Racism and NOLA's Recovery

Air Date: Week of August 28, 2015

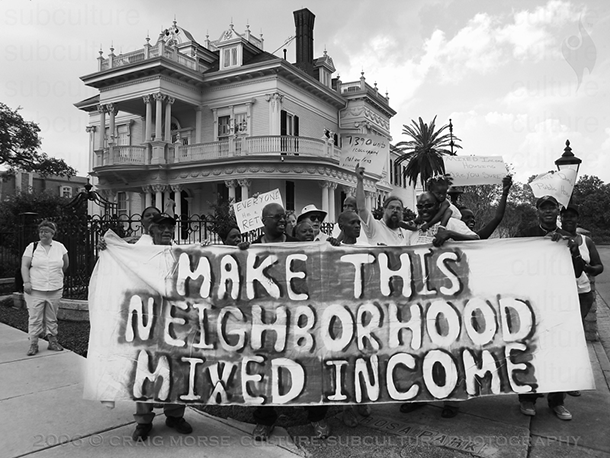

New Orleans residents protesting displacement in 2006 (Photo: Craig Morse, Culture:Subculture, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

New Orleans is celebrating a healthy recovery in places ten years after Katrina, but many black residents tell a different story. Prof. Beverly Wright of Dillard University and the Deep South Center on Environmental Justice says that the recovery has created opportunities for outside developers to pump money into the city and push black New Orleanians out.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Now, ten years after Katrina’s devastation, the levees have been repaired, but not the social fabric of New Orleans. While a recent study from the School of Mass Communications at Louisiana State University found that 78 percent of white residents felt the city was “mostly recovered” only 40 percent of black residents felt that way.

And here to explain the anger and disappointment of New Orleans’s community of color is Dillard University sociology professor, Beverly Wright, who also heads the Deep South Center on Environmental Justice. We last spoke on the five-year anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Professor Wright.

WRIGHT: Thank you, Steve, and it’s wonderful to be here.

CURWOOD: Remind us, please, just how long of you and your family lived in New Orleans?

WRIGHT: Well, my family has been here a very long time. We can trace our heritage back eight generations, slaves on one side and free coloreds on the other so we have been in New Orleans for a very, very long time.

CURWOOD: And what happened to your family during the aftermath of Katrina?

WRIGHT: Well what happened to our family is pretty typical of what happened to most African-American families, in that every family member lost everything except for one. We had one family member whose house did not go under because the house is perched on the Esplanade Ridge or what you call the “sliver on the river”, I understand that's a popular term for it now. So we only had one family member whose house did not go under.

CURWOOD: Last time we spoke I was in your recently rebuilt house in New Orleans East so how are you and your family and the black community doing 10 years on. Who has come back to the city?

WRIGHT: Well, a lot of people have come back. Those who could, the ones who still had jobs, most of my school teacher friends have not been able to come back in that the school board fired 7,500 school teachers which has had a devastating impact on the black middle class because you know that is one of our major occupations and it was one that we could count on for getting jobs, so I have friends now who aren't here, who are very unhappy that they are not here. So it's a long story, Steve, but the bottom line is that we are here, there are fewer of us than before. We are recovering, but we're not recovering at the same rate or quality as our white counterparts, and our biggest fear was that if certain things weren't put in place as related to recovery and equity, that we would see a seismic shift in the population in the city. I don't know if you remember that when I said that at our first conference that we needed to do things around equity and inclusion with the recovery in order for the African-American population to maintain its status and quality of life in the city.

Hurricane Katrina flooding in New Orleans (Photo: NOAA)

CURWOOD: Doesn't sound like that's happened, huh?

WRIGHT: It has not happened. In fact my worst fears are being realized in that the black middle class has taken an unbelievable hit. We're actually losing in income in the black middle class while the city is getting richer and whiter and more separate than what it was even before the storm. So we're watching gentrification occur at warp speed, we're watching inequities in the distribution of funds for the recovery, we're watching poor people who used to live in housing projects now being pushed out to Eastern New Orleans which is the bedrock of the middle-class black community.

CURWOOD: So who is moving in? In a recent op-ed you wrote about the rampant land grab that is displacing predominantly African-American families to the outskirts of the city? Who's moving in? Who are the outside developers here?

WRIGHT: Well, developers are responsible for the redrawing of the lines in terms of what kind of housing they're going to bring back, but it's mostly very... yuppies, young upwardly mobile white people whose intentions I would say overall are very good, but there's also a profit motive that's pulling them here and that is this new social entrepreneurship, in fact the city actually has an advertisement where a young white woman is saying, who would've thought that I could be a CEO at 27 years old where I opened my own company and I provide educational software to mostly the charter school networks that have created a cottage industry for young white people at the same time the children who are the product that this system are being bussed across the city at bus stops at 5:30 in the morning to go to schools not in their own neighborhood. So we see these kinds of things happening and children who really need services aren't getting them. We have charter schools networks making huge amounts of money, being given public property for quasi-private entities. And an unbelievable fight where mostly Teach for America teachers who are not trained as teachers and who I would never have allowed to teach my children are now teaching black children who no longer see themselves in public schools and their self-esteem is headed downward.

CURWOOD: This sounds like a nightmare.

WRIGHT: It's a nightmare for us. It's a paradise for some people, for newcomers to the city who are watching bike trails and, you know, I got to get suspicious when the Lafitte project was put online and they put soccer fields and not one basketball court in the green space, which told me they certainly were not expecting black children to return because our kid play basketball, not soccer. That's a good sign of who they were expecting to put in these spaces. They're literally whitewashing the city and, in fact, we have some zip codes that were 60, 70 percent black that are now 20 percent black and that's Faubourg, Marigny and that is the case for most of the zip codes that are in the city.

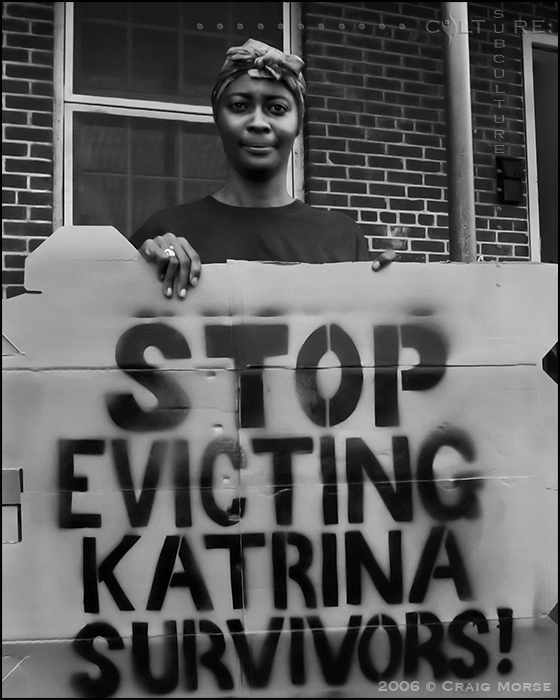

A protester from 2006, one year after the storm (Photo: Craig Morse, Culture:Subculture, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, Beverly, how does all this relate to environmental justice?

WRIGHT: Well, where you live, work and play is certainly an environmental issue and anytime you have in there some other real environmental directly related to the quality of the air and water and soil going on out here as well. We now even have public schools that are all being built on former waste sites with FEMA money. The largest municipal dump in the city up near the Magnolia projects and we've been fighting that and with the takeover of the schools we've lost our ability to control what happens in the RSD, that's the Recovery School District owned by the state has been moving forward with building a school for black children on that spot while there's another school Coyne High School which is three blocks in St. Charles which is coveted land, they're closing that school and moving those students to the school that's being built on a former toxic landfill. We're still not caring as much about the health of our children as we do white children, and we’re still making decisions that are dangerous for the health of the black community as compared to others. We have a big fight going on here and we're actually fighting for the soul of the city. If you look in the city where large numbers of white people are moving and they want noise ordinances now to be put in place in the French Quarter and then in the 6th ward where Louis Armstrong learned to play his horn on the front stoop, as we call it.

Beverly Wright at her home in New Orleans East (Photo: Steve Curwood)

WRIGHT: So, neighborhoods where you see young people practicing, blowing their horns on the street, and then walking into the French Quarter. The new people who would've moved into those neighborhoods only want Mardi Gras during Mardi Gras. They don't realize that it's a part of the culture that keeps Mardi Gras alive, so we're actually fighting for our soul here. That's what we're fighting for, and we're fighting to maintain our community and we're not moving, you know, because what generally happens is you just move. Well, we love where we live, we know that it's unique, and we're not moving. We're not moving, so we're staying and fighting, me and all of my neighbors.

CURWOOD: Beverly Wright heads the Deep South Center on Environmental Justice in New Orleans. Thanks so much, Professor Wright, for taking the time with us today.

WRIGHT: Well, thanks for listening. I'm always anxious to speak to people that I’m not certain want to hear what I have to say. [LAUGHS]

Links

Deep South Center for Environmental Justice

Dr. Beverly Wright’s op-ed on gentrification in New Orleans

Listen to a previous conversation between Steve and Dr. Wright

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth