, but what it is, we have our own unique dietary composition. We have menus that we get people to follow while they learn how to do the new program. We've designed the menus so they have a ton of choices. We have pizza. We have hot dogs. We have steak. We have ice cream sundaes. And some of them come when recipes, and but of them are just instruction meals where you buy the right stuff in the supermarket and you put it together. And the brain training happens as a result of eating the right things and not eating the wrong things.

Dr. Roberts says that including high-fiber, low-glycemic index versions of familiar foods in a dieting program helps dieters lose weight. (Photo: Courtesy of the iDiet)

PALMER: So, if you're allowing people to eat pizza and eat burgers and eat hot dogs, there's got to be a very strict kind of portion control behind this as well.

ROBERTS: Well, portion control is part of it, but the composition of these foods is very different. It's a fairly high-protein diet; it's a low-glycemic index diet. It's a very high fiber diet. So they can have pizza, but it's my own formulation, which has more fiber and more protein and less carbs, for example. So that's one of the ways we get rid of the cravings is that we give people a taste they like, but the composition is about a composition for control and cravings.

Dr. Susan Roberts is a Professor of Nutrition and Psychiatry at Tufts University and creator of the iDiet. (Photo: Courtesy of Susan Roberts)

PALMER: But you're suggesting that a particularly high fiber diet, which is not necessarily what's to be found out there unless you're shopping very carefully...

ROBERTS: I think shopping carefully is definitely part of it. There's tons of good, high-fiber low-carb breads, crackers, pastas, even soups. All of the foods that you could want for a healthy weight regulation are out there today. Careful shopping is actually what it comes down to. You can't just go back to exactly what you were doing before because what you were doing before caused you to gain weight. So there's some long term changes that need to be made. But I think what we're going is getting people to enjoy those long-term changes so they don't feel that deprivation.

CURWOOD: Susan Roberts, author of The “I” Diet, and Professor of Nutrition and Psychiatry at Tufts University spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Links

The original study published in Nutrition & Diabetes

The iDiet, developed by Dr. Susan Roberts based around this research

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth