The Beekeepers of Ancient Egypt

Air Date: Week of November 13, 2015

Seal amulet, 2311-2140 BCE. Bone; 2.6 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of the John Huntington Art and Polytechnic Trust 1914.684.

Professor Gene Kritsky of Mount St Joseph’s University is an entomologist, but his latest book is a historical look at beekeeping in ancient Egypt. Professor Kritsky discusses honey, hives, and hieroglyphs with Living on Earth’s resident beekeeper Helen Palmer.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Well, bees and humans have interacted for millennia – new research shows beeswax in use some 8000 years ago in Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, and records of beekeeping in Egypt date back to the days of the Pharaohs. A new book called The Tears of Re documents what we know and how we know it – by the way “Re” is the name modern Egyptian scholars give the sun god who most of us grew up calling “Ra.” Gene Kritsky, chair of Biology Department at Mount St Joseph University in Cincinnati wrote the book, and he spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

PALMER: Professor Kritsky, your book is called, The Tears of Re. Can you read the inscription that gives it that title?

KRITSKY: Certainly, the title is inspired by a papyrus that was written around 300 BCE, and it tells the story of the god Re and the origin of bees and reads:

“The god Re wept, and the tears from his eyes fell on the ground and turned into a bee. The bee made his honeycomb and busied himself with the flowers of every plant and so wax was made and also honey out of the tears of Re.”

PALMER: So, tell me what the ancient Egyptians believed about bees?

A reconstruction of the beekeeping scene in the tomb of Rekhmire based on firsthand observations by Kritsky. (Photo: Gene Kritsky and used with permission.)

KRITSKY: Well, bees were considered sacred because they were a gift from Re. They were made from his tears and that gave bees not only a valuable aspect because of what they've contributed and brought to Egyptian society, but also they were theologically important. During the 26th dynasty, which is where the seat of the Egyptian government was at the time, in Sais the temple of Neith was called the house of the bee.

PALMER: The 26th dynasty...when about was that?

KRITSKY: That was approximately around 600 BCE.

PALMER: Now, they believed that the bees came from Re, but how important were they in Egyptian society?

.png)

The offering table with two containers of honey in the tomb of Menna. (Photo: Gene Kritsky and used with permission.)

KRITSKY: Bees were incredibly important in the sense of...the oldest honeybee hieroglyph goes back to just shy of 3000 BCE, so it was a very ancient symbol in the Egyptian writings, but even in the old kingdom beekeeping was an important activity organized by the state. We know that honey was important because it was an important sweetener to the Egyptian cuisine; it was also used as a medicine. And we know that beeswax was used in cosmetics as well as in paintings and even in some embalming practices.

PALMER: Well, we know, of course, that honey is a very powerful antiseptic now. I presume they didn't know of that value of it, but you say it was used as a medicine. Do we know how?

KRITSKY: Yes, it was. In fact, they would use honey for cuts and for burns. But of the 900 some odd prescriptions I found in some of the various medical papyri, close to 500 of them included honey as one of the ingredients. They used honey as a way of making the medicine taste a little sweeter, but it also, as you pointed out, had antibacterial properties, which also probably included medicinal value to the concoctions.

.png)

Beekeeping relief in the tomb of Pabasa. (Photo: Gene Kritsky and used with permission.)

PALMER: Of course, we're talking about a time when there wasn't sugar cane, there wasn't sugar beets. So there presumably wasn't any other main source of sweetener apart from honey and maybe fruit.

KRITSKY: That's correct. Indeed it was very expensive commodity in ancient Egypt and usually only the higher classes and parts of the Royal Court, for example, would have enjoyed honey.

PALMER: How do we know it was expensive?

KRITSKY: Well, we know that on a number of the papyri that talk about the rations given to workers.

We know that people who, for example, work directly with the Pharaoh would receive an allotment of honey daily, but the laborers did not.

PALMER: Is there any way of having an objective sort of like money value of it? Do we have any clue about that?

Part of a beekeeping relief at Pabasa’s tomb. (Photo: Gene Kritsky and used with permission.)

KRITSKY: Well, one of the things that's really, I think really interesting about ancient Egypt is that their economy was not currency-based like ours. Their entire economy is based on almost like a bartering economy. It was based on the concept of the deben, and that's a quantity of copper which could be used to make a certain-sized vessel. And they didn't carry around pieces of this copper. Instead if you're to be paid, let's say two bags of grain for a day’s work and the person paying you didn't have the grain, he or she could pay with an equivalent value of another commodity. It could be honey, it could be beer, it could be something like that. But they had a very complex understanding of the comparative value of various things that were needed for daily life.

PALMER: In your book you have some wonderful pictures of cave paintings and papyri that show honey. It was also used as a kind of tribute from the various provinces to the Pharaoh?

KRITSKY: Definitely. In the tomb of Rekmire, you'll find a whole series of paintings that show tribute being paid in the form of honey.

PALMER: So how much can we read about what the hieroglyphs tell us about bees?

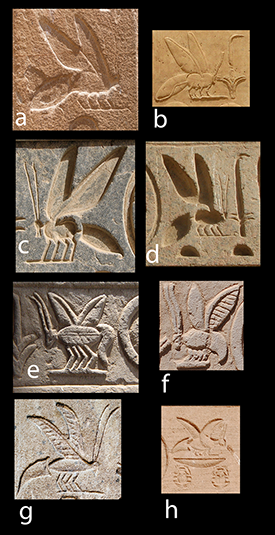

A honeybee hieroglyph throughout Egyptian history. a. Tomb of Mereruka, Sixth Dynasty; b. Deir el-Bahri, Eighteenth Dynasty; c. Ramesseum, Nineteenth Dynasty; d. Medinet Habu, Nineteenth Dynasty; e. Kom Ombo, Ptolemaic Period; f. Kom Ombo, Ptolemaic Period; g. Philae, Ptolemaic Period; h. Kalabsha Temple, Roman Era. (Photo: Gene Kritsky and used with permission.)

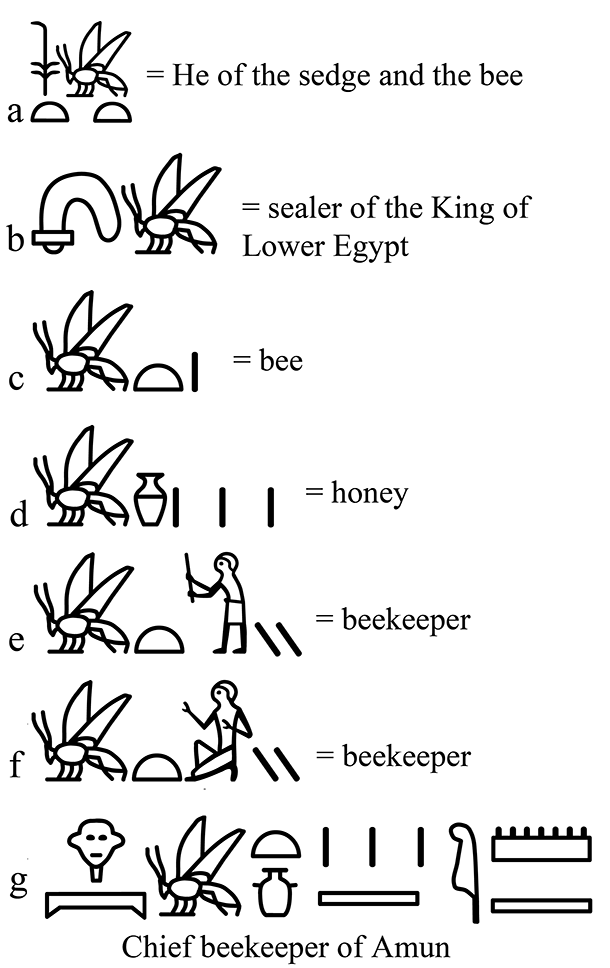

KRITSKY: Well, the Egyptian hieroglyph language was quite complex compared to ours. In addition having consonants like we have with our alphabet for example, they had over 700 hieroglyphic symbols, and the honeybee hieroglyph could represent with a certain notation to mean a bee, the actual insect, but it also formed the syllable bit. So if was part of the royal titular, which was Nesu-Biti, that would mean the King of Upper and Lower Egypt that represented the delta or Lower Egypt region of the country. It's also used in the word for honey, and it's also used in the word for beekeeper and symbolized, in the case of the word for beekeeper, you have a laborer next to a honeybee with the consonant for the t, that basely symbolized the occupation for the beekeeper.

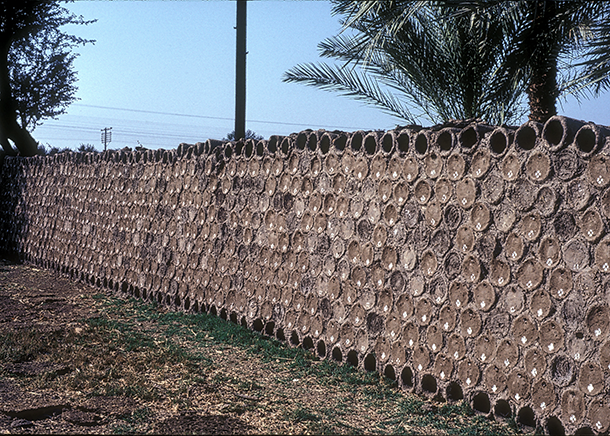

PALMER: Describe for me what the ancient Egyptian hives were like because they are quite different from the kind of hives we have today.

KRITSKY: Oh, they certainly were quite amazing. They were these horizontal tube hives. They were made out of mud that was dried into large cylinder and then stacked on top of each other, very similar in the construction of the hives we still see used in Azerbaijan and Iran, for example.

PALMER: Do we have any real understanding of exactly how they practiced beekeeping? Can you say to me if I were an Egyptian beekeeper what would I be doing on a daily basis or on a monthly basis?

KRITSKY: Well, we don't have any real evidence of how they actually kept their bees, but there are some practices that we can discern from the temple and tomb paintings. We know, of course, they used horizontal hives, but in one of the hives, the oldest one from 2450 BCE, we actually see the beekeeper holding something to his face and it's right up against the opening of the hive. The hieroglyph above it means “to weaken” or “to slacken” or “to emit a sound”, and that's been interpreted as smoking bees - which is a way of quieting bees - or may be calling bees. One of things the traditional Egyptian beekeepers practiced, they would call the queen, make a little sound and the queen would respond. That would tell them if there was a queen ready to emerge or what was the status inside the hive. If that was the case then their beekeeping was much more sophisticated than we can appreciate.

Egyptian words and phrases that incorporate the honey bee hieroglyph. (Photo: Gene Kritsky and used with permission.)

Once they got the honey, we have a painting that shows them removing round honeycomb from these horizontal hives. The honeycomb was crushed and then placed into containers. There's a sub-discipline called experimental archaeology. So of course I had to do this...I took honeycomb and I crushed it, and I put it in a container in hot sun and the beeswax floated the top and the honey stayed below the beeswax. And in one of the reliefs we actually see one of the beekeepers holding a vessel - it has a spout coming from not the top of the vessel but from the middle or towards the bottom - much like a gravy separator or a fat separator used for making gravy, and that may be one way they could've decanted a lot of the honey and not getting a lot of the wax mixed in with it. Once they had the honey separated from the wax, they would seal it in jars. In the Old Kingdom these jars were large and round. In the New Kingdom we see these sort of almost diamond shaped vessels that were like two bowls with the bottom bowl filled with honey and then a ring of wax along the middle and then another bowl on top and that was the typical container that was used to hold the honey.

PALMER: Now, you say they not only used the honey, they also made use of the wax. Tell me a bit more about how they used the wax.

KRITSKY: We know that wax was used in cosmetics, for example, they wore wigs and they would keep the curls of the wigs in place by using beeswax. We have evidence of beeswax being found in a very thin layer on some mummies, so it was used as a preservative that way but it wasn't going to be prevalent enough for the broader context. But beeswax was also important as a wonderful magical substance. Beeswax when it burns, it burns with a very bright light. It also doesn't leave any ash. Moreover, if you put beeswax in the hot Egyptian sun, it will start to change, it'll get a little molten like, a little liquidy. And so all these tied in with their solar theology would've been important to the Egyptians, and so they had a number of ways that you could take beeswax carvings, for example, if you wanted to ward off evil by taking a hippopotamus for example and carving it into an beeswax and igniting it and burning it away, that would be one kind of magic that would help form a protective spell, for example.

.png)

Four beeswax sons of Horus. From the left: Hapy, Duamutef, Imsety, and Imsety. Third Intermediate Period, late Twenty-first Dynasty (1069-945 BCE) or early Twenty-second Dynasty (945-715 BCE) (Photo: used with permission of the Cleveland Museum of Art)

PALMER: Wow, so you are, I know, a beekeeper yourself. Do you feel kinship with these ancient Egyptians and their beekeeping?

KRITSKY: Oh, I really do. There's something...if anybody out there has not kept bees or if they have kept bees they'll know what this like. Of course, western beekeeping, we're wearing the veil, the protective gear, and it sort of limits your peripheral vision. You've got your smoker going, and when you open up that hive and you smell the sweet smell of the honey and the honeycomb, and if when you're really at one with your bees you don't use gloves anymore. It's almost like a tai chi. You're carefully moving the frames around, so the bees don't get alarmed and don't sting you and so on. To me it's a very ancient occupation because it goes back to ancient Egypt obviously, but there's something that's kinship with us, humans and bees, that I find very alluring.

PALMER: Now so as far as we know, they didn't have some of the problems that beekeepers have today, and I know that you are actually working on bees and some of the problems in your current research. Can you tell me a little about that?

A wall apiary south of Minya in central Egypt. (Photo: Gene Kritsky and used with permission.)

KRITSKY: Certainly. I'm working in association with Dr. Andrew Rasmussen, he's our microbiologist here at Mount St. Joseph University, looking at the impact of fungicide contaminated beeswax foundation which is used to actually give the bees a little bit of a head start when they are starting a hive. So we're going out and we're seeing what flowers are the bees visiting. We're sampling those flowers for natural yeasts and fungi and we're intercepting the bees with their pollen balls as they're entering the beehive to get the pollen balls and then we're going into the hive itself to sample what the pollen is doing in the hive. The bee basically inoculates that pollen with yeasts which ferments the pollen into what we call bee bread - which is called bee bread because it actually smells like bread dough - and that fermentation that these yeasts do in the pollen helps convert it into the bee bread which the bees use as a food product.

Entomologist Gene Kritsky at Edfu (Photo: ©Jessee Smith, courtesy of Gene Kritsky)

PALMER: Typically when people are making new frames they put in a wax foundation, which is shaped like a honeycomb that tells bees where to actually build up walls. Are you saying that this foundation that all of us beekeepers buy and put into the hive is already contaminated with fungicide?

KRITSKY: Yes the recent papers have shown that close to if not all the foundation that's being manufactured now has fungicides already present in that wax and this may be a contributing factor to some of the bee health problems because the bees aren't getting the same nutrition they normally get if indeed natural yeasts are not present. And that's what we're trying to find out with our research. We're trying to see do these that yeast we're finding in the flowers, that we find in the pollen balls, how long are they still surviving in the honeycomb as the pollen is converted to bee bread.

PALMER: Wow, that's really interesting. I didn't know about the fungicides on the foundation.

KRITSKY: And it's not just fungicides. There's insecticides on some of the wax as well, so there are a number of laboratories around the states and in Europe that are looking at this question because it's rather critical because bees are important for life.

CURWOOD: That’s Gene Kritsky, Entomologist, Chair of the Biology Department at Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati and author of The Tears of Re. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer. And by the way, we asked what his current research on pesticides and fungicides in wax had discovered, and he told us “it’s still too soon.”

Links

The Tears of Re from Oxford University Press

Video: Kritsky on Advanced ancient Egyptian beekeeping techniques

Video: Kritsky on Medicinal uses of ancient Egyptian beekeeping

Video: Kritsky on the economic value of beekeeping

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth