Building a Sanctuary for Endangered Bats

Air Date: Week of October 30, 2015

Indiana bat (Photo: Adam Mann/USFWS)

Bats around the country are struggling to cope with the invasive European fungus White Nose syndrome. But writer Don Mitchell is trying to help by turning his farm into a sanctuary for the endangered bats that live on his property. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald reports from the Champlain Valley of Vermont.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Halloween sees the end of Bat Week – a nice fit for these spooky, and sometimes blood-sucking creatures. But in North America and Europe, these scary night-fliers eat huge amounts of harmful insects instead. North American bat numbers have plummeted in recent years though, due to a fungal disease called White Nose syndrome. So conservationists are doing all they can to help keep bats around. Don Mitchell is a writer and Vermont farmer whose memoir Flying Blind, documents his efforts to turn Treleven Farm into an endangered bat sanctuary. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald has the story.

FITZGERALD: Don Mitchell hasn’t always loved bats. Quite the opposite actually.

MITCHELL: I knew I disliked bats around 1975 when we found one in our bedroom flapping about our heads at night. And my instinctive reaction was one of fear.

Walking through the bat territories with Don Mitchell and Scott Darling (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: But one day, a man named Scott Darling from Fish and Wildlife showed up at Treleven Farm, and told Don that he had endangered Indiana bats living on the property. Don wasn’t particularly concerned about their wellbeing at first, but he saw an opportunity to lower his tax rate.

MITCHELL: I learned that I could create a forest management plan to put the farm into a tax abatement program, by foregrounding the fact that we had habitat for an endangered species.

FITZGERALD: Then he discovered that with a small amount of state funding he could actually enhance the habitat for bats, and increase his chances of getting the tax break.

MITCHELL: So my reasons for getting involved were entirely self-interested, selfish from the beginning. And I guess I became a believer.

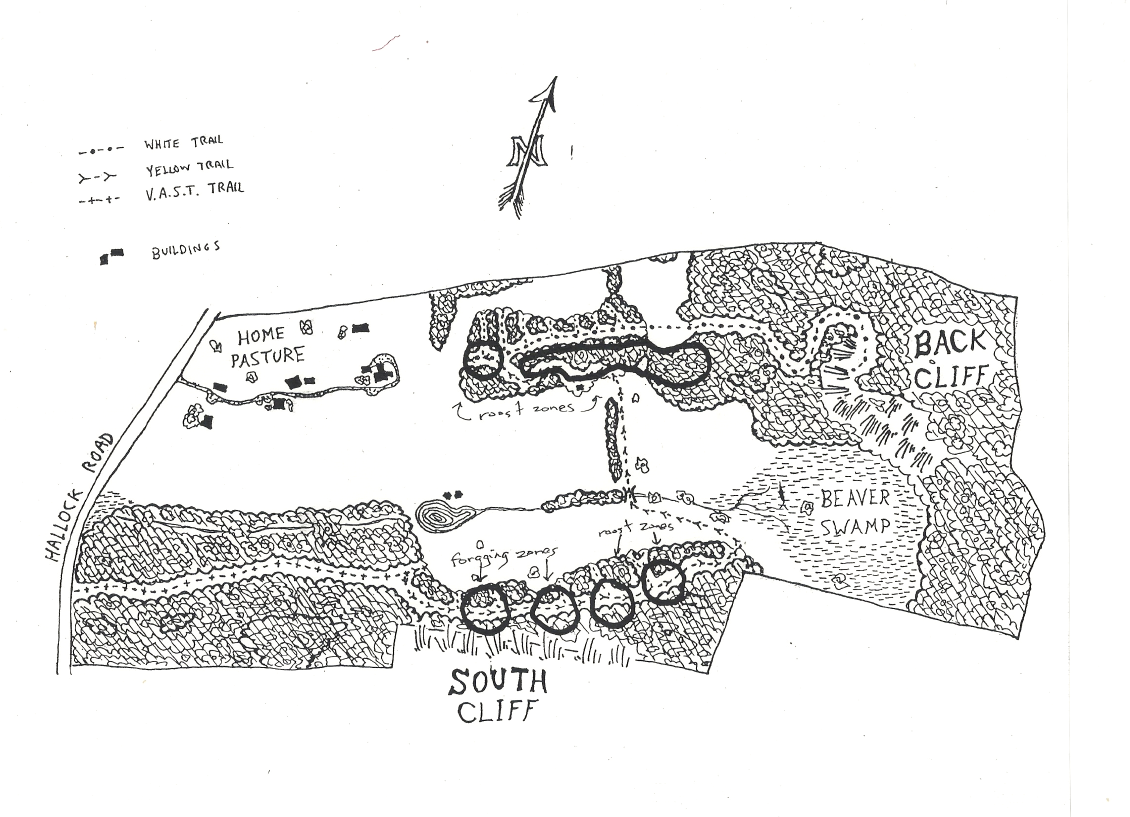

FITZGERALD: Don set about transforming five acres of field and forest on his farm in the Champlain Valley into sanctuary for Indiana bats. And Scott Darling gave him advice.

DARLING: We suggested to Don that he focus on roosting habitat, as well as try to provide some improved foraging habitat, so there would be areas where these bats could forage in somewhat of an open understory but still within a forest canopy.

Left to right: Don Mitchell’s daughter-in-law Susannah McCandless, Scott Darling, and Don Mitchell (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: It was an ambitious, sometimes backbreaking project, and Don is proud to show off his renovated bat territories to Scott and me.

[SOUNDS OF WALKING]

FITZGERALD: First we come to the roosting zone. Indiana bats are about two inches long and covered in chestnut colored fur. They usually sleep upside down in dead and dying trees, but Scott says that in Vermont they also like a species called the shagbark hickory.

DARLING: And they have these bark features, this almost peeling bark, that to an Indiana bat looks like a dead, and dying tree, and they can tuck themselves right under the bark and be very warm during the day, sleep protected from rain, and still be able to readily fly on out and forage at night.

FITZGERALD: Don had lots of shagbark hickories on the property, and as part of the management plan they submitted to the state, Scott recommended that he try to promote the growth of shagbarks in particular roosting zones. But to meet the state’s requirements, first Don had to eradicate all of the invasive species in the plot, plants like garlic mustard and buckthorn.

MITCHELL: These invasives they have the most amazing strategies, the garlic mustard will actually put what amounts to a poison in the soil that inhibits other plants from growing there, so it tends to colonize the forest floor. The buckthorn produces a seed, a berry that birds love to eat, and its cathartic so the birds get diarrhea when they eat it and poop out the seeds far and wide.

FITZGERALD: Clearing all these plants was a grueling process, but when Don had finished, the state gave him permission to “release” the shagbark hickories.

MITCHELL: To release them means to remove, to take down some of the forest canopy that surrounds them, to optimize their use by bats.

Shagbark hickories are great roosting habitats for endangered Indiana bats. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: Judging by Scott’s reaction today, Don did a pretty good job.

DARLING: Oh wow, I don’t know – yeah you know what the problem is, there’s too many to choose from now. Look at that! Some of these trees, their bark is a little different, see this one look at that piece, its like woahhhh you could put 20 bats in there!

FITZGERALD: So kind of the shaggier the better?

DARLING: Yeah the shaggier the better. Wowww that is beautiful.

FITZGERALD: Scott is excited to see good habitat like this. Bats in Vermont have been dying out en masse due to the invasive European fungal disease, White Nose syndrome.

DARLING: The hyphae from the fungus actually invade into the skin tissue, particularly near the wings, and begin to eat away at the tissue.

FITZGERALD: The fungus thrives in damp caves and mines where bats spend the winter, and began affecting hibernating bats about seven years ago.

DARLING: And eventually most of these bats would flee from the cave or mine, literally in the middle of January when no bat could survive outside, and they were dying across the landscape when White Nose syndrome first hit.

Scott and Don at the edge of the pond (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: White Nose was first discovered in a cave in New York in 2007. It showed up in Vermont in January of 2008.

DARLING: And what’s amazing is by 2010 we estimate we’d lost about 90 percent of our little brown bats and 90 percent of our Northern Long-eared bats, all in that two to three year window.

FITZGERALD: It’s a catastrophic decline. Since then Vermont’s Indiana and little brown bat populations have begun to stabilize, while long-eared bats continue to struggle with White-nose. Darling says the goal at this point is to keep the much-diminished bat populations afloat until either scientists can find a cure to white-nose, or the bats develop a natural resistance.

DARLING: We want to really minimize any other forms of mortality on our bat population, we know that they are being exposed to this disease. We’re really working to try to maintain again a good supply of dead and dying trees, good foraging habitat, good clean supplies of water, those are all going to be important in keeping that foundation of that population going. You know once you’ve lost it, there’s no going back.

FITZGERALD: Shall we keep walking?

[WALKING]

FITZGERALD: We cross through a meadow to a forest on the other side of the farm.

Entering the bat zones (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

MITCHELL: So now Scott can tell we’re entering the foraging zone. Which means that every tree less than seven inches in diameter at breast height was removed, to give the bats an easier time cruising around catching insects at night. We call this the all-night diner.

FITZGERALD: Bats tend to forage around the edge of the woods, which is dangerous because they’re exposed to predators like owls. But in here, they have enough room to cruise around and hunt for bugs under the safety of the forest canopy. This was Scott’s idea, but Don made it happen.

MITCHELL: Isn’t this beautiful. Oh my God, yeah. There’s so much more wildlife in here small birds and mammals and stuff.

DARLING: But here’s this case where these bats can forage in here really relatively easily, and still be under forest cover. This is really, from what we know about Indiana bats, from what I’ve observed about Indiana bats foraging, these are the conditions that are going to make it right.

FITZGERALD: Don says the key to this project is providing everything a bat needs in a relatively small amount of space.

Don Mitchell next to a shagbark hickory (Photo: Ethan Mitchell, Chelsea Green)

MITCHELL: Imagine for us if your home was in Middlebury and you had to go to Burlington to eat and you had to go to Montpelier for a drink of water, life would not be so simple. So trying to optimize habitat involves placing all the things that a creature needs in a reasonably constricted zone.

[WALKING]

FITZGERALD: As we walk back to the farmhouse Scott says he couldn’t be happier with how things are looking.

DARLING: We’ve actually increased habitat for a bat, and when you do that you increase its reproduction, its survival rates you do all these other things that affect populations positively.

FITZGERALD: Scott says it’s hard to be optimistic about the future of bats in the face of a disease as devastating as White Nose syndrome, but landowners like Don give him hope.

DARLING: People caring for the land and caring for a species of bats and making a difference. White Nose syndrome is the battle for bats, and this is one way that not just biologists but landowners can fight back as well.

FITZGERALD: Scientists still don’t know what the final impact of White-nose will be on the overall ecosystem. Bats are the primary nighttime predator for insects in Vermont, and losing 90% of them is bound to have ripple effects.

Hand-drawn map of the bat habitat (Photo: Don and Ethan Mitchell)

DARLING: My argument has always been that the wise person just doesn’t take away that one element, the bats there, and assume that everything will stay intact. So it’s just keeping all the pieces that’s really important. And this disease, this invasive disease, that has really affected one of those pieces, may well have implications we just know about.

FITZGERALD: Don Mitchell is doing his part to keep that piece around. He worked this land for decades without giving any thought to the bats that shared it with him. Then they became the focus of countless hours pulling buckthorn to make way for shagbark hickories. But he isn’t sure what the fruits of all that labor will be.

MITCHELL: One of the reasons the book is titled Flying Blind is because I think when we set out to tamper with the ecosystem for one narrowly defined goal or another, we often don’t have a keen sense of vision for what where we’re going or what we’re doing, and our goals change almost every generation, so we should do this with humility.

Flying Blind (Photo: Chelsea Green)

FITZGERALD: No matter what happens, Don says his opinion of bats has certainly changed. A few years ago he had the chance to hold a couple that Scott had trapped at night.

MITCHELL: They looked like a tiny Icarus, like a tiny little human being with wings. And I could look into their eyes and they could look into my eyes and some kind of transaction like ‘we’re both mammals here’ was taking place. I realized then that I had crossed some kind of a mental bridge, that now these were creatures that I cared about.

FITZGERALD: For Living on Earth, I’m Emmett FitzGerald in the Champlain Valley of Vermont.

CURWOOD: Don Mitchell’s memoir is called Flying Blind. There’s more at our website, LOE.org.

Links

Don Mitchell’s book Flying Blind from Chelsea Green

More about White Nose syndrome from the National Wildlife Health Center

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth