New Orleans Still Vulnerable To Storms

Air Date: Week of August 28, 2015

Aerial view of 17th Street Canal Breach looking east. Katrina damaged 169 miles of the 350-mile-long levee system protecting New Orleans. (Photo: EPA)

Hurricane Katrina drowned New Orleans ten years ago, even though that storm was weaker than other hurricanes the city had survived before. Years of wetlands loss amplified the storm surge and the levees collapsed under the weight of engineering errors and poor maintenance. Hurricane expert Ivor van Heerden warned of the dangers in 2001, and tells host Steve Curwood that despite repairs, the city is still at risk.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Ten years ago Katrina was one of the most powerful hurricanes ever recorded in the Northern Gulf of Mexico, but by the time it skirted past New Orleans to hammer the Mississippi coast, the storm was much weaker. But unfortunately, the defenses protecting New Orleans from sea were also weaker than necessary. Many of the wetlands that had blunted worse storm-surges in the past were gone, and too many pumps and levees broke down, thanks to poor design, flawed construction and lax maintenance. Katrina inundated New Orleans as it passed, and left a city and nation in shock.

Ivor van Heerden sounded the alarm about the potential for catastrophe back in 2001 when he was a hurricane expert at Louisiana State University. He joins us now for a look at what’s changed - and what hasn’t - since. Ivor, welcome back to Living on Earth.

VAN HEERDEN: Well, thank you very much for the invitation.

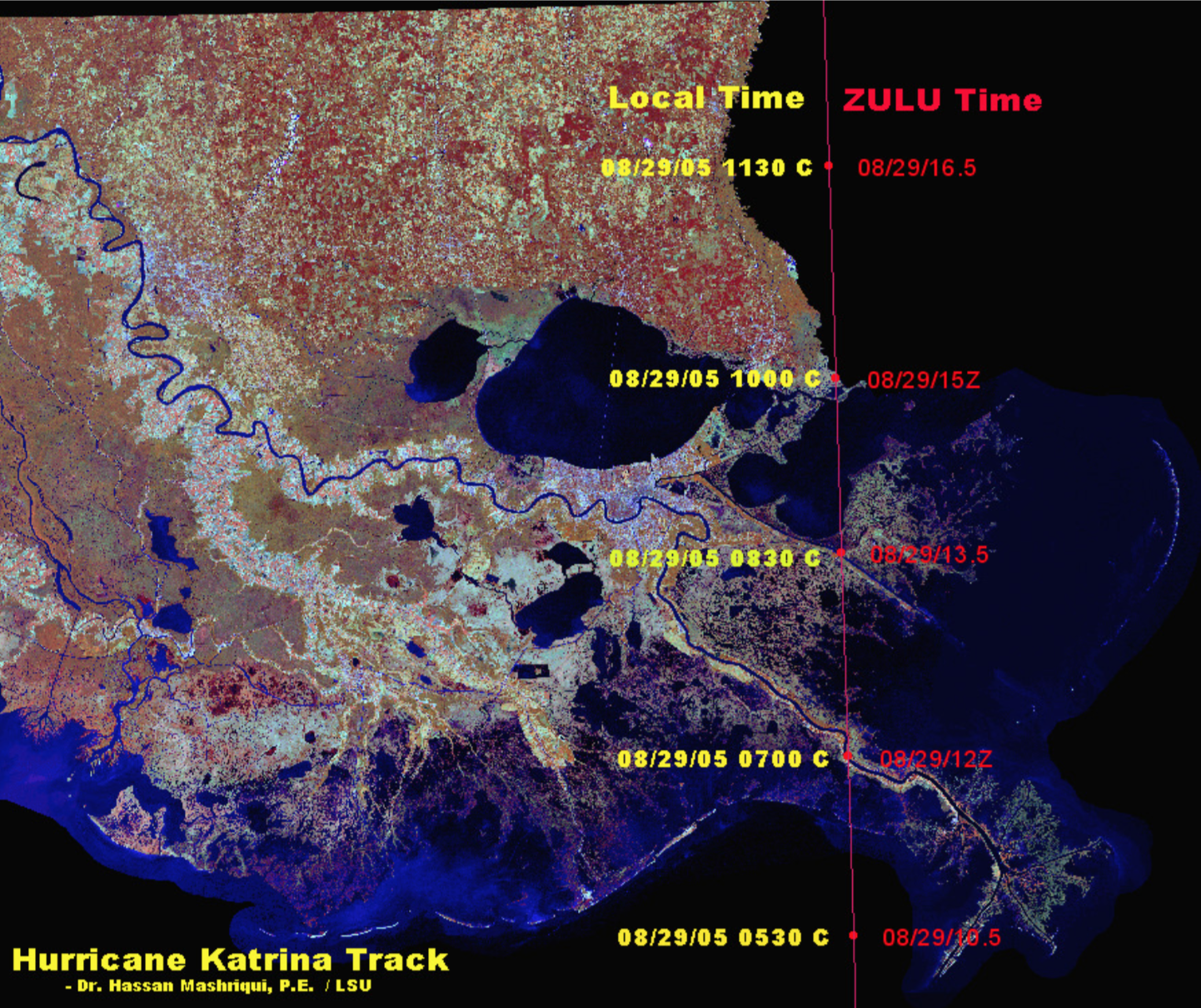

Hurricane Katrina’s storm track. Katrina first made landfall in coastal Louisiana, her eye skirting New Orleans by about 40 miles before the hurricane made a second landfall in Mississippi, devastating the city of Biloxi. (Photo: courtesy of Ivor van Heerden)

CURWOOD: So first of all, just remind us of the scale of the devastation in New Orleans and in Southern Louisiana as a result of Hurricane Katrina. How bad was it?

VAN HEERDEN: Well, over half the 350 miles of levees failed, and as result you add in some places walls of water 18 foot high sweeping through the homes. The three different bowls of New Orleans were flooded in most cases right up to the eaves of the home, so we talking about 500,000 people being displaced. I often point out to folks just imagine if you were sitting in your den this evening and tomorrow it was gone, your cars were gone, your home was gone, your job was gone, everything was gone. That was the enormity of this catastrophe.

CURWOOD: Now how did engineering failures contribute to the devastation in the region caused by Katrina?

VAN HEERDEN: Well, if the levees had held we wouldn't be talking about Katrina in Louisiana, we would be talking about Katrina and the devastation on the Mississippi coast because the storm actually made land fall in Mississippi, not Louisiana. With a storm like Katrina, there might have been a little bit of water overtopping of levees but certainly the pumps would've been able to deal with it. But the levees...people in New Orleans had been led to believe would protect them from such a storm just literally collapsed and the earliest term we could come up with was“catastrophic structural failure”. Because the levees where ill-designed, the wrong science was used and so on, we ended up with many levee systems four to six feet too low. Katrina might've been the trigger, but this was a man-made catastrophe.

CURWOOD: Now, how did wetlands loss in southern Louisiana impact the flooding in New Orleans and surrounding areas?

The storm surge left dunes, comprised of sand from the barrier islands, up to six feet thick in a neighborhood near the Mirabeau Breach on the London Avenue Canal. (Photo: courtesy of Ivor van Heerden)

VAN HEERDEN: We've lost in Louisiana a millions acres of our coastal wetlands. In many places there used to be cypress swamps, in others a rather healthy marsh. Just the presence of the vegetation removes energy from the wind and then you get less surge and then of course the surge, as it moves through and over the vegetation loses a lot of its elevation due to the friction. If we had healthy wetlands, we wouldn't need as high a levee system and so on. Because of the activities of the Army Corps of Engineers in putting up the levees and closing tributaries, we've stopped the overbank flooding and the distribution of fresh water sediments and nutrients into the wetlands. We've been starving our wetlands and then to add insult to injury we came along and cut them up for the oil and gas industry. The sad reality in some ways is that the land, the coastal land in Louisiana, subsides about three feet every hundred years. Now, if you add to that the predictions for sea level rise you’re talking about an effective rise in water of six feet over 100 years. So it's a losing situation unless you go in and try and restore the wetlands.

CURWOOD: So in your view what's the most realistic scenario to protect New Orleans and nearby Louisiana from another devastating storm? What advice do you think the Dutch might have for us? They've been protecting low-lying areas for years from the seas.

VAN HEERDEN: Well, the Dutch, they had their Katrina in 1957, and what they recognized was they had to retreat from some of the low-lying areas and then build a line of defense back from the shoreline. In Louisiana that reality hasn't stepped in, so there’s still the hope that everything can be saved. So there's going to have to be some hard decisions in terms of where we abandon and where do we draw the line. But the bottom line is if you listen very carefully to the Corps of Engineers, they're no longer talking about “flood protection”, they talking about “risk reduction”.

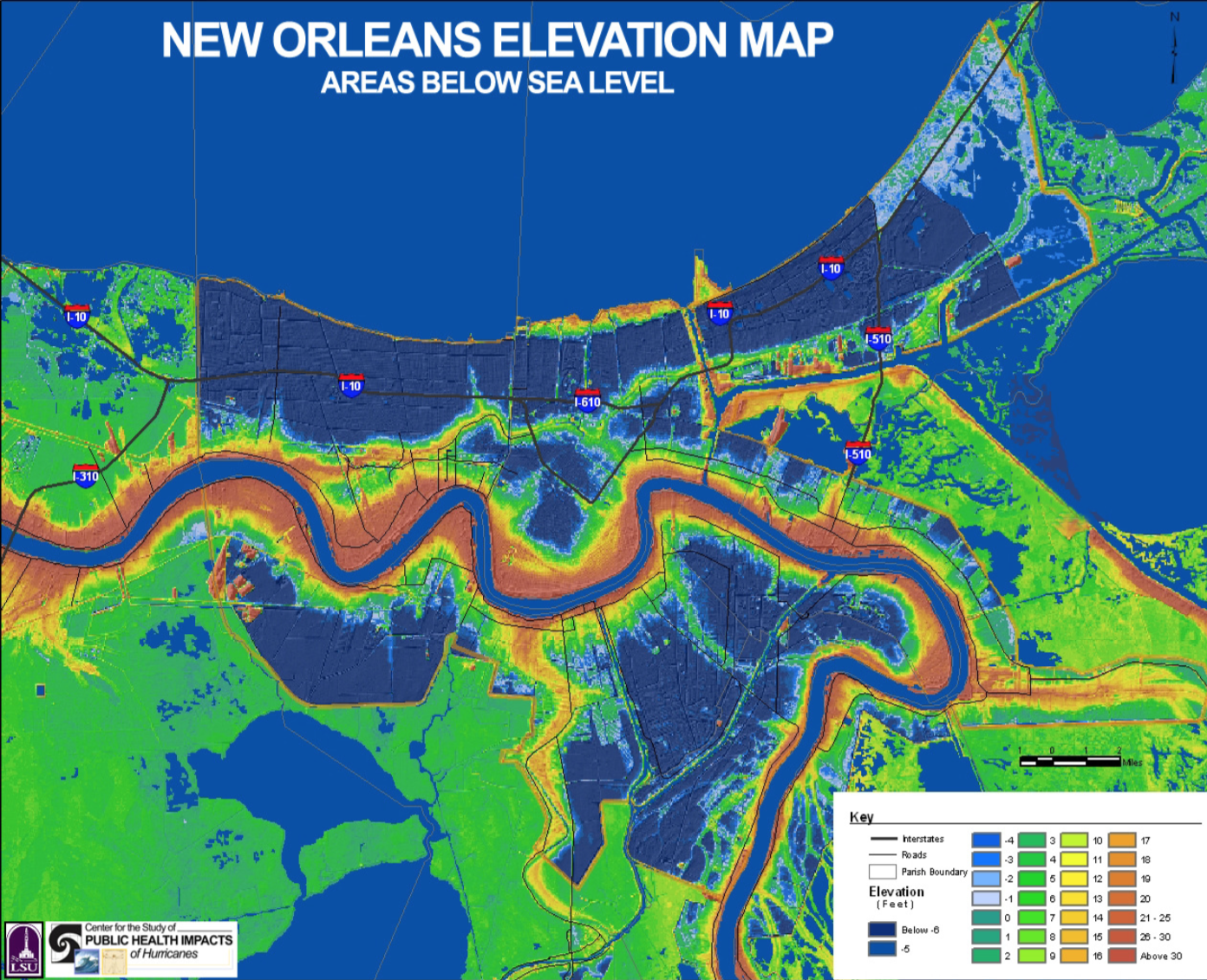

LIDAR mosaic is color-coded to show areas above sea level in brown, yellow and green, with areas below sea level as dark blue. About half of New Orleans lies below sea level, some areas by as much as six feet or more. (Photo: courtesy of Ivor van Heerden)

CURWOOD: Tell me about what the Army Corps of Engineers has done. I believe in 2012 they completed the rebuilding the existing levee system. What's the maximum type of storm that that system could withstand?

VAN HEERDEN: Well, yes, they've done the repairs, and the repairs are robust. The existing systems were strengthened with concrete pads in front, concrete pads in the back, so they should be able to withstand a certain amount of over-topping. And they've implemented a closure of the big navigation canal the MRGO, the Mississippi River gulf outlet, which is a project that many of us have called for for many number of years. The concern I have is that the Corps of Engineers is claiming that Katrina is a one in 400 year storm, and in reality the statistic should be that Katrina is a one in 30 year storm, and a storm that actually missed New Orleans. And if you go back to the last hundred years, there have been 4 or 5 storms that hit New Orleans and if we had something like Hurricane Betsy, which was a category four in 1965…in 1965, we still had lots and lots of wetlands. And if we had them today there could well be serious over-topping of the levee system.

A pendulum clock’s hands are frozen at 10:07. Realizing that the water would have stopped analog, digital and grandfather clocks as it filled homes, van Heerden organized the Stopped Clock Program. Data gathered from the program helped determine the approximate times at which homes had been flooded in each area. (Photo: courtesy of Ivor van Heerden)

CURWOOD: Ivor, to what extent does the public perception of the vulnerability of New Orleans today match up to the reality?

VAN HEERDEN: It's very interesting. I was at a function in the Lower Ninth Ward this past Saturday and these questions came up, and it was obvious that to me that most of the people in that room realized the importance of getting out of town the next time the storm comes and we discussed the appropriate behaviors: to make sure you got flood insurance on your home, and then pack all your valuables, grandma’s jewelry, whatever it is, in plastic boxes and when the storm comes get out of town...have a game plan. And it seemed to me that most of the people present had come up with the same decisions. So I think people are a lot more cautious now of what the Army Corps of Engineers is claiming and hopefully the next time this happens we will see even more people evacuating than did. Of course, the biggest thing is always the disabled and elderly. They are the ones who invariably cannot evacuate.

CURWOOD: Back in 2001, you were sounding the alarm about the vulnerability of the New Orleans region to a major storm surge, and then after Katrina you pointed to many of the flaws of what the Army Corps of Engineers and done and you wound up getting fired from your job at Louisiana State University. What's happened since then?

Despite being overtopped for about a mile and a half, this levee that protects the south side of St. Bernard parish suffered minimal damage. A marsh adjacent to it absorbed some of the impact from incoming waves. (Photo: courtesy of Ivor van Heerden)

VAN HEERDEN: I waited awhile. I waited almost a year to see if they would reconsider what they had done and they didn't, so I filed a lawsuit against them in federal court and then early in 2013 they contacted me at the 11th hour and offered a settlement. And so I felt we had won a major moral victory and that hopefully LSU wouldn't do that again. But the bottom line was I ended up being divorced from my science, from my students, access to supercomputers; and being damaged goods, I guess, I haven't really been able to find a job since. So my wife and I ended up taking early retirement. But I give many many talks, a lot, to high school students and what I point out to them is that when I shave in the morning I can look that guy in the eye and be quite happy with what he did.

CURWOOD: Now, Ivor, you lost your job for speaking truth to power, saying what was going on here. Did anyone else lose their jobs for failing to do the adequate job to protect New Orleans?

Since LSU terminated his contract in 2009, Ivor van Heerden has taken an early retirement. Van Heerden says he initially searched for another faculty position, without success. (Photo: courtesy of Ivor van Heerden)

VAN HEERDEN: No, nobody from the Corps of Engineers even got rapped over the knuckles and in fact some of them were given medals. I must point out that the LSU Hurricane Center, which was responsible for so much of the data production and the map production during the response no longer exists. So, not only did they do me a dirty, but they shut down one of the best things that existed at LSU.

CURWOOD: So what you're saying is that the state university system has no center devoted to analyzing what might happen if a hurricane comes again.

VAN HEERDEN: That's correct.

CURWOOD: Ivor van Heerden is a hurricane expert formerly at Louisiana State University Hurricane Center. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

VAN HEERDEN: Well, thank you very much.

Links

Living on Earth’s series on defending the Louisiana coast

From the archives: Our previous discussion with van Heerden

Katrina was a “crisis waiting to happen”

Katrina’s impact: data on deaths, displaced residents, damages, and recovery funding

Hurricane Katrina: The Essential Time Line

“Louisiana Is Falling off the Map”

“People’s hero, Corps’ villain or both? Investigator’s life upended by Katrina findings”

“The Man Who Predicted Katrina”: NOVA talks with Ivor van Heerden

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth